Chapter 3 Figure 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pacific Flying Foxes (Mammalia, Chiroptera) : Two New Species of Pteropus from Samoa, Probably Extinct

A tamerican museum Novitates PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10024 Number 3646, 37 pp., 14 figures, 5 tables June 25, 2009 Pacific Flying Foxes (Mammalia: Chiroptera): Two New Species of Pteropus from Samoa, Probably Extinct KRISTOFER M. HELGEN,1 LAUREN E. HELGEN,2 AND DON E. WILSON3 ABSTRACT Two new species of flying foxes (genus Pteropus) from the Samoan archipelago are described on the basis of modern museum specimens collected in the mid-19th century. A medium-sized species (P. allenorum, n. sp.) is introduced from the island of Upolu (Independent Samoa), based on a specimen collected in 1856 and deposited in the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. It has not been collected again, and we regard it as almost certainly extinct. This species is smaller bodied and has much smaller teeth than both extant congeners recorded in the contemporary fauna of Samoa (Pteropus samoensis and P. tonganus). The closest relative of this new species may be Pteropus fundatus of northern Vanuatu. The disjunct historical distribution of these two small¬ toothed flying foxes (in Vanuatu and Samoa) suggests that similar species may have been more extensively distributed in the remote Pacific in the recent past. Another species, a very large flying fox with large teeth (P. coxi, n. sp.), is described from two skulls collected in Samoa in 1839-1841 during the U.S. Exploring Expedition; it too has not been collected since. This robust species resembles Pteropus samoensis and Pteropus anetianus of Vanuatu in craniodental conformation but is larger than other Polynesian Pteropus, and in some features it is ecomorphologically convergent on the Pacific monkey-faced bats (the pteropodid genera Pteralopex and Mirimiri). -

Checklist of the Mammals of Indonesia

CHECKLIST OF THE MAMMALS OF INDONESIA Scientific, English, Indonesia Name and Distribution Area Table in Indonesia Including CITES, IUCN and Indonesian Category for Conservation i ii CHECKLIST OF THE MAMMALS OF INDONESIA Scientific, English, Indonesia Name and Distribution Area Table in Indonesia Including CITES, IUCN and Indonesian Category for Conservation By Ibnu Maryanto Maharadatunkamsi Anang Setiawan Achmadi Sigit Wiantoro Eko Sulistyadi Masaaki Yoneda Agustinus Suyanto Jito Sugardjito RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY INDONESIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCES (LIPI) iii © 2019 RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY, INDONESIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCES (LIPI) Cataloging in Publication Data. CHECKLIST OF THE MAMMALS OF INDONESIA: Scientific, English, Indonesia Name and Distribution Area Table in Indonesia Including CITES, IUCN and Indonesian Category for Conservation/ Ibnu Maryanto, Maharadatunkamsi, Anang Setiawan Achmadi, Sigit Wiantoro, Eko Sulistyadi, Masaaki Yoneda, Agustinus Suyanto, & Jito Sugardjito. ix+ 66 pp; 21 x 29,7 cm ISBN: 978-979-579-108-9 1. Checklist of mammals 2. Indonesia Cover Desain : Eko Harsono Photo : I. Maryanto Third Edition : December 2019 Published by: RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY, INDONESIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCES (LIPI). Jl Raya Jakarta-Bogor, Km 46, Cibinong, Bogor, Jawa Barat 16911 Telp: 021-87907604/87907636; Fax: 021-87907612 Email: [email protected] . iv PREFACE TO THIRD EDITION This book is a third edition of checklist of the Mammals of Indonesia. The new edition provides remarkable information in several ways compare to the first and second editions, the remarks column contain the abbreviation of the specific island distributions, synonym and specific location. Thus, in this edition we are also corrected the distribution of some species including some new additional species in accordance with the discovery of new species in Indonesia. -

Ecological Assessments in the B+WISER Sites

Ecological Assessments in the B+WISER Sites (Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park, Upper Marikina-Kaliwa Forest Reserve, Bago River Watershed and Forest Reserve, Naujan Lake National Park and Subwatersheds, Mt. Kitanglad Range Natural Park and Mt. Apo Natural Park) Philippines Biodiversity & Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy & Ecosystem Resilience (B+WISER) 23 March 2015 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. The Biodiversity and Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy and Ecosystem Resilience Program is funded by the USAID, Contract No. AID-492-C-13-00002 and implemented by Chemonics International in association with: Fauna and Flora International (FFI) Haribon Foundation World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF) The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Ecological Assessments in the B+WISER Sites Philippines Biodiversity and Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy and Ecosystem Resilience (B+WISER) Program Implemented with: Department of Environment and Natural Resources Other National Government Agencies Local Government Units and Agencies Supported by: United States Agency for International Development Contract No.: AID-492-C-13-00002 Managed by: Chemonics International Inc. in partnership with Fauna and Flora International (FFI) Haribon Foundation World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF) 23 March -

Local and Landscape Compositions Influence Stingless Bee Communities and Pollination Networks in Tropical Mixed Fruit Orchards

diversity Article Local and Landscape Compositions Influence Stingless Bee Communities and Pollination Networks in Tropical Mixed Fruit Orchards, Thailand Kanuengnit Wayo 1 , Tuanjit Sritongchuay 2 , Bajaree Chuttong 3, Korrawat Attasopa 3 and Sara Bumrungsri 1,* 1 Department of Biology, Division of Biological Science, Faculty of Science, Prince of Songkla University, Hat Yai, Songkhla 90110, Thailand; [email protected] 2 Center for Integrative Conservation, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Menglun, Mengla 666303, China; [email protected] 3 Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology, Faculty of Agriculture, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand; [email protected] (B.C.); [email protected] (K.A.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +66-7428-8537 Received: 31 October 2020; Accepted: 15 December 2020; Published: 17 December 2020 Abstract: Stingless bees are vital pollinators for both wild and crop plants, yet their communities have been affected and altered by anthropogenic land-use change. Additionally, few studies have directly addressed the consequences of land-use change for meliponines, and knowledge on how their communities change across gradients in surrounding landscape cover remains scarce. Here, we examine both how local and landscape-level compositions as well as forest proximity affect both meliponine species richness and abundance together with pollination networks across 30 mixed fruit orchards in Southern Thailand. The results reveal that most landscape-level factors significantly influenced both stingless bee richness and abundance. Surrounding forest cover has a strong positive direct effect on both factors, while agricultural and urbanized cover generally reduced both bee abundance and diversity. In the local habitat, there is a significant interaction between orchard size and floral richness with stingless bee richness. -

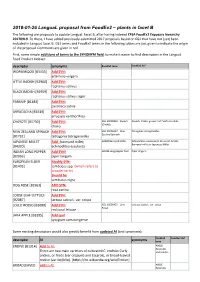

2018-01-26 Langual Proposal from Foodex2 – Plants in Facet B

2018-01-26 LanguaL proposal from FoodEx2 – plants in facet B The following are proposals to update LanguaL Facet B, after having indexed EFSA FoodEx2 Exposure hierarchy 20170919. To these, I have added previously-submitted 2017 proposals based on GS1 that have not (yet) been included in LanguaL facet B. GS1 terms and FoodEx2 terms in the following tables are just given to indicate the origin of the proposal. Comments are given in red. First, some simple additions of terms to the SYNONYM field, to make it easier to find descriptors in the LanguaL Food Product Indexer: descriptor synonyms FoodEx2 term FoodEx2 def WORMWOOD [B3433] Add SYN: artemisia vulgaris LITTLE RADISH [B2960] Add SYN: raphanus sativus BLACK RADISH [B2959] Add SYN: raphanus sativus niger PARSNIP [B1483] Add SYN: pastinaca sativa ARRACACHA [B3439] Add SYN: arracacia xanthorrhiza CHAYOTE [B1730] Add SYN: GS1 10006356 - Squash Squash, Choko, grown from Sechium edule (Choko) choko NEW ZEALAND SPINACH Add SYN: GS1 10006427 - New- Tetragonia tetragonoides Zealand Spinach [B1732] tetragonia tetragonoides JAPANESE MILLET Add : barnyard millet; A000Z Barnyard millet Echinochloa esculenta (A. Braun) H. Scholz, Barnyard millet or Japanese Millet. [B4320] echinochloa esculenta INDIAN LONG PEPPER Add SYN! A019B Long pepper fruit Piper longum [B2956] piper longum EUROPEAN ELDER Modify SYN: [B1403] sambucus spp. (which refers to broader term) Should be sambucus nigra DOG ROSE [B2961] ADD SYN: rosa canina LOOSE LEAF LETTUCE Add SYN: [B2087] lactusa sativa L. var. crispa LOLLO ROSSO [B2088] Add SYN: GS1 10006425 - Lollo Lactuca sativa L. var. crispa Rosso red coral lettuce JAVA APPLE [B3395] Add syn! syzygium samarangense Some existing descriptors would also greatly benefit from updated AI (and synonyms): FoodEx2 FoodEx2 def descriptor AI synonyms term ENDIVE [B1314] Add to AI: A00LD Escaroles There are two main varieties of cultivated C. -

Study on Measurement and Determination Carbon Pool in Traditional Agroforestry System for Handling Climate Change

International Journal of Forestry and Horticulture (IJFH) Volume 4, Issue 2, 2018, PP 14-24 ISSN No. (Online) 2454–9487 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2454-9487.0402003 www.arcjournals.org Study on Measurement and Determination Carbon Pool in Traditional Agroforestry System for Handling Climate Change Jan Willem Hatulesila1, Cornelia M.A.Wattimena1, Ludia Siahaya1 1Forestry Department, Faculty of Agriculture, Pattimura University *Corresponding Author: Jan Willem Hatulesila, Forestry Department, Faculty of Agriculture, Pattimura University. Abstract: The forest that is the lungs of the world plays a very important role in the continuity of life on earth. Forests absorb Co2 during the process of photosynthesis and decomposition as organic matter in plant biomass. Measurement of forest productivity by biomass measurement. Forest biomass provides important information in the predicted potential of Co2 and biomass sequestration in certain ages that can be used to estimate forest productivity. This research was conducted in the community forest of Hutumuri village as one of traditional agroforestry “dusung” in Ambon Island. Beside that data base can serve as a planner base for the development of large-scale forecasts of carbon stocks for total community forest of agroforestry patterns. The carbon measurement method is done in demonstration plot for tree, sapling and forest floor level. The results show the dominant plant species for plot I in the dominance of nutmeg (Myristica fragrans), plot II durian (Durio zibethinus) and plot III duku (Lansium spp). The total measured biomass on tree vegetation was 58.52 tC / ha; forest floor was 1.71 tC / ha; top soil layer was 13 tC / ha, woody necromass was 33.56 kg 2 / m ; rough and soft litter were 1.84 tC / ha, necromass was 67.16 tC / ha. -

Species-Edition-Melanesian-Geo.Pdf

Nature Melanesian www.melanesiangeo.com Geo Tranquility 6 14 18 24 34 66 72 74 82 6 Herping the final frontier 42 Seahabitats and dugongs in the Lau Lagoon 10 Community-based response to protecting biodiversity in East 46 Herping the sunset islands Kwaio, Solomon Islands 50 Freshwater secrets Ocean 14 Leatherback turtle community monitoring 54 Freshwater hidden treasures 18 Monkey-faced bats and flying foxes 58 Choiseul Island: A biogeographic in the Western Solomon Islands stepping-stone for reptiles and amphibians of the Solomon Islands 22 The diversity and resilience of flying foxes to logging 64 Conservation Development 24 Feasibility studies for conserving 66 Chasing clouds Santa Cruz Ground-dove 72 Tetepare’s turtle rodeo and their 26 Network Building: Building a conservation effort network to meet local and national development aspirations in 74 Secrets of Tetepare Culture Western Province 76 Understanding plant & kastom 28 Local rangers undergo legal knowledge on Tetepare training 78 Grassroots approach to Marine 30 Propagation techniques for Tubi Management 34 Phantoms of the forest 82 Conservation in Solomon Islands: acts without actions 38 Choiseul Island: Protecting Mt Cover page The newly discovered Vangunu Maetambe to Kolombangara River Island endemic rat, Uromys vika. Image watershed credit: Velizar Simeonovski, Field Museum. wildernesssolomons.com WWW.MELANESIANGEO.COM | 3 Melanesian EDITORS NOTE Geo PRODUCTION TEAM Government Of Founder/Editor: Patrick Pikacha of the priority species listed in the Critical Ecosystem [email protected] Solomon Islands Hails Partnership Fund’s investment strategy for the East Assistant editor: Tamara Osborne Melanesian Islands. [email protected] Barana Community The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) Contributing editor: David Boseto [email protected] is designed to safeguard Earth’s most biologically rich Prepress layout: Patrick Pikacha Nature Park Initiative and threatened regions, known as biodiversity hotspots. -

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats

Index of Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol. 9. Bats A agnella, Kerivoula 901 Anchieta’s Bat 814 aquilus, Glischropus 763 Aba Leaf-nosed Bat 247 aladdin, Pipistrellus pipistrellus 771 Anchieta’s Broad-faced Fruit Bat 94 aquilus, Platyrrhinus 567 Aba Roundleaf Bat 247 alascensis, Myotis lucifugus 927 Anchieta’s Pipistrelle 814 Arabian Barbastelle 861 abae, Hipposideros 247 alaschanicus, Hypsugo 810 anchietae, Plerotes 94 Arabian Horseshoe Bat 296 abae, Rhinolophus fumigatus 290 Alashanian Pipistrelle 810 ancricola, Myotis 957 Arabian Mouse-tailed Bat 164, 170, 176 abbotti, Myotis hasseltii 970 alba, Ectophylla 466, 480, 569 Andaman Horseshoe Bat 314 Arabian Pipistrelle 810 abditum, Megaderma spasma 191 albatus, Myopterus daubentonii 663 Andaman Intermediate Horseshoe Arabian Trident Bat 229 Abo Bat 725, 832 Alberico’s Broad-nosed Bat 565 Bat 321 Arabian Trident Leaf-nosed Bat 229 Abo Butterfly Bat 725, 832 albericoi, Platyrrhinus 565 andamanensis, Rhinolophus 321 arabica, Asellia 229 abramus, Pipistrellus 777 albescens, Myotis 940 Andean Fruit Bat 547 arabicus, Hypsugo 810 abrasus, Cynomops 604, 640 albicollis, Megaerops 64 Andersen’s Bare-backed Fruit Bat 109 arabicus, Rousettus aegyptiacus 87 Abruzzi’s Wrinkle-lipped Bat 645 albipinnis, Taphozous longimanus 353 Andersen’s Flying Fox 158 arabium, Rhinopoma cystops 176 Abyssinian Horseshoe Bat 290 albiventer, Nyctimene 36, 118 Andersen’s Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arafura Large-footed Bat 969 Acerodon albiventris, Noctilio 405, 411 Andersen’s Leaf-nosed Bat 254 Arata Yellow-shouldered Bat 543 Sulawesi 134 albofuscus, Scotoecus 762 Andersen’s Little Fruit-eating Bat 578 Arata-Thomas Yellow-shouldered Talaud 134 alboguttata, Glauconycteris 833 Andersen’s Naked-backed Fruit Bat 109 Bat 543 Acerodon 134 albus, Diclidurus 339, 367 Andersen’s Roundleaf Bat 254 aratathomasi, Sturnira 543 Acerodon mackloti (see A. -

Lepidoptera, Cossidae) from Indonesia and Thailand

Ecologica Montenegrina 38: 102-106 (2020) This journal is available online at: www.biotaxa.org/em http://dx.doi.org/10.37828/em.2020.38.12 https://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:05A73DF2-AC30-4CDD-A01E-E1999D5B1A3D Two new species of Roepkiella Yakovlev & Witt, 2009 (Lepidoptera, Cossidae) from Indonesia and Thailand ROMAN V. YAKOVLEV Altai State University, pr. Lenina 61, Barnaul, 656049, Russia. E-mail: [email protected] Tomsk State University, Laboratory of Biodiversity and Ecology, Lenina pr. 36, 634050 Tomsk, Russia Received 21 November 2020 │ Accepted by V. Pešić: 9 December 2020 │ Published online 10 December 2020. Abstract The article describes two new species: Roepkiella jakli sp. nov. (type locality: Indonesia, Sangir Isl., Tahuna Distr., Bukit Bembalut Hill) and R. korshunovi sp. nov. (type locality: Thailand, Khon Kaen Prov., Phu Wiang Wat). The diagnostic features are given, the male genitalia of R. celebensis (Roepke, 1957) are described for the first time. Key words: biodiversity, Cossoidea, entomology, Asia, Paleotropics, Oriental Region, taxonomy, new species. Introduction The genus Roepkiella Yakovlev & Witt, 2009 (Lepidoptera, Cossidae) was firstly described for Cossus rufidorsia Hampson, 1904 (type locality: Sikhim [E. India, Sikkim prov.]) by original designation (Yakovlev & Witt 2009). According to the publications (Roepke 1957; Arora 1976; Holloway 1986; Schoorl 1990; Yakovlev 2011, 2014) the genus includes 14 species, distributed in Hindustan, Indochina, Myanmar, Malacca, Borneo, Java, Sumatra, and Sulawesi. Their biology is very poorly studied. Only for R. chlorata (Swinhoe, 1892) (type locality: Sarawak, Borneo) and Roepkiella subfusca (Snellen, 1895) (type locality: [Deli, Ost Sumatra]) the feed plants were indicated: Intsia palembanica Miquel, 1861, Parkia sp. -

A Re-Evaluation of Allometric Relationships for Circulating Concentrations of Glucose in Mammals

Food and Nutrition Sciences, 2016, 7, 240-251 Published Online April 2016 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/fns http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/fns.2016.74026 A Re-Evaluation of Allometric Relationships for Circulating Concentrations of Glucose in Mammals Colin G. Scanes Department of Biological Science, University of Wisconsin Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI, USA Received 10 August 2015; accepted 19 April 2016; published 22 April 2016 Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Purpose: The present study examined the putative relationship between circulating concentra- tions of glucose and log10 body weight in a large sample size (270) of wild species but with domes- ticated animals excluded from the analyses. Methods: A data-set of plasma/serum concentration of glucose and body weight in mammalian species was developed from the literature. Allometric re- lationships were examined. Results: In contrast to previous reports, no overall relationship for circulating concentrations of glucose was observed across 270 species of mammals (for log10 glu- cose concentration adjusted R2 = −0.003; for glucose concentration adjusted R2 = −0.003). In con- trast, a strong allometric relationship was observed for circulating concentrations of glucose in 2 Primates (for log10 glucose concentration adjusted R = 0.511; for glucose concentration adjusted R2 = 0.480). Conclusion: The absence of an allometric relationship for circulating concentrations of glucose was unexpected. A strong allometric relationship was seen in Primates. Keywords Glucose, Allometric, Mammals, Primates 1. Introduction Glucose in the blood is the principal energy source for brain functioning and but glucose can be used as the energy source for multiple other tissues. -

Report- Phase I

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT- PHASE I September 2020 DRAFT EIA REPORT Bangalore – Chennai Expressway-Phase-I TOR Compliances The following are the compliances for the ToR issued by MOEF vide letter NO.F.No. 10-15/2018- IA.III dated 14th May 2018 for the Bangalore-Chennai Expressway Phase-I. Sr. No. TOR Points & Conditions Compliances A Project Specific Conditions Quantity and Source of water utilization and its Section 4.2.3.3 of Chapter-4 i permission ii Traffic density study to be carried out. Section 2.7.3 of Chapter-2 Cumulative impact assessment study to be carried Refer Section 4.5 of Chapter 4 iii out along proposed alignment including other packages. Detailed Impact assessment study to be carried out Chapter-4 and Chapter-9 iv with mitigation measures for protection of reservoirs, water bodies and rivers if any Composite plan to compensate the loss of tree cover Annexure-9.1 of Chapter-9 v though massive tree plantation programme with time schedule and financial outlay B General Conditions A brief description of the project, project name, Chapter-1 & Chapter-2 i nature, size, its importance to the region/state and the country shall be submitted In case the project involves diversion of forests No forest Land diversion land, guidelines under OM dated 20.03.2013 shall ii be followed and necessary action be taken accordingly Details of any litigation(s) pending against the No litigations are pending against project and/or any directions or orders passed by the project road iii any court of law/any statutory authority against the project to be detailed out. -

Table S1 Wild Food Plants Used by Minangkabau and Mandailing Women in Pasaman Regency, West Sumatra, Indonesia

Table S1 Wild food plants used by Minangkabau and Mandailing women in Pasaman regency, West Sumatra, Indonesia Plant species and Plant family Local names Local food Part used and Cited by % of Habitat voucher number category extent of use respondents Food group: Starchy staples Manihot esculenta C Euphorbiaceae Ubi singkong, Ubi Staple Tuber 74 (30 Ma; 44 Mi) Ag, Ho, rantz kayu (Mi, Ma) food/snack ++ Fi Colocasia esculenta ( Araceae Talas (Mi); Suhat Staple Tuber 53 (16 Ma; 37 Mi) Ae, Af, L.) Schott (LP16) (Ma) food/snack + Fi Ipomoea batatas (L.) Convolvulaceae Ubi jalar (Mi, Ma) Staple Tuber 25 (30 Ma; 44 Mi) Fi, Hg Poir. food/snack + Xanthosoma Araceae Talas hitam (Mi) Staple Tuber 1 (0 Ma; 1 Mi) Af sagittifolium (L.) food/snack - Schott (LP56) Food group: Pulses Archidendron Leguminosae Jariang (Mi); Joring Vegetable Seed 14 (4 Ma; 10 Mi) Af pauciflorum (Benth.) (Ma); Jengkol (Mi, ++++ I.C.Nielsen Ma) Parkia speciosa Leguminosae Petai (Mi, Ma) Vegetable Seed 7 (4 Ma; 3 Mi) Af Hassk. ++++ Archidendron Leguminosae Kabau, Sikabau Vegetable Seed 3 (0 Ma; 3 Mi) Af bubalinum (Jack) (Mi); Kaladeh (Ma) ++ I.C.Nielsen Parkia speciosa Leguminosae Potar, Parira, Petai Vegetable Seed 1 (1 Ma; 0 Mi) Af, Fo Hassk. (LP17) hutan (Ma) + Species not Leguminosae Kacang tujuh Vegetable/ Seed 0 (0 Ma; 1 Mi) Af, Fi identified (LP41) lembar daun (Mi) bean + Vigna unguiculata Leguminosae Kacang tunjuk (Mi, Vegetable/ Seed Only FGD (Mi, Ma) Fi, Hg 'kacang tunjuk' Ma) bean - (LP35) Food group: Nuts and Seeds Artocarpus sp. Moraceae Nankga hutan (Mi); Vegetable Fruit (unripe) 13 (3 Ma; 10 Mi) Fo Nangka/Sibodak + rimbo (Ma) Pangium edule Achariaceae Siwamang (Mi); Fruit Seed 2 (0 Ma; 2 Mi) Af Reinw.