10 Image and Communication in the Seleucid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Heritage of India Series

THE HERITAGE OF INDIA SERIES T The Right Reverend V. S. AZARIAH, t [ of Dornakal. E-J-J j Bishop I J. N. FARQUHAR, M.A., D.Litt. (Oxon.). Already published. The Heart of Buddhism. K. J. SAUNDERS, M.A. Asoka. J. M. MACPHAIL, M.A., M.D. Indian Painting. PRINCIPAL PERCY BROWN, Calcutta. Kanarese Literature, 2nd ed. E. P. RICE, B.A. The Samkhya System. A. BERRIEDALE KEITH, D.C.L., D.Litt. Psalms of Maratha Saints. NICOL MACNICOL, M.A., D.Litt. A History of Hindi Literature. F. E. KEAY, M.A., D.Litt. The Karma-MImamsa. A. BERRIEDALE KEITH, D.C.L., D.Litt. Hymns of the Tamil Saivite Saints. F. KINGSBURY, B.A., and G. E. PHILLIPS, M.A. Rabindranath Tagore. E. J. THOMPSON, B.A., M.C. Hymns from the Rigveda. A. A. MACDONELL, M.A., Ph.D., Hon. LL.D. Gotama Buddha. K. J. SAUNDERS, M.A. Subjects proposed and volumes under Preparation. SANSKRIT AND PALI LITERATURE. Anthology of Mahayana Literature. Selections from the Upanishads. Scenes from the Ramayana. Selections from the Mahabharata. THE PHILOSOPHIES. An Introduction to Hindu Philosophy. J. N FARQUHAR and PRINCIPAL JOHN MCKENZIE, Bombay. The Philosophy of the Upanishads. Sankara's Vedanta. A. K. SHARMA, M.A., Patiala. Ramanuja's Vedanta. The Buddhist System. FINE ART AND MUSIC. Indian Architecture. R. L. EWING, B.A., Madras. Indian Sculpture. Insein, Burma. BIOGRAPHIES OF EMINENT INDIANS. Calcutta. V. SLACK, M.A., Tulsi Das. VERNACULAR LITERATURE. and K. T. PAUL, The Kurral. H. A. POPLBY, B.A., Madras, T> A Calcutta M. of the Alvars. -

Greek Past”: Religion, Tradition, Self

Acts of Identification and the Politics of the “Greek Past”: Religion, Tradition, Self by Vaia Touna A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Religious Studies University of Alberta © Vaia Touna, 2015 ABSTRACT This study is about a series of operational acts of identification, such as interpretations, categorizations, representations, classifications, through which past materials have acquired their meaning and therefore identity. Furthermore, this meaning- making will be demonstrated always to be situational and relational in the sense that the meaning of past material is a historical product created by strategic historic agents through their contemporary acts of identification and, as situated historical products, they are always under scrutiny and constant re-fabrication by yet other historical agents who are on the scene with yet other goals. It will also be evident throughout this study that meanings (identities) do not transcend time and space, and neither do they hide deep in the core of material artifacts awaiting to be discovered. The Introduction lays the theoretical and methodological framework of the study, situating its historiographical and sociological interests in the study of identities and the past, arguing for an approach that looks at the processes and techniques by which material and immaterial artifacts acquire their meaning. In Chapter 1 I look at scholarly interpretations as an operational act of identification; by the use of such anachronisms (which are inevitable when we study the past) as the term religion and the idea of the individual self, a certain widely-shared, and thoroughly modern understanding of Euripides’ play Hippolytus was made possible. -

New and Old Panathenaic Victor Lists

NEW AND OLD PANATHENAIC VICTOR LISTS (PLATES71-76) I. THE NEW PANATHENAIC VICTOR LISTS FINDSPOT, DESCRIPTION, AND TEXT The present inscription (pp. 188-189) listing athletic victors in the Panathenaia first came to my attention a number of years ago by word of mouth.1 I do not have accurate information about its initial discovery. The stone was initially under the jurisdiction of Dr. George Dontas, who helped me gain accessto it and determinethat no one was working on it. My own interest in the inscriptionin the first place stemmedfrom the hand. With the assistance of the Greek authorities, especially the two (former) directorsof the Akropolis, G. Dontas and E. Touloupa, whose generous cooperationI gratefully acknowledge,I have been granted permission to publish this important inscription.2In October of 1989 I was able to study the text in situ and also to make a squeeze and photographs.3 I In a joint article it is particularly important to indicate who did what. In this case Stephen Tracy has primary responsibilityfor section I, Christian Habicht for section II, and both authors for IV; section III is subdividedinto parts A, B, and C: Tracy is the primary author of A and B and Habicht of C. Nevertheless, this article is the product of close collaboration.Although initially we worked independently,each of us has read and commentedon the other's work. The final draft representsa version agreed upon by both authors. Photographs:Pls. 71-75, SVT; P1. 76, Tameion ArcheologikonPoron. All dates are B.C., unless otherwise stated. Works frequently cited are abbreviatedas follows: Agora XV = B. -

Sogdiana During the Hellenistic Period by Gurtej Jassar B.Sc, Th

Hellas Eschate The Interactions of Greek and non-Greek Populations in Bactria- Sogdiana during the Hellenistic Period by Gurtej Jassar B.Sc, The University of British Columbia, 1992 B.A.(Hon.), The University of British Columbia, 1995 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Classical, Near Eastern, and Religious Studies) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 1997 ©Gurtej Jassar, 1997 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of OA,S5J The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada DE-6 (2/88) II ABSTRACT This study deals with the syncretism between Greek and non-Greek peoples as evidenced by their architectural, artistic, literary and epigraphic remains. The sites under investigation were in the eastern part of the Greek world, particularly Ai Khanoum, Takht-i-Sangin, Dilberdjin, and Kandahar. The reason behind syncretism was discussed in the introduction, which included the persistence of the ancient traditions in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Bactria even after being conquered by the Greeks. -

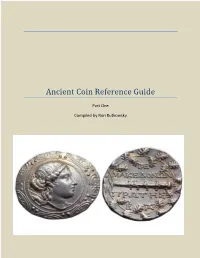

Ancient Coin Reference Guide

Ancient Coin Reference Guide Part One Compiled by Ron Rutkowsky When I first began collecting ancient coins I started to put together a guide which would help me to identify them and to learn more about their history. Over the years this has developed into several notebooks filled with what I felt would be useful information. My plan now is to make all this information available to other collectors of ancient coinage. I cannot claim any credit for this information; it has all come from many sources including the internet. Throughout this reference I use the old era terms of BC (Before Christ) and AD (Anno Domni, year of our Lord) rather than the more politically correct BCE (Before the Christian era) and CE (Christian era). Rome With most collections, there must be a starting point. Mine was with Roman coinage. The history of Rome is a subject that we all learned about in school. From Julius Caesar, Marc Anthony, to Constantine the Great and the fall of the empire in the late 5th century AD. Rome first came into being around the year 753 BC, when it was ruled under noble families that descended from the Etruscans. During those early days, it was ruled by kings. Later the Republic ruled by a Senate headed by a Consul whose term of office was one year replaced the kingdom. The Senate lasted until Julius Caesar took over as a dictator in 47 BC and was murdered on March 15, 44 BC. I will skip over the years until 27 BC when Octavian (Augustus) ended the Republic and the Roman Empire was formed making him the first emperor. -

An Analysis on Indo-Greek Period Numismatics and Acculturation

i THE SO-CALLED HELLINZATION OF GANDHARA: AN ANALYSIS ON INDO-GREEK PERIOD NUMISMATICS AND ACCULTURATION _____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Comparative and Cultural Studies At the University of Houston _____________________________________ By Franklin Todd Alexander August 2017 ii THE SO-CALLED HELLINZATION OF GANDHARA: AN ANALYSIS ON INDO-GREEK PERIOD NUMISMATICS AND ACCULTURATION ________________________________ Franklin T. Alexander APPROVED: ________________________________ Raymond Bentley, Ph.D. Committee Chair _________________________________ Randolph Widmer, Ph.D. ________________________________ Frank Holt, Ph.D. _________________________________ Anjali Kanojia, Ph.D. _________________________________ Antonio D. Tillis, Ph.D. Dean, College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences Department of Hispanic Studies iii ACKNOWLEDGMENT I would firstly like to acknowledge my family, especially my parents, who have always supported me in my endeavors. I would also like to thank my previous professors, and teachers, as without their support, I simply would not have been able to write this. Lastly, I would like to thank my four committee members who pushed me during these past two years of my life. I owe much, and more, to my chair Dr. Bentley, who not only aided me on my thesis research but also, in many ways, served as a lamp unto my feet on the uncharted path of my research. For my current knowledge of the anthropological discipline, I owe a great deal to Dr. Widmer; who would spend countless hours talking to me about the particular perspectives that pertained to my research. Dr. Widmer’s influence became particularly crucial in the resolution of this study’s methodology, and its wider potential to the anthropological discipline. -

Newsletter No. 158 Winter 1998/99 Early 17Th Century Ottoman North Africa

Other News coins and banknotes. The coin auction included a set of gold dinars of the Umayyads comprising 55 coins from AH 78 to AH 132. Johann Gustav Stickel, one of the founders of Islamic Among the Umayyad silver coins were two extremely rare dirhams Numismatics honoured from the mints of Dasht-i-Maysan and Bahurasir. by Stefan Heidemann For further information please contact Sotheby's Press Office Johann Gustav Stickel (1805 - 1896) was one of the founders of by telephone: ++44 171 293 5169; fax: ++44 171 293 5947 or Islamic Numismatics. He received his philological education in Internet: http://www.sothebys.com Jena and Paris. He studied with the venerable orientalist A. The auction held by Sotheby's of New York on 19 December Silvestre de Sacy (1758-1838), who worked in his philological included 30 lots of Islamic coins. The inclusion of such material in studies with papyri and coins as well. Stickel traced his initial the New York sales may become a regular feature. For further interest -

A Critical Study of the Schism, Origin and Formation of Sects and Sectarianism in Early Buddhis

SAṀGHABHEDA AND NIKĀYABHEDA: A CRITICAL STUDY OF THE SCHISM, ORIGIN AND FORMATION OF SECTS AND SECTARIANISM IN EARLY BUDDHISM A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Religious Studies University of the West In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By Lokānanda C. Bhikkhu Spring 2016 APPROVAL PAGE FOR GRADUATE Approved and recommended for acceptance as a dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Religious Studies. Lokānanda C. Bhikkhu, Candidate 08/09/2016 Saṁghabheda and Nikāyabheda: A Critical Study of the Schism, Origin and Formation of Sects and Sectarianism in Early Buddhism APPROVED: Joshua Capitanio, Chair 5/5/16 Jane N. Iwamura, Committee Member 5/5/16 Miroj Shakya, Committee Member 5/5/16 I hereby declare that this dissertation has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at any other institution, and that it is entirely my own work. © 2016 Lokānanda C. Bhikkhu ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I have consulted and utilized many scholarly works by various scholars, alive or dead, to whom I am under endless debt. I have no possible means to repay my debt to them, with the exception of mere acknowledgement and gratitude, which is due here: thank you all. While in school, a number of people have helped me in my progress; unfortunately, I cannot mention all of theirs names here, but I must name a few. I must, with due respect, remember the late Dr. Kenneth Locke, who very kindly admitted me into the program. Dr. -

Catalogue of Coins in the Punjab Museum, Lahore

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/catalogueofcoins01lahoiala CATALOGUE OF COINS IN THE PANJAB MUSEUM, LAHORE BY R. B. WHITEHEAD INDIAN CIVIL SERVICE, MEMBER OF THE ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY AND OF THE ASIATIC SOCIETY OF BENGAL VOL. I INDO-GREEK COINS PUBLISHED FOR THE PANJAB GOVERNMENT OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS 1914 OXFOED UNIVEKSITY PEESS LONDON EDINBUEGH GLASGOW NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE BOMBAY HUMPHEEY MILFOED M.A. PUBLISHEB TO THE UHIVEBSITY stack Annex CI U3 V. PKEFACE This volume describes the Collection of Indo-Greek coins in the Lahore Museum, Panjab, India. I have applied the term Indo-Greek to the issues of the Greek Kings of Bactria and India, and of their contemporaries and immediate successors in North-West India, who struck money bearing legible Greek inscriptions. These were the Indo-Scythic and Indo-Parthian dynasties, and the Great Kushans, down to and including Vasu Deva.^ The coins in the Lahore Museum were contained in two separate Collections. One was the Government Collection proper, and the other was the Cabinet of Mr. C. J. Rodgers, a well-known figure in Indian numismatics, a Collection which was purchased by the Panjab Government. Mr. Rodgers prepared Catalogues under official auspices, both of the Government Collection and of his own Cabinet ; and these were printed at the Baptist Mission Press, Calcutta, in the years 1892 to 1894. Neither work was illustrated, a fact which has detracted much from their value. In the Preface to one of the Parts of his Catalogue, Mr. -

10187.Ch01.Pdf

© 2006 UC Regents Buy this book Published with the support of the Classics Fund of the University of Cincinnati, established by Louise Taft Semple in memory of her father, Charles Phelps Taft. University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2006 by The Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cohen, Getzel M. The Hellenistic settlements in Syria, the Red Sea Basin, and North Africa / Getzel M. Cohen. p. cm. — (Hellenistic culture and society ; 46) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn-13: 978-0-520-24148-0 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-520-24148-7 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Cities and towns, Ancient—Syria. 2. Cities and towns, Ancient—Red Sea Region. 3. Cities and towns, Ancient—Africa, North. 4. Syria—History—333 b.c.–634 a.d. 5. Africa, North—History—To 647. 6. Red Sea Region—History. 7. Greece—Colonies—History. I. Title. II. Series. ds96.2c62 2006 930'.0971238—dc22 2005015751 Manufactured in the United States of America 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 10987654321 This book is printed on New Leaf EcoBook 60, containing 60% post-consumer waste, processed chlorine free, 30% de-inked recycled fiber, elemental chlorine free, and 10% FSC certified virgin fiber, totally chlorine free. -

Duke University Dissertation Template

Military Institutions and State Formation in the Hellenistic Kingdoms by Paul Andrew Johstono Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Joshua Sosin, Supervisor ___________________________ Alex Roland ___________________________ Kristen Neuschel ___________________________ Wayne Lee Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 i v ABSTRACT Military Institutions and State Formation in the Hellenistic Kingdoms by Paul Andrew Johstono Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Joshua Sosin, Supervisor ___________________________ Alex Roland ___________________________ Kristen Neuschel ___________________________ Wayne Lee An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 i v Copyright by Paul Andrew Johstono 2012 Abstract This dissertation examines the history of the military institutions of the Hellenistic kingdoms. The kingdoms emerged after years of war-fighting, and the capacity to wage war remained central to state formation in the Hellenistic Age (323-31 B.C.). The creation of institutions and recruitment of populations sufficient to field large armies took a great deal more time and continual effort than has generally been imagined. By bringing documentary evidence into contact with the meta-narratives of the Hellenistic period, and by addressing each of the major powers of the Hellenistic world, this project demonstrates the contingencies and complexities within the kingdoms and their armies. In so doing, it offers both a fresh perspective on the peoples and polities that inhabited the Hellenistic world after Alexander and a much-revised narrative of the process by which Alexander’s successors built kingdoms and waged war. -

More Than Men, Less Than Gods

STUDIA HELLENISTICA 51 MORE THAN MEN, LESS THAN GODS STUDIES ON ROYAL CULT AND IMPERIAL WORSHIP PROCEEDINGS OF THE INTERNATIONAL COLLOQUIUM ORGANIZED BY THE BELGIAN SCHOOL AT ATHENS (NOVEMBER 1-2, 2007) edited by Panagiotis P. IOSSIF, Andrzej S. CHANKOWSKI and Catharine C. LORBER PEETERS LEUVEN - PARIS - WALPOLE, MA 2011 993846_StHellenistica_51_VW.indd3846_StHellenistica_51_VW.indd IIIIII 33/11/11/11/11 009:579:57 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface . IX List of Contributors . XI List of Abbreviations. XIII INTRODUCTION Le culte des souverains aux époques hellénistique et impériale dans la partie orientale du monde méditerranéen: questions actuelles. 1 Andrzej S. CHANKOWSKI I. THE PRE-HELLENISTIC DIVINE KINGSHIP By the Favor of Auramazda: Kingship and the Divine in the Early Achaemenid Period. 15 Mark B. GARRISON Identities of the Indigenous Coinages of Palestine under Achae- menid Rule: the Dissemination of the Image of the Great King . 105 Haim GITLER La contribution des Teucrides aux cultes royaux de l’époque hellé- nistique . 121 Claude BAURAIN II. THE HELLENISTIC PERIOD: ROYAL CULT AND DIVINE KINGSHIP The Ithyphallic Hymn for Demetrios Poliorketes and Hellenistic Religious Mentality. 157 Angelos CHANIOTIS Never Mind the Bullocks: Taurine Imagery as a Multicultural Expression of Royal and Divine Power under Seleukos I Nikator. 197 Oliver D. HOOVER 993846_StHellenistica_51_VW.indd3846_StHellenistica_51_VW.indd V 33/11/11/11/11 009:579:57 VI TABLE OF CONTENTS Apollo Toxotes and the Seleukids: Comme un air de famille . 229 Panagiotis P. IOSSIF Theos Aigiochos: the Aegis in Ptolemaic Portraits of Divine Rulers 293 Catharine C. LORBER Ptolémée III et Bérénice II, divinités cosmiques . 357 Hans HAUBEN The Iconography of Assimilation.