Reliability and Generalization in Early Modern Anatomy 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF the Bursa of Hieronymus Fabricius Ab

Rom J Morphol Embryol 2020, 61(2):583–585 ISSN (print) 1220–0522, ISSN (online) 2066–8279 doi: 10.47162/RJME.61.2.31 R J M E HORT ISTORICAL EVIEW Romanian Journal of S H R Morphology & Embryology http://www.rjme.ro/ The bursa of Hieronymus Fabricius ab Aquapendente: from original iconography to most recent research DOMENICO RIBATTI1), ANDREA PORZIONATO2), ARON EMMI2), RAFFAELE DE CARO2) 1)Department of Basic Medical Sciences, Neurosciences and Sensory Organs, University of Bari Medical School, Bari, Italy 2)Department of Neuroscience, Section of Anatomy, University of Padova Medical School, Padova, Italy Abstract Hieronymus Fabricius ab Aquapendente (1533–1619) described the homonymous bursa in the “De Formatione Ovi et Pulli”, published posthumously in 1621. He also included a figure in which the bursa was depicted. We here present the figure of the bursa of Fabricius, along with corrections of some mislabeling still presents in some anastatic copies. The bursa of Fabricius is universally known as the origin of B-lymphocytes; morphogenetical and physiological issues are also considered. Keywords: anatomical iconography, bursa of Fabricius, Hieronymus Fabricius ab Aquapendente. Hieronymus Fabricius ab Aquapendente was born in manuscript, there is the notation “* 3. F.”, as reference 1533, he graduated in medicine at the University of for the asterisk in the text; in fact, in the figure III of the Padua, and he was a student of Gabriel Falloppius. In manuscript (Figure 1, B and C), with the letter “F” is 1565, he became a professor of anatomy and surgery represented the “vesicular in quam gallus emittis semen” in Padua. -

Antony Van Leeuwenhoek, the Father of Microscope

Turkish Journal of Biochemistry – Türk Biyokimya Dergisi 2016; 41(1): 58–62 Education Sector Letter to the Editor – 93585 Emine Elif Vatanoğlu-Lutz*, Ahmet Doğan Ataman Medicine in philately: Antony Van Leeuwenhoek, the father of microscope Pullardaki tıp: Antony Van Leeuwenhoek, mikroskobun kaşifi DOI 10.1515/tjb-2016-0010 only one lens to look at blood, insects and many other Received September 16, 2015; accepted December 1, 2015 objects. He was first to describe cells and bacteria, seen through his very small microscopes with, for his time, The origin of the word microscope comes from two Greek extremely good lenses (Figure 1) [3]. words, “uikpos,” small and “okottew,” view. It has been After van Leeuwenhoek’s contribution,there were big known for over 2000 years that glass bends light. In the steps in the world of microscopes. Several technical inno- 2nd century BC, Claudius Ptolemy described a stick appear- vations made microscopes better and easier to handle, ing to bend in a pool of water, and accurately recorded the which led to microscopy becoming more and more popular angles to within half a degree. He then very accurately among scientists. An important discovery was that lenses calculated the refraction constant of water. During the combining two types of glass could reduce the chromatic 1st century,around year 100, glass had been invented and effect, with its disturbing halos resulting from differences the Romans were looking through the glass and testing in refraction of light (Figure 2) [4]. it. They experimented with different shapes of clear glass In 1830, Joseph Jackson Lister reduced the problem and one of their samples was thick in the middle and thin with spherical aberration by showing that several weak on the edges [1]. -

STAGES in the DEVELOPMENT of TRACHEOTOMY ADEBOLA, S.O OMOKANYE, H.K, AREMU, S.K Dept

STAGES IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF TRACHEOTOMY ADEBOLA, S.O OMOKANYE, H.K, AREMU, S.K Dept. Of Otorhinolaryngology, UI,T.H, Ilorin, Kwara State. Correspondence: Dr Adebola, S.O, Dept of ORL, UITH,Ilorin, Kwara State, Nigeria. Email address: [email protected] ABSTRACT Tracheostomy refers to a surgical procedure of distinguished historical evolution. It spans various periods, each having specific contributions to what obtains presently. Every resident doctor is encouraged to acquire the skill required for this live-saving procedure. INTRODUCTION Tracheostomy is one of the oldest operations, whose indications and methods of the operative technique have been reported since ancient times. The word „tracheostomy‟ is derived from two Greek words, tracheo and oma meaning „I cut trachea‟. It refers to a surgical procedure which involves an opening between the trachea and the skin surface of the neck in the midline, with the creation of a stoma1. The word tracheostomy first appeared in print in 1649, but was not commonly used until a century later when it was introduced by the German surgeon Lorenz Heister in 1718 2. The procedure has been given several different names, including pharyngotomy, laryngotomy, bronchotomy and tracheotomy. In Greek and Roman medicine, the operation was initially called laryngotomy or bronchotomy. The evolution and adaptation of tracheostomy, can be divided into 5 periods, according to McCIelland3 .The period of the Legend (2000BC to AD 1546); the period of Fear (1546 to 1833) when the operation was performed only by a brave few, often at the risk of their reputation; the period of Drama (1833 to 1932) during which the procedure was generally performed only in emergency situations on acutely obstructed patients; the period of enthusiasm (1932 to 1965) when the dictum, „if you think tracheostomy, then do it,‟became popular; the period of rationalization, (1965 to the present) when the relative merits of intubation versus tracheostomy were debated. -

Table of Contents

Tables of contents 3 Table of contents Foreword 7 Jan Van den Tweel, Gabriella Nesi Introduction 9 Fabio Zampieri, Alberto Zanatta, Cristina Basso, Gaetano Thiene First Part | Andreas Vesalius, 500 years later Some notes on Vesalius and the sixteenth-century anatomy 13 Massimo Rinaldi Andries van Wesele (Andreas Vesalius). His ancestors, his youth and his studies in Louvain 31 Inge Fourneau The frontispiece of Vesalius’ Fabrica 45 Andrea Meneghini Anatomical cultures based on the act of seeing 61 Gianni Moriani Andreas Vesalius’ epistemological revolution 89 Fabio Zampieri The concept of cardiovascular system in the Vesalius’ mind 135 Gaetano Thiene, Cristina Basso, Alberto Zanatta, Fabio Zampieri 4 Tables of contents Second Part | International Meeting on the History of Medicine and Pathology Section One | HISTORY OF MEDICINE AND PATHOLOGY A short history of cardiac surgery 151 Ugo Filippo Tesler The human Thymus: from antiquity to 19th century. Myths, facts, malefactions 179 Maria Teresa Ranieri, Mirella Marino, Antiquarian medical books in the 1650s 191 Vittoria Feola Surveillance of mortality in the General Hospital in Vienna in the 19th Century 213 Doris Hoeflmayer Nineteenth century Western Europe: the backdrop to unravelling the mystery of leukaemia 221 Kirsten Morris History of modern medicine and pathology: “A curious inquest” 235 Pranay Tanwar, Ritesh Kumar The Hapsburg Lip: a dominant trait of a dominant family 243 Rafael Jimenez Pathologists and CHD. History of the seminal contributions of pathologists to the understanding -

Galileo in Early Modern Denmark, 1600-1650

1 Galileo in early modern Denmark, 1600-1650 Helge Kragh Abstract: The scientific revolution in the first half of the seventeenth century, pioneered by figures such as Harvey, Galileo, Gassendi, Kepler and Descartes, was disseminated to the northernmost countries in Europe with considerable delay. In this essay I examine how and when Galileo’s new ideas in physics and astronomy became known in Denmark, and I compare the reception with the one in Sweden. It turns out that Galileo was almost exclusively known for his sensational use of the telescope to unravel the secrets of the heavens, meaning that he was predominantly seen as an astronomical innovator and advocate of the Copernican world system. Danish astronomy at the time was however based on Tycho Brahe’s view of the universe and therefore hostile to Copernican and, by implication, Galilean cosmology. Although Galileo’s telescope attracted much attention, it took about thirty years until a Danish astronomer actually used the instrument for observations. By the 1640s Galileo was generally admired for his astronomical discoveries, but no one in Denmark drew the consequence that the dogma of the central Earth, a fundamental feature of the Tychonian world picture, was therefore incorrect. 1. Introduction In the early 1940s the Swedish scholar Henrik Sandblad (1912-1992), later a professor of history of science and ideas at the University of Gothenburg, published a series of works in which he examined in detail the reception of Copernicanism in Sweden [Sandblad 1943; Sandblad 1944-1945]. Apart from a later summary account [Sandblad 1972], this investigation was published in Swedish and hence not accessible to most readers outside Scandinavia. -

Conservation Update for Robert Hooke's Micrographia

Slide 1 Conservation Update Robert Hooke’s Micrographia London:1667 Eliza Gilligan, Conservator for UVa Library [[email protected]] Hello, my name is Eliza Gilligan and I am the Conservator for University Library Collections at the University of Virginia. This slide show is a “re-broadcast” of a presentation I made at a library staff “Town Meeting” on September 16, 2011. I hope my notes to the slides fill in the gaps left by the transition from live presentation to this show, but if you have a question, please feel free to email me <[email protected]>. I’d like to share a little bit of information about the process of conservation treatment and also a little bit of information about what a unique opportunity conservation treatment provides in terms of examining the components of a book, using my recent treatment of Robert Hooke’s Micrographia as an example. Conservation of this title and many volumes from our circulating collections were made possible by a generous gift from Kathy Duffy, friend of the University Library Slide 2 What is Micrographia? The landmark publication that initiated the field of microscopy. The first edition was published in London in 1665. Robert Hooke described his use of a microscope for direct observation, provided text of his findings but most importantly, large illustrations to demonstrate his findings. The UVa Library copy is from the second issue printed in 1667. Eliza Gilligan, Conservator for UVa Library [[email protected]] This book was brought to my attention by a faculty member of the Rare Book School who uses it every year in her History of Illustration class. -

Mayo Foundation House Window Illustrates the Eras of Medicine

FEATURE HISTORY IN STAINED GLASS Mayo Foundation House window illustrates the eras of medicine BY MICHAEL CAMILLERI, MD, AND CYNTHIA STANISLAV, BS 12 | MINNESOTA MEDICINE | MARCH/APRIL 2020 FEATURE Mayo Foundation House window illustrates the eras of medicine BY MICHAEL CAMILLERI, MD, AND CYNTHIA STANISLAV, BS Doctors and investigators at Mayo Clinic have traditionally embraced the study of the history of medicine, a history that is chronicled in the stained glass window at Mayo Foundation House. Soon after the donation of the Mayo family home in Rochester, Minnesota, to the Mayo Foundation in 1938, a committee that included Philip Showalter Hench, MD, (who became a Nobel Prize winner in 1950); C.F. Code, MD; and Henry Frederic Helmholz, Jr., MD, sub- mitted recommendations for a stained glass window dedicated to the history of medicine. The window, installed in 1943, is vertically organized to represent three “shields” from left to right—education, practice and research—over four epochs, starting from the bot- tom with the earliest (pre-1500) and ending with the most recent (post-1900) periods. These eras represent ancient and medieval medicine, the movement from theories to experimentation, organized advancement in science and, finally, the era of preventive medicine. The luminaries, their contributions to science and medicine and the famous quotes or aphorisms included in the panels of the stained glass window are summa- rized. Among the famous personalities shown are Hippocrates of Kos, Galen, Andreas Vesalius, Ambroise Paré, William Harvey, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, Giovanni Battista Morgagni, William Withering, Edward Jenner, René Laennec, Claude Bernard, Florence Nightingale, Louis Pasteur, Joseph Lister, Theodor Billroth, Robert Koch, William Osler, Willem Einthoven and Paul Ehrlich. -

Historical Review of Tracheostomy O Rajesh, R Meher

The Internet Journal of Otorhinolaryngology ISPUB.COM Volume 4 Number 2 Historical Review Of Tracheostomy O Rajesh, R Meher Citation O Rajesh, R Meher. Historical Review Of Tracheostomy. The Internet Journal of Otorhinolaryngology. 2005 Volume 4 Number 2. Abstract Tracheostomy is a life saving procedure done to establish airway in-patients with upper respiratory tract obstruction. It requires an opening to be made in anterior wall of trachea and a tube is inserted through the opening to allow passage of air and removal of secretions. Instead of breathing through the nose and mouth, the patient now breathes through the tracheostomy tube. If we look into history, the tracheotomy is one of the oldest surgical procedures, which was dreaded with complications until 19th century when procedure was understood clearly and indications properly defined. Authors review the history of tracheostomy from ancient period to the present era of surgical advancement. THE ORIGIN OF THE TERM TRACHEOSTOMY from 1500 BC to 1500 AD) begins with references to The word tracheostomy is derived from two words meaning incisions into the “wind pipe” in the Ebers Papyrus. The I cut trachea in Greek The procedure has been given several Rig-Veda a Hindu text circa 2000 BC describes spontaneous different names, including pharyngotomy, laryngotomy, healing of a tracheotomy incision. The first instance of bronchotomy, tracheostomy and tracheotomy. In Greek and tracheotomy was portrayed way back in 3600 BC on Roman medicine, the operation was initially called Egyptian artifacts by engravings in Abydos and Sakkara laryngotomy or bronchotomy. The word tracheotomy first regions of Egypt depicting tracheostomy. -

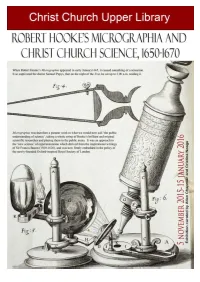

Robert Hooke's Micrographia

Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 is curated by Allan Chapman and Cristina Neagu, and will be open from 5 November 2015 to 15 January 2016. An exhibition to mark the 350th anniversary of the publication of Robert Hooke's Micrographia, the first book of microscopy. The event is organized at Christ Church, where Hooke was an undergraduate from 1653 to 1658, and includes a lecture (on Monday 30 November at 5:15 pm in the Upper Library) by the science historian Professor Allan Chapman. Visiting hours: Monday: 2.00 pm - 4.30 pm; Tuesday - Thursday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm; 2.00 pm - 4.00 pm; Friday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm Article on Robert Hooke and Early science at Christ Church by Allan Chapman Scientific equipment on loan from Allan Chapman Photography Alina Nachescu Exhibition catalogue and poster by Cristina Neagu Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Early Science at Christ Church, 1660-1670 Micrographia, Scheme 11, detail of cells in cork. Contents Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 Exhibition Catalogue Exhibits and Captions Title-page of the first edition of Micrographia, published in 1665. Robert Hooke’s Micrographia and Christ Church Science, 1650-1670 When Robert Hooke’s Micrographia: or Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses with Observations and Inquiries thereupon appeared in early January 1665, it caused something of a sensation. It so captivated the diarist Samuel Pepys, that on the night of the 21st, he sat up to 2.00 a.m. -

Milestones in Botany Botany Begins with Aristotle by Ruth A

Milestones in Botany Botany Begins with Aristotle By Ruth A. Sparrow Again this year Hobbies will give its readers glimpses of the rare first and early editions in the Milestones of Science Collection. Ruth A. Sparrow, Librarian, writes Milestones in Botany as the sixth in her series.—Editor's Note. • • • Living plants are found in all plants, many of them noted for their parts of the world in more or less pro- medicinal value. fusion. The mountain top and the Dioscorides (c. 50 A. D.), a con- desert each has its particular growth. temporary of Pliny, was a Greek bot- The science of this vegetation is bot- anist and physician in the Roman any. Plants from the smallest micro- army. He traveled extensively in this scopic plant to the largest tree have latter capacity and became intensely in- been of interest to man, for they pro- terested in botany. As a result of this vided him with food, shelter, medicine, combination of profession and hobby clothing, transportation, and other ne- he became the greatest of medical bot- cessities and comforts. All these were anists. He knew over six hundred material interests, and for centuries no plants which he has described in Ma- systematic study of plants was under- teria Medica (Venice, 1499). This taken. work holds an important place both in Aristotle (c. 350 B. C.) is credited the history of medicine and botany. as the first patron of botany and the As late as the seventeenth century no first so-called director of a botanic gar- drug was considered genuine that did den. -

Circulatory System 1 Circulatory System

Circulatory system 1 Circulatory system Circulatory system The human circulatory system. Red indicates oxygenated blood, blue indicates deoxygenated. Latin systema cardiovasculare The circulatory system is an organ system that passes nutrients (such as amino acids and electrolytes), gases, hormones, blood cells, etc. to and from cells in the body to help fight diseases and help stabilize body temperature and pH to maintain homeostasis. This system may be seen strictly as a blood distribution network, but some consider the circulatory system as composed of the cardiovascular system, which distributes blood,[1] and the lymphatic system,[2] which distributes lymph. While humans, as well as other vertebrates, have a closed cardiovascular system (meaning that the blood never leaves the network of arteries, veins and capillaries), some invertebrate groups have an open cardiovascular system. The most primitive animal phyla lack circulatory systems. The lymphatic system, on the other hand, is an open system. Two types of fluids move through the circulatory system: blood and lymph. The blood, heart, and blood vessels form the cardiovascular system. The lymph, lymph nodes, and lymph vessels form the lymphatic system. The cardiovascular system and the lymphatic system collectively make up the circulatory system. Human cardiovascular system The main components of the human cardiovascular system are the heart and the blood vessels.[3] It includes: the pulmonary circulation, a "loop" through the lungs where blood is oxygenated; and the systemic circulation, a "loop" through the rest of the body to provide oxygenated blood. An average adult contains five to six quarts (roughly 4.7 to 5.7 liters) of blood, which consists of plasma, red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets. -

Shakespeare's Medical Knowledge: How Did He Acquire

Shakespeare’s Medical Knowledge: How Did He Acquire It? Frank M. Davis, M.D. ❦ OLUMES have been written on the subject of Shakespeare’s knowledge of legal language and issues, most of it by lawyers, all but a handful arguing strenuously that he had, as Lord Penzance stated, “a knowledge [of the law] so perfect and intimate that he was never incorrect and never at fault.” (Greenwood 375). A number of scholars have felt the same way about his knowledge of medicine. As E.K. Chambers said, “on similar grounds [referring to the law] Shakespeare has been repre- sented as an apothecary and a student of medicine” (1.23). Yet there have been only three comprehensive books written on the subject of Shakespeare’s knowledge of medicine: J.C. Bucknill (1860); R.R. Simpson (1959); and Aubrey C. Kail (1986); along with a handful of less important works (see Selected Bibliography, page 58) . Let’s examine what Shakespeare might have known about medicine in his day. First, it is important to note that there would be no comprehensive books on the history of medicine of the period until 1699, when Drs. Baden and Drake translated into English the L’Histoire du Physique of Le Clerc, and even this dealt primarily with the medicine of the Greeks and Arabs (Bucknill 10). Although there were at the time a number of essays or short works on narrow medical issues, true medical literature, like medicine itself, was still in its infancy, so that it would not have been possible for Shakespeare to have absorbed much from reading what was available to him in English.