Knowsley Historic Settlement Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OCS0013 KMBC Draft 3 (Original):Layout 1 17/8/10 10:18 Page 1

OCS0013 KMBC draft 3 (original):Layout 1 17/8/10 10:18 Page 1 Wild Days Out in Knowsley is Major Events Calendar home to award winning, spectacular The North West's Green Borough attractions and offers visitors everything from May ELIZABETHAN FAYRE wildflowers to wildebeests. Prescot Town Centre Saturday 29th May, 11.30am – 4.30pm For more information 0151 430 7787 It is perfect for a day out - just eight miles from June KNOWSLEY GREEN FAYRE Liverpool City Centre and easily reached by train from National Wildflower Centre, Court Hey Park Liverpool Lime Street or Liverpool Central and by car Sunday 6th June 11am – 5pm from the M57 or M62. For more information 0151 443 3682 or 0151 443 5619 For more information about what Knowsley offers, July LIVERPOOL-KNOWSLEY INTERNATIONAL YOUTH SOCCER TOURNAMENT places to stay or public transport visit: Liverpool University Geoffrey Hughes Sports Complex Allerton Tuesday 27th July – Sunday 1st August www.visitknowsley.com For more information 0151 443 3627 or www.visitliverpool.com www.lksoccertournament.com www.knowsley.gov.uk August KNOWSLEY FLOWER SHOW National Wildflower Centre, Court Hey Park For travel info: Sunday 8th August 11am – 5pm www.letstravelwise.org For more information 0151 443 5619 or www.knowsleyflowershow.com www.merseytravel.gov.uk September AUTUMN HERITAGE FAYRE Bowring Park Community and Visitor Centre Sunday 12th September 11am – 4pm For more information 0151 482 1116 October BENGALI FESTIVAL Kirkby Suite - Wednesday 13th – Sunday 17th October 4pm – midnight For more information 0151 443 4063 November CHRISTMAS FAYRE AND MAGICAL GROTTO Bowring Park Community and Visitor Centre Sunday 28th November – Saturday 4th December 12 – 4pm For more information 0151 482 1116 sponsor logos here December WINTER CELEBRATION National Wildflower Centre Sunday 5th December 12 – 4pm For further information 0151 738 1913 www.visitknowsley.com Designed and produced by O’Connell & Squelch Ltd - www.ocands.co.uk Printed on recycled paper. -

SCRATCH COMPETITION Saturday 15 May 2021 the FORMBY HARE

SCRATCH COMPETITION Saturday 15 May 2021 FOR THE THE FORMBY HARE Holder: Greg Holmes Royal Birkdale Golf Club 36 HOLES STROKEPLAY The winner will receive a replica Formby Hare and a voucher. Other winners will be awarded vouchers as set out in the Conditions of Entry. The Lancashire Links Trophy For competitors entering both the Formby Hare and the Southport and Ainsdale Bowl, this will now be recognised as the ‘The Lancashire Links Trophy’ a World Amateur Golf Ranking Event. There will be prizes for the best three aggregate scores over the two competitions. Entrance Fee - £60.00 Cheques payable to Formby Golf Club ENTRIES CLOSE 4.30 pm THURSDAY 15 April 2021 FORMBY HARE CONDITIONS OF ENTRY, REGULATIONS AND PRIZES 1 Entries are invited from male Amateur members of recognised Golf Clubs with a handicap index of 3 or less. 2 Entries on the completed entry form together with the appropriate entrance fee must reach Elaine Black, Formby Golf Club, Golf Road, Formby, Merseyside L37 1LQ by 4.30pm, Thursday 15 April 2021. Enquiries: Monday to Friday 8.30am – 3.30pm, Telephone: 01704 872164 E-mail: [email protected] 3 The Organising Committee will make the draw and the order and times of starting will be posted / emailed to each competitor. All unsuccessful entrants will be advised. The draw will also be available on our website from Wednesday 21st April 2021. In the event of a competitor having to scratch, no entry fee will be returned. 4 The organising committee of the Formby Hare wish to ensure that slow play is avoided wherever possible. -

Riverside College C45 C46 C50

Valid from 7 September 2020 Bus timetable C39 C40 C42 C44 C44A Buses serving Riverside College C45 C46 C50 These services are provided by Warrington’s Own Buses www.merseytravel.gov.uk What’s changed? Route C50 is added to the timetable - operating between Huyton Bus Station and Riverside College. Route C44 and C44A morning journeys are retimed. Any comments about this service? If you’ve got any comments or suggestions about the services shown in this timetable, please contact the bus company who runs the service: Warrington’s Own Buses Wilderspool Causeway, Warrington, Cheshire, WA4 6PT. 0192 563 4296 If it’s a Merseytravel Bus Service we’d like to know what you think of the service, or if you have left something in a bus station, please contact us at Merseytravel: By e-mail [email protected] By phone 0151 330 1000 In writing PO Box 1976, Liverpool, L69 3HN Need some help or more information? For help planning your journey, call Traveline, open 0800 - 2000, 7 days a week on 0871 200 2233. You can visit one of our Travel Centres across the Merseytravel network to get information about all public transport services. To find out opening times, phone us on 0151 330 1000. Our website contains lots of information about public transport across Merseyside. You can visit our website at www.merseytravel.gov.uk Bus services may run to different timetables during bank and public holidays, so please check your travel plans in advance. Large print timetables We can supply this timetable in another format, such as large print. -

8–10 East Prescot Road, Liverpool L14 1Pw 7 Queens Road, Birkenhead

LOT 7 Queens road, birkenhead, merseyside cH42 1Qy 16 RESIDENTIAL INVESTMENT Guide price £125,000+ Ordnance Survey © Crown Copyright 2011. All rights reserved. Licence number 100020449 Licence reserved. rights 2011. All Copyright SurveyOrdnance © Crown Not to scale. For identification purposes only a residential investment currently let producing £19,440 Ground Floor Garden Flat second Floor per annum. the property comprises four self-contained flats Lounge, kitchen, bathroom, two Second Floor Flat Hall, lounge, (two two-bedroom, one one-bedroom, one three-bedroom) bedrooms, access to rear garden. kitchen, bathroom, two bedrooms. arranged over ground, first and second floors together with Let by way of Assured Shorthold Let by way of Assured Shorthold a self contained garden flat. the property benefits from Tenancy producing £395pcm. Tenancy producing £450pcm. double glazing and central heating. First Floor outside situated ground Floor First Floor Flat Hall, lounge, Front drive and rear garden. Queens Road runs directly off Kings Main entrance to communal hall kitchen, bathroom, three bedrooms, Road close to New Chester Road, Ground Floor Flat Hall, lounge, access to rear garden. Let by way Rock Ferry approximately 2 miles kitchen, bathroom, bedroom. Let by of Assured Shorthold Tenancy away from Birkenhead town centre. way of Assured Shorthold Tenancy procuding £450pcm. producing £325pcm. LOT 8–10 east prescot road, liverpool l14 1pW 17 VACANT COMMERCIAL Guide price £85,000+ Ordnance Survey © Crown Copyright 2011. All rights reserved. Licence number 100020449 Licence reserved. rights 2011. All Copyright SurveyOrdnance © Crown Not to scale. For identification purposes only a two storey mixed use mid terraced property comprising ground Floor a ground floor retail unit together with a three bedroomed Shop Main sales area, rear room, flat above which is accessed via a separate entrance. -

Tackling Crime and Disorder in St.Helens – Ward Update Rainford

TACKLING CRIME AND DISORDER IN ST.HELENS – WARD UPDATE RAINFORD The table below shows crime figures for a selection of crime and anti-social behaviour types for the period April to November 2008 and 2009. The overall reduction in crime and anti-social behaviour has been maintained and significant reductions are being experienced across the borough. One area of concern is the theft from motor vehicles where most Wards are showing increases compared to 2008. This may be a reflection of the current economic situation although other significant acquisitive crimes continue to show reductions. April to Nov April to Nov +/- % 2008/09 2009/10 Borough Wide Profile British Crime Survey Comparator Crimes 5134 4237 - 17.5% Total Recorded Crime 9239 8052 - 12.8% Ward Profile British Crime Survey Comparator Crimes 100 106 6.0% Total Recorded Crime 180 210 16.7% Theft of a Vehicle 15 5 - 66.7% Theft from a Vehicle 19 32 68.4% Domestic Burglary 13 24 84.6% Theft from a Person 0 0 Criminal Damage and Arson 34 21 -38.2% Drug Offences 28 37 32.1% Anti -Social Behaviour calls to the Police • Rowdy Behaviour 83 69 -16.9% • Nuisance Vehicles 4 11 175.0% • Street Drinking 3 0 - 100.0% Merseyside Police - Your Neighbourhood Inspector is Ian Cooper and your Neighbourhood Sergeant is Bob Clewes. Crime and Disorder Reduction Partnership Annual Report and Survey The CDRP annual report and survey was sent out to St. Helens residents in December 2009. The annual report reviews what St. Helens Council and Crime Reduction Partners have done and what we are going to do towards tackling anti- social behaviour, crime and disorder in St. -

Northern Line Train Times 18 May to 4 October 2014

Northern Line May 2014 Cover.qxp 14/03/2014 11:17 Page 1 Northern Line Train Times 18 May to 4 October 2014 Hunts Cross or Liverpool - Southport, Kirkby or Ormskirk Ormskirk - Preston Kirkby or Southport - Wigan - Manchester This timetable has been produced by Merseytravel on behalf of the featured Train Operating Companies Why not hire a bike? A brilliant bike hire scheme for train passengers is now available at a selection of Merseyrail stations. Bike & Go means you can quickly and easily continue your journey under your own steam, allowing you to hire a bike for only £3.80 a day. No more worrying about getting your own bike on the train, simply get off the train hire your bike and go. Visit www.bikeandgo.co.uk to find out more and to register for annual subscription. Go Cycle storage facilities allow you to store your own bike safely and securely at a number of stations across the Merseyrail network FREE of charge. Register for a FREE Go Cycle storage fob at www.merseyrail.org/gocycle northern line page 1 may 2014.qxp 26/03/2014 16:02 Page 1 Network news ... May 2014... May 2014... May 2014... May 2014... May 2014... May 2014... May... M A new look for Timetable index Route Page your trains Southport to Hunts Cross 2-5 Trains on the Merseyrail network are getting a brand Hunts Cross to Southport 6-10 new look. A new train livery is now being applied to Ormskirk and Kirkby to Liverpool 11-13 the whole fleet that gives your trains a brand new, fresh and exciting look and feel. -

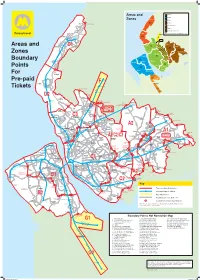

Zones-Map-June-18.Pdf

Areas and Zones SOUTHPORT 187 D1 CROSSENS Crossens/Plough Hotel Fylde Rd. Rd. New Preston La. Rd. idge Bankfield Cambr FORMBY CHURCHTOWN ORMSKIRK Rd. La. Roe SOUTHPORT Queens Park D2 MEOLS Lane St. SOUTHPORT COP Old F Sussex Lord Rd. F/C3 Duke St. BLOWICK Rd. MAGHULL Westbourne RAINFORD BIRKDALE La. CROSBY Areas and D1Town BILLINGE BIRKDALE C3 KEW KIRKBY A2 A3/C2/C3 HILLSIDE A1 Road BOOTLE Zones A1/A2 NEWTON-LE-WILLOWS WEST DERBY ST HELENS Liverpool PRESCOT WALLASEY C1 RAINHILL Shore HUYTON Boundary Rd. B1 LIVERPOOL AINSDALE BIRKENHEAD WEST KIRBY C2 GARSTON Points Pinfold HALEWOOD Lane B2 183 SPEKE HESWALL Liverpool Rd./ BROMBOROUGH Woodvale For Camp Gate WOODVALE HOOTON G1 ELLESMERE FRESHFIELD PORT ORMSKIRK Pre-paid Church Rd. Rd. gton F FORMBY CAPENHURST FORMBY Harin Duke St. AUGHTON PARK Tickets Rd. Alt Lydiate/Mairscough Brook G2 177 (RAILPASS ONLY) CHESTER Southport TOWN GREEN Rd. Lydiate/ D2 Robbins Island LYDIATE INCE 178 BLUNDELL Prescot Rd./ HIGHTOWN Park Cunscough La. Wall Rd. Northway Cunscough Lane East Park 170 171 Rainford, RAINFORD Long La./ Wheatsheaf Inn or RAINFORD Broad La. Lane 43 Ince MAGHULL CunscoughLane Ormskirk Road Terminus JUNCTION News La. 173 Lunt . Rd. Rd Ormskirk MAGHULL La. KINGS LUNT NORTH Live MOSS Rd. Poverty Rd Sth. Moss Vale/ LITTLE 176 rpool La. Bridges Prescot . Lane F/C3 La. Stork Inn CROSBY Long La./ Old THORNTON MAGHULL 10 Ince La. Lydiate Rd. Moor Bank RAINFORD La. Lane Cat North Ashton, Edge Hey Rock MELLING La. Newton HALL RD. Lane St. 11 Brocstedes Rd. Lane Red Rd. Moor La. La. 169 Shevingtons Higher C3 Main Garswoo TOWER HILL Church La. -

Building Canadian National Identity Within the State and Through Ice Hockey: a Political Analysis of the Donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 12-9-2015 12:00 AM Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893 Jordan Goldstein The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Robert K. Barney The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Kinesiology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Jordan Goldstein 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Intellectual History Commons, Political History Commons, Political Theory Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Goldstein, Jordan, "Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3416. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3416 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Stanley’s Political Scaffold Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893 By Jordan Goldstein Graduate Program in Kinesiology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Jordan Goldstein 2015 ii Abstract The Stanley Cup elicits strong emotions related to Canadian national identity despite its association as a professional ice hockey trophy. -

Sefton, West Lancashire, St Helens

LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND REVIEW OF MERSEYSIDE THE METROPOLITAN BOROUGH OF KNOWSLEY Boundaries with: SEFTON WEST LANCASHIRE ST HELENS HALTON (CHESHIRE) LIVERPOOL WEST LANCASHIRE SEFTON ST HELENS .IVERPOOL HALTON REPORT NO. 668 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND REPORT NO 668 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CHAIRMAN Mr K F J Ennals CB MEMBERS Mr G R Prentice Mrs H R V Sarkany Mr C W Smith Professor K Young THE RT HON MICHAEL HOWARD QC MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE ENVIRONMENT REVIEW OF MERSEYSIDE THE METROPOLITAN BOROUGH OF KNOWSLEY AND ITS BOUNDARIES WITH WEST LANCASHIRE, ST HELENS, HALTON (CHESHIRE), LIVERPOOL AND SEFTON COMMISSION'S FINAL REPORT INTRODUCTION 1 . This report contains our final proposals for the Metropolitan Borough of Knowsley's boundaries with the City of Liverpool, the Metropolitan Borough of St Helens, the District of West Lancashire in Lancashire, the Borough of Halton in Cheshire and part of its boundary with the Metropolitan Borough of Sefton. Our recommendations in respect of the review of the Borough of Sefton are contained in Report No. 664. We shall be reporting on the City of Liverpool's boundary with Sefton and Wirral separately. 2. Although during the course of the review we considered the possibility of radical changes to Knowsley, including its abolition, our final proposals involve major change only in relation to the Parish of Simonswood which we are proposing should be transferred to Lancashire. The remainder of our final proposals involve minor changes to Knowsley's boundaries to remove anomalies and defacements. 3. As required by Section 60(2) of the Local Government Act 1972, we have carefully considered all the representations made to us at each stage of the review. -

217, 217A (Bootle) Kirkby Bus Station - 227 Huyton Or Halewood These Services Are Provided by Stagecoach and Merseytravel

Valid from 30 August 2020 Bus timetable 217, 217A (Bootle) Kirkby Bus Station - 227 Huyton or Halewood These services are provided by Stagecoach and Merseytravel KIRKBY Bus Station KIRKBY ADMIN Bus Facility KNOWSLEY VILLAGE PAGE MOSS (daytime journeys) LONGVIEW Longview Drive (Eve/Sunday journeys) HUYTON Bus Station NAYLORSFIELD (Eve/Sunday journeys) BELLE VALE Shopping Centre (Eve/Sunday journeys) HUNTS CROSS Macketts Lane (Eve/Sunday journeys) HALEWOOD Shopping Centre (Eve/Sunday journeys) www.merseytravel.gov.uk 217 info page_info test 24/08/2020 14:52 Page 1 What’s changed? Service now runs as normal (as 19 January 2020 timetable). Any comments about this service? If you’ve got any comments or suggestions about the services shown in this timetable, please contact the bus company who runs the service: Stagecoach Merseyside East Lancashire Road, Gillmoss, Liverpool, L11 0BB 0151 330 6200 If it’s a Merseytravel Bus Service we’d like to know what you think of the service, or if you have left something in a bus station, please contact us at Merseytravel: By e-mail [email protected] By phone 0151 330 1000 In writing PO Box 1976, Liverpool, L69 3HN Need some help or more information? For help planning your journey, call 0151 330 1000, open 0800 - 2000, 7 days a week. You can visit one of our Travel Centres across the Merseytravel network to get information about all public transport services. To find out opening times, phone us on 0151 330 1000. Our website contains lots of information about public transport across Merseyside. You can visit our website at www.merseytravel.gov.uk Bus services may run to different timetables during bank and public holidays, so please check your travel plans in advance. -

Post 16 Provision Update for Local Offer

Preparing for Adulthood – Post 16 update for Local Offer The information below has been taken from the websites listed, which was written by the individual providers. This list does not reflect any endorsement by Halton Borough Council. It is merely a list of known providers to provide basic information about Post 16 Provision. Provision Contact Details Ashley School - Halton Mike Jones Head of 6th Form Maintained Special School Ashley High School Ashley High School 6th Form provides specialist Cawfield Avenue education for boys and girls, aged 16 to 19, with Widnes Asperger's Syndrome, higher-functioning autism and Cheshire social communication difficulties. The 6th form focus is WA8 7HG on continued core academic qualifications, a range of 0151 424 4892 vocational qualifications, preparation for adulthood and [email protected] career planning, whilst recognising the individual abilities and strengths of each student and enabling www.ashleyhighschool.co.uk them to reach their full potential. Bolton College – Greater Manchester Janet Bishop College of Further Education Head of Learner Support Bolton college provides high quality learning Bolton College opportunities and support throughout the curriculum, to Deane Road Bolton BL3 5BG learners with a wide range of disabilities and learning 01204 482654 difficulties including visual and hearing impairments, [email protected] mental health and emotional difficulties and autism. Learners can access a variety of vocational and www.boltoncollege.ac.uk/ prevocational courses -

The Story of a Man Called Daltone

- The Story of a Man called Daltone - “A semi-fictional tale about my Dalton family, with history and some true facts told; or what may have been” This story starts out as a fictional piece that tries to tell about the beginnings of my Dalton family. We can never know how far back in time this Dalton line started, but I have started this when the Celtic tribes inhabited Britain many yeas ago. Later on in the narrative, you will read factual information I and other Dalton researchers have found and published with much embellishment. There also is a lot of old English history that I have copied that are in the public domain. From this fictional tale we continue down to a man by the name of le Sieur de Dalton, who is my first documented ancestor, then there is a short history about each successive descendant of my Dalton direct line, with others, down to myself, Garth Rodney Dalton; (my birth name) Most of this later material was copied from my research of my Dalton roots. If you like to read about early British history; Celtic, Romans, Anglo-Saxons, Normans, Knight's, Kings, English, American and family history, then this is the book for you! Some of you will say i am full of it but remember this, “What may have been!” Give it up you knaves! Researched, complied, formated, indexed, wrote, edited, copied, copy-written, misspelled and filed by Rodney G. Dalton in the comfort of his easy chair at 1111 N – 2000 W Farr West, Utah in the United States of America in the Twenty First-Century A.D.