Ammannati at the Bargello

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discovering Florence in the Footsteps of Dante Alighieri: “Must-Sees”

1 JUNE 2021 MICHELLE 324 DISCOVERING FLORENCE IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF DANTE ALIGHIERI: “MUST-SEES” In 1265, one of the greatest poets of all time was born in Florence, Italy. Dante Alighieri has an incomparable legacy… After Dante, no other poet has ever reached the same level of respect, recognition, and fame. Not only did he transform the Italian language, but he also forever altered European literature. Among his works, “Divine Comedy,” is the most famous epic poem, continuing to inspire readers and writers to this day. So, how did Dante Alighieri become the father of the Italian language? Well, Dante’s writing was different from other prose at the time. Dante used “common” vernacular in his poetry, making it more simple for common people to understand. Moreover, Dante was deeply in love. When he was only nine years old, Dante experienced love at first sight, when he saw a young woman named “Beatrice.” His passion, devotion, and search for Beatrice formed a language understood by all - love. For centuries, Dante’s romanticism has not only lasted, but also grown. For those interested in discovering more about the mysteries of Dante Alighieri and his life in Florence , there are a handful of places you can visit. As you walk through the same streets Dante once walked, imagine the emotion he felt in his everlasting search of Beatrice. Put yourself in his shoes, as you explore the life of Dante in Florence, Italy. Consider visiting the following places: Casa di Dante Where it all began… Dante’s childhood home. Located right in the center of Florence, you can find the location of Dante’s birth and where he spent many years growing up. -

The Flowering of Florence: Botanical Art for the Medici" on View at the National Gallery of Art March 3 - May 27, 2002

Office of Press and Public Information Fourth Street and Constitution Av enue NW Washington, DC Phone: 202-842-6353 Fax: 202-789-3044 www.nga.gov/press Release Date: February 26, 2002 Passion for Art and Science Merge in "The Flowering of Florence: Botanical Art for the Medici" on View at the National Gallery of Art March 3 - May 27, 2002 Washington, DC -- The Medici family's passion for the arts and fascination with the natural sciences, from the 15th century to the end of the dynasty in the 18th century, is beautifully illustrated in The Flowering of Florence: Botanical Art for the Medici, at the National Gallery of Art's East Building, March 3 through May 27, 2002. Sixty-eight exquisite examples of botanical art, many never before shown in the United States, include paintings, works on vellum and paper, pietre dure (mosaics of semiprecious stones), manuscripts, printed books, and sumptuous textiles. The exhibition focuses on the work of three remarkable artists in Florence who dedicated themselves to depicting nature--Jacopo Ligozzi (1547-1626), Giovanna Garzoni (1600-1670), and Bartolomeo Bimbi (1648-1729). "The masterly technique of these remarkable artists, combined with freshness and originality of style, has had a lasting influence on the art of naturalistic painting," said Earl A. Powell III, director, National Gallery of Art. "We are indebted to the institutions and collectors, most based in Italy, who generously lent works of art to the exhibition." The Exhibition Early Nature Studies: The exhibition begins with an introductory section on nature studies from the late 1400s and early 1500s. -

A New Chronology of the Construction and Restoration of the Medici Guardaroba in the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence

A NEW CHRONOLOGY OF THE CONSTRUCTION AND RESTORATION OF THE MEDICI GUARDAROBA IN THE PALAZZO VECCHIO, FLORENCE by Mark Rosen One of the most unusual projects overseen by Giorgio Vasari in the Palazzo Vecchio in Flor- ence, the Guardaroba is a trapezoidal room containing a late-sixteenth-century cycle of fi fty-three geographical maps of the earth affi xed in two tiers to the front of a series of wooden cabinets (fi g. 1). Vasari published a detailed program for the Guardaroba project in the second edition of “Le vite de’ piu eccellenti pittori scultori e architettori” in 15681, at a moment when the project, begun in 1563, was still in development. The program defi nes it as a complete cosmography of the known universe, with maps, globes, painted constellations, illustrations of fl ora and fauna, and portraits of great historical leaders. Rarities and artworks placed inside the cabinets would act together with this custom-designed imagery to refl ect back on the name and charismatic persona of Vasari’s patron, Cosimo I de’ Medici (1519–1574). The idea and program behind the Medici Guardaroba had roots in late medieval studioli — small, womb-like study spaces that valorized private contemplation and collecting through complex humanistic decoration. Yet the goal of this new space was to be a public theater for the court’s cosmography and its power to collect and sort the duchy’s fi nest objects. The incomplete status of the room today — which includes only a series of empty cabinets, a terrestrial globe (1564–1568) by the Dominican scientist Egnazio Danti, and a cycle of maps painted by Danti (between 1563 and 1575) and Stefano Buonsignori (from 1576 through c. -

International Journal for Digital Art History, Issue #2

Artistic Data and Network Analysis Figure 1. Aby Warburg’s Panel 45 with the color version of the images mapped over the black-and-white photographic reproductions. Peer-Reviewed Images as Data: Cultural Analytics and Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Stefka Hristova Abstract: In this paper, by extending the methodology of media archaeology to the praxis of Cultural Analytics/Media Visualization I ask how have we compared multitude of diverse images and what can we learn about the narratives that these comparisons allow? I turn to the work of Aby Warburg who attempted to organize close to two thousand images in his Mnemosyne Atlas. In comparing contemporary methods of image data visualization through cultural analytics method of remapping and the turn of the century methodology developed by Warburg under the working title of the “iconology of intervals,” I examine the shifts and continuities that have shaped informational aesthetics as well as data-driven narratives. Furthermore, in drawing parallels between contemporary Cultural Analytics/Media Visualization techniques, and Aby Warburg’s Atlas, I argue that contextual and image color data knowledge should continue to be important for digital art history. More specifically, I take the case study of Warburg’s Panel 45 in order to explore what we can learn through different visualization techniques about the role of color in the representation of violence and the promise of prosperous civil society. Keywords: images as data, Aby Warburg, Cultural Analytics, color, visualization, violence, reconciliation In their current state, the methods information about the artifact. In this of Cultural Analytics and Digital project, I take on a hybrid Digital Art Humanities provide two radically Historical methodology that combines different ways of interpreting images. -

Sources of Donatello's Pulpits in San Lorenzo Revival and Freedom of Choice in the Early Renaissance*

! " #$ % ! &'()*+',)+"- )'+./.#')+.012 3 3 %! ! 34http://www.jstor.org/stable/3047811 ! +565.67552+*+5 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=caa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org THE SOURCES OF DONATELLO'S PULPITS IN SAN LORENZO REVIVAL AND FREEDOM OF CHOICE IN THE EARLY RENAISSANCE* IRVING LAVIN HE bronze pulpits executed by Donatello for the church of San Lorenzo in Florence T confront the investigator with something of a paradox.1 They stand today on either side of Brunelleschi's nave in the last bay toward the crossing.• The one on the left side (facing the altar, see text fig.) contains six scenes of Christ's earthly Passion, from the Agony in the Garden through the Entombment (Fig. -

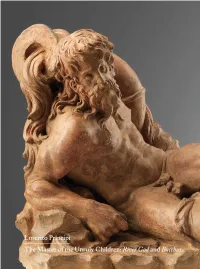

The Master of the Unruly Children: River God and Bacchus TRINITY

TRINITY FINE ART Lorenzo Principi The Master of the Unruly Children: River God and Bacchus London February 2020 Contents Acknowledgements: Giorgio Bacovich, Monica Bassanello, Jens Burk, Sara Cavatorti, Alessandro Cesati, Antonella Ciacci, 1. Florence 1523 Maichol Clemente, Francesco Colaucci, Lavinia Costanzo , p. 12 Claudia Cremonini, Alan Phipps Darr, Douglas DeFors , 2. Sandro di Lorenzo Luizetta Falyushina, Davide Gambino, Giancarlo Gentilini, and The Master of the Unruly Children Francesca Girelli, Cathryn Goodwin, Simone Guerriero, p. 20 Volker Krahn, Pavla Langer, Guido Linke, Stuart Lochhead, Mauro Magliani, Philippe Malgouyres, 3. Ligefiguren . From the Antique Judith Mann, Peta Motture, Stefano Musso, to the Master of the Unruly Children Omero Nardini, Maureen O’Brien, Chiara Padelletti, p. 41 Barbara Piovan, Cornelia Posch, Davide Ravaioli, 4. “ Bene formato et bene colorito ad imitatione di vero bronzo ”. Betsy J. Rosasco, Valentina Rossi, Oliva Rucellai, The function and the position of the statuettes of River God and Bacchus Katharina Siefert, Miriam Sz ó´cs, Ruth Taylor, Nicolas Tini Brunozzi, Alexandra Toscano, Riccardo Todesco, in the history of Italian Renaissance Kleinplastik Zsófia Vargyas, Laëtitia Villaume p. 48 5. The River God and the Bacchus in the history and criticism of 16 th century Italian Renaissance sculpture Catalogue edited by: p. 53 Dimitrios Zikos The Master of the Unruly Children: A list of the statuettes of River God and Bacchus Editorial coordination: p. 68 Ferdinando Corberi The Master of the Unruly Children: A Catalogue raisonné p. 76 Bibliography Carlo Orsi p. 84 THE MASTER OF THE UNRULY CHILDREN probably Sandro di Lorenzo di Smeraldo (Florence 1483 – c. 1554) River God terracotta, 26 x 33 x 21 cm PROVENANCE : heirs of the Zalum family, Florence (probably Villa Gamberaia) THE MASTER OF THE UNRULY CHILDREN probably Sandro di Lorenzo di Smeraldo (Florence 1483 – c. -

Leon Battista Alberti

THE HARVARD UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR ITALIAN RENAISSANCE STUDIES VILLA I TATTI Via di Vincigliata 26, 50135 Florence, Italy VOLUME 25 E-mail: [email protected] / Web: http://www.itatti.ita a a Tel: +39 055 603 251 / Fax: +39 055 603 383 AUTUMN 2005 From Joseph Connors: Letter from Florence From Katharine Park: he verve of every new Fellow who he last time I spent a full semester at walked into my office in September, I Tatti was in the spring of 2001. It T This year we have two T the abundant vendemmia, the large was as a Visiting Professor, and my Letters from Florence. number of families and children: all these husband Martin Brody and I spent a Director Joseph Connors was on were good omens. And indeed it has been splendid six months in the Villa Papiniana sabbatical for the second semester a year of extraordinary sparkle. The bonds composing a piano trio (in his case) and during which time Katharine Park, among Fellows were reinforced at the finishing up the research on a book on Zemurray Stone Radcliffe Professor outset by several trips, first to Orvieto, the medieval and Renaissance origins of of the History of Science and of the where we were guided by the great human dissection (in mine). Like so Studies of Women, Gender, and expert on the cathedral, Lucio Riccetti many who have worked at I Tatti, we Sexuality came to Florence from (VIT’91); and another to Milan, where were overwhelmed by the beauty of the Harvard as Acting Director. Matteo Ceriana guided us place, impressed by its through the exhibition on Fra scholarly resources, and Carnevale, which he had helped stimulated by the company to organize along with Keith and conversation. -

Musei Di Firenze ON-LINE POSSIBILITÀ DI ACQUISTARE BIGLIETTI CUMULATIVI CON SCONTI PER I DIVERSI MUSEI

PRENOTAZIONI ONLINE È POSSIBILE PRENOTARE I Musei di Firenze ON-LINE POSSIBILITÀ DI ACQUISTARE BIGLIETTI CUMULATIVI CON SCONTI PER I DIVERSI MUSEI. VISITA IL SITO FIRENZEMUSEI.IT I N G R E S S O L I B E R O Per i cittadini della Comunità europea Per i ragazzi sotto i 18 anni FIRENZE CARD Per gli adulti oltre i 65 DÀ ACCESSO AI PRINCIPALI MUSEI Per i cittadini non comunitari, ED E' VALIDA 72 ORE. l'ingresso è gratuito per i bambini NEL CASO IN CUI SI DECIDA DI sotto i 6 anni. VISITARE SOLO GLI UFFIZI E È necessario pagare solo la L'ACCADEMIA NON È CONVENIENTE. prenotazione di 4,00€ a persona. PREZZO DI OGNI MUSEO CON Per ulteriori informazioni visitare PRENOTAZIONE: CIRCA 15,00€ PER il sito sbas.firenze.it o PERSONA firenzemusei.it PRENOTAZIONI ONLINE VISITA IL SITO I Musei di Firenze FIRENZEMUSEI.IT L A G A L L E R I A D E L L ' A C C A D E M I A LA GALLERIA DELL'ACCADEMIA VIA RICASOLI, 60 - TEL. 0039 055 2388609 APERTO DAL MARTEDÌ ALLA DOMENICA 8:30-18:50 - CHIUSO IL LUNEDI CI SONO SETTE OPERE DI MARMO DI MICHELANGELO: IL DAVID, S. MATTEO, QUATTRO PRIGIONIERI INCOMPIUTI, LA PIETÀ DI PALESTRINA . NELLE SALE CIRCOSTANTI, VI È LA PIÙ IMPORTANTE PINACOTECA DELLA CITTÀ DOPO GLI UFFIZI E PITTI, CON OPERE DEI PRIMITIVI E ARTISTI FIORENTINI E TOSCANI DEI SECOLI XIV E XV. L A G A L L E R I A D E G L I U F F I Z I PIAZZALE DEGLI UFFIZI - TEL . -

Gender Dynamics in Renaissance Florence Mary D

Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal Vol. 11, No. 1 • Fall 2016 The Cloister and the Square: Gender Dynamics in Renaissance Florence Mary D. Garrard eminist scholars have effectively unmasked the misogynist messages of the Fstatues that occupy and patrol the main public square of Florence — most conspicuously, Benvenuto Cellini’s Perseus Slaying Medusa and Giovanni da Bologna’s Rape of a Sabine Woman (Figs. 1, 20). In groundbreaking essays on those statues, Yael Even and Margaret Carroll brought to light the absolutist patriarchal control that was expressed through images of sexual violence.1 The purpose of art, in this way of thinking, was to bolster power by demonstrating its effect. Discussing Cellini’s brutal representation of the decapitated Medusa, Even connected the artist’s gratuitous inclusion of the dismembered body with his psychosexual concerns, and the display of Medusa’s gory head with a terrifying female archetype that is now seen to be under masculine control. Indeed, Cellini’s need to restage the patriarchal execution might be said to express a subconscious response to threat from the female, which he met through psychological reversal, by converting the dangerous female chimera into a feminine victim.2 1 Yael Even, “The Loggia dei Lanzi: A Showcase of Female Subjugation,” and Margaret D. Carroll, “The Erotics of Absolutism: Rubens and the Mystification of Sexual Violence,” The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History, ed. Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), 127–37, 139–59; and Geraldine A. Johnson, “Idol or Ideal? The Power and Potency of Female Public Sculpture,” Picturing Women in Renaissance and Baroque Italy, ed. -

Florence Celebrates the Uffizi the Medici Were Acquisitive, but the Last of the Line Was Generous

ArtNews December 1982 Florence Celebrates The Uffizi The Medici were acquisitive, but the last of the line was generous. She left all the family’s treasures to the people of Florence. by Milton Gendel Whenever I vist The Uffizi Gallery, I start with Raphael’s classic portrait of Leo X and Two Cardinals, in which the artist shows his patron and friend as a princely pontiff at home in his study. The pope’s esthetic interests are indicated by the finely worked silver bell on the red-draped table and an illuminated Bible, which he has been studying with the aid of a gold-mounted lens. The brass ball finial on his chair alludes to the Medici armorial device, for Leo X was Giovanni de’ Medici, the second son of Lorenzo the Magnificent. Clutching the chair, as if affirming the reality of nepotism, is the pope’s cousin, Cardinal Luigi de’ Rossi. On the left is Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici, another cousin, whose look of reverie might be read, I imagine, as foreseeing his own disastrous reign as Pope Clement VII. That was five years in the future, of course, and could not have been anticipated by Raphael, but Leo had also made cardinals of his three nephews, so it wasn’t unlikely that another member of the family would be elected to the papacy. In fact, between 1513 and 1605, four Medici popes reigned in Rome. Leo X was a true Renaissance prince, whose civility and love of the arts impressed everyone - in the tradition of his father, Lorenzo the Magnificent. -

Celebrating the City: the Image of Florence As Shaped Through the Arts

“Nothing more beautiful or wonderful than Florence can be found anywhere in the world.” - Leonardo Bruni, “Panegyric to the City of Florence” (1403) “I was in a sort of ecstasy from the idea of being in Florence.” - Stendahl, Naples and Florence: A Journey from Milan to Reggio (1817) “Historic Florence is an incubus on its present population.” - Mary McCarthy, The Stones of Florence (1956) “It’s hard for other people to realize just how easily we Florentines live with the past in our hearts and minds because it surrounds us in a very real way. To most people, the Renaissance is a few paintings on a gallery wall; to us it is more than an environment - it’s an entire culture, a way of life.” - Franco Zeffirelli Celebrating the City: the image of Florence as shaped through the arts ACM Florence Fall, 2010 Celebrating the City, page 2 Celebrating the City: the image of Florence as shaped through the arts ACM Florence Fall, 2010 The citizens of renaissance Florence proclaimed the power, wealth and piety of their city through the arts, and left a rich cultural heritage that still surrounds Florence with a unique and compelling mystique. This course will examine the circumstances that fostered such a flowering of the arts, the works that were particularly created to promote the status and beauty of the city, and the reaction of past and present Florentines to their extraordinary home. In keeping with the ACM Florence program‟s goal of helping students to “read a city”, we will frequently use site visits as our classroom. -

THE FLORENTINE HOUSE of MEDICI (1389-1743): POLITICS, PATRONAGE, and the USE of CULTURAL HERITAGE in SHAPING the RENAISSANCE by NICHOLAS J

THE FLORENTINE HOUSE OF MEDICI (1389-1743): POLITICS, PATRONAGE, AND THE USE OF CULTURAL HERITAGE IN SHAPING THE RENAISSANCE By NICHOLAS J. CUOZZO, MPP A thesis submitted to the Graduate School—New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Art History written under the direction of Archer St. Clair Harvey, Ph.D. and approved by _________________________ _________________________ _________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May, 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS The Florentine House of Medici (1389-1743): Politics, Patronage, and the Use of Cultural Heritage in Shaping the Renaissance By NICHOLAS J. CUOZZO, MPP Thesis Director: Archer St. Clair Harvey, Ph.D. A great many individuals and families of historical prominence contributed to the development of the Italian and larger European Renaissance through acts of patronage. Among them was the Florentine House of Medici. The Medici were an Italian noble house that served first as the de facto rulers of Florence, and then as Grand Dukes of Tuscany, from the mid-15th century to the mid-18th century. This thesis evaluates the contributions of eight consequential members of the Florentine Medici family, Cosimo di Giovanni, Lorenzo di Giovanni, Giovanni di Lorenzo, Cosimo I, Cosimo II, Cosimo III, Gian Gastone, and Anna Maria Luisa, and their acts of artistic, literary, scientific, and architectural patronage that contributed to the cultural heritage of Florence, Italy. This thesis also explores relevant social, political, economic, and geopolitical conditions over the course of the Medici dynasty, and incorporates primary research derived from a conversation and an interview with specialists in Florence in order to present a more contextual analysis.