The Desert Is Food

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Lippia Graveolens HBK) EN MAPIMÍ, DURANGO Diódoro Granados-S

ECOLOGÍA, APROVECHAMIENTO Y COMERCIALIZACIÓN DEL ORÉGANO (Lippia graveolens H. B. K.) EN MAPIMÍ, DURANGO ECOLOGY, HARVESTING AND MARKETING OF OREGANO (Lippia graveolens H. B. K.) IN MAPIMÍ, DURANGO Diódoro Granados-Sánchez1*; Martín Martínez-Salvador2; Georgina F. López-Ríos1; Amparo Borja-De la Rosa1; Gabriel A. Rodríguez-Yam1 1División de Ciencias Forestales. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. km 38.5 Carretera México-Tex- coco. C. P. 56230. Chapingo, Texcoco, Edo. de México. Correo-e: [email protected] (*Autor para correspondencia). 2Sitio experimental La Campana-Madera, Centro de Investigación Regional Norte Centro-Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales Agrícolas y Pecuarias. RESUMEN l orégano, Lippia graveolens H. B. K., es una planta adaptada a las condiciones de aridez con capacidad para prosperar bajo diversos grados de presión por la recolección. En Mapimí, Du- rango, la planta ha sido colectada y comercializada durante años y significa una fuente de ingresos para las familias que dependen de su recolección, aunque los comerciantes obtienen Ela mayor parte de los beneficios. En la región de Mapimí se evaluaron las diversas áreas productoras con el fin de establecer la dinámica e impacto del proceso de recolección y sus efectos sobre la planta. Para esto, se hicieron recorridos de campo, toma de muestras y delimitación de las áreas de distribución del orégano. También se analizó el proceso de producción y los canales de comercialización, a fin de diseñar una alternativa de manejo que garantice la sustentabilidad de la actividad. El proceso de producción PALABRAS CLAVE: Recolectores, y comercialización se estudió mediante la aplicación de entrevistas abiertas a productores, visitas de conservación, Desierto campo y visitas a las empresas beneficiadoras y comercializadoras, así como a los intermediarios que Chihuahuense, recursos naturales. -

T20672 ROSALES ALEMAN, VIVIANA 63754.Pdf

UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA AGRARIA ANTONIO NARRO DIVISIÓN DE CIENCIA ANIMAL DEPARTAMENTO DE CIENCIA Y TECNOLOGÍA DE ALIMENTOS Evaluación del efecto antioxidante y antimicrobiano de los residuos de orégano (Lippia graveolens). Por: VIVIANA ROSALES ALEMÁN TESIS Presentada como requisito parcial para obtener el título profesional de: Ingeniero en Ciencia y Tecnología de Alimentos Buenavista, Saltillo, Coahuila, México. Noviembre de 201 Dedicatorias A Dios: Por darme la oportunidad de vivir y por estar conmigo en cada paso que doy, por fortalecer mi corazón e iluminar mi mente y por haber puesto en mi camino a aquellas personas que han sido mi soporte y compañía durante todo el periodo de estudio. A mis padres: Sofía Alemán García y Santiago Rosales Montero por haberme apoyado a lo largo de mi estudio, por su comprensión, esfuerzo y apoyo incondicional; porque si no fuera por ellos no hubiera sido posible este triunfo. A mis hermanos: Israel, Esperanza, René, Julio y a mi hermano Luis que aunque ya no esté físicamente con nosotros vive por siempre en nuestro corazón, gracias por su compresión, apoyo y cariño. A mi novio: Marco Herrera por siempre estar a mi lado en las buenas y en las malas; por su comprensión, paciencia y amor, dándome ánimos de fuerza y valor para seguir a delante. A mis amigos: De la generación CXVlll de ICTA, gracias por su amistad y confianza, sinceramente deseo que donde quiera que vayan tengan una vida llena de éxitos. Agradecimientos En primer lugar quiero agradecer a Dios por haberme dado la sabiduría, el entendimiento y la fortaleza para poder llegar al final de mi carrera, por no haber dejado que me rindiera en ningún momento e iluminarme para salir adelante. -

Coastal Wetlunds of the Noytherrn Gua of Califurnia

AQUATIC CONSERVATION:MARINE AND FRESHWATERECOSYSTEMS Aquatic Conseru:Mar. Freshv. Ecosyst. l6: 5 28 (2006) Publishedonline in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com).DOI: 10.1002/aqc.68l Coastal wetlundsof the noytherrnGuA of Califurnia: inventory flnd conservutionstatus EDWARD P. GLENNO'*, PAMELA L. NAGLERU, RICHARD C. BRUSCAb and OSVEL HINOJOSA-HUERTA' " EnvironntentalResearch Laborator!-,2601 East Airport Drive, Tucson,AZ 85706, USA bAritora Sonora Desert Museum,2021 North Kinney RoacJ,Tucson, AZ 85743,USA 'Pronatura lVoroeste,Ave. Jalisco 903, Colonia Sonora, San Luis Rio Colorado, Sonora 83440. Meric'o ABSTRACT 1. Above 28"N, the coastlineof the northern Gulf of California is indented at frequent intervals by negative or inverseestuaries that are saltier at their backs than at their mouths due to the lack of freshwater inflow. These 'esteros'total over l32,ogo ha in area and encompassmangrove marshes below 29"N and saltgrass(Drsrichlis palmeri) marshes north of 29"N. An additional 6000 ha of freshwaterand brackish wetlandsare found in the Colorado River delta where fresh water entersthe intertidal zone. 2. The mangrove marshesin the Gulf of California have been afforded some degreeof protected statusin Mexico, but the northern saltgrassesteros do not have priority conservationstatus and are increasinglybecoming developmenttargets for resorts,vacation homes and aquaculture sites. 3. We conducted an inventory of the marshesusing aerial photography and satelliteimages, and evaluatedthe extent and type of developmenton eachmarsh. We reviewedthe availableliterature on the marshesto document their vegetationtypes and ecologicalfunctions in the adjacentmarine and terrestrial ecosystems. 4. Over 95"h of the mangrove marshes have been developed for shrimp farming. However, the larms are built adjacent to, rather than in, the marshes, and the mangrove stands are still mostly intact. -

Indicators for Assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices Part 1 Definitions

Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices PART 1 DEFINITIONS Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices PART 1 DEFINITIONS Conclusions of a consensus meeting held 6–8 November 2007 in Washington, DC, USA WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices : conclusions of a consensus meeting held 6–8 November 2007 in Washington D.C., USA. 1.Infant nutrition. 2.Breast feeding. 3.Bottle feeding. 4.Feeding behavior. 5.Indicators. I.World Health Organization. Dept. of Child and Adolescent Health and Development. ISBN 978 92 4 159666 4 (NLM classification: WS 120) © World Health Organization 2008 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps rep- resent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or rec- ommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

Agronomy of Halophytes As Constructive Use of Saline Systems

Agronomy of Halophytes as Constructive Use of Saline Systems Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Bresdin, Cylphine Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 03:23:03 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/577318 AGRONOMY OF HALOPHYTES AS CONSTRUCTIVE USE OF SALINE SYSTEMS by Cylphine Bresdin A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the department of SOIL, WATER AND ENVIRONMENTAL ScIENCES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WITH A MAJOR IN ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE In the Graduate College ThE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2015 1 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Cylphine Bresdin, titled Agronomy of Halophytes as Constructive Use of Saline Systems and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _____________________________________________________ Date: 7/29/2015 Edward Glenn _____________________________________________________ Date: 7/29/2015 Janick Artiola _____________________________________________________ Date: 7/29/2015 Kevin Fitzsimmons _____________________________________________________ Date: 7/29/2015 Margaret Livingston Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

Minimum Dietary Diversity for Women

MINIMUM DIETARY DIVERSITY FOR WOMEN An updated guide for measurement: from collection to action MINIMUM DIETARY DIVERSITY FOR WOMEN An updated guide for measurement: from collection to action Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 2021 Required citation: FAO. 2021. Minimum dietary diversity for women. Rome. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb3434en The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. ISBN 978-92-5-133993-0 © FAO, 2021 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/legalcode). Under the terms of this licence, this work may be copied, redistributed and adapted for non-commercial purposes, provided that the work is appropriately cited. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that FAO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the FAO logo is not permitted. If the work is adapted, then it must be licensed under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. -

Indicators for Assessing Infant and Young Child Feeding Practices Definitions and Measurement Methods

Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices Definitions and measurement methods Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices Definitions and measurement methods Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: definitions and measurement methods ISBN (WHO) 978-92-4-001838-9 (electronic version) ISBN (WHO) 978-92-4-001839-6 (print version) © World Health Organization and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 2021 This joint report reflects the activities of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO or UNICEF endorses any specific organization, products or services. The unauthorized use of the WHO or UNICEF names or logos is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO) or the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Neither WHO nor UNICEF are responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. -

A Molecular Phylogeny and Classification of the Cynodonteae

TAXON 65 (6) • December 2016: 1263–1287 Peterson & al. • Phylogeny and classification of the Cynodonteae A molecular phylogeny and classification of the Cynodonteae (Poaceae: Chloridoideae) with four new genera: Orthacanthus, Triplasiella, Tripogonella, and Zaqiqah; three new subtribes: Dactylocteniinae, Orininae, and Zaqiqahinae; and a subgeneric classification of Distichlis Paul M. Peterson,1 Konstantin Romaschenko,1,2 & Yolanda Herrera Arrieta3 1 Smithsonian Institution, Department of Botany, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C. 20013-7012, U.S.A. 2 M.G. Kholodny Institute of Botany, National Academy of Sciences, Kiev 01601, Ukraine 3 Instituto Politécnico Nacional, CIIDIR Unidad Durango-COFAA, Durango, C.P. 34220, Mexico Author for correspondence: Paul M. Peterson, [email protected] ORCID PMP, http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9405-5528; KR, http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7248-4193 DOI https://doi.org/10.12705/656.4 Abstract Morphologically, the tribe Cynodonteae is a diverse group of grasses containing about 839 species in 96 genera and 18 subtribes, found primarily in Africa, Asia, Australia, and the Americas. Because the classification of these genera and spe cies has been poorly understood, we conducted a phylogenetic analysis on 213 species (389 samples) in the Cynodonteae using sequence data from seven plastid regions (rps16-trnK spacer, rps16 intron, rpoC2, rpl32-trnL spacer, ndhF, ndhA intron, ccsA) and the nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer regions (ITS 1 & 2) to infer evolutionary relationships and refine the -

The Vascular Flora and Floristic Relationships of the Sierra De La Giganta in Baja California Sur, Mexico Revista Mexicana De Biodiversidad, Vol

Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad ISSN: 1870-3453 [email protected] Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México México León de la Luz, José Luis; Rebman, Jon; Domínguez-León, Miguel; Domínguez-Cadena, Raymundo The vascular flora and floristic relationships of the Sierra de La Giganta in Baja California Sur, Mexico Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, vol. 79, núm. 1, 2008, pp. 29-65 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=42558786034 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 79: 29- 65, 2008 The vascular fl ora and fl oristic relationships of the Sierra de La Giganta in Baja California Sur, Mexico La fl ora vascular y las relaciones fl orísticas de la sierra de La Giganta de Baja California Sur, México José Luis León de la Luz1*, Jon Rebman2, Miguel Domínguez-León1 and Raymundo Domínguez-Cadena1 1Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste S.C. Apartado postal 128, 23000 La Paz, Baja California Sur, Mexico 2San Diego Museum of Natural History. Herbarium. P. O. Box 121390, San Diego, CA 92112 Correspondent: [email protected] Abstract. The Sierra de La Giganta is a semi-arid region in the southern part of the Baja California peninsula of Mexico. Traditionally, this area has been excluded as a sector of the Sonoran Desert and has been more often lumped with the dry-tropical Cape Region of southern Baja California peninsula, but this classical concept of the vegetation has not previously been analyzed using formal documentation. -

Variation in Plant Form in Recurrent Selection Populations of Kansas Rosinseed

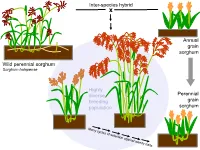

Inter-species hybrid x Annual grain sorghum Wild perennial sorghum Sorghum halapense Highly diverse Perennial breeding grain population sorghum 160 cm BULK06-10 perennial legumes 1. The Land Institute is domesticating Illinois bundleflower (IBF) – Adapted to Great Plains conditions – Nitrogen fixation and seed protein content similar to soybean Dehiscent Indehiscent Pod dropping score (0=marcescent, 2=highly deciduous) 2008 families: 0 0.5 1 2 Indehiscent families 11 13 36 48 Dehiscent families 18 2 2 1 Pod dropping score (0=marcescent, 2=highly deciduous) 2008 families: 0 0.5 1 2 Indehiscent families 11 13 36 48 Dehiscent families 18 2 2 1 2. Existing forage legumes as nitrogen source for perennial cereals Mowed legume intercrop Multi-row mower tractor attachment Late spring: Mow between each row of cereal Early summer: Mowing triggers legume to drop fine roots; nitrogen from decomposing roots and leaves is taken up by the cereal crop 3. Existing perennial grain legumes – but usually grown as annuals • pigeonpea • lab-lab • runner bean • Lima bean Pigeon Pea •Deeply-rooted, perennial •4.92 million hectares worldwide (3.58 million in India alone) •Average yield 898 kg/ha ―The pigeonpea plants, especially of the perennial varieties, have a strong root system, which helps hold the soil on sloping hillsides. ― ―’Pigeonpea has been found to be very successful in covering the soil and reducing soil erosion," says Dr Zong Xuxiao, from the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences at Beijing.’‖ http://www.cgiar.org/newsroom/releases/news.asp?idnews=536 -

Flora of Southwestern Arizona

Felger, R.S., S. Rutman, and J. Malusa. 2014. Ajo Peak to Tinajas Altas: A flora of southwestern Arizona. Part 6. Poaceae – grass family. Phytoneuron 2014-35: 1–139. Published 17 March 2014. ISSN 2153 733X AJO PEAK TO TINAJAS ALTAS: A FLORA OF SOUTHWESTERN ARIZONA Part 6. POACEAE – GRASS FAMILY RICHARD STEPHEN FELGER Herbarium, University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona 85721 & Sky Island Alliance P.O. Box 41165, Tucson, Arizona 85717 *Author for correspondence: [email protected] SUSAN RUTMAN 90 West 10th Street Ajo, Arizona 85321 JIM MALUSA School of Natural Resources and the Environment University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona 85721 [email protected] ABSTRACT A floristic account is provided for the grass family as part of the vascular plant flora of the contiguous protected areas of Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, and the Tinajas Altas Region in southwestern Arizona. This is the second largest family in the flora area after Asteraceae. A total of 97 taxa in 46 genera of grasses are included in this publication, which includes ones established and reproducing in the modern flora (86 taxa in 43 genera), some occurring at the margins of the flora area or no long known from the area, and ice age fossils. At least 28 taxa are known by fossils recovered from packrat middens, five of which have not been found in the modern flora: little barley ( Hordeum pusillum ), cliff muhly ( Muhlenbergia polycaulis ), Paspalum sp., mutton bluegrass ( Poa fendleriana ), and bulb panic grass ( Zuloagaea bulbosa ). Non-native grasses are represented by 27 species, or 28% of the modern grass flora. -

Revisión Del Aceite De Orégano Spp. En Salud Y Producción Animal Review of the Use of Oregano Oil Spp

ABANICO AGROFORESTAL ISSN 2594-1992 abanicoacademico.mx/revistasabanico/index.php/abanico-agroforestal Abanico Agroforestal. Enero-Diciembre 2020; 2:1-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.37114/abaagrof/2020.1 Artículo Revisión. Recibido: 16/06/2019. Aceptado: 15/11/2019. Publicado: 01/04/2020. Revisión del aceite de orégano spp. en salud y producción animal Review of the use of oregano oil spp. in animal health and production Loeza-Concha Henry1** , Salgado-Moreno Socorro2 , Ávila-Ramos Fidel3 , Gutiérrez-Leyva Ranferi2 , Domínguez-Rebolledo Alvaro4 , Ayala-Martínez Maricela5 , Escalera-Valente Francisco2* 1Colegio de Posgraduados, Campus Campeche, Sihochac, Champotón, Campeche, México. 2Unidad Académica de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia, Universidad Autónoma de Nayarit, Nayarit, México. 3División de Ciencias de la Vida, Universidad de Guanajuato Irapuato, Guanajuato, México. 4Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias-Mocochá, Mérida, México. 5Instituto de Ciencias Agropecuarias, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo. México. *Autor de correspondencia: Francisco Escalera Valente. **Autor responsable: Henry Loeza-Concha. [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. RESUMEN El uso de los aceites esenciales extraído del orégano son relevantes si tomamos en cuenta sus cantidades de timol, flavonoides, taninos, triterpenos y carvacrol contenido, las cuales le dan su capacidad antioxidante, para disminuir