Benjamin Graham on Fixed Income

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Synergies of Hedge Funds and Reinsurance

The Synergies of Hedge Funds and Reinsurance Eric Andersen May 13th, 2013 Advisor: Dwight Jaffee Department of Economics University of California, Berkeley Acknowledgements I would like to convey my sincerest gratitude to Dr. Dwight Jaffee, my advisor, whose support and assistance were crucial to this project’s development and execution. I also want to thank Angus Hildreth for providing critical feedback and insightful input on my statistical methods and analyses. Credit goes to my Deutsche Bank colleagues for introducing me to and stoking my curiosity in a truly fascinating, but infrequently studied, field. Lastly, I am thankful to the UC Berkeley Department of Economics for providing me the opportunity to engage this project. i Abstract Bermuda-based alternative asset focused reinsurance has grown in popularity over the last decade as a joint venture for hedge funds and insurers to pursue superior returns coupled with insignificant increases in systematic risk. Seeking to provide permanent capital to hedge funds and superlative investment returns to insurers, alternative asset focused reinsurers claim to outpace traditional reinsurers by providing exceptional yields with little to no correlation risk. Data examining stock price and asset returns of 33 reinsurers from 2000 through 2012 lends little credence to support such claims. Rather, analyses show that, despite a positive relationship between firms’ gross returns and alternative asset management domiciled in Bermuda, exposure to alternative investments not only fails to mitigate market risk, but also may actually eliminate any exceptional returns asset managers would have otherwise produced by maintaining a traditional investment strategy. ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................... i Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... -

29:390:470:01 & 02 COURSE TITLE: Security Analysis

Department of Finance and Economics COURSE NUMBER: 29:390:470:01 & 02 COURSE TITLE: Security Analysis COURSE MATERIALS Lecture notes and assignments will be distributed via Blackboard. Required Textbooks: 1) “Value Investing – from Graham to Buffett and Beyond”, Bruce Greenwald, Judd Kahn, Paul Sonkin and Michael Biema. Wiley Finance. ISBN 0-471-46339-6 2) “The Warren Buffett Way”, 3rd Edition, Robert Hagstrom, Wiley Other readings (buy used copies): 3) “The Intelligent Investor”, Benjamin Graham. Revised Edition 2006 by Harper Collins Publishers. ISBN-10 0-06-055566-1 4) “Security Analysis”, 1951 Edition”, Benjamin Graham & David L. Dodd by McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-07-144820-9 5) “The Essays of Warren Buffett: Lessons for Corporate America”, First Revised Edition, by Lawrence A. Cunningham, ISBN-10: 0-9664461-1-9 6) “Investment Banking: Valuation, Leveraged Buyouts, and Mergers and Acquisitions”, Joshua Rosenbaum, Joshua Pearl and Joseph R. Perella (Wiley Finance) 2009. ISBN 978-0-470-44220-3 FINAL GRADE ASSIGMENT Grades Mid-Term: 40% Equity Challenge competition: 60% (team work) Teams: Each student must be part of a team of 4 members. Please take advantage of student diversity in your class. Your team is expected to work on class assignments and the equity challenge competition. 1 Department of Finance and Economics (29:390:470) COURSE SCHEDULE Course Outline Week 1: Principles of Security Analysis Lectures 1A & 1B Buying a business Lecture 1C Read Accounting Clinic 1 Appendix 1 Week 2: Balance Sheet, Income Statement Lectures 2A & 2B Appendix -

The Mecca of Value Investing

The mecca of Value Investing Subject: The mecca of Value Invesng From: CSH Investments <[email protected]> Date: 6/18/2019, 1:44 PM To: Randy <[email protected]> View this email in your browser Some of you know I'm a big believer in lifetime learning. It wasn't always the case. My early academic years were less than stellar. But I caught on fairly quickly and made do. By my late 20's I knew I wanted to be in finance. I had studied finance and economics in college but it didn't really grab me. Looking back partly it was me but also it was the way it was taught. Stodgy old theories that really didn't make any sense to me. The Efficient Market Theory for instance. EMT says basically that the markets are fully efficient. That stocks are perfectly priced therefore there aren't any bargains. You have absolutely nothing to gain from fundamental analysis and if you do it you are wasting your time. Yeah I thought but I knew there were guys who did exactly that. They did 1 of 5 6/18/2019, 4:48 PM The mecca of Value Investing their own research and found things that were mispriced. Most of them were quite wealthy. If the market is perfectly efficient as you say then how can they do it? And almost every theory had a list of assumptions you had to make. Here's one I love, every investor has the same information. Well, let's just be logical every investor doesn't have the same information and even if they did they would interpret differently. -

The Intelligent Investor

THE INTELLIGENT INVESTOR A BOOK OF PRACTICAL COUNSEL REVISED EDITION BENJAMIN GRAHAM Updated with New Commentary by Jason Zweig An e-book excerpt from To E.M.G. Through chances various, through all vicissitudes, we make our way.... Aeneid Contents Epigraph iii Preface to the Fourth Edition, by Warren E. Buffett viii ANote About Benjamin Graham, by Jason Zweigx Introduction: What This Book Expects to Accomplish 1 COMMENTARY ON THE INTRODUCTION 12 1. Investment versus Speculation: Results to Be Expected by the Intelligent Investor 18 COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 1 35 2. The Investor and Inflation 47 COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 2 58 3. A Century of Stock-Market History: The Level of Stock Prices in Early 1972 65 COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 3 80 4. General Portfolio Policy: The Defensive Investor 88 COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 4 101 5. The Defensive Investor and Common Stocks 112 COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 5 124 6. Portfolio Policy for the Enterprising Investor: Negative Approach 133 COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 6 145 7. Portfolio Policy for the Enterprising Investor: The Positive Side 155 COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 7 179 8. The Investor and Market Fluctuations 188 iv v Contents COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 8 213 9. Investing in Investment Funds 226 COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 9 242 10. The Investor and His Advisers 257 COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 10 272 11. Security Analysis for the Lay Investor: General Approach 280 COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 11 302 12. Things to Consider About Per-Share Earnings 310 COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 12 322 13. A Comparison of Four Listed Companies 330 COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 13 339 14. -

Benjamin Graham: the Father of Financial Analysis

BENJAMIN GRAHAM THE FATHER OF FINANCIAL ANALYSIS Irving Kahn, C.F.A. and Robert D. M£lne, G.F.A. Occasional Paper Number 5 THE FINANCIAL ANALYSTS RESEARCH FOUNDATION Copyright © 1977 by The Financial Analysts Research Foundation Charlottesville, Virginia 10-digit ISBN: 1-934667-05-6 13-digit ISBN: 978-1-934667-05-7 CONTENTS Dedication • VIlI About the Authors • IX 1. Biographical Sketch of Benjamin Graham, Financial Analyst 1 II. Some Reflections on Ben Graham's Personality 31 III. An Hour with Mr. Graham, March 1976 33 IV. Benjamin Graham as a Portfolio Manager 42 V. Quotations from Benjamin Graham 47 VI. Selected Bibliography 49 ******* The authors wish to thank The Institute of Chartered Financial Analysts staff, including Mary Davis Shelton and Ralph F. MacDonald, III, in preparing this manuscript for publication. v THE FINANCIAL ANALYSTS RESEARCH FOUNDATION AND ITS PUBLICATIONS 1. The Financial Analysts Research Foundation is an autonomous charitable foundation, as defined by Section 501 (c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. The Foundation seeks to improve the professional performance of financial analysts by fostering education, by stimulating the development of financial analysis through high quality research, and by facilitating the dissemination of such research to users and to the public. More specifically, the purposes and obligations of the Foundation are to commission basic studies (1) with respect to investment securities analysis, investment management, financial analysis, securities markets and closely related areas that are not presently or adequately covered by the available literature, (2) that are directed toward the practical needs of the financial analyst and the portfolio manager, and (3) that are of some enduring value. -

The Association of Exchange Rates and Stock Returns. (Linear Regression Analysis)

March 2007 U.S.B.E- Umeå School of Business Masters Program: Accounting and Finance Masters Thesis- Spring Semester 2007 Author : Akumbu Martin Nshom Supervisor : Stefan Sundgren Thesis seminar : 7 th May 2007 The Association of Exchange rates and Stock returns. (Linear regression Analysis) Acknowledgement I will start by thanking God Almighty for giving me the intellect to complete this project. A big thanks goes to my supervisor Stefan Sundgren for giving me guidance and all the help I needed to complete this thesis To my family for their continuous help and support to see that I under take my studies here especially my Mother Lydia Botame. Finally to all my friends and well wishers who supported me in one way or an other through out my stay here in Umeå, may God bless you all! ABSTRACT The association of exchange rates with stock returns and performance in major trading markets is widely accepted. The world’s economy has seen unprecedented growth of interdependent; as such the magnitude of the effect of exchange rates on returns will be even stronger. Since the author perceives the importance of exchange rates on stock returns, the author found it interesting to study the effect of exchange rates on some stocks traded on the Stock exchange. There has been a renewed interest to investigate the relationship between returns and exchange rates as such; the author has chosen to investigate the present study to focus in the United Kingdom with data from the London Stock exchange .The author carried out his research on 18 companies traded on the London Stock Exchange in the process, using linear regression analysis. -

The Intelligent Investor: the Definitive Book on Value Investing. a Book of Practical Counsel by Benjamin Graham and Jason Zweig

The Intelligent Investor: The Definitive Book on Value Investing. A Book of Practical Counsel by Benjamin Graham and Jason Zweig Security Analysis: Sixth Edition, Foreword by Warren Buffett by Benjamin Graham and David Dodd Contrarian Investment Strategies: The Psychological Edge by David Dreman Margin of Safety: Risk-Averse Value Investing Strategies for the Thoughtful Investor by Seth A. Klarman What Has Worked In Investing: Studies of Investment Approaches and Characteristics Associated with Exceptional Returns by Tweedy, Browne Company LLC Value Investing: From Graham to Buffett and Beyond by Bruce C. N. Greenwald and Judd Kahn The Little Book That Builds Wealth: The Knockout Formula for Finding Great Investments by Pat Dorsey The Five Rules for Successful Stock Investing: Morningstar's Guide to Building Wealth and Winning in the Market by Pat Dorsey Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits and Other Writings by Philip A. Fisher The Investment Checklist: The Art of In-Depth Research by Michael Shearn Financial Statements: A Step-by-Step Guide to Understanding and Creating Financial Reports by Thomas R. Ittelson Active Value Investing: Making Money in Range-Bound Markets by Vitaliy N. Katsenelson The Little Book of Sideways Markets: How to Make Money in Markets that Go Nowhere by Vitaliy N. Katsenelson The Art of Value Investing: How the World's Best Investors Beat the Market by John Heins and Whitney Tilson The Art of Short Selling Hardcover by Kathryn F. Staley The Most Important Thing Illuminated: Uncommon Sense for the Thoughtful Investor by Howard Marks and Paul Johnson Financial Shenanigans: How to Detect Accounting Gimmicks & Fraud in Financial Reports, 3rd Edition by Howard Schilit and Jeremy Perler Quality of Earnings by Thornton L. -

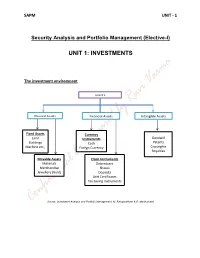

Unit 1: Investments

SAPM UNIT - 1 Security Analysis and Portfolio Management (Elective-I) UNIT 1: INVESTMENTS The investment environment ASSETS Physical Assets Financial Assets Intangible Assets Fixed Assets Currency Goodwill Land Instruments Patents Buildings Cash Machine etc., Copyrights Foregn Currency Royalties Movable Assets Claim Instruments Materials Debentures Merchandise Shares Jewellery (Gold) Deposits Unit Certificates Tax Saving Instruments Source: Investment Analysis and Portfolio Management, M. Ranganatham & R. Madhumathi SAPM UNIT - 1 Classification of Financial Markets: Financial Markets Securities Market Currency Market/ Forex market National Market International Market Domestic Segment Foreign Segment Capital Market Money Market Equity Market Debt Market Primary Market Secondary Market Spot Market Derivative Market Source: Investment Analysis and Portfolio Management, M. Ranganatham & R. Madhumathi SAPM UNIT - 1 SAPM UNIT - 1 Investment Meaning & Definition: investment is an activity that is engaged in by people who have savings i.e. investments are made from savings. Investment may be defined as a “commitment of funds made in the expectations of some positive rate of return.” Characteristics of Investment: Return Risk Safety Liquidity Objectives of Investment: Maximisation of Return Minimization of Risk Hedge against Inflation Investment Vs Speculation: Traditionally investment is distinguished from speculation with respect to four factors. These are: Risk Capital Gain Time Period Leverage Financial instruments (Investment Avenues available in India): Corporate Securities Deposits in banks and non-banking companies UTI and other mutual fund schemes SAPM UNIT - 1 Post office deposits and certificates Life insurance policies Provident fund schemes Government and semi government securities Regulatory Environment: In India the ministry of finance, the reserve bank of india, the securities and exchange board of India etc. -

Ba7021 Security Analysis and Portfolio Management 1 Sce

BA7021 SECURITY ANALYSIS AND PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT A Course Material on SECURITY ANALYSIS AND PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT By Mrs.V.THANGAMANI ASSISTANT PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF MANAGEMENT SCIENCES SASURIE COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING VIJAYAMANGALAM 638 056 1 SCE DEPARTMENT OF MANAGEMENT SCIENCES BA7021 SECURITY ANALYSIS AND PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT QUALITY CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the e-course material Subject Code : BA7021 Subject : Security Analysis and Portfolio Management Class : II Year MBA Being prepared by me and it meets the knowledge requirement of the university curriculum. Signature of the Author Name : V.THANGAMANI Designation: Assistant Professor This is to certify that the course material being prepared by Mrs.V.THANGAMANI is of adequate quality. He has referred more than five books amount them minimum one is from abroad author. Signature of HD Name: S.Arun Kumar SEAL 2 SCE DEPARTMENT OF MANAGEMENT SCIENCES BA7021 SECURITY ANALYSIS AND PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT CONTENTS CHAPTER TOPICS PAGE NO INVESTMENT SETTING 1.1 Financial meaning of investment 1.2 Economic meaning of Investment 7-25 1 1.3 Characteristics and objectives of Investment 1.4 Types of Investment 1.5 Investment alternatives 1.6 Choice and Evaluation 1.7 Risk and return concepts. SECURITIES MARKETS 2.1 Financial Market 2.2 Types of financial markets 2.3 Participants in financial Market 2.4 Regulatory Environment 2 2.5 Methods of floating new issues, 26-64 2.6 Book building 2.7 Role & Regulation of primary market 2.8 Stock exchanges in India BSE, OTCEI , NSE, ISE 2.9 Regulations of stock exchanges 2.10 Trading system in stock exchanges 2.11 SEBI FUNDAMENTAL ANALYSIS 3.1 Fundamental Analysis 3.2 Economic Analysis 3.3 Economic forecasting 3.4 stock Investment Decisions 3.5 Forecasting Techniques 3 3.6 Industry Analysis 65-81 3.7 Industry classification 3.8 Industry life cycle 3.9 Company Analysis 3.10Measuring Earnings 3.11 Forecasting Earnings 3.12 Applied Valuation Techniques 3.13 Graham and Dodds investor ratios. -

Security Analysis and Portfolio Management

TECEP® Test Description for FIN-321-TE SECURITY ANALYSIS AND PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT Security Analysis and Portfolio Management presents an overview of investments with a focus on asset types, financial instruments, security markets, and mutual funds. The course provides a foundation for students entering the fields of investment analysis or portfolio management. This course examines portfolio theory, debt and equity securities, and derivative markets. It provides information on sound investment management practices, emphasizing the impact of globalization, taxes, and inflation on investments. It also provides guidance in evaluating the performance of an investment portfolio. (3 credits) ● Test format: 80 multiple choice questions (1 point each). ● Passing score: 60% (48/80 points). Your grade will be reported as CR (credit) or NC (no credit). ● Time limit: 2 hours Note: Scientific, graphing or financial calculator allowed (no phones or tablets); one sheet of scratch paper at a time, can request additional sheets. OUTCOMES ASSESSED ON THE TEST ● Discuss financial assets, financial markets, and the role of financial intermediaries ● Differentiate among equity and debt markets and stock and bond market indexes ● Assess the mechanics of various securities markets, mutual funds/investment companies, and the roles of investment bankers and brokers ● Calculate the expected rate of return from risky and risk-free investment portfolios ● Analyze portfolio theory, including measures of risk ● Discuss bond characteristics and compute bond prices and yields ● Explain equity valuation models ● Evaluate the effects of equity expense calculations, including EPS, P/E, dividends, stock betas ● Describe options and futures markets TECEP Test Description for FIN-321-TE by Thomas Edison State University is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. -

The Intelligent Investor: 100 Page Summary Ebook, Epub

THE INTELLIGENT INVESTOR: 100 PAGE SUMMARY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Preston Pysh,Stig Brodersen | 108 pages | 19 Feb 2014 | 100 Page Summaries | 9781939370112 | English | United States The Intelligent Investor: 100 Page Summary PDF Book The truth is some will not live up to expectations. The outcome is definitely not desirable. To reach long-term success, every active investor has to evaluate each investment very carefully and above all diversify its portfolio among the most profitable industries. However, armed with this knowledge concerning the fallibility of mutual funds, the intelligent investor is better equipped to discern a more solid mutual fund from a more volatile one. However, some defensive investors do enjoy the intellectual challenge of picking some individual stocks. Fair to assume that outstandingly successful company has unusually good management. He said that if we pay special attention to those 2 chapters, we will not get a poor result from our investments. Go to Top. His principles of investing safely and successfully continue to influence investors today. He ended up being the professor for Warren Buffett. And I also wanted something that had that compared a stock to stock but it was also taking into account the risk appetite. Graham suggests 20 years. Always have a margin of safety. That way, you have to rely on your intuition. Ultimately, Graham states that the only thing an investor can be sure about when attempting to forecast future stock returns, is that they will probably turn out to be wrong. Or how much they should be saving to meet their financial goals. One is giving you double the return of the other, but you have a lot more risk associated with one versus the other. -

Security Analysis: an Investment Perspective

Security Analysis: An Investment Perspective Kewei Hou∗ Haitao Mo† Chen Xue‡ Lu Zhang§ Ohio State and CAFR LSU U. of Cincinnati Ohio State and NBER March 2020¶ Abstract The investment CAPM, in which expected returns vary cross-sectionally with invest- ment, profitability, and expected growth, is a good start to understanding Graham and Dodd’s (1934) Security Analysis within efficient markets. Empirically, the q5 model goes a long way toward explaining prominent equity strategies rooted in security anal- ysis, including Frankel and Lee’s (1998) intrinsic-to-market value, Piotroski’s (2000) fundamental score, Greenblatt’s (2005) “magic formula,” Asness, Frazzini, and Peder- sen’s (2019) quality-minus-junk, Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway, Bartram and Grinblatt’s (2018) agnostic analysis, and Penman and Zhu’s (2014, 2018) expected return strategies. ∗Fisher College of Business, The Ohio State University, 820 Fisher Hall, 2100 Neil Avenue, Columbus OH 43210; and China Academy of Financial Research (CAFR). Tel: (614) 292-0552. E-mail: [email protected]. †E. J. Ourso College of Business, Louisiana State University, 2931 Business Education Complex, Baton Rouge, LA 70803. Tel: (225) 578-0648. E-mail: [email protected]. ‡Lindner College of Business, University of Cincinnati, 405 Lindner Hall, Cincinnati, OH 45221. Tel: (513) 556-7078. E-mail: [email protected]. §Fisher College of Business, The Ohio State University, 760A Fisher Hall, 2100 Neil Avenue, Columbus OH 43210; and NBER. Tel: (614) 292-8644. E-mail: zhanglu@fisher.osu.edu. ¶For helpful comments,