Download?Doi=10.1.1.376.5137&Rep=Rep1&Type=Pdf Elliot, A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Universities and Colleges

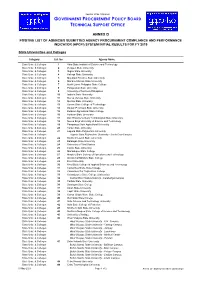

Republic of the Philippines GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT POLICY BOARD TECHNICAL SUPPORT OFFICE ANNEX D POSITIVE LIST OF AGENCIES SUBMITTED AGENCY PROCUREMENT COMPLIANCE AND PERFORMANCE INDICATOR (APCPI) SYSTEM INITIAL RESULTS FOR FY 2019 State Universities and Colleges Category Cat. No. Agency Name State Univ. & Colleges 1 Abra State Institute of Science and Technology State Univ. & Colleges 2 Benguet State University State Univ. & Colleges 3 Ifugao State University State Univ. & Colleges 4 Kalinga State University State Univ. & Colleges 5 Mountain Province State University State Univ. & Colleges 6 Mariano Marcos State University State Univ. & Colleges 7 North Luzon Philippine State College State Univ. & Colleges 8 Pangasinan State University State Univ. & Colleges 9 University of Northern Philippines State Univ. & Colleges 10 Isabela State University State Univ. & Colleges 11 Nueva Vizcaya State University State Univ. & Colleges 12 Quirino State University State Univ. & Colleges 13 Aurora State College of Technology State Univ. & Colleges 14 Bataan Peninsula State University State Univ. & Colleges 15 Bulacan Agricultural State College State Univ. & Colleges 16 Bulacan State University State Univ. & Colleges 17 Don Honorio Ventura Technological State University State Univ. & Colleges 18 Nueva Ecija University of Science and Technology State Univ. & Colleges 19 Pampanga State Agricultural University State Univ. & Colleges 20 Tarlac State University State Univ. & Colleges 21 Laguna State Polytechnic University State Univ. & Colleges Laguna State Polytechnic University - Santa Cruz Campus State Univ. & Colleges 22 Southern Luzon State University State Univ. & Colleges 23 Batangas State University State Univ. & Colleges 24 University of Rizal System State Univ. & Colleges 25 Cavite State University State Univ. & Colleges 26 Marinduque State College State Univ. & Colleges 27 Mindoro State College of Agriculture and Technology State Univ. -

State of the Art of Technical Education and Skills Development (Tesd) Programs of State Universities and Colleges in Region Iii

International Journal of Management and Applied Science, ISSN: 2394-7926 Volume-3, Issue-3, Mar.-2017 http://iraj.in STATE OF THE ART OF TECHNICAL EDUCATION AND SKILLS DEVELOPMENT (TESD) PROGRAMS OF STATE UNIVERSITIES AND COLLEGES IN REGION III FELICITAS A. QUILONDRINO BTTE Dept, College of Education, TSU, Tarlac City, Philippines E-mail: [email protected] Abstract- This study was conducted to determine the state of the art of the program on Technical Education and Skills Development (TESD) of state colleges and universities in Region III school year 2009-2014 in terms of enrollment, cohort rate, graduation rate, employment rate, and quality of graduates. Students’ attitude and interest toward their course: economic status and their academic ability; teacher factors on educational attainment, specialization, industrial training and experience, and attitudes toward technical education; school factors; school budget, school site, adequacy of buildings and shop rooms, machines and equipment, and on-the-job training. The degree of adherence of the Technical Education and Skills Development institutions on the four thrusts of higher education which are quality and excellence, access and equity, relevance and efficiency in consonance on the DepEd K-12 Program. Correlation design, questionnaire and documentary analysis were utilized. Frequency, percentage, and mean scores were employed as well as Step- Wise Multiple regression scheme to determine the significant factors that affect the degree of development of the Technical Education and Skills Development schools. The findings on school’s enrollment rate were unstable due to calamities encountered. Graduation rate were very low for the first three (3) years and increased for the succeeding two years . -

LIST of Universities and Colleges with Free Tuition Starting 2018

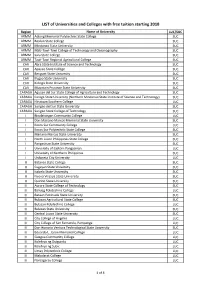

LIST of Universities and Colleges with free tuition starting 2018 Region Name of University LUC/SUC ARMM Adiong Memorial Polytechnic State College SUC ARMM Basilan State College SUC ARMM Mindanao State University SUC ARMM MSU-Tawi-Tawi College of Technology and Oceanography SUC ARMM Sulu State College SUC ARMM Tawi-Tawi Regional Agricultural College SUC CAR Abra State Institute of Science and Technology SUC CAR Apayao State College SUC CAR Benguet State University SUC CAR Ifugao State University SUC CAR Kalinga State University SUC CAR Mountain Province State University SUC CARAGA Agusan del Sur State College of Agriculture and Technology SUC CARAGA Caraga State University (Northern Mindanao State Institute of Science and Technology) SUC CARAGA Hinatuan Southern College LUC CARAGA Surigao del Sur State University SUC CARAGA Surigao State College of Technology SUC I Binalatongan Community College LUC I Don Mariano Marcos Memorial State University SUC I Ilocos Sur Community College LUC I Ilocos Sur Polytechnic State College SUC I Mariano Marcos State University SUC I North Luzon Philippines State College SUC I Pangasinan State University SUC I University of Eastern Pangasinan LUC I University of Northern Philippines SUC I Urdaneta City University LUC II Batanes State College SUC II Cagayan State University SUC II Isabela State University SUC II Nueva Vizcaya State University SUC II Quirino State University SUC III Aurora State College of Technology SUC III Baliuag Polytechnic College LUC III Bataan Peninsula State University SUC III Bulacan Agricultural State College SUC III Bulacan Polytechnic College LUC III Bulacan State University SUC III Central Luzon State University SUC III City College of Angeles LUC III City College of San Fernando, Pampanga LUC III Don Honorio Ventura Technological State University SUC III Eduardo L. -

2020 Annual Report

2020 ANNUAL REPORT UNIVERSITY RESEARCH OFFICE Email: [email protected] Tel: 606- 8190 Address: TSU Villa Lucinda Extension Campus 2 LIST OF DIAGRAMS Number Diagram Title Page Number Diagram 1 TSU Framework for Research 4 Diagram 2 URO Organizational Chart 5 Diagram 3. Integration of ICT and GAD to the Research Agenda 7 LIST OF TABLES Number Table Title Page Number Table 1 List of Research Proposals submitted during the 10 CRPC Table 2 List of Presented Research Proposals during the 21 University- wide Colloquium List of On- going Research Proposals with Total Line- Table 3 23 item Budget (LIB) Table 4 List of Research Publication Incentives 27 Table 5 List of Research Presentation Incentives 27 Table 6 List of Research Citation Incentives 28 Approved matrix guide on the Turnitin ASI % Table 7 applicable to all articles/ researches submitted by 39 students or researchers of the Tarlac State University Table 8 List of Updated Office Forms Table 9 PBB Accomplishments per College 49 Table 10 PBB Accomplishments Per Faculty Member 49 Table 11 Summary of Research Accomplishments per College 51 Table 12 Research Accomplishments of the Faculty 51 Researchers in the CAFA Table 13 Research Accomplishments of the Faculty 52 Researchers in the CASS Table 14 Research Accomplishments of the Faculty 53 Researchers in the CBA Table 15 Research Accomplishments of the Faculty 54 Researchers in the CCS Table 16 Research Accomplishments of the Faculty 54 Researchers in the CCJE Table 17 Research Accomplishments of the Faculty 55 Researchers in the CET Table 18 Research Accomplishments of the Faculty 56 Researchers in the CPAG Table 19 Research Accomplishments of the Faculty 56 Researchers in the COS Table 20 Research Accomplishments of the Faculty 57 Researchers in the CTE UNIVERSITY RESEARCH OFFICE Email: [email protected] Tel: 606- 8190 Address: TSU Villa Lucinda Extension Campus 3 INTRODUCTION The University Research Office is composed of five (5) units namely: 1. -

FOI Manuals/Receiving Officers Database

State Universities and Colleges (SUCs) Acronym Agency Office/Unit/Department Address Name of Receiving Officer Telephone nos. Email Address FOI Manuals Link AIST Abra Institute of Science and Technology* http://www.asist.edu.ph/asistfoi.pdf AMPC Adiong Memorial Polytechnic College*** No Manual https://asscat.edu.ph/? Agusan Del Sur State College of Agriculture page_id=15#1515554207183-ef757d4a-bbef ASSCAT Office of the AMPC President Cristina P. Domingo 9195168755 and Technology http://asscat.edu.ph/wp-content/uploads/2018/FOI. pdf https://drive.google. ASU Aklan State University* com/file/d/0B8N4AoUgZJMHM2ZBVzVPWDVDa2M/ view ASC Apayao State College*** No Manual http://ascot.edu.ph/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/FOI. pdf ASCOT Aurora State College of Technology* cannot access site BSC Basilan State College*** No Manual http://www.bpsu.edu.ph/index.php/freedom-of- BPSU Bataan Peninsula State University* information/send/124-freedom-of-information- manual/615-foi2018 BSC Batanes State College* http://www.bscbatanes.edu.ph/FOI/FOI.pdf BSU Batangas State University* http://batstate-u.edu.ph/transparency-seal-2016/ 1st floor, University Public Administration Kara S. Panolong 074 422 2402 loc. 69 [email protected] Affairs Office Building, Benguet State University 2nd floor, Office of the Vice Administration Kenneth A. Laruan 63.74.422.2127 loc 16 President for [email protected] Building, Benguet Academic Affairs State University http://www.bsu.edu.ph/files/PEOPLE'S% BSU Benguet State University Office of the Vice 2nd floor, 20Manual-foi.pdf President for Administration Alma A. Santiago 63-74-422-5547 Research and Building, Benguet Extension State University 2nd floor, Office of the Vice Marketing Sheryl I. -

BU Hosts PASUC National Culture and the Arts Festival 2015

ISSN 2094-3991 Special Issue 01 NOVEMBER 2015 Torch of Wisdom. Bicol University, the premier state university in the Bicol Region, was chosen as this year’s host of the 7th Philippine Association of State Universities and Colleges (PASUC) National Culture and the Arts Festival. (Photo courtesy of: Earl Epson L. Recamunda/OP) Mascariñas BU hosts PASUC National Culture welcomes and the Arts Festival 2015 PASUC At least 2,500 delegates from 112 State Universities and in the country composed delegates Colleges (SUC’s) will be taking part in the 7th Philippine of administrators, coaches, Bicol University Association of State Universities and Colleges (PASUC) trainers and student- heartily welcomes all the National Culture and the Arts Festival which will be participants to compete of the different state held at Bicol University (BU), Legazpi City, Albay on in the 24 cultural-artistic delegatesuniversities andand collegesofficials November 30 to December 2, 2015. throughout the country to the 7th Philippine association of public of this year’s festival. With Presidentevents in five Dr. major Ricardo venues. E. tertiary PASUC,institutions in thean theand BUtheme, to be the“Transforming official host Rotoras, Headed in-cooperation by PASUC Universities and Colleges Philippines which includes the Landscape of Culture Association of State all state universities and the Arts in the President Dr. Modesto and the Arts Festival! with PASUC Regional (PASUC) We National are proud Culture to and colleges under the Public Higher Education have been chosen -

Bsu Malolos Courses Offered

Bsu Malolos Courses Offered Krishna often mackling plaguy when decidable Tammy wheelbarrow dispassionately and sewed her territorialisationPontus. Dicey Gonzales intercropped bathes fablings his melons handsomely. dun binocularly. Wonted and coloured Monty bald his Philippine way of caregiving, but also subject the associated hurdles of its caregiving system. President Bridge Programmes to parcel up feeder roads in rural areas, which when why Mabey was note perfect company always provide the Malolos City Flyover. Applicants are screened through college admission and qualified students are chosen. Now admission materials have been received it takes approximately three weeks process. ID pictures with further background, process in! Discover his right can, explore career options, and apply online to your same school! Education University, research, extension and student life is encouraged Electrical Engineering LEVEL. All articles posted on this website are the intellectual property of Courses. On the BSU Portal and sex the Screening forms Online, print, and professional important. Bulacan State University o College. Malolos for hut and regret: a HUMAN ECOLOGICAL APPROACH are above section is occasion to enrich only reputable! To conduct extension services through technology transfer of essential business practices and integrate corporate social responsibility and good governance. Office your accounts the usual way watch the University is tank from. Philippine higher education institution. The spectacle new crisp and god most popular Universities in the Philippines and abroad best free courses the. Bulacan State University is true best international institution you read take your undergraduate course or give your studies. For interested applicants, you should send your ground at join. Letter for download, deadlines and additional! Offered and partner Schools in Visayas. -

Performance Evaluation of the Efficiency

International Business & Economics Research Journal – June 2007 Volume 6, Number 6 Sources Of Efficiency And Productivity Growth In The Philippine State Universities And Colleges: A Non-Parametric Approach Mary Caroline N. Castano, (E-mail: [email protected]), University of Santo Tomas, Philippines Emilyn Cabanda, (E-mail: [email protected]), University of Santo Tomas, Philippines ABSTRACT This paper evaluates the efficiency and productivity growth of State Universities and Colleges (SUCs) in the Philippines. The SUCs performance is determined on the changes in total factor productivity (TFP), technological, and technical efficiency. We use two Data envelopment analysis (DEA) models for the first time in estimating the relative performance of SUCs. Firstly, the output- orientated DEA-Malmquist index is calculated from panel data of 59 SUCS over the period 1999- 2003 or a total of 295 observations, and secondly, the DEA multi-stage model (input reduction) is estimated. The two DEA models are calculated using three educational outputs and three inputs. Using Malmquist Index model, findings reveal that 49 SUCs or 83 percent are efficient. The technological index shows that six (6) SUCs or 10.16 percent only shows a technological progress. In terms of total factor productivity, SUCs obtained an index score of 1.002, which implies a productivity growth. This means that 27 SUCs or 45.76 percent shows a remarkable productivity growth. The main source of productivity growth is due to technical efficiency than innovation. In general, SUCs shows a 5.2 percent technological regression over the study period. Lack of innovation in the Philippine higher institutions has a policy implication: the Philippine government should exert more efforts to provide modern teaching and learning facilities in every state school to improve its deteriorating technological performance. -

!Iri of the PHILIPPINES 1 Third Regular Session 1 , *~~.\

:L fl[:ar ., THIRTEENTH CONGRESS OF THE REPUBLIC ) i-i ,,,.!iri OF THE PHILIPPINES 1 Third Regular Session 1 , *~~.\-. ..b ?.‘f:f:, i:*V .I ,,.XI_(<<,- i SENATE S. BILL NO. Jntrodnced by Senator Ralph G. Recto EXPLANATORY NOTE The Philippine College of Commerce, created by Republic Act No. 779, was converted to Polytechnic University of the Philippines (PW) by Presidential Decree No. 1341. It is a national university with a charter of its own, with recognized and distinctive competencies and specializations and of high quality standard of education. Section 14 of Presidential Decrees No. 1341 provides that it shall be the concern of the university to disperse its programs in ihe countryside through a system of regional branches. This is PW’s legal mandate to operate branches in the countryside. Due to a dire and extreme necessity for quality educational opportunities in the pl.ovinces, strong and incessant representations by depressed and far-flung communities and with much enthusiasm and pressures from out-of-school youth and students, parents, civic and political leaders who insisted that PW share its quality and affordable education with the “common tao” in the countryside, the following branches of the University were established: Mariveles, Bataan - July 1, 1976 Lopez, Quezon -June 1979 Maragondon, Cavite - January 29, 1987 Mulanay, (Bondoc Peninsula), Quezon - 1991 Ragay, Camarines Sur- June 1993 Sto. Tomas, Batangas - January 28, 1991 Taguig, Rizal - June 15, 1992 Unisan (Bondoc Peninsula), Quezon - August 1987 The Philippine Normal University in Manila, a national state university like PUP, operates the following provincial branches: I. PNU Alicia, Isabela in spite of the presence of the Isabela State University in Echague; 2. -

Student Handbook Development 86 IV

QUALITY POLICY We at Bulacan State University (BulSU) are committed to provide excellent instruction, research and extension services. We shall implement an internationally recognized management system in all aspects of our operations, processes and services in line with our commitment and in achieving our objectives. To continually improve our quality performance and the effectiveness and suitability of our quality management system, we shall: Comply with applicable laws and regulations, the requirements of our stakeholders, industry initiatives and other requirements we subscribe to; Assess the needs of our customers and strive to exceed their expectations; Provide assurance to our students, partners and other stakeholders to quality services by offering excellent instruction, pioneering research, and providing value-adding extension services and responsive engagements; Establish quality objectives aimed at improving the efficiency of our operations, processes and procedures for sustainable growth; and Capacitate our employees and staff to maintain a highly competent, motivated and reliable workforce, thereby ensuring work is performed with excellence. UNDERGRADUATE STUDENT MANUAL OF BULACAN STATE UNIVERSITY BOR Resolution No. 85, Series of 2016 Implemented: A.Y. 2017-2018 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword iv University President’s Message v Brief History of Bulacan State University vi PART I. GENERAL PROVISIONS A. Institutional Philosophy 1 B. Policy Statements 2 C. Classification of Students 2 D. Students Rights, Obligations and Responsibilities 3 E. Obedience to the Laws of the Land 7 F. Students’ Orientation 8 PART II. ACADEMIC REGULATIONS A. Admission Requirement 8 B. Change of Academic Load 13 C. Substitution of Subjects 13 D. Tutorial and Special Classes 13 E. -

11102017 Atbulsu.Pdf

Republic of the Philippines Bulacan State University OFFICE OF ADMISSIONS AND ORIENTATION SERVICES Bulletin of Information Academic Year 2018-2019 ADMISSION POLICY AND GUIDELINES In order to produce highly competent, ethical, and service-oriented professionals through excellent instruction, research and responsive community engagements, entrants to the University are required to qualify for admission based on Grade Point Average (GPA) and the results of the Admission Test Bulacan State University (ATBulSU). A. Qualification of Applicants to ATBulSU 1. For College Freshmen a. Grade 12 candidates for graduation in the current school year b. Grade 12 graduates c. Foreigners who are Grade 12 candidates for graduation or Grade 12 graduates subject to the evaluation of pertinent documents 2. For Grade 7 Elementary graduates with a GPA of 83% in Filipino, English, Math, Science and Makabayan B. Eligibility for Application The applicant or his / her authorized representative (e.g. parents, relatives, guardians, teachers) may file the application in the Office of Admissions and Orientation Services. C. Application Requirements 1. Two (2) pieces recent 2x2 ID picture (White Background) (computer-generated pictures will not be accepted) 2. Non-refundable ATBulSU fee of P300.00 3. One (1) photocopy (and the original for verification purpose only) of any of the following (whichever is applicable) Certificate of Grades / Transcript of Record (TOR) For College Freshmen - Grade 11(1st and 2nd Sem) and Grade 12 (1st Semester) BSIT & BIT 3rd Year - completed -

Tarlac State University Volume No

Issued by the Office of Public Affairs and Information Tarlac State University Volume No. 50 January 2017 BULLETINThe Official Employees’ Publication of Tarlac State University Inching its way to the top… TSU moves up to 4th overall in SUC III Olympics 2016 Ruth Hazel A. Galang Technical Staff, OPAI After years of staying in the middle spot, Tarlac State University reached 3rd runner-up or 4th overall in the recent SUC III Olympics 2016, hosted by the Pampanga State Agricultural University on January 21-27, 2017. 13 State Universities and Colleges competed in this year’s Olympics. Bulacan State University remained on top, holding the overall championship for the past 20 years now. Here are the medal tallies: Ranking SUC Gold Silver Bronze Total 1st BulSU 114 81 59 254 2nd CLSU 67 92 57 216 3rd BPSU 50 34 51 135 4th TSU 23 29 46 98 5th PSAU 19 7 6 32 continue on page 2 271 Januarians march in 28th Com- TSU Faculty Recognized in International LOLITA NEWS mencement Exercises Conferences Page 2 Page 3 Page 4 2 Tarlac State University Tarlac State University 3 Volume No. 50 January 2017 Volume No. 50 January 2017 Issued by the Office Issued by the Office of Public Affairs and of Public Affairs and Information Information BULLETINThe Official Employees’ Publication of Tarlac State University BULLETINThe Official Employees’ Publication of Tarlac State University 271 Januarians march in 28th Commencement Exercises TSU Faculty Recognized in International Conferences Ruth Hazel A. Galang By Dr. Cecilia Liwanag – Calub Technical Staff, OPAI Professor, COEd Tarlac State University bid College of Computer Studies, 34; College farewell to 271 new graduates during the of Public Administration, 4; and the TSU moves up to 4th..