Heseltine Institute Working Paper Series Voices and Echoes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Riverside College C45 C46 C50

Valid from 7 September 2020 Bus timetable C39 C40 C42 C44 C44A Buses serving Riverside College C45 C46 C50 These services are provided by Warrington’s Own Buses www.merseytravel.gov.uk What’s changed? Route C50 is added to the timetable - operating between Huyton Bus Station and Riverside College. Route C44 and C44A morning journeys are retimed. Any comments about this service? If you’ve got any comments or suggestions about the services shown in this timetable, please contact the bus company who runs the service: Warrington’s Own Buses Wilderspool Causeway, Warrington, Cheshire, WA4 6PT. 0192 563 4296 If it’s a Merseytravel Bus Service we’d like to know what you think of the service, or if you have left something in a bus station, please contact us at Merseytravel: By e-mail [email protected] By phone 0151 330 1000 In writing PO Box 1976, Liverpool, L69 3HN Need some help or more information? For help planning your journey, call Traveline, open 0800 - 2000, 7 days a week on 0871 200 2233. You can visit one of our Travel Centres across the Merseytravel network to get information about all public transport services. To find out opening times, phone us on 0151 330 1000. Our website contains lots of information about public transport across Merseyside. You can visit our website at www.merseytravel.gov.uk Bus services may run to different timetables during bank and public holidays, so please check your travel plans in advance. Large print timetables We can supply this timetable in another format, such as large print. -

Registered Pharmacies 2021-02-04

The list of pharmacies registered to sell PPCs on our behalf is sorted alphabetically in postcode order. 0 NAME PREMISES ADDRESS 1 PREMISES ADDRESS 2 PREMISES ADDRESS 3 PREMISES ADDRESS 4 POSTCODE LLOYDS PHARMACY SAINSBURYS, EVERARD CLOSE ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 2QU BOOTS UK LIMITED 9 ST PETERS STREET ST.ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 3DH ST ALBANS PHARMACY 197 CELL BARNES LANE ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 5PX LLOYDS PHARMACY SAINSBURYS, BARNET ROAD LONDON COLNEY ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL2 1AB NORMANDY PHARMACY 52 WAVERLEY ROAD ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL3 5PE QUADRANT PHARMACY 17 THE QUADRANT MARSHALSWICK LANE ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL4 9RB BOOTS UK LIMITED 23-25 HIGH STREET HARPENDEN HERTFORDSHIRE AL5 2RU BOOTS UK LIMITED 65 MOORS WALK WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 2BQ PEARTREE PHARMACY 110 PEARTREE LANE WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 3UJ COHENS CHEMIST 1 ROBIN HOOD LANE HATFIELD HERTFORDSHIRE AL10 0LD BOOTS UK LIMITED 47 TOWN CENTRE HATFIELD HERTFORDSHIRE AL10 0LD BOOTS UK LIMITED 2A BRINDLEY PLACE BIRMINGHAM WEST MIDLANDS B1 2JB BOOTS UK LIMITED UNIT MSU 10A NEW BULL RING SHOP CTR BIRMINGHAM WEST MIDLANDS B2 4BE BOOTS UK LIMITED 102 NEW STREET BIRMINGHAM WEST MIDLANDS B2 4HQ BOOTS UK LIMITED 71 PERSHORE ROAD EDGBASTON BIRMINGHAM WEST MIDLANDS B5 7NX IPHARM UK LTD 4A, 11 JAMESON ROAD BIRMINGHAM WEST MIDLANDS B6 7SJ PHARMACO 2000 LTD UNIT 4 BOULTBEE BUSINESS UNITS NECHELLS PLACE BIRMINGHAM WEST MIDLANDS B7 5AR J DOCTER LTD BLOOMSBURY VILLAGE CENTRE 67 RUPERT STREET NECHELLS BIRMINGHAM B7 5DT MASTERS UK LTD 55 NECHELLS PARK -

Young People Adulthood

A guide to preparing young people age 14 to 25 with learning difficulties or disabilities for adulthood ...giving young people the best options in life Employment education | training | work | volunteering Health & Support sexual health | support | advice | mental health Independent Living & Housing groups | community | friends | respite Leisure groups | community | friends | activities This transition brochure is located on Wirral’s Local Offer: www.localofferwirral.org 2 This is... Your Future Your Choice This and more information can be found on Wirral’s Local Offer website. PLAN... PREPARE... JUST DO IT! or young people with a learning difficulty or Or maybe you need a bit of extra support to take part disability your transition years are crucial. in some activities. Whatever you choose to do with F Deciding what to do with your future can be a your future, you want to be sure that the help you difficult and worrying time. As you plan your career need can be provided. Finding out all of this path you may have concerns about what choices are information, making plans and decisions are key parts out there, what is the right thing to do and where you of your transition process. can get the best advice and guidance. Wirral’s Local Offer will help you to find out more Our hope is that this brochure will help you and your about the range of opportunities available to young family make the right choices. Wirral has a great people who have additional needs. You will be able choice of services covering: to learn more about the options and services that are available. -

NHS England Cheshire and Merseyside: Lots and Locations

NHS England Cheshire and Merseyside: Lots and locations Local Proposed Lot names Related wards Related post codes Authority / Location of (including but not provider exclusively) Cheshire Cheshire East (East) Alderley Edge, Bollington, Chelford, Congleton, CW4, CW12, SK9, SK10, East Disley, Handforth, Holmes Chapel, Knutsford, SK11, SK12, WA16 Macclesfield, Mobberley, Poynton, Prestbury, Wilmslow Cheshire East (South) Alsagar, Audlem, Crewe, Middlewich, Nantwich, CW1, CW2, CW5, CW10, Sandbach, Scholar Green, Wrenbury CW11, ST7 Cheshire Cheshire West & Barnton, Lostock Gralam, Northwich, Sandiway, CW7, CW8, CW9 West and Chester (East) Weaverham, Winsford Chester Cheshire West & Chester, Farndon, Malpas, Tarvin, Tattenhall, CH1, CH2, CH3, CH4, (includes Chester (West) Kelsall, Bunbury, Tarporley, Frodsham, Helsby, CW6, SY14, WA6 Vale Royal) Ellesmere Port, Neston, Great Sutton, Little Sutton, Neston, Elton, Willaston Halton Halton Hough Green, Runcorn, Widnes WA7,WA8 Knowsley - Halewood, Huyton, Kirkby, Stockbridge Village, L14, L25, L26, L28, L32, Whiston L33, L34, L35, L36 Liverpool Liverpool North Aintree, Warbreck, Fazakerley, Croxteth, L4, L5, L9, L10, L11, L13 Clubmoor, Norris Green, Kirkdale, Anfield, (Clubmoor) Everton, Walton Liverpool South Riverside, Toxteth, Prince’s Park, Greenbank, L1 (Riverside), L8,L12 Church, Woolton, St Michaels', Mossley Hill, (Greenbank),L17, L18, Aigburth, Cressington, Allerton, Hunts Cross, L19, L24, L25 Speke, Garston, Gatacre Liverpool East Central, Dovecot, Kensington, Fairfield, Tuebrook, L1 (Central), -

Property Name Tenure Type

Tenure Property Name Type GIA (m2) Region Local Area Team Dewey Road Leasehold 150 London North East London Maplestead Road Care Home Freehold 612 London North East London Abbey Medical Centre Leasehold 70 London North East London North East London NHS Treatment Centre Leasehold 2258 London North East London Edgware Community Hospital Freehold 0 London North East London Crowndale Centre Car Park Leasehold 0 London North East London Gospel Oak Health Centre Other 979 London North East London Clarence Road London Freehold 725 London North East London Barton House Health Centre Freehold 989 London North East London Barton House Health Centre Freehold 989 London North East London Ann Taylor Childrens Centre Licence 0 London North East London The Nightingales Health Centre (Land) Leasehold 0 London North East London Cranwich Surgery Licence 489 London North East London Daubeney Childrens Centre Licence 0 London North East London Homerton Hospital Licence 0 London North East London Homerton Row Licence 0 London North East London Somerford Grove - Land Freehold 0 London North East London Lawson Practice Licence 993 London North East London Hackney Learning Trust Licence 0 London North East London Lilliput Nursery Licence 0 London North East London Linden Childrens Centre Licence 0 London North East London Neaman Surgery Licence 824 London North East London Norwood Bearstead Licence 0 London North East London Seabright Childrens Centre Licence 0 London North East London Well Street Surgery Licence 0 London North East London Stamford Hill Community -

HGDD Invoice Template

Building on Community Strengths in Knowsley October 2012 A Joint Strategic Asset Assessment for Knowsley Conducted by Public Perspectives with Knowsley Public Health Team Building on Community Strengths in Knowsley Contents Introduction and background ........................................................................................... 1 Approach and methodology ............................................................................................. 1 Key findings ....................................................................................................................... 2 Making the most of Knowsley’s assets ........................................................................... 4 What next for Knowsley and asset based working?....................................................... 8 Appendix 1 - List of assets by area partnership ............................................................. 9 Appendix 2 - Area partnership asset maps ................................................................... 28 Appendix 3 - A view from outside Knowsley ................................................................. 32 For further information please contact: Ken Harrison Chris McBrien Area Relationship Director Public Health Programme Manager Directorate of Communities and Leisure Knowsley Public Health Team Knowsley Council NHS Knowsley / Knowsley Council Telephone: 0151 443 3033 Telephone: 0151 443 2641 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Building on Community Strengths in Knowsley -

Our-Times-Spring-2015-Low-Res.Pdf

Spring 2015 2 2 - 7 1 e g a p r l l o i f H s e n i r o t o t t i S F 6 1 - 1 1 e g a p e g a l l i V e g r d o i f r s b e k i c r o o t t In this issue… S S Community Clear Up’s Keep Our Estates Looking Great 3 2 How You Can Get Involved - 1 s r e o g f With Your Community a s p e i h r t o t o Garden Competition S B Entries Open Now www.villages.org.uk More than just a Landlord Welcome to the Spring Meet the Scheme Managers Edition of Villages have four Scheme Managers who manage the sheltered Our Times... accommodation schemes in both Fitton Hill and Stockbridge Village. The team includes Marie Morgan and Arthur Mason who are based in Stockbridge Spring is finally in the air, time to Village and Dana Murphy and Lesley Cutter who are based in Fitton Hill. dust off the cobwebs and venture outside again. The Scheme Managers are responsible for making residents are safe and will respond to any daily contact with sheltered accommodation safeguarding concerns. If the early Easter break has filled residents in order to establish their well-being whilst Dana Murphy said “We all really love our job, you with the joys of Spring we identifying and taking appropriate action in any have some great tips on page 7 mainly because we help our vulnerable tenants to areas of concern. -

Latest Investment Opportunities in Knowsley

OPPORTUNITIES Knowsley is one of only 14 areas of the UK to boast HALSNEAD a prestigious Garden Village development. GARDEN VILLAGE Halsnead Garden Village is Knowsley’s largest development site and one of the most prestigious Size opportunities within the Liverpool City Region. 430 acres The Garden Village will create a vibrant community 174 ha attracting new people and families into the area alongside new employment space, a country park, Knowsley Council / Private additional education provision and associated community facilities. Set across 430 acres, the development will bring the biggest change to Knowsley over the next 18 years. A masterplan for Halsnead Garden Village has now been agreed with a number of major housebuilders already engaged in pre-application enquires. Opportunities are still available to be involved in this major landmark development in the region. + 22.5 1 of only 14 1,600 33 hectacres of new homes hectacres Garden Villages employment of green in the UK land space 1 country park RESIDENTIAL Whitakers, Prescot Archway Road, Huyton Village Centre - 35.5 acres / 14.4 ha - 11 acres / 4.5 ha - Private - Knowsley Council Land available for approximately 240 A range of town centre sites are available quality executive homes, located just to support higher density residential off the primary route into Prescot development within a major mixed use Town Centre. development opportunity. North Huyton Phase 5, Huyton Land South of Cherryfield Drive, - 22 acres / 9 ha Kirkby Town Centre - Knowsley Council and Liverpool Archdiocese - 31 acres / 12.6 ha This site is a former school and playing - Knowsley Council field site with the potential to deliver Former school site located adjacent to Kirkby Town Centre, close to the regional around 350 aspirational new homes. -

Liverpool Area NE 241 .250.300 S L S T a M STRE

. T PAU 800 L STRE F D ET S O R 50 Kingsway (Wallasey) AL JUVEN X 838 L 892 .X2.X3 P C7 D L O AI 103 54 Tunnel services PLACE S A LE R V O Y GASCOY Liverpool City Centre Liverpool area NE 241 .250.300 S L S T A M STRE RE 831 ET 101 A 432.433.500 R ET C7 T 101 E . L R S T W U 122(some).210 T S L ROBERT 130 E O A A Includes Knowsley and South Sefton X A D LACE E P 52 .55.55 .56 SE P W H NAYLO RO T C7 H R STREET W PENCER STREE S T T . 20.47.52 RO D 101 E A D W S B T 101 A O N 101 E T. O G L T S R OND N R A RICHM O T R GREA T T L L D . R L E E S R T E D S T EV Public transport map and guide A C E S R A C7 . E S O S E T R T E E T O S 800 A T T W S C OW L R E R EL ’ R D S 103 N L L A T O S R M N 50 H I ST B R C 838 S H I S R A E R Y E EE 101 B Everton I A T G B G E I B A 103 T H V R U E G P N D F E Park T 21 A . -

STOCKBRIDGE WARD NOTICE of POLL Notice Is Hereby Given That

KNOWSLEY METROPOLITAN BOROUGH COUNCIL ELECTION OF A BOROUGH COUNCILLOR STOCKBRIDGE WARD NOTICE OF POLL Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of A BOROUGH COUNCILLOR for the STOCKBRIDGE Ward will be held on THURSDAY 3 MAY 2012, between the hours of 7am and 10pm. 2. The Number of BOROUGH COUNCILLORS to be elected is ONE 3. The names, addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated and the names of all the persons signing the Candidate’s nomination papers are as follows: Name of Candidate Address Description Names of Persons who have signed the Nomination Paper Andrew 13 Oakfield Grove National Front Margaret Welch Paul O'Brien BRENNUS Huyton Britain For the Michelle Dunn William Bryan Liverpool British Susan Lewis Collette Parkes L36 0SU Thomas J Gallagher Paul M Lawrenson Blood Maureen Neuling Lynette Tully Les 12 Elm House Liberal Democrats John A Ambrose David R Russell RIGBY Knowsley Park Millicent Ambrose Jennifer Russell Lane Elizabeth Higgs Sandra P Russell Prescot Richard Higgs Marie E Marner Merseyside David P Higgs Patricia Evans L34 3LY Bill 7 Rosewood Labour Party Dennis J Baum Amanda Westwell WEIGHTMAN Close Candidate Heather Weightman Laura A Missen Stockbridge Margaret M O'Sullivan Stephanie Tomlinson Village Maureen Clunan Helena Johnson Knowsley Alison Lewis Maria Brassel Merseyside L28 5RU 4. The situation of the Polling Stations for the above election and the Local Government electors entitled to vote are as follows: Description of Persons entitled to Vote Situation of Polling Stations Polling Station No Local Government Electors whose names appear on the Register of Electors for the said Electoral Area for the current year. -

LOW CARBON a Skills for Growth Agreement Contents

Liverpool City Region Skills for Growth LOW CARBON A Skills for Growth Agreement Contents Skills for Growth Agreement 3 Headline Actions 5 Sector Briefing - Low Carbon 7 Low Carbon Sector Composition 8 Low Carbon Sector Performance 10 Locating Sector Skills 10 Low Carbon Skills Profile 12 Low Carbon Job Types 12 Workforce Composition - Age Structure 13 Workforce Composition - Occupational Profile 15 Key Qualification Levels 16 Supply of Skills 18 STEM Skills 19 Training Provision - Low Carbon 24 Vocational Training - Apprenticeships 29 Vocational Training - Further Education 30 Low Carbon Careers Education and Recruitment Support 33 LIVERPOOL CITY REGION SKILLS FOR GROWTH: LOW CARBON 1 Current and Future Opportunities 36 Managing Demand 36 Anticipated Demand 39 Conclusions 58 Glossary 59 References 60 Skills for Growth Agreement 63 Appendices 65 Appendix 1 - List of level 2-4 Low Carbon provision 65 Appendix 2 - Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) Training voucher 77 scheme Appendix 3 - Sector Skills Councils and National Skills Academies 78 Relevant to Low Carbon Appendix 4 - Summary of LCEGS Sector, Liverpool City Region - 79 Key Data Appendix 5 - PAS 2030 Qualifications, competence and green 80 deal work Skills for Growth Appendix 6 - Institute of Environmental Management and 82 Assessment (IEMA) EIA Quality Mark Register Agreement Appendix 7 - Higher Education Provision relating to low carbon 84 This agreement, produced by the Liverpool City Region Labour Market in the Liverpool City Region Information Service, is one of a suite of agreements that will be produced for Appendix 8 - Specialist Skills requested within Green jobs 87 key sectors and employment locations within the City Region. -

Liverpool Route

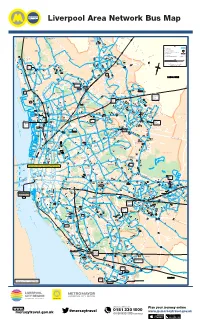

Liverpool Area Network Bus Map 300 to Halsall 310 to Ormskirk and Hightown S 206 to Hightown 47 to Southport and Crossens and Southport Skelmersdale A 31 31A N X2 to Southport and Preston Y DY A E L W A NE Weld S N P A A A MOSS H L N R A L T K Blundell D A L Lydiate NE R 310 T Y M W S O 47 C Arms D L O A A O N M L E S X2 L I L R U M A S F I 300 C N T K O R 31 K E O O O H (eve) E L O L A A R R A 31 P LA D R A M I N B 31 N O B N S B E H G E 300 E A U R A 31 206 R 31(some) turns:31(some) T T L C A L H L A E N A D E R N AS BE E N T LLS AD S E A E O O Key L LANE R A 31 R R L N RPOO Moss Wood E O LIVE 310 L Bus served roads D A D A A A N RO D O E L R L K T B WA E Bus route number 79 RK N O O PA N West Lancashire Y C W Little O O I N S K Golf Course C T S ER Bus route start/finish point 174 I GREEN O A E S Crosby N R N 47 O Y L R C L ANE A A A P G H 310 31 N R E Route operates in direction of arrow only X2 W E B E T E N 133 H E A A L C L U R T N K R L N G T O O Merseyrail stations A N 31 L 133 N LO N B A N G A U N L E R R 31 .310 T E E O E 32.33 C Croxteth A N A .