Jazz Italiano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Il Jazz Appreciation Month Di Aprile 2017

Gentili lettori, questa nostra introduzione, del Club per l’UNESCO di Livorno, è semplicemente per spiegarvi in poche parole il perché di tale piccolo quaderno scritto appositamente per il mese dedicato al Jazz, ovvero il Jazz Appreciation Month di Aprile 2017. Abbiamo cooperato alla pubblicazione di questo semplice libriccino sul Jazz unicamente perché innanzitutto è un genere che ha rapidamente conquistato tutto il mondo e tutti gli strati sociali, poi perché questo bel ritmo ha qualcosa di trascinante e di affascinante che smuove quell'elettricità che tutti abbiamo nella testa e nel cuore. Chi di noi non ha mai mosso un piede nel sentirla, questa musica galvanizzante? Inoltre Livorno, anche perché geograficamente vicinissima ad una base americana, da tempo ne è stata contagiata dato che proprio in America è nato, nei bui locali e nelle fumose sale della vecchia New York e altre città, questo modo di interpretare i sentimenti. Godetevi quindi questa breve lettura che speriamo, come Club per l’UNESCO di Livorno, vi piaccia. Un grazie a Andrea Pellegrini, all’architetto Chiara Carboni e alla Vice Presidente del Club Rossella Bruni Chelini. Margherita Mazzelli Presidente Club per l’UNESCO Livorno a Alberto Granucci 100 anni fa: il Jazz Cento anni fa una forma musicale nuova (un “suono nuovo” come fu definito da Louis Amstrong) che già da qualche anno aveva incominciato a pervadere i locali e le strade di alcune città del sud degli Stati Uniti fu per la prima volta “incisa” su un vinile. Da quel momento, da quel primo disco a 78 giri, il Jazz è divenuto la colonna sonora di un’epoca contrassegnata da grandi cambiamenti. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Musica, Musica, Musica

William Ghizzoni MUSICA, MUSICA, MUSICA Di tutto un po’ … Mini-corso di Musicologia II edizione Aprile 2020 Sommario Premessa ............................................................................................... 7 Il mondo della musica: una possibile classificazione ........................... 11 AREA CLASSICA .................................................................................... 15 1. Musica sinfonica ...................................................................... 16 2. Musica cameristica .................................................................. 20 3. Musica lirica (Operistica) ......................................................... 22 4. Musica Sacra ............................................................................ 25 5. Altri generi ............................................................................... 29 AREA MUSICA LEGGERA ...................................................................... 33 6. Musica da ballo (e danza) ........................................................ 34 7. Operetta (e Romanza) ............................................................. 43 8. Il "Musical" .............................................................................. 45 9. La musica da film ..................................................................... 48 10. La musica "Pop" ................................................................... 51 11. Rhythm & Blues e Soul Music .............................................. 53 12. La musica Rock.................................................................... -

Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: the Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa

STYLISTIC EVOLUTION OF JAZZ DRUMMER ED BLACKWELL: THE CULTURAL INTERSECTION OF NEW ORLEANS AND WEST AFRICA David J. Schmalenberger Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Percussion/World Music Philip Faini, Chair Russell Dean, Ph.D. David Taddie, Ph.D. Christopher Wilkinson, Ph.D. Paschal Younge, Ed.D. Division of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2000 Keywords: Jazz, Drumset, Blackwell, New Orleans Copyright 2000 David J. Schmalenberger ABSTRACT Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: The Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa David J. Schmalenberger The two primary functions of a jazz drummer are to maintain a consistent pulse and to support the soloists within the musical group. Throughout the twentieth century, jazz drummers have found creative ways to fulfill or challenge these roles. In the case of Bebop, for example, pioneers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach forged a new drumming style in the 1940’s that was markedly more independent technically, as well as more lyrical in both time-keeping and soloing. The stylistic innovations of Clarke and Roach also helped foster a new attitude: the acceptance of drummers as thoughtful, sensitive musical artists. These developments paved the way for the next generation of jazz drummers, one that would further challenge conventional musical roles in the post-Hard Bop era. One of Max Roach’s most faithful disciples was the New Orleans-born drummer Edward Joseph “Boogie” Blackwell (1929-1992). Ed Blackwell’s playing style at the beginning of his career in the late 1940’s was predominantly influenced by Bebop and the drumming vocabulary of Max Roach. -

Immigrant Musicians on the New York Jazz Scene by Ofer Gazit A

Sounds Like Home: Immigrant Musicians on the New York Jazz Scene By Ofer Gazit A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Benjamin Brinner, Chair Professor Jocelyne Guilbault Professor George Lewis Professor Scott Saul Summer 2016 Abstract Sounds Like Home: Immigrant Musicians On the New York Jazz Scene By Ofer Gazit Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Benjamin Brinner, Chair At a time of mass migration and growing xenophobia, what can we learn about the reception, incorporation, and alienation of immigrants in American society from listening to the ways they perform jazz, the ‘national music’ of their new host country? Ethnographies of contemporary migrations emphasize the palpable presence of national borders and social boundaries in the everyday life of immigrants. Ethnomusicological literature on migrant and border musics has focused primarily on the role of music in evoking a sense of home and expressing group identity and solidarity in the face of assimilation. In jazz scholarship, the articulation and crossing of genre boundaries has been tied to jazz as a symbol of national cultural identity, both in the U.S and in jazz scenes around the world. While these works cover important aspects of the relationship between nationalism, immigration and music, the role of jazz in facilitating the crossing of national borders and blurring social boundaries between immigrant and native-born musicians in the U.S. has received relatively little attention to date. -

The Avant-Garde in Jazz As Representative of Late 20Th Century American Art Music

THE AVANT-GARDE IN JAZZ AS REPRESENTATIVE OF LATE 20TH CENTURY AMERICAN ART MUSIC By LONGINEU PARSONS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2017 © 2017 Longineu Parsons To all of these great musicians who opened artistic doors for us to walk through, enjoy and spread peace to the planet. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my professors at the University of Florida for their help and encouragement in this endeavor. An extra special thanks to my mentor through this process, Dr. Paul Richards, whose forward-thinking approach to music made this possible. Dr. James P. Sain introduced me to new ways to think about composition; Scott Wilson showed me other ways of understanding jazz pedagogy. I also thank my colleagues at Florida A&M University for their encouragement and support of this endeavor, especially Dr. Kawachi Clemons and Professor Lindsey Sarjeant. I am fortunate to be able to call you friends. I also acknowledge my friends, relatives and business partners who helped convince me that I wasn’t insane for going back to school at my age. Above all, I thank my wife Joanna for her unwavering support throughout this process. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 4 LIST OF EXAMPLES ...................................................................................................... 7 ABSTRACT -

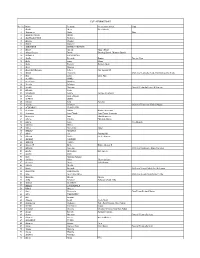

Nr. Crt Nume Prenume Pseudonim Artistic Grup 1 Abaribi Diego Diego Abaribi 2 Abatangelo Giulio Klune 3 ABATANTUONO DIEGO 4 ABATE

LISTA MEMBRI UNART Nr. Crt Nume Prenume Pseudonim Artistic Grup 1 Abaribi Diego Diego Abaribi 2 Abatangelo Giulio Klune 3 ABATANTUONO DIEGO 4 ABATEGIOVANNI FRANCA 5 Abbado Claudio 6 Abbiati Giovanni 7 ABBONDATI MANOLO CRISTIAN 8 Abbott Vincent Vinnie Abbott 9 Abbott (Estate) Darrell Dimebag Darrell, Diamond Darrell 10 ABDALLA SAID CAROLA 11 Abeille Riccardo Ronnie Dancing Crap 12 Abela Laura L'Aura 13 Abels Zachary Zachary Abels 14 Abeni Maurizio 15 Abossolo Mbossoro Fabien Sisi / Logobit Gt 16 Abriani Emanuela Orchestra Teatro alla Scala, Filarmonica della Scala 17 Abur Ioana Ioana Abur 18 ACAMPA MARIO 19 Accademia Bizantina 20 Accardo Salvatore 21 Accolla Giuseppe Coro del Teatro La Fenice di Venezia 22 Achenza Paolo 23 Achermann Jerome Jerome Achermann 24 Achiaua Andrei-Marian 25 ACHILLI GIULIA 26 Achoun Sofia Samaha 27 Acierno Salvatore Orchestra Teatro San Carlo di Napoli 28 ACQUAROLI FRANCESCO 29 Acquaviva Battista Battista Acquaviva, 30 Acquaviva Jean-Claude Jean-Claude Acquaviva 31 Acquaviva John John Acquaviva 32 Adamo Cristian Christian Adamo 33 Adamo Ivano New Disorder 34 Addabbo Matteo 35 Addea Alessandro Addal 36 ADEZIO GIULIANA 37 Adiele Eric Sporting Life 38 Adisson Gaelle Gaelle Adisson 39 ADORNI LORENZO 40 ADRIANI LAURA 41 Afanasieff Walter Walter Afanasieff 42 Affilastro Giuseppe Orchestra Fondazione Arturo Toscanini 43 Agache Alexandrina Dida Agache 44 Agache Iulian 45 Agate Girolamo Antonio 46 Agebjorn Johan Johan Agebjorn 47 Agebjorn Hanna Sally Shapiro 48 Agliardi Niccolò 49 Agosti Riccardo Orchestra Teatro Carlo -

Italian-Australian Musicians, ‘Argentino’ Tango Bands and the Australian Tango Band Era

2011 © John Whiteoak, Context 35/36 (2010/2011): 93–110. Italian-Australian Musicians, ‘Argentino’ Tango Bands and the Australian Tango Band Era John Whiteoak For more than two decades from the commencement of Italian mass migration to Australia post-World War II, Italian-Australian affinity with Hispanic music was dynamically expressed through the immense popularity of Latin-American inflected dance music within the Italian communities, and the formation of numerous ‘Italian-Latin’ bands with names like Duo Moreno, El Bajon, El Combo Tropicale, Estrellita, Mambo, Los Amigos, Los Muchachos, Mokambo, Sombrero, Tequila and so forth. For venue proprietors wanting to offer live ‘Latin- American’ music, the obvious choice was to hire an Italian band. Even today, if one attends an Italian community gala night or club dinner-dance, the first or second dance number is likely to be a cha-cha-cha, mambo, tango, or else a Latinised Italian hit song played and sung in a way that is unmistakably Italian-Latin—to a packed dance floor. This article is the fifteenth in a series of publications relating to a major monograph project, The Tango Touch: ‘Latin’ and ‘Continental’ Influences on Music and Dance before Australian ‘Multiculturalism.’1 The present article explains how the Italian affinity for Hispanic music was first manifested in Australian popular culture in the form of Italian-led ‘Argentino tango,’ ‘gaucho-tango,’ ‘Gypsy-tango,’ ‘rumba,’ ‘cosmopolitan’ or ‘all-nations’ bands, and through individual talented and entrepreneurial Italian-Australians who were noted for their expertise in Hispanic and related musics. It describes how a real or perceived Italian affinity with Hispanic and other so-called ‘tango band music’ opened a gateway to professional opportunity for various Italian-Australians, piano accordionists in particular. -

La Famiglia Canterina

Anita Camarella & Davide Facchini Duo la famiglia canterina Honored with the "LadyLake Indie Music Awards" Best Album 2013 U.S.A. Anita Camarella and Davide Facchini new album “La famiglia canterina” collects some of the greatest hits from the repertoire of Swing Italian. Draw a line of continuity in their music- historical research of early modern Italian music and is thought of as a natural evolution of their first recording, “Quei motivetti che ci piaccion tanto” (2002). This CD is full of swing, songs, quotes, curiosities, guitars, special guests. Each arrangement draws liberally from the many experiences, expertise and varied musical influences of the two artists. Just within this CD has been possible to gather after 60 years, two Italian guitarists as legendary who have experienced first hand this music: Franco Cerri (1926), a famous jazz guitarist and Raf Montrasio (1929), legendary guitarist of the legendary Renato Carosone sextet in the 50s, by which Anita Camarella and Davide Facchini have been collaborating for several years. “La famiglia canterina” (1941) is a song that carries with it many stories... It’s a tribute to the radio, whose first broadcasts reached Italy in 1924; its lyrics mention some of the most famous Italian singers, musicians and orchestras from the '30s and '40s - among them Ernesto Bonino and the Trio Lescano, original performers of this song - and hint at other songs of that era. All this is told through the story of a singing family in which the mother, father and their little daughter are racing to sing their favorite songs. For over 10 years Anita Camarella and Davide Facchini carry and tell around the world this wonderful music, a ‘fresco’ of Italian history that fascinates all generations, thanks to a show devoted to this repertoire, its performers and musicians. -

The Role of Music in European Integration Discourses on Intellectual Europe

The Role of Music in European Integration Discourses on Intellectual Europe ALLEA ALLEuropean A cademies Published on behalf of ALLEA Series Editor: Günter Stock, President of ALLEA Volume 2 The Role of Music in European Integration Conciliating Eurocentrism and Multiculturalism Edited by Albrecht Riethmüller ISBN 978-3-11-047752-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-047959-1 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-047755-9 ISSN 2364-1398 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover: www.tagul.com Typesetting: Konvertus, Haarlem Printing: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Foreword by the Series Editor There is a debate on the future of Europe that is currently in progress, and with it comes a perceived scepticism and lack of commitment towards the idea of European integration that increasingly manifests itself in politics, the media, culture and society. The question, however, remains as to what extent this report- ed scepticism truly reflects people’s opinions and feelings about Europe. We all consider it normal to cross borders within Europe, often while using the same money, as well as to take part in exchange programmes, invest in enterprises across Europe and appeal to European institutions if national regulations, for example, do not meet our expectations. -

LINER NOTES Recorded Anthology of American Music, Inc

ALL THE RAGE: New World Records 80544 Nashville Mandolin Ensemble At the turn of the twentieth century, a sound lilted through the air of American music like nothing that had ever been heard before. It inspired one writer to call it “the true soul of music.” It inspired thousands of Americans to pick up instruments and form groups to create this sound for themselves. It was the sound of the mandolin orchestra, a sound that the Nashville Mandolin Orchestra recreates on All the Rage, a sound as fresh and new today as it was in its heyday. The late nineteenth century was an exciting time for American music lovers. The invention of the phonograph had brought music into the home, and the increased exposure and competition brought out the best in musicians. John Philip Sousa’s band perfected the sound of the brass band, and the Peerless Quartet took four-part vocal performance to a level of perfection. But these were stylistic accomplishments with familiar, existing sounds—brass instruments and human vocal cords. The sound of the mandolin orchestra carried an extra edge of excitement because most Americans had never even heard a mandolin, much less the sound of mandolin-family instruments played in an orchestral setting. The mandolin alone had a distinct, unique sound. When a mandolinist plucked a single-note run, nothing could match its crispness of attack and delicacy of tone. And when a group of mandolin-family instruments launched into an ensemble tremolo, the listener was bathed in wave after wave of the most beautiful sound imaginable. -

The Jazz Tradition Jeff Rupert Thursday, June 27

Music for All Summer Symposium presented by Yamaha www.musicforall.org The Jazz Tradition Jeff Rupert Thursday, June 27 Music For All Summer Symposium SURVEY OF JAZZ HISTORY Jeff Rupert I Influences and elements of early jazz A Congo Square, New Orleans. 1 Gathering place for slaves in New Orleans, from the late 1700’s. 2 Catholicism in New Orleans. 3 Slave trade abolished in 1808. 4 Emancipation proclamation in 1862. B Ragtime 1 Scott Joplin,(1867-1917), primary composer and pianist. 2 Piano music, first published in 1896. 3 Syncopated music 4 Complex march-like song forms 5 Simulating the orchestra or marching band C Country Blues 1 Migration from the country into New Orleans. 2 Blues Inflections 3 Vocal Characteristics peculiar to the blues. 4 The first blues published in 1904. “I’ve got the blues”. 5 W.C. Handy publishes “St. Louis Blues” in 1914. D Marching bands in New Orleans 1 Several popular bands, serving numerous functions The Superior, the Onward Brass Bands playing parades, funerals and concerts. 2 Marching bands syncopating, or “ragging” rhythms 3 Playing “head charts” 4 The Big 4 5 Buddy Bolden,(1877-1931), Freddie Keppard, (1890-1933). E Opera and other European influence in New Orleans. 1 Opera and Orchestras in New Orleans 2 Creoles before and after the “black codes” or Jim Crow laws.(1877-1965). Plessy vs Ferguson upheld Jim Crow laws of separate but equal in Louisiana in 1896. 3 Music in New Orleans after the black codes. 4 Instruments incorporated in early jazz. Jazz History Outline. © Jeff Rupert RUPE MUSIC Pub.