Coleoptera: Carabidae, Trechinae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Species of Bembidion Latrielle 1802 from the Ozarks, with a Review

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 147: 261–275 (2011)A new species of Bembidion Latrielle 1802 from the Ozarks... 261 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.147.1872 RESEARCH ARTICLE www.zookeys.org Launched to accelerate biodiversity research A new species of Bembidion Latrielle 1802 from the Ozarks, with a review of the North American species of subgenus Trichoplataphus Netolitzky 1914 (Coleoptera, Carabidae, Bembidiini) Drew A. Hildebrandt1,†, David R. Maddison2,‡ 1 710 Laney Road, Clinton, MS 39056 USA 2 Department of Zoology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA † urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:038776CA-F70A-4744-96D6-B9B43FB56BB4 ‡ urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:075A5E9B-5581-457D-8D2F-0B5834CDE04D Corresponding author: David R. Maddison ([email protected]) Academic editor: T. Erwin | Received 31 July 2011 | Accepted 25 August 2011 | Published 16 November 2011 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:52038529-10EA-41A8-BE4F-6B495B610900 Citation: Hildebrandt DA, Maddison DR (2011) A new species of Bembidion Latrielle 1802 from the Ozarks, with a review of the North American species of subgenus Trichoplataphus Netolitzky 1914 (Coleoptera, Carabidae, Bembidiini). In: Erwin T (Ed) Proceedings of a symposium honoring the careers of Ross and Joyce Bell and their contributions to scientific work. Burlington, Vermont, 12–15 June 2010. ZooKeys 147: 261–275. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.147.1872 Abstract A new species of Bembidion (Trichoplataphus Netolitzky) from the Ozark Plateau of Missouri and Arkan- sas is described (Bembidion ozarkense Maddison and Hildebrandt). It is distinguishable from the closely related species, B. rolandi Fall, by characteristics of the male genitalia, and sequences of the genes cyto- chrome oxidase I and 28S ribosomal DNA. -

Coleoptera: Carabidae) by Thomas C

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Crossref TRECHOBLEMUS IN NORTH AMERICA, WITH A KEY TO NORTH AMERICAN GENERA OF TREX2HINAE (COLEOPTERA: CARABIDAE) BY THOMAS C. BARR, JR. The University of Kentucky, Lexington Trechoblemus Ganglbauer is a genus of trechine beetles (Tre- chinae: Trechini: Trechina) previously known only from Europe and Asia. It formed the type genus of Jeannel's "S6rie phyl6tique de Trechoblemus". and is generally regarded as closely related to cavernicolous trechines in Japan, the Carpathians and Transylvanian Alps of eastern Europe, and eastern United States (Barr, I969; Jeannel, I928, I962; U6no and Yoshida, I966). The large cave beetle genus Pseudanophthalmus Jeannel, with approximately 75 species in caves of ten eastern States, the monobasic genus Nea- phaenops Jeannel, from Kentucky caves, and the dibasic genus ]gelsonites Valentine, ]rorn Tennessee and Kentucky, are part of the Trechoblemus complex. The apparent restriction of Trechoblemus to Eurasia led previous investigators to conclude that, with respect to the richly diverse trechine fauna in caves of eastern United States, "there are no im- mediate, ancestral genera now present in North America" (Barr, 969, p. 83). Although there is at least one edaphobitic (obligate in soil) species of American Pseudanophthalmus known (P. sylvaticus Barr, I967), in the mountains of West Virginia, it has already lost eyes, wings, and pigment, and merely indicates that many of the "regressive" evolutionary changes in ancestral Pseudanohthal- mus may have taken place in the soil or deep humus before the beetles became restricted to caves. Most of the species of Pseuda- nophthalmus from eastern Europe (Barr, 964) are also eyeless edaphobites. -

Zootaxa,New Species of Anillinus Casey (Carabidae: Trechinae

Zootaxa 1542: 1–20 (2007) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2007 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) New species of Anillinus Casey (Carabidae: Trechinae: Bembidiini) from Great Smoky Mountains National Park, U.S.A. and phylogeography of the A. langdoni species group IGOR M. SOKOLOV1, YULIYA Y. SOKOLOVA2 & CHRISTOPHER E. CARLTON1 1Louisiana State Arthropod Museum, Department of Entomology, LSU Agricultural Center, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 70803, USA. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] 2Laboratory for Insect Pathology, Department of Entomology, LSU Agricultural Center, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 70803, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The Anillinus langdoni–species group is characterized and two new species are described, Anillinus cieglerae Sokolov and Carlton sp. nov. and A. pusillus Sokolov and Carlton sp. nov., both from Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The langdoni–group includes four species at present, three apparently endemic to the Great Smoky Mountains and adjacent mountains of western North Carolina/Tennessee, and a fourth from South Mountains of middle North Carolina. They are distinguished mainly using characters of the male genitalia and to a lesser extent, differences in shapes of female sper- mathecae. Phylogenetic analyses based on aedeagal morphology and COI gene sequences yielded conflicting results, with the later providing a phylogeny that was more parsimonious with expectations based on geographic distributions. Speciation within the group may derive from ecological constraints and altitudinal fluctuations of habitat corridors dur- ing past climate changes combined with the impact of local watersheds as fine scale isolating mechanisms. Key words: Coleoptera, Adephaga, Carabidae, Anillinus, South Appalachians, new species, taxonomy, identification key, COI gene sequences, phylogeography Introduction The genus Anillinus Casey is one of the most diverse genera of carabid beetles in the Southern Appalachian region of eastern United States. -

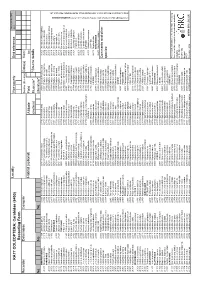

Carabidae Recording Card A4

Locality Grey cells for GPS RA77 COLEOPTERA: Carabidae (6453) Vice-county Grid reference users Recording Form Recorder Determiner Compiler Source (tick one) Date(s) from: Habitat (optional) Altitude Field to: (metres) Museum* *Source details No. No. No. Literature* OMOPHRONINAE 21309 Dyschirius politus 22335 Bembidion nigricorne 22717 Pterostichus niger 23716 Amara familiaris 24603 Stenolophus teutonus 25805 Dromius melanocephalus 20201 Omophron limbatum 21310 Dyschirius salinus 22336 Bembidion nigropiceum 22724 Pterostichus nigrita agg. 23717 Amara fulva 24501 Bradycellus caucasicus 25806 Dromius meridionalis CARABINAE 21311 Dyschirius thoracicus 22338 Bembidion normannum 22718 Pterostichus nigrita s.s. 23718 Amara fusca 24502 Bradycellus csikii 25807 Dromius notatus 20501 Calosoma inquisitor 21401 Clivina collaris 22339 Bembidion obliquum 22723 Pterostichus rhaeticus 23719 Amara infima 24503 Bradycellus distinctus 25808 Dromius quadrimaculatus 20502 Calosoma sycophanta 21402 Clivina fossor 22340 Bembidion obtusum 22719 Pterostichus oblongopunctatus 23720 Amara lucida 24504 Bradycellus harpalinus 25810 Dromius quadrisignatus 20401 Carabus arvensis BROSCINAE 22341 Bembidion octomaculatum 22703 Pterostichus quadrifoveolatus 23721 Amara lunicollis 24505 Bradycellus ruficollis 25811 Dromius sigma 20402 Carabus auratus 21501 Broscus cephalotes 22342 Bembidion pallidipenne 22720 Pterostichus strenuus 23722 Amara montivaga 24506 Bradycellus sharpi 25809 Dromius spilotus 20404 Carabus clathratus 21601 Miscodera arctica 22343 Bembidion prasinum -

Coleoptera: Carabidae) Peter W

30 THE GREAT LAKES ENTOMOLOGIST Vol. 42, Nos. 1 & 2 An Annotated Checklist of Wisconsin Ground Beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae) Peter W. Messer1 Abstract A survey of Carabidae in the state of Wisconsin, U.S.A. yielded 87 species new to the state and incorporated 34 species previously reported from the state but that were not included in an earlier catalogue, bringing the total number of species to 489 in an annotated checklist. Collection data are provided in full for the 87 species new to Wisconsin but are limited to county occurrences for 187 rare species previously known in the state. Recent changes in nomenclature pertinent to the Wisconsin fauna are cited. ____________________ The Carabidae, commonly known as ‘ground beetles’, with 34, 275 described species worldwide is one of the three most species-rich families of extant beetles (Lorenz 2005). Ground beetles are often chosen for study because they are abun- dant in most terrestrial habitats, diverse, taxonomically well known, serve as sensitive bioindicators of habitat change, easy to capture, and morphologically pleasing to the collector. North America north of Mexico accounts for 2635 species which were listed with their geographic distributions (states and provinces) in the catalogue by Bousquet and Larochelle (1993). In Table 4 of the latter refer- ence, the state of Wisconsin was associated with 374 ground beetle species. That is more than the surrounding states of Iowa (327) and Minnesota (323), but less than states of Illinois (452) and Michigan (466). The total count for Minnesota was subsequently increased to 433 species (Gandhi et al. 2005). Wisconsin county distributions are known for 15 species of tiger beetles (subfamily Cicindelinae) (Brust 2003) with collection records documented for Tetracha virginica (Grimek 2009). -

Vol 4 Part 2. Coleoptera. Carabidae

Royal Entomological Society HANDBOOKS FOR THE IDENTIFICATION OF BRITISH INSECTS To purchase current handbooks and to download out-of-print parts visit: http://www.royensoc.co.uk/publications/index.htm This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. Copyright © Royal Entomological Society 2012 ROYAL ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON . Vol. IV. Part 2 -HANDBOOKS FOR THE IDENTIFICATION / OF BRITISH INSECT-s COLEOPTERA CARABIDAE By CARL H. LINDROTH LONDON Published by the Society and Sold at its Rooms .p, Queen's Gate, S.W. 7 August I 974- HANDBOOKS FOR THE IDENTIFICATION OF BRITISH INSECTS The aim of this series of publications is to provide illustrated keys to the whole of the British Insects (in so far as this is possible), in ten volumes, as follows: I. Part 1. General Introduction. Part 9. Ephemeroptera. , 2. Thysanura. , 10. Odonata. , 3. Protura. , 11. Thysanoptera. , 4. Collembola. , 12. Neuroptera. , 5. Dermaptera and , 13. Mecoptera. Orthoptera. , 14. Trichoptera. , 6. Plecoptera. , 15. Strepsiptera. , 7. Psocoptera. , 16. Siphonaptera. , 8. Anoplura. II. Hemiptera. III. Lepidoptera. IV. and V. Coleoptera. VI. Hymenoptera : Symphyta and Aculeata. VII. Hymenoptera : lchneumonoidea. VIII. Hymenoptera : Cynipoidea, Chalcidoidea, and Serphoidea. IX. Diptera: Nematocera and Brachycera. X. Diptera : Cyclorrhapha. Volumes II to X will be divided into parts of convenient size, but it is not possible to specifyin advance the taxonomic content of each part. Conciseness and cheapness are main objectives in this series, and each part is the work of a specialist, or of a group of specialists. Although much of the work is based on existing published keys, suitably adapted, much new and original matter is also included. -

Carabidae (Coleoptera) and Other Arthropods Collected in Pitfall Traps in Iowa Cornfields, Fencerows and Prairies Kenneth Lloyd Esau Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1968 Carabidae (Coleoptera) and other arthropods collected in pitfall traps in Iowa cornfields, fencerows and prairies Kenneth Lloyd Esau Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Esau, Kenneth Lloyd, "Carabidae (Coleoptera) and other arthropods collected in pitfall traps in Iowa cornfields, fencerows and prairies " (1968). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 3734. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/3734 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 69-4232 ESAU, Kenneth Lloyd, 1934- CARABIDAE (COLEOPTERA) AND OTHER ARTHROPODS COLLECTED IN PITFALL TRAPS IN IOWA CORNFIELDS, FENCEROWS, AND PRAIRIES. Iowa State University, Ph.D., 1968 Entomology University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan CARABIDAE (COLEOPTERA) AND OTHER ARTHROPODS COLLECTED IN PITFALL TRAPS IN IOWA CORNFIELDS, PENCEROWS, AND PRAIRIES by Kenneth Lloyd Esau A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Pkrtial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY -

Morphological and Micromorphological Description of the Larvae of Two Endemic Species of Duvalius (Coleoptera, Carabidae, Trechini)

biology Article Morphological and Micromorphological Description of the Larvae of Two Endemic Species of Duvalius (Coleoptera, Carabidae, Trechini) Cristian Sitar 1,2,* , Lucian Barbu-Tudoran 3,4 and Oana Teodora Moldovan 1,5,* 1 Romanian Institute of Science and Technology, Saturn 24-26, 400504 Cluj-Napoca, Romania 2 Zoological Museum, Babes, Bolyai University, Clinicilor 5, 400006 Cluj-Napoca, Romania 3 Faculty of Biology and Geology, Babes, Bolyai University, Clinicilor 5, 400006 Cluj-Napoca, Romania; [email protected] 4 INCDTIM Cluj-Napoca, Str. Donath 67-103, 400293 Cluj-Napoca, Romania 5 Department of Cluj, Emil Racovita Institute of Speleology, Clinicilor 5, 400006 Cluj-Napoca, Romania * Correspondence: [email protected] (C.S.); [email protected] (O.T.M.) Simple Summary: The Duvalius cave beetles have a wide distribution in the Palearctic region. They have distinct adaptations to life in soil and subterranean habitats. Our present study intends to extend the knowledge on the morphology of cave Carabidae by describing two larvae belonging to different species of Duvalius and the ultrastructural details with possible implications in taxonomy and ecology. These two species are endemic for limited areas in the northern and north-western Romanian Carpathians. Our study provides knowledge on the biology and ecology of the narrow endemic cave beetles and their larvae are important in conservation and to establish management measures. Endemic species are vulnerable to extinction and, at the same time, an important target of Citation: Sitar, C.; Barbu-Tudoran, L.; global conservation efforts. Moldovan, O.T. Morphological and Micromorphological Description of Abstract: The morphological and ultrastructural descriptions of the larvae of two cave species of the Larvae of Two Endemic Species of Trechini—Duvalius (Hungarotrechus) subterraneus (L. -

A New Genus and Species of Troglobitic Trechinae (Coleoptera, Carabidae) from Southern China

Int. J. Speleol., 25,1-2 (1996): 33-41. 1997 A new genus and species of troglobitic Trechinae (Coleoptera, Carabidae) from southern China Augusto Vigna Taglianti * SUMMARY Guizhaphaenops zorzini n.gen.n.sp. is described from Anjia Yan Cave, Shuicheng County, Guizhou (China). This highly specialized troglobite species is easily recognizable from the other cave dwelling Trechini from China for the main morphological external characters, but its true re- lationships remain uncertain, the male being still unknown. Similar in habitus to Cathaiaphaenops and to Sinotroglodytes. the new taxon is much more related to the latter, being dorsally glabrous and having the mentum fused with the submentum, with a deep oval fovea, but it differs in its elongated head, with incomplete frontal furrows and without posterior frontal setae. Only few years ago an extraordinary new genus and species, Sinaphaenops mirabilissimus Ueno & Wang, 1991, was discovered in Guizhou (Libo County), in Southeast China; it was the first record of an anophthalmic trechine beetle from mainland China (Ueno & Wang, 1991). None of the eyeless trechine spe- cies, quite abundant in the temperate zones, especially in Northern Hemisphere and also in Eastern Asia, with many genera and species described from Taiwan, Korea and especially Japan (see also Vigna Taglianti & Casale, 1996), was pre- viously known from China. Another new genus and species, Dongodytes fowleri Deuve, 1993, was described two years later from Guangxi, collected by an ex- pedition organized by Chinese and British speleologists. Recently, in a paper by Deuve (1996), three other anophthalmic cave- dwelling trechines were described from Northwest Hunan, collected in the karst of Longshan in August 1995, by French and Chinese speleologists of the expe- dition "Xiangxi 95"; they were ascribed to two new genera (Cathaiaphaenops and Sinotroglodytes) and to one new subgenus (Cimmeritodes) of the Japanese genus Gotoblemus Deno, 1970. -

Zootaxa, an Updated Checklist of the Ground Beetles

Zootaxa 2318: 169–196 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) An updated checklist of the ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae) of Sardinia* AUGUSTO VIGNA TAGLIANTI Dipartimento di Biologia Animale e dell’Uomo, Sapienza Università di Roma, Viale dell’Università 32, I-00185 Rome, Italy. E-mail: [email protected] *In: Cerretti, P., Mason, F., Minelli, A., Nardi, G. & Whitmore, D. (Eds), Research on the Terrestrial Arthropods of Sardinia (Italy). Zootaxa, 2318, 1–602. Abstract An up-to-date checklist of the ground beetles of Sardinia and surrounding islets is presented. The presence on the island of 379 species is confirmed, while 41 are here considered of doubtful occurrence. All endemic elements are indicated and concise information is given on the Italian distribution of each species, together with the chorotype of recurrent pattern of main distribution. Key words: Carabidae, checklist, distribution, chorotypes, endemics, Sardinia, Italian fauna Introduction The first list of the ground beetles of Sardinia was published as an appendix in a paper by Casale and Vigna Taglianti (1996). Such list, with 351 species, was the result of the critical examination of all bibliographical data on Sardinia and especially of the material collected by Italian entomologists during more than thirty years of research trips in mainland Sardinia and its surrounding small islands and archipelagos. The nomenclature and taxonomy of that list followed the “Checklist delle specie della fauna italiana” (Vigna Taglianti 1993), the first attempt to update the list of Italian carabids after Magistretti’s (1965) catalogue. -

New and Interesting Records of Carabid Beetles from South-East

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Linzer biol. Beitr. 43/1 501-547 25.7.2011 New and interesting records of Carabid Beetles from South-East Europe, South-West and Central Asia, with taxonomic notes on Pterostichini and Zabrini (Coleoptera, Carabidae) B. GUÉORGUIEV A b s t r a c t : New combinations and new synonyms are proposed: Pterostichus (Cryobius) carradei (GAUTIER DES COTTES 1866), comb.nov. of Feronia carradei GAUTIER DES COTTES 1866; Feronia insidiosa FAIRMAIRE 1866, syn.nov. of Feronia carradei GAUTIER DES COTTES 1866; Pterostichus serbicus APFELBECK 1899, syn.nov. of Pterostichus (Feronidius) incommodus SCHAUM 1858; Feronia similata GAUTIER DES COTTES 1870, syn.nov. of Pterostichus (Pseudomaseus) fuscicornis (REICHE & SAULCY 1855); Amara (Leiocnemis) ochracea (CAUTIER DES COTTES 1868), comb.nov. of Feronia ochracea GAUTIER DES COTTES 1868; Amara abnormis TSCHITSCHERINE 1894, syn.nov. of Feronia ochracea GAUTIER DES COTTES 1868. Lectotypes for Feronia carradei, F. insidiosa, and F. similata are designated. Species recorded for the first time for the following countries: Bosnia Herzegovina: Nebria psammodes (P. ROSSI); N. diaphana ssp. relicta (BREIT); Notiophilus interstitialis REITTER; Cychrus schmidti CHAUDOIR; Clivina laevifrons CHAUDOIR; Reicheiodes rotundipennis ssp. rotundipennis (CHAUDOIR); Scarites laevigatus FABRICIUS; Bembidion azurescens ssp. azurescens DALLA TORRE; B. quadricolle (MOTSCHULSKY); B. femoratum ssp. femoratum STURM ; B. incognitum J. MÜLLER; B. schueppelii DEJEAN; Sinechostictus doderoi (GANGLBAUER); Tachyura walkeriana ssp. walkeriana (SHARP); Pogonistes rufoaeneus (DEJEAN); Blemus discus ssp. discus (FABRICIUS); Trechus secalis ssp. secalis (PAYKULL); Harpalus hospes ssp. hospes STURM; Ophonus similis (DEJEAN); Parophonus hirsutulus (DEJEAN); Dromius fenestratus (FABRICIUS); Badister lacertosus STURM; Atranus ruficollis (GAUTIER DES COTTES); Pedius longicollis (DUFTSCHMID); Polystichus connexus (GEOFFROY). -

Conservation Assessment for Marengo Cave Ground Beetle (Pseudanophthalmus Stricticollis)

Conservation Assessment for Marengo Cave Ground Beetle (Pseudanophthalmus Stricticollis) (Barr, 1960) USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region October 2002 Julian J. Lewis, Ph.D. J. Lewis & Associates, Biological Consulting 217 W. Carter Avenue Clarksville, IN 47129 [email protected] This Conservation Assessment was prepared to compile the published and unpublished information on Pseudanophthalmus stricticollis. It does not represent a management decision by the U.S. Forest Service. Though the best scientific information available was used and subject experts were consulted in preparation of this document, it is expected that new information will arise. In the spirit of continuous learning and adaptive management, if you have information that will assist in conserving the subject community and associated taxa, please contact the Eastern Region of the Forest Service Threatened and Endangered Species Program at 310 Wisconsin Avenue, Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53203. Conservation Assessment for Marengo Cave Ground Beetle (Pseudanophthalmus Stricticollis) 2 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................... 4 NOMENCLATURE AND TAXONOMY .................................................. 4 DESCRIPTION OF SPECIES .................................................................... 5 LIFE HISTORY............................................................................................ 5 HABITAT .....................................................................................................