Roleplaying Games in the Digital Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAY 19Th 2018

5z May 19th We love you, Archivist! MAY 19th 2018 Attention PDF authors and publishers: Da Archive runs on your tolerance. If you want your product removed from this list, just tell us and it will not be included. This is a compilation of pdf share threads since 2015 and the rpg generals threads. Some things are from even earlier, like Lotsastuff’s collection. Thanks Lotsastuff, your pdf was inspirational. And all the Awesome Pioneer Dudes who built the foundations. Many of their names are still in the Big Collections A THOUSAND THANK YOUS to the Anon Brigade, who do all the digging, loading, and posting. Especially those elite commandos, the Nametag Legionaires, who selflessly achieve the improbable. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – The New Big Dog on the Block is Da Curated Archive. It probably has what you are looking for, so you might want to look there first. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – Don't think of this as a library index, think of it as Portobello Road in London, filled with bookstores and little street market booths and you have to talk to each shopkeeper. It has been cleaned up some, labeled poorly, and shuffled about a little to perhaps be more useful. There are links to ~16,000 pdfs. Don't be intimidated, some are duplicates. Go get a coffee and browse. Some links are encoded without a hyperlink to restrict spiderbot activity. You will have to complete the link. Sorry for the inconvenience. Others are encoded but have a working hyperlink underneath. Some are Spoonerisms or even written backwards, Enjoy! ss, @SS or $$ is Send Spaace, m3g@ is Megaa, <d0t> is a period or dot as in dot com, etc. -

MARCH 1St 2018

March 1st We love you, Archivist! MARCH 1st 2018 Attention PDF authors and publishers: Da Archive runs on your tolerance. If you want your product removed from this list, just tell us and it will not be included. This is a compilation of pdf share threads since 2015 and the rpg generals threads. Some things are from even earlier, like Lotsastuff’s collection. Thanks Lotsastuff, your pdf was inspirational. And all the Awesome Pioneer Dudes who built the foundations. Many of their names are still in the Big Collections A THOUSAND THANK YOUS to the Anon Brigade, who do all the digging, loading, and posting. Especially those elite commandos, the Nametag Legionaires, who selflessly achieve the improbable. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – The New Big Dog on the Block is Da Curated Archive. It probably has what you are looking for, so you might want to look there first. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – Don't think of this as a library index, think of it as Portobello Road in London, filled with bookstores and little street market booths and you have to talk to each shopkeeper. It has been cleaned up some, labeled poorly, and shuffled about a little to perhaps be more useful. There are links to ~16,000 pdfs. Don't be intimidated, some are duplicates. Go get a coffee and browse. Some links are encoded without a hyperlink to restrict spiderbot activity. You will have to complete the link. Sorry for the inconvenience. Others are encoded but have a working hyperlink underneath. Some are Spoonerisms or even written backwards, Enjoy! ss, @SS or $$ is Send Spaace, m3g@ is Megaa, <d0t> is a period or dot as in dot com, etc. -

A Player's Guide to Tabletop Role-Playing Games in Libraries

Western University Scholarship@Western FIMS Publications Information & Media Studies (FIMS) Faculty 2019 Roll for Initiative: A Player’s Guide to Tabletop Role-Playing Games in Libraries Carlie Forsythe University of Western Ontario, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/fimspub Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Citation of this paper: Forsythe, Carlie, "Roll for Initiative: A Player’s Guide to Tabletop Role-Playing Games in Libraries" (2019). FIMS Publications. 343. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/fimspub/343 Running head: ROLL FOR INITIATIVE: A PLAYER’S GUIDE TO TTRPGS IN LIBRARIES 1 Roll for Initiative: A Player’s Guide to Tabletop Role-Playing Games in Libraries Submitted by Carlie Forsythe Supervised by Dr. Heather Hill LIS 9410: Independent Study Submitted: August 9, 2019 Updated: February 4, 2020 ROLL FOR INITIATIVE: A PLAYER’S GUIDE TO TTRPGS IN LIBRARIES 2 INTRODUCTION GM: You see a creepy subterranean creature hanging onto the side of a pillar. It is peering at you with one large, green eye. What do you do? Ranger: I’m going to drink this invisibility potion and cross this bridge to get a closer look. I’m also going to nock an arrow and hold my attack in case it notices me. Cleric: One large green eye. Where have I seen this before? Wait, I think that’s a Nothic. Bard Can I try talking to it? GM: Sure, make a persuasion check. Bard: I rolled a 7, plus my modifier is a 3, so a 10. What does that do? GM: The Nothic notices you and you can feel its gaze penetrating your soul. -

The 2016 Dungeons & Dragons Dungeon Master

SLY FLOURISH’S OF RETURN THE LAZY DUNGEON MASTER BY MICHAEL E. SHEA APPENDICES THE 2016 DUNGEONS & DRAGONS DUNGEON MASTER SURVEY Tis book makes frequent references to the 2016 Dungeons & Dragons Dungeon Master survey, LENGTH OF GAMES • About an hour: 1% conducted at the Sly Flourish website between October 28 and November 28, 2016. Tis appendix • About two hours: 5% contains a summary of the results of that survey. You • About three hours: 28% can fnd the full results, along with the raw data, at • About four hours: 44% http://slyfourish.com/2016_dm_survey_results.html. • About six hours: 17% Survey respondents came from multiple online • About eight hours: 4% D&D communities, including the Dungeons & Dragons Google Plus community, the Reddit D&D Next community, the ENWorld forum for D&D, the PREPARATION TIME • None: 2% Facebook D&D community, and on Twitter. Tere were a total of 6,600 responses. Te results below • About 15 minutes: 4% have all been rounded to the nearest percent. • About 30 minutes: 10% Here are the summarized results relating to games • About an hour: 23% and game preparation. • About two hours: 24% • About three hours: 14% FREQUENCY OF GAMES • About four hours: 8% • More than twice weekly: 2% • More than four hours: 14% • Twice a week: 6% • Weekly: 43% OTHER RESULTS • Twice monthly: 26% In addition to providing a strong sense of the • Monthly: 13% relationship between play and prep time for GMs, the • Less than Monthly: 10% survey covered a wide range of other information. 88 Primary Game Play Locations Combat Encounters -

Mutants and Masterminds Character Sheet Fillable Pdf

Mutants and masterminds character sheet fillable pdf Sorry, folks, my pure fu is weak. Has anyone created an editable .pdf for DCA/M'M3? If so, could you point this poor soul in the right direction? I know about the character of the Hero Lab sheet, but the money is being tough (but it looks so good...). Thank you in advance. Oh, editable sheet of characters. I thought you said it wasn't a list of characters. I would get that in an instant. Carry on. There's one on the MLM/DCA forums here. Scroll down a bit at the Resources Forum - this one is on skis. I haven't tried his/her 3e version yet, but I found a second ed. Excel sheet is very useful and quite easy to use. If 3e one as well, I highly recommend it. Thank you. I'll check it out. Sorry, folks, my pure fu is weak. Has anyone created an editable .pdf for DCA/M'M3? If so, could you point this poor soul in the right direction? I know about the character of the Hero Lab sheet, but the money is being tough (but it looks so good...). Thank you in advance. Don't add any disappointment, but Hero Lab also allows you to keep the character as a PDF. I believe that the flow of 3E resources someone associated with you also has some other sheets of PDF characters, but I'm not sure any of them are editable. Oh, editable sheet of characters. I thought you said it wasn't a list of characters. -

Popular Franchises As Tabletop Rpgs Rev. 6 (Nov. 2020)

Popular Franchises as Tabletop RPGs Rev. 6 (Nov. 2020) Ctrl+F to find your way around. Use capitalization if nothing is coming up. Franchise Free? Game Name Website .hack// ✓ Infinite Generation http://dothack.info/index.php?title=Category%3 A.hack%2F%2FInfinite_Generation A Certain ✓ A Certain Roleplaying https://1d4chan.org/wiki/A_Certain_Role- Scientific Game playing_Game Railgun Ace Attorney ✓ Abjection! https://www.reddit.com/r/AceAttorney/commen ts/8zwgwa/abjection_a_little_rpg_game_inspired _by_ace ✓ Cookie Jar https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/115517/ Cookie-Jar https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/84260/S $12 Skullduggery kulduggery Adventure ✓ Adventure Time 4E www.mediafire.com/?ia9628cdx6zacwb + Time http://www.mediafire.com/file/kmxkml5mzduc9 94/AdventureTimeBeta_PrintFriendly.pdf/file “Though I’m not releasing a new version just for this, people reading this original post should note that hit points should be initially calculated using your constitution SCORE, not your constitution MODIFIER.” FarUniverse https://faruniverse.com/ ✓ https://docs.google.com/file/d/0BwNr37N7Yp6b ✓ Tabletop Adventure Time cDRmMnZSZ0V3a2s/edit - List of homebrews & https://www.reddit.com/r/rpg/comments/81nf9g/any_chance_of_a n_english_adventure_time_rpg/ + https://mutant- history future.fandom.com/wiki/Adventure_Time Age of ✓ Gods and Monsters https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/150889/ Mythology (Fate) Akira $10 KISHU (PbtA) https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/319947/ See also Battle KISHU Angel: Alita. $11 Cybergeneration (CP2020) https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/25143/ ✓ Psychedemia (Fate) https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/142732/ Aladdin $50 City of Brass (5E) https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/266871/ Prince of City-of-Brass-5e Often goes on sale for significantly less. Persia, The $25 City of Brass (SW/OSR) https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/266876/ Etc. -

Universidade Federal Do Rio Grande Do Sul Instituto De Informática Curso De Ciência Da Computação

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL INSTITUTO DE INFORMÁTICA CURSO DE CIÊNCIA DA COMPUTAÇÃO HENRIQUE LUIZ TELLES DA SILVA PRASS Análise de Jogos de RPG em Mesas Virtuais Monografia apresentada como requisito parcial para a obtenção do grau de Bacharel em Ciência da Computação. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Raul Fernando Weber Porto Alegre 2017 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL Reitor: Prof. Rui Vicente Oppermann Vice-Reitora: Prof.ª Jane Fraga Tutikian Pró-Reitor de Graduação: Prof. Vladimir Pinheiro do Nascimento Diretora do Instituto de Informática: Prof.ª Carla Maria Dal Sasso Freitas Coordenador do Curso de Ciência da Computação: Prof. Raul Fernando Weber Bibliotecária-Chefe do Instituto de Informática: Beatriz Regina Bastos Haro AGRADECIMENTOS Gostaria de agradecer ao meu orientador Prof. Dr. Raul Weber pelo apoio e encorajamento para a realização deste trabalho. Também gostaria de agradecer à minha família pelo apoio constante em todos os aspectos, em especial ao meu irmão Bernardo. RESUMO Os jogos de RPG de Mesa são uma forma de entretenimento que pode ser considerada bastante complexa. Através do uso de aplicativos de Mesas Virtuais é possível analisar vários aspectos relacionados às simplificações adotadas pelos formatos eletrônicos de RPG. O tema central deste trabalho é a investigação e avaliação das diversas características e métodos utilizados em Mesas Virtuais para representar os elementos e processos de um RPG de Mesa. A proposta do trabalho é a definição das características que estariam presentes em uma Mesa Virtual Ideal, que representaria a fusão dos melhores aspectos dos RPGs de Mesa e RPGs Eletrônicos. Palavras-chave: Jogos, RPG, Mesas Virtuais, Jogos Eletrônicos, Análise de Jogos. -

Uncovering Seams in Distributed Play of Tabletop Role-Playing Games

Uncovering Seams in Distributed Play of Tabletop Role-Playing Games Andrew M. Webb Pablo Cesar Abstract CWI CWI We uncover how geographically distributed players of table- Amsterdam, Netherlands Delft University of Technology top role-playing games engage narrative, ludic, and social [email protected] Amsterdam, Netherlands aspects of play. Our existing understandings of tabletop [email protected] role-playing games are centered around co-located play on physical tabletops. Yet, online play is increasingly popular. We interviewed 14 players, experienced with online virtual tabletops. Our findings reveal the seams—points where media, activities, and technology intersect—within virtual tabletop environments that enable distributed players to shift among collaborative storytelling, applying game rules and mechanics, and socially interacting with each other. CCS Concepts •Human-centered computing ! Ethnographic studies; Author Keywords Dungeons & Dragons; narrativity; virtual tabletop; Roll20 Introduction Permission to make digital or hard copies of part or all of this work for personal or Tabletop role-playing games, such as Dungeons & Drag- classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation ons, are seeing a resurgence in popular culture [2]. In these on the first page. Copyrights for third-party components of this work must be honored. games, players take on the roles of fictional characters as For all other uses, contact the Owner/Author. they collaboratively create stories while sitting around a CHI PLAY EA ’19, October 22–25, 2019, Barcelona, Spain. table. Players interact with various physical objects, such © 2019 Copyright is held by the owner/author(s). -

Uncovering Seams in Distributed Play of Tabletop Role-Playing Games

Uncovering Seams in Distributed Play of Tabletop Role-Playing Games Andrew M. Webb Pablo Cesar Abstract CWI CWI We uncover how geographically distributed players of table- Amsterdam, Netherlands Delft University of Technology top role-playing games engage narrative, ludic, and social [email protected] Amsterdam, Netherlands aspects of play. Our existing understandings of tabletop [email protected] role-playing games are centered around co-located play on physical tabletops. Yet, online play is increasingly popular. We interviewed 14 players, experienced with online virtual tabletops. Our findings reveal the seams—points where media, activities, and technology intersect—within virtual tabletop environments that enable distributed players to shift among collaborative storytelling, applying game rules and mechanics, and socially interacting with each other. CCS Concepts •Human-centered computing ! Ethnographic studies; Author Keywords Dungeons & Dragons; narrativity; virtual tabletop; Roll20 Introduction Permission to make digital or hard copies of part or all of this work for personal or Tabletop role-playing games, such as Dungeons & Drag- classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation ons, are seeing a resurgence in popular culture [2]. In these on the first page. Copyrights for third-party components of this work must be honored. games, players take on the roles of fictional characters as For all other uses, contact the Owner/Author. they collaboratively create stories while sitting around a CHI PLAY EA ’19, October 22–25, 2019, Barcelona, Spain. table. Players interact with various physical objects, such © 2019 Copyright is held by the owner/author(s). -

Dungeons & Dragons

5z May 30th We love you, Archivist! MAY 30th 2018 Attention PDF authors and publishers: Da Archive runs on your tolerance. If you want your product removed from this list, just tell us and it will not be included. This is a compilation of pdf share threads since 2015 and the rpg generals threads. Some things are from even earlier, like Lotsastuff’s collection. Thanks Lotsastuff, your pdf was inspirational. And all the Awesome Pioneer Dudes who built the foundations. Many of their names are still in the Big Collections A THOUSAND THANK YOUS to the Anon Brigade, who do all the digging, loading, and posting. Especially those elite commandos, the Nametag Legionaires, who selflessly achieve the improbable. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – The New Big Dog on the Block is Da Curated Archive. It probably has what you are looking for, so you might want to look there first. - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - – - - - - - - - - - - - - - - – - - - - - – Don't think of this as a library index, think of it as Portobello Road in London, filled with bookstores and little street market booths and you have to talk to each shopkeeper. It has been cleaned up some, labeled poorly, and shuffled about a little to perhaps be more useful. There are links to ~16,000 pdfs. Don't be intimidated, some are duplicates. Go get a coffee and browse. Some links are encoded without a hyperlink to restrict spiderbot activity. You will have to complete the link. Sorry for the inconvenience. Others are encoded but have a working hyperlink underneath. Some are Spoonerisms or even written backwards, Enjoy! ss, @SS or $$ is Send Spaace, m3g@ is Megaa, <d0t> is a period or dot as in dot com, etc. -

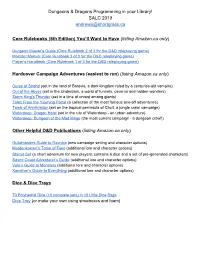

Dungeons & Dragons Programming in Your Library! SALC 2019 Andrewp

Dungeons & Dragons Programming in your Library! SALC 2019 [email protected] Core Rulebooks (5th Edition) You’ll Want to Have (listing Amazon.ca only) Dungeon Master’s Guide (Core Rulebook 2 of 3 for the D&D roleplaying game) Monster Manual (Core Rulebook 3 of 3 for the D&D roleplaying game) Player’s Handbook (Core Rulebook 1 of 3 for the D&D roleplaying game) Hardcover Campaign Adventures (easiest to run) (listing Amazon.ca only) Curse of Strahd (set in the land of Barovia, a dark kingdom ruled by a centuries-old vampire) Out of the Abyss (set in the Underdark, a world of tunnels, caverns and hidden wonders) Storm King’s Thunder (set in a time of unrest among giants) Tales From the Yawning Portal (a collection of the most famous one-off adventures) Tomb of Annihilation (set on the tropical peninsula of Chult, a jungle crawl campaign) Waterdeep: Dragon Heist (set in the city of Waterdeep - an urban adventure) Waterdeep: Dungeon of the Mad Mage (the most current campaign - a dungeon crawl!) Other Helpful D&D Publications (listing Amazon.ca only) Guildmasters Guide to Ravnica (new campaign setting and character options) Mordenkainen’s Tome of Foes (additional lore and character options) Starter Set (a short adventure for new players; contains 6 dice and a set of pre-generated characters) Sword Coast Adventurer’s Guide (additional lore and character options) Volo’s Guide to Monsters (additional lore and character options) Xanathar’s Guide to Everything (additional lore and character options) -

Dungeons & Dragons

“A Living and Breathing World…”: Examining Participatory Practices Within Dungeons & Dragons by Corey Ryan Walden A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Communication (MCS) July 18, 2015 School of Communication Studies ii Copyright © 2015 by Corey Ryan Walden iii ABSTRACT Permeated and referenced throughout popular culture, Dungeons & Dragons has become iconic as the cardinal and archetypal tabletop role-playing game. Participants have been drawn to D&D for over forty years, departing into imagined and collaborative fantasy worlds. This thesis is concerned with analysing current participatory practices in D&D, accounting for evolving styles of hybridised gaming and retentions of traditional tabletop play. It ventures beyond initial conceptual enquiries, developing tangible conclusions to the questions: “How important is the idea of community when playing Dungeons & Dragons?” and “What is appealing about constructing fictitious identities within the group, actualised through notions of play?” To assist in answering these questions an Internet survey was developed. Survey data is presented, analysed, and contrasted with existing role-playing game scholarship. Emergent findings discuss participant experiences of “entertainment” “fantasy”, “community”, and preferred “D&D editions”. It is strongly contended that D&D transcends the superficialities associated with a “game”. Participants powerfully engage — transmuting participatory experiences into broader realms of purpose and meaning. The game facilitates the continual formation and negotiation of community and identity, demonstrating its wider socio-cultural applicability. The ability and appeal to engage with substantial identity exploration is clearly observable within D&D practices. The game offers participants accessibility into divergent paradigms of reality.