An Empirical Analysis of Land Reforms in West Bengal, India'1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supermarkets in India: Struggles Over the Organization of Agricultural Markets and Food Supply Chains

\\jciprod01\productn\M\MIA\68-1\MIA109.txt unknown Seq: 1 12-NOV-13 14:58 Supermarkets in India: Struggles over the Organization of Agricultural Markets and Food Supply Chains AMY J. COHEN* This article analyzes the conflicts and distributional effects of efforts to restructure food supply chains in India. Specifically, it examines how large retail corporations are presently attempting to transform how fresh produce is produced and distributed in the “new” India—and efforts by policymakers, farmers, and traders to resist these changes. It explores these conflicts in West Bengal, a state that has been especially hostile to supermarket chains. Via an ethnographic study of small pro- ducers, traders, corporate leaders, and policymakers in the state, the article illustrates what food systems, and the legal and extralegal rules that govern them, reveal about the organization of markets and the increasingly large-scale concentration of private capital taking place in India and elsewhere in the developing world. INTRODUCTION .............................................................. 20 R I. ON THE RISE OF SUPERMARKETS IN THE WEST ............................ 24 R II. INDIA AND THE GLOBAL SPREAD OF SUPERMARKETS ....................... 29 R III. LAND, LAW, AND AGRICULTURAL MARKETS IN WEST BENGAL .............. 40 R A. Land Reform, Finance Capital, and Agricultural Marketing Law ........ 40 R B. Siliguri Regulated Market ......................................... 47 R C. Kolay Market ................................................... 53 R D. -

Journal of Bengali Studies

ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Vol. 6 No. 1 The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 1 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426), Vol. 6 No. 1 Published on the Occasion of Dolpurnima, 16 Phalgun 1424 The Theme of this issue is The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century 2 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Volume 6 Number 1 Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 Spring Issue The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Editorial Board: Tamal Dasgupta (Editor-in-Chief) Amit Shankar Saha (Editor) Mousumi Biswas Dasgupta (Editor) Sayantan Thakur (Editor) 3 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Copyrights © Individual Contributors, while the Journal of Bengali Studies holds the publishing right for re-publishing the contents of the journal in future in any format, as per our terms and conditions and submission guidelines. Editorial©Tamal Dasgupta. Cover design©Tamal Dasgupta. Further, Journal of Bengali Studies is an open access, free for all e-journal and we promise to go by an Open Access Policy for readers, students, researchers and organizations as long as it remains for non-commercial purpose. However, any act of reproduction or redistribution (in any format) of this journal, or any part thereof, for commercial purpose and/or paid subscription must accompany prior written permission from the Editor, Journal of Bengali Studies. -

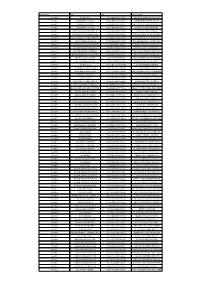

We Refer to Reserve Bank of India's Circular Dated June 6, 2012

We refer to Reserve Bank of India’s circular dated June 6, 2012 reference RBI/2011-12/591 DBOD.No.Leg.BC.108/09.07.005/2011-12. As per these guidelines banks are required to display the list of unclaimed deposits/inoperative accounts which are inactive / inoperative for ten years or more on their respective websites. This is with a view of enabling the public to search the list of accounts by name of: Cardholder Name Address Ahmed Siddiq NO 47 2ND CROSS,DA COSTA LAYOUT,COOKE TOWN,BANGALORE,560084 Vijay Ramchandran CITIBANK NA,1ST FLOOR,PLOT C-61, BANDRA KURLA,COMPLEX,MUMBAI IND,400050 Dilip Singh GRASIM INDUSTRIES LTD,VIKRAM ISPAT,SALAV,PO REVDANDA,RAIGAD IND,402202 Rashmi Kathpalia Bechtel India Pvt Ltd,244 245,Knowledge Park,Udyog Vihar Phase IV,Gurgaon IND,122015 Rajeev Bhandari Bechtel India Pvt Ltd,244 245,Knowledge Park,Udyog Vihar Phase IV,Gurgaon IND,122015 Aditya Tandon LUCENT TECH HINDUSTAN LTD,G-47, KIRTI NAGAR,NEW DELHI IND,110015 Rajan D Gupta PRICE WATERHOUSE & CO,3RD FLOOR GANDHARVA,MAHAVIDYALAYA 212,DEEN DAYAL UPADHYAY MARG,NEW DELHI IND,110002 Dheeraj Mohan Modawel Bechtel India Pvt Ltd,244 245,Knowledge Park,Udyog Vihar Phase IV,Gurgaon IND,122015 C R Narayan CITIBANK N A,CITIGROUP CENTER 4 TH FL,DEALING ROOM BANDRA KURLA,COMPLEX BANDRA EAST,MUMBAI IND,400051 Bhavin Mody 601 / 604, B - WING,PARK SIDE - 2, RAHEJA,ESTATE, KULUPWADI,BORIVALI - EAST,MUMBAI IND,400066 Amitava Ghosh NO-45-C/1-G,MOORE AVENUE,NEAR REGENT PARK P S,CALCUTTA,700040 Pratap P CITIBANK N A,NO 2 GRND FLR,CLUB HOUSE ROAD,CHENNAI IND,600002 Anand Krishnamurthy -

Income Distribution, Market Imperfections and Capital Accumulation in a Developing Economy

Income Distribution, Market Imperfections and Capital Accumulation in a Developing Economy Asim K. Dasgupta Foreword by Amartya Sen Income Distribution, Market Imperfections and Capital Accumulation in a Developing Economy “I find this book very interesting. Prior to Asim Dasgupta’s work, the standard growth and development models ignored credit constraints and their implications for resource allocations and growth. This had disturbing implications: a redistribu- tion of income from the rich to the poor would lower savings and investment, thus capital accumulation and growth. But redistributions in a credit constrained world may lead to a more efficient allocation of capital, thereby improving growth. While the findings are intuitive,Income Distribution, Market Imperfections and Capital Accumulation in a Developing Economy presents a simple and convincing model to establish them with some rigor. The exposition is sufficiently clear that it should be easy to follow.” —Joseph E. Stiglitz, American economist and Professor at Columbia University, USA. He is also a recipient of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (2001) and the John Bates Clark Medal (1979). Asim K. Dasgupta Income Distribution, Market Imperfections and Capital Accumulation in a Developing Economy Asim K. Dasgupta Former Finance Minister West Bengal, India Former Professor of Economics Calcutta University West Bengal, India ISBN 978-981-13-1632-6 ISBN 978-981-13-1633-3 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1633-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018953330 -

GST-SME Sector

© 2018 JETIR October 2018, Volume 5, Issue 10 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) GST – The Game Changer for Indian Economy: GST-SME sector Naaharavaar Lakshmishree Dharmendra –Research scholar Dr Gaurav Khanna- Research Guide Madhav University, Abu road , Sirohi , Rajasthan Abstract: In this paper my aim is to study about GST, journey of GST, foreign countries who have adopted GST model , impact of GST on SME sector . Indian government has structured GST for efficient tax collection, reduction in corruption, easy inter-state movement of goods, Make in India promotion etc. because of all these factor Indian SME will be more competitive in international market which will compete with China, Bangladesh etc .New emerging market in FMCG ,textile, ecommerce ,automobile sector will be benefited in future Main issue in GST is tax evasion arising out of small businesses not registering, under- reporting of actual sales by traders; traders collecting tax but not remitting to the government; and traders making false claims for refunds. Finally I just want to suggest that government should focus on cyber security ,strong IT infrastructure ,GST learning programmes for local people then and only we will get long term benefit. Keyword : SME, foreign countries ,tax evasion , cyber security ,IT infrastructure ,Learning programmes Introduction of GST In India, GST is proposed to have a dual structure— a Central GST levied and collected by the Centre and a state GST administered by States. The Goods and Service Tax will bring into place a unified taxation system, which would merge most of the existing taxes into a single taxation system. -

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 01600009 GHOSH JAYA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 01600009 GHOSH JAYA U72200WB2005PTC104166 ANI INFOGEN PRIVATE LIMITED 01600031 KISHORE RAJ YADAV U24230BR1991PTC004567 RENHART HEALTH PRODUCTS 01600031 KISHORE RAJ YADAV U00800BR1996PTC007074 ZINNA CAPITAL & SAVING PRIVATE 01600031 KISHORE RAJ YADAV U00365BR1996PTC007166 RAWATI COMMUNICATIONS 01600058 ARORA KEWAL KUMAR RITESH U80301MH2008PTC188483 YUKTI TUTORIALS PRIVATE 01600063 KARAMSHI NATVARLAL PATEL U24299GJ1966PTC001427 GUJARAT PHENOLIC SYNTHETICS 01600094 BUTY PRAFULLA SHREEKRISHNA U91110MH1951NPL010250 MAHARAJ BAG CLUB LIMITED 01600095 MANJU MEHTA PRAKASH U72900MH2000PTC129585 POLYESTER INDIA.COM PRIVATE 01600118 CHANDRASHEKAR SOMASHEKAR U55100KA2007PTC044687 COORG HOSPITALITIES PRIVATE 01600119 JAIN NIRMALKUMAR RIKHRAJ U00269PN2006PTC022256 MAHALAXMI TEX-CLOTHING 01600119 JAIN NIRMALKUMAR RIKHRAJ U29299PN2007PTC130995 INNOVATIVE PRECITECH PRIVATE 01600126 DEEPCHAND MEHTA VALCHAND U52393MH2007PTC169677 DEEPSONS JEWELLERS PRIVATE 01600133 KESARA MANILAL PATEL U24299GJ1966PTC001427 GUJARAT PHENOLIC SYNTHETICS 01600141 JAIN REKHRAJ SHIVRAJ U00269PN2006PTC022256 MAHALAXMI TEX-CLOTHING 01600144 SUNITA TULI U65993DL1991PLC042580 TULI INVESTMENT LIMITED 01600152 KHANNA KUMAR SHYAM U65993DL1991PLC042580 TULI INVESTMENT LIMITED 01600158 MOHAMED AFZAL FAYAZ U51494TN2005PTC056219 FIDA FILAMENTS PRIVATE LIMITED 01600160 CHANDER RAMESH TULI U65993DL1991PLC042580 TULI INVESTMENT LIMITED 01600169 JUNEJA KAMIA U32109DL1999PTC099997 JUNEJA SALES PRIVATE LIMITED 01600182 NARAYANLAL SARDA SHARAD U00269PN2006PTC022256 -

Sustainable Innovation on Business & Commerce

National Seminar on SUSTAINABLE INNGVATIGNS ^BUSINESS AND COMMERCE % Seminar Proceeding & Book of Papers Department of Commerce ./ii^iffiliQle'dlfp^Jgcigypu Kolkat^Z00020 BGeseb 03352:4533251-3 i3=fMT7f[h w.TiiWiriithrniiggntfflTrfrTrfhxJfa o m N'alional Seminar on SUSTAINABLE INniOVATIONS girgRl /" BUSINESS AI\ID COn/in/IEBCE National Seminar on SUSTAINABLE INNOVATIONS 'BUSINESS AND COMMERCE 19'" & 20" April, 2018 J. D. BIRLA INSTITUTE Department of Commerce (Affiliated to Jadavpur University) 11 Lower Rawdon Street, Kolkata-700020 Phone: 033-24755070,033-2476340; Telefox: 033-24543243 EmaU: [email protected], Website: wwwjdbikolkata.in Compiled bv Dr. Manodip Ray Chaudhuri Mrs. Monalika Dey Edited by Dr. Shweta Tuteja Ms. Yamini Dhanania Cop5night @ 2018 JDBI All rights reserved Address J. D. Birla Institute 11, Lower Rawdon Street, Kolkata - 700020 (West Bengal), India First Published April, 2018 Price m Cover Designed by Sanjib Adak Graphic Designer, JDBI Printed by CDC Printers (P) Ltd.. Tangra Industrial Estate-ll, 45. Radhanath Chowdhury Road, Koikata-TOOOIS (WB). India Published bv: J.D. Biria Institute, Kolkata (West Bengal), India National Seminar on SUSTAIWABIE IIIIWOVATIOWS EBUSINESS AI\ID COMMERCE About J.D. BIRLA INSTITUTE J.D. Biria Inscinite, Kolkata, is a leading educational inscitucion in Kolkata is affiliated to Jadavpur University, a university of distinction and one of the ' finest in the country. In fact, it is the only college affiliated to this prestigious univenity.The instinite has also been accredited with an'A' grade by NAAC in 2010, and is currently preparing forits tliird cycle ;."^y several rating agencies. The Instinite completed its Golden Jubilee in 2013 and currentlyhas about ISOOstudents. -

View Full Profile

CURRICULUM VITAÉ Shirsendu Roychowdhury 33 Natunpally, Barisha, Silpara, Kolkata 700008 Phones: (Res) (033) 24454656, (Mob) 8017107650 Email: [email protected] Objective To serve your esteemed institution with my knowledge and skills and also enhance my knowledge base and abilities. Academic Passed MSc (Economics) Examination in 2007 from the University of Calcutta Qualifications with 60% marks (1st Class). My Special Paper was “International Economics” and my Optional Paper was “Development Management” Passed BSc (Economics Honors) Examination in 2005 from the University of Calcutta and secured 52% marks. Field Experience: During my BSc course I participated in a survey conducted at Darjeeling by the Department of Economics, Vivekananda College, May 2003 Passed Higher Secondary Examinations under WBCHSE in 2002 from Vivekananda College and was placed in 1st Division with 61% marks. Passed ICSE Examinations in 2000 with 83.4% marks from Vivekananda Mission School. Has qualified the West Bengal State Eligibility Test for lectureship (SET- equivalent to NET) in 2008. Awards and achievements Work Experience Working as an Assistant Professor of Economics in the Commerce Department (Morning) and BBA Department Of St. Xavier’s College (autonomous), Kolkata since July 2015. Worked as an Assistant Professor in St.Xavier’s College in UGC FDP post for one and a half years in Commerce Morning Department from Nov 2013 to May 2015. Worked as a Guest Lecturer in BBA Department of St.Xavier’s College from July 2011 to May 2015 and as a part time lecturer in Commerce (Morning) Department of St.Xavier’s College from January 2010 to Nov.2013. Worked as a Part-time Lecturer of Economics in Lady Brabourne College from October 2009 to June 2014.; Worked as a Guest Lecturer in Vivekananda College from September 2012 for two years. -

Uttarbanga Unnayan Parshad

Annual Report 2009-10 The Development & Planning Department is responsible for the formulation of the State’s Annual Plans and the Five year Plans in collaboration with the different Departments of the Government and in consonance with the guidelines of the Planning Commission of India. The Department also facilitates the preparation of the District Plans by the District Planning Committees. With the help of other Departments and District Authorities this Department monitors the implementation of the District Plans, Annual Plans, & the Five Year Plans. The Development & Planning Department finalises any matter involving policy which concerns more than one Department but not included in the Rule of Business of any other Department. The Development & Planning Department takes the responsibility of looking into all matter relating to the constitution and functioning of the State Planning Board, District Planning Committees and Uttarbanga Unnayan Parshad. The Department is the controlling authority of the Bureau of Applied Economics & Statistics. A “Human Development Resource Coordination Centre” had been set up under the Department as a way forward to focus on Human Development issues in the planning process. The project “Strengthening State Plan for Human Development had been initiated since 2005 and it gets its fund from Planning Commission of India and United Nations Development Programme. The Development & Planning Department is the Nodal Department for monitoring of the implementation of the Government of India programmes - ‘Member of Parliament Local Area Development Scheme’, the ‘Twenty Point Programme-2006’ and Public Private Partnership (PPP) Projects. The Department also implements and monitors schemes of Bidhayak Elaka Unnayan Prakalpa and Natural Resource Data Management System. -

Land Reform and Farm Productivity in West Bengal By

LAND REFORM AND FARM PRODUCTIVITY IN WEST BENGAL1 Pranab Bardhan2 and Dilip Mookherjee3 This version: April 23, 2007 Abstract We revisit the classical question of productivity implications of sharecropping tenancy, in the context of tenancy reforms (Operation Barga) in West Bengal, India studied previously by Banerjee, Gertler and Ghatak (JPE 2002). We utilize a disaggregated farm panel, controlling for other land reforms, agriculture input supply services, infrastructure spending of local governments, and potential endogeneity of land reform implementation. We continue to find significant positive effects of lagged village tenancy registration rates. But the direct effects on tenant farms are overshadowed by spillover effects on non-tenant farms. The effects of tenancy reform are also dominated by those of input supply programs and irrigation expenditures of local governments. These results indicate the effects of the tenancy reform cannot be interpreted as reduction of Marshall-Mill sharecropping distortions alone; village-wide impacts of land reforms and agricultural input supply programs administered by local governments deserve greater attention. 1For research support we are grateful to the MacArthur Foundation Inequality Network and the National Science Foundation (Grant No. SES-0418434). Monica Parra Torrado and Neha provided outstanding re- search assistance. We thank officials of the West Bengal government who granted access to the data; to Sankar Bhaumik and Sukanta Bhattacharya of the Department of Economics, Calcutta University who led the village survey teams; to Bhaswar Moitra and Biswajeet Chatterjee of the Department of Economics, Ja- davpur University who led the teams that collected the farm data; to Indrajit Mallick and Sandip Mitra who helped us collect other relevant data. -

History, Ideology and Negotiation the Politics of Policy Transition in West Bengal, India

The London School of Economics and Political Science History, Ideology and Negotiation The Politics of Policy Transition in West Bengal, India Ritanjan Das A thesis submitted to the Department of International Development of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy London January 2013 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 101100 words. I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Sue Redgrave. ii For Baba iii Abstract The thesis offers an examination of a distinct chapter in the era of economic reforms in India - the case of the state of West Bengal - and narrates the politics of an economic policy transition spearheaded by the Left Front coalition government that ruled the state from 1977 to 2011. In 1991, the Government of India began to pursue a far more liberal policy of economic development, with emphasis being placed on non-agricultural growth, the role of the private sector, and the merits of foreign direct investment (FDI). -

Goods and Services Tax (India)

Best Personal Counseling & Guidance about SSB Contact - R S Rathore @ 9001262627 visit us - www.targetssbinterview.com Goods and Services Tax (India) Goods and Services Tax (GST) is an indirect tax applicable throughout India which replaced multiple cascading taxes levied by the central and state governments. It was introduced as The Constitution (One Hundred and First Amendment) Act 2017, following the passage of Constitution 122nd Amendment Bill. The GST is governed by a GST Council and its Chairman is the Finance Minister of India. Under GST, goods and services are taxed at the following rates, 0%, 5%, 12% and 18%. There is a special rate of 0.25% on rough precious and semi-precious stones and 3% on gold. In addition a cess of 15% or other rates on top of 28% GST applies on few items like aerated drinks, luxury cars and tobacco products. Touted by the government to be India's biggest tax reform in 70 years of independence, the Goods and Services Tax (GST) was finally launched on the midnight of 30 June 2017, though the process of forming the legislation took 17 years (since 2000 when it was first proposed). The launch was marked by a historic midnight (30 June - 1 July 2017) session of both the houses of parliament convened at the Central Hall of the Parliament. The reform process of India's indirect tax regime was started in 1986 by Vishwanath Pratap Singh with the introduction of the Modified Value Added Tax (MODVAT). A single common "Goods and Services tax (GST)" was proposed and given a go-ahead in 1999 during a meeting between then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee and his economic advisory panel, which included three former RBI governors IG Patel, Bimal Jalan and C Rangarajan.