Australia Citylink, Melbourne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Independent Review of the Victorian Ports System: Discussion Paper

Independent review of the Victorian Ports System DISCUSSION PAPER JULY 2020 Department of Transport Authorised by the Victorian Government, Melbourne 1 Spring Street Melbourne Victoria 3000 Telephone (03) 9655 6666 Designed and published by the Department of Transport ISBN 978-0-7311-9179-6 Contact us if you need this information in an accessible format such as large print or audio, please telephone (03) 9655 6666 or email [email protected] © Copyright State of Victoria Department of Transport Except for any logos, emblems, trademarks, artwork and photography this document is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence Contents Minister's Foreword 4 6. Safe operation of the port system 40 Preface 5 6.1. Introduction 40 Abbreviations 6 6.2. Issues and options 42 1. Introduction 7 6.2.1. Harbour Masters 42 1.1. The purpose of the review 7 6.2.2. Pilotage 43 1.2. The review approach 7 6.2.3. Towage 46 1.3. Review process and timing 8 6.2.4. Safety and Environment 47 Management Plans 2. The Victorian Ports System 10 6.2.5. A port safety licensing system 49 2.1. The recent evolution of the system 10 7. Port strategic planning 53 2.2. The system today 12 7.1. Introduction 53 2.2.1. Commercial ports 14 7.2. Issues and options 54 2.2.2. Local ports 15 7.2.1. Port Development Strategies 54 3. A Vision for the Victorian Ports 19 System 7.2.2. A Victorian ports strategy 55 3.1. -

Road Safety Camera Locations in Victoria

ROAD SAFETY CAMERA LOCATIONS IN VICTORIA Approved Sites — April 2006 — Road Safety Camera Locations in Victoria – Location of Road Safety Cameras – Red light only wet film cameras (84 sites) • Armadale, Kooyong Road and Malvern Road • Ascot Vale, Maribyrnong Road and Mt Alexander Road • Balwyn, Balwyn Road and Whitehorse Road • Bayswater, Bayswater Road and Mountain Highway • Bendigo, High Street and Don Street • Bendigo, Myrtle Street and High Street • Box Hill, Canterbury Road and Station Street • Box Hill, Station Street and Thames Street • Brighton, Bay Street and St Kilda Street • Brunswick, Melville Road and Albion Street • Brunswick, Nicholson Street and Glenlyon Road • Bulleen, Manningham Road and Thompsons Road • Bundoora, Grimshaw Street and Marcorna Street • Bundoora, Plenty Road and Settlement Road • Burwood, Highbury Road and Huntingdale Road • Burwood, Warrigal Road and Highbury Road • Camberwell, Prospect Hill Road and Burke Road • Camberwell, Toorak Road and Burke Road • Carlton, Elgin Street and Nicholson Street • Caulfield, Balaclava Road and Kooyong Road • Caulfield, Glen Eira Road and Kooyong Road • Chadstone, Warrigal Road and Batesford Road • Chadstone, Warrigal Road and Batesford Road • Cheltenham, Warrigal Road and Centre Dandenong Road • Clayton, Dandenong Road and Clayton Road • Clayton, North Road and Clayton Road • Coburg, Harding Street and Sydney Road • Collingwood, Johnston Street and Hoddle Street • Corio, Princes Highway and Purnell Road • Corio, Princes Highway and Sparks Road • Dandenong, McCrae Street -

NORTH WEST Freight Transport Strategy

NORTH WEST Freight Transport Strategy Department of Infrastructure NORTH WEST FREIGHT TRANSPORT STRATEGY Final Report May 2002 This report has been prepared by the Department of Infrastructure, VicRoads, Mildura Rural City Council, Swan Hill Rural City Council and the North West Municipalities Association to guide planning and development of the freight transport network in the north-west of Victoria. The State Government acknowledges the participation and support of the Councils of the north-west in preparing the strategy and the many stakeholders and individuals who contributed comments and ideas. Department of Infrastructure Strategic Planning Division Level 23, 80 Collins St Melbourne VIC 3000 www.doi.vic.gov.au Final Report North West Freight Transport Strategy Table of Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... i 1. Strategy Outline. ...........................................................................................................................1 1.1 Background .............................................................................................................................1 1.2 Strategy Outcomes.................................................................................................................1 1.3 Planning Horizon.....................................................................................................................1 1.4 Other Investigations ................................................................................................................1 -

City Link's High-Speed Electronic Tolling

CASE PROGRAM 2007-91.1 City Link’s high-speed electronic tolling (A) The tolling systems went live without a glitch at 1 am Monday the 3rd [of January 2000], a national public holiday. Charges now apply at three toll points located at the Tullamarine section, the elevated roadway between Racecourse and Dynon Roads, and the Bolte Bridge… Although fewer motorists were on the road, demand for e-Tags was strong. Since the 23 December announcement [that tolling would begin 3 January] more than 45,000 e-Tags have been ordered, bringing the total sales to date to almost 400,000. The first day of tolling, CityLink’s 132629 hotline fielded more than 20,000 calls. The continued demand throughout the week prompted Transurban to announce the availability of a second hotline for general enquiries… Transurban Managing Director Kim Edwards said the company was pleased with the recent developments and expressed appreciation for the public’s patience during recent delays. “We are thrilled to deliver the completed Western Link to Melbourne’s motorists, who will now get the full benefit of the project’s leading-edge technology and design,” he said. Extract from: fasttrack, Transurban CityLink executive information newsletter, January 2000. In August 2000, Transurban City Link chief executive Kim Edwards announced that his company’s damages claim against the consortium Transfield-Obayashi Joint Venture (TOJV) for delays and difficulties with the 22-km City Link tollway was ________________________________________________________________ This case was prepared from published information by Susan Keyes-Pearce, MBA 1998 and Professor Michael Vitale of the Centre for Management of Information Technology at the University of Melbourne. -

Citylink Groundwater Management

CASE STUDY CityLink Groundwater Management Aquifer About CityLink Groundwater implications for design and construction A layer of soil or rock with relatively higher porosity CityLink is a series of toll-roads that connect major and permeability than freeways radiating outward from the centre of Design of tunnels requires lots of detailed surrounding layers. This Melbourne. It involved the upgrading of significant geological studies to understand the materials that enables usable quantities stretches of existing freeways, the construction of the tunnel will be excavated through and how those of water to be extracted from it. new roads including a bridge over the Yarra River, materials behave. The behavior of the material viaducts and two road tunnels. The latter are and the groundwater within it impacts the design of Fault zone beneath residential areas, the Yarra River, the the tunnel. A challenge for design beneath botanical gardens and sports facilities where surface suburbs and other infrastructure is getting access A area of rock that has construction would be either impossible or to sites to get that information! The initial design of been broken up due to stress, resulting in one unacceptable. the tunnel was based on assumptions of how much block of rock being groundwater would flow into the tunnel, and how displaced from the other. The westbound Domain tunnel is approximately much pressure it would apply on the tunnel walls They are often associated 1.6km long and is shallow. The east-bound Burnley (Figure 2). with higher permeability than the surrounding rock tunnel is 3.4km long part of which is deep beneath the Yarra River. -

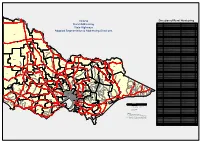

Victoria Rural Addressing State Highways Adopted Segmentation & Addressing Directions

23 0 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 MILDURA Direction of Rural Numbering 0 Victoria 00 00 Highway 00 00 00 Sturt 00 00 00 110 00 Hwy_name From To Distance Bass Highway South Gippsland Hwy @ Lang Lang South Gippsland Hwy @ Leongatha 93 Rural Addressing Bellarine Highway Latrobe Tce (Princes Hwy) @ Geelong Queenscliffe 29 Bonang Road Princes Hwy @ Orbost McKillops Rd @ Bonang 90 Bonang Road McKillops Rd @ Bonang New South Wales State Border 21 Borung Highway Calder Hwy @ Charlton Sunraysia Hwy @ Donald 42 99 State Highways Borung Highway Sunraysia Hwy @ Litchfield Borung Hwy @ Warracknabeal 42 ROBINVALE Calder Borung Highway Henty Hwy @ Warracknabeal Western Highway @ Dimboola 41 Calder Alternative Highway Calder Hwy @ Ravenswood Calder Hwy @ Marong 21 48 BOUNDARY BEND Adopted Segmentation & Addressing Directions Calder Highway Kyneton-Trentham Rd @ Kyneton McIvor Hwy @ Bendigo 65 0 Calder Highway McIvor Hwy @ Bendigo Boort-Wedderburn Rd @ Wedderburn 73 000000 000000 000000 Calder Highway Boort-Wedderburn Rd @ Wedderburn Boort-Wycheproof Rd @ Wycheproof 62 Murray MILDURA Calder Highway Boort-Wycheproof Rd @ Wycheproof Sea Lake-Swan Hill Rd @ Sea Lake 77 Calder Highway Sea Lake-Swan Hill Rd @ Sea Lake Mallee Hwy @ Ouyen 88 Calder Highway Mallee Hwy @ Ouyen Deakin Ave-Fifteenth St (Sturt Hwy) @ Mildura 99 Calder Highway Deakin Ave-Fifteenth St (Sturt Hwy) @ Mildura Murray River @ Yelta 23 Glenelg Highway Midland Hwy @ Ballarat Yalla-Y-Poora Rd @ Streatham 76 OUYEN Highway 0 0 97 000000 PIANGIL Glenelg Highway Yalla-Y-Poora Rd @ Streatham Lonsdale -

Free Tram Zone

Melbourne’s Free Tram Zone Look for the signage at tram stops to identify the boundaries of the zone. Stop 0 Stop 8 For more information visit ptv.vic.gov.au Peel Street VICTORIA ST Victoria Street & Victoria Street & Peel Street Carlton Gardens Stop 7 Melbourne Star Observation Wheel Queen Victoria The District Queen Victoria Market ST ELIZABETH Melbourne Museum Market & IMAX Cinema t S n o s WILLIAM ST WILLIAM l o DOCKLANDS DR h ic Stop 8 N Melbourne Flagstaff QUEEN ST Gardens Central Station Royal Exhibition Building St Vincent’s LA TROBE ST LA TROBE ST VIC. PDE Hospital SPENCER ST KING ST WILLIAM ST ELIZABETH ST ST SWANSTON RUSSELL ST EXHIBITION ST HARBOUR ESP HARBOUR Flagstaff Melbourne Stop 0 Station Central State Library Station VICTORIA HARBOUR WURUNDJERI WAY of Victoria Nicholson Street & Victoria Parade LONSDALE ST LONSDALE ST Stop 0 Parliament Station Parliament Station VICTORIA HARBOUR PROMENADE Nicholson Street Marvel Stadium Library at the Dock SPRING ST Parliament BOURKE ST BOURKE ST BOURKE ST House YARRA RIVER COLLINS ST Old Treasury Southern Building Cross Station KING ST WILLIAM ST ST MARKET QUEEN ST ELIZABETH ST ST SWANSTON RUSSELL ST EXHIBITION ST COLLINS ST SPENCER ST COLLINS ST COLLINS ST Stop 8 St Paul’s Cathedral Spring Street & Collins Street Fitzroy Gardens Immigration Treasury Museum Gardens WURUNDJERI WAY FLINDERS ST FLINDERS ST Stop 8 Spring Street SEA LIFE Melbourne & Flinders Street Aquarium YARRA RIVER Flinders Street Station Federation Square Stop 24 Stop Stop 3 Stop 6 Don’t touch on or off if Batman Park Flinders Street Federation Russell Street Eureka & Queensbridge Tower Square & Flinders Street you’re just travelling in the SkyDeck Street Arts Centre city’s Free Tram Zone. -

Building a Better Victoria

Victorian Budget 2014|15 Building a Better Victoria Budget Overview Contents 01 Budget at a glance 02 Strengthening Victoria’s finances 03 Building a stronger Victorian economy 04 State-shaping infrastructure to build a better Victoria 05 State-shaping infrastructure to build a better Victoria – Rail 08 State-shaping infrastructure to build a better Victoria – Integrating road and rail 09 State-shaping infrastructure to build a better Victoria – Road 10 Victoria’s infrastructure program 12 I nvesting in our future – Boosting skills, education and training 13 Strengthening health care and community services 14 Building a better regional Victoria 16 Building a safer Victoria The Secretary This publication makes reference to the This work, 2014-15 Budget Overview, is Department of Treasury and Finance 2014-15 Budget Paper set which includes: licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 1 Treasury Place Budget Paper No. 1 – Treasurer’s Speech 3.0 Australia licence. You are free to re-use the work under that licence, on the condition that Melbourne Victoria, 3002 Budget Paper No. 2 – Strategy and Outlook you credit the State of Victoria (Department of Australia Budget Paper No. 3 – Service Delivery Treasury and Finance) as author and comply Telephone: +61 3 9651 5111 Budget Paper No. 4 – State Capital Program with the other licence terms. The licence does Facsimile: +61 3 9651 2062 Budget Paper No. 5 – Statement of Finances not apply to any images, photographs or Website: budget.vic.gov.au (incorporating Quarterly Financial Report No. 3) branding, including the Victorian Coat of Arms, the Victorian Government logo and the Authorised by the Victorian Government © State of Victoria 2014 Department of Treasury and Finance logo. -

International Trade Prospectus Welcome

INTERNATIONAL TRADE PROSPECTUS WELCOME As one of the fastest growing areas in Australia, our city represents a new frontier for business growth in Melbourne’s south east. With a population set to exceed 549,000 by 2041 and Our region is centrally located to Victoria’s major activity strong growth likely to continue well into the future, the centres, including Melbourne’s CBD, airport and ports time to invest in our City is now. via key arterial routes within our boundaries. Our City is characterised by strong population growth, These easy connections also offer easy access to the but our competitive advantages, broad growth across beauty of the neighbouring Mornington Peninsula and a range of sectors and business confidence ensure Dandenong Ranges, and the abundant resources of that we have the right mix of conditions to allow your Gippsland. business to thrive. Strong confidence in our region from both the public Given our growth, the City of Casey is committed to and private sectors attracts hundreds of millions in providing conveniences akin to those in major cities, with residential and commercial investments annually, which world-class sporting facilities and community centres presents exciting new opportunities for local businesses enjoyed by all members of the community. to leverage. Considering the region’s city conveniences, award The region’s investors also enjoy pronounced savings winning open spaces and residential estates, it is little from an abundance of affordable, well-serviced and surprise that we are forecast to grow by a further 54% ready-to-develop land, as well as Council’s commitment by 2041. -

Domain Parklands Master Plan 2019-2039 a City That Cares for the Environment

DOMAIN PARKLANDS MASTER PLAN 2019-2039 A CITY THAT CARES FOR THE ENVIRONMENT Environmental sustainability is the basis of all Future Melbourne goals. It requires current generations to choose how they meet their needs without compromising the ability of future generations to be able to do the same. Acknowledgement of Traditional Owners The City of Melbourne respectfully acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the land, the Boon Wurrung and Woiwurrung (Wurundjeri) people of the Kulin Nation and pays respect to their Elders, past and present. For the Kulin Nation, Melbourne has always been an important meeting place for events of social, educational, sporting and cultural significance. Today we are proud to say that Melbourne is a significant gathering place for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. melbourne.vic.gov.au CONTENTS A City That Cares For Its Environment 2 4. Master Plan Themes 23 1. Overview 5 4.1 Nurture a diverse landscape and parkland ecology 23 1.1 Why do we need a master plan? 6 4.2 Acknowledge history and cultural heritage 24 1.2 Vision 7 4.3 Support exceptional visitor experience 28 1.3 Domain Parklands Master Plan Snapshot 8 4.4 Improve people movement and access 32 1.4 Preparation of the master plan 9 4.5 Management and partnerships to build resilience 39 1.5 Community and Stakeholder engagement 10 5. Domain Parklands Precincts Plans 41 2. Domain Parklands 11 5.1 Precinct 1 - Alexandra and Queen Victoria Gardens 42 2.1 The history of the site 11 5.2 Precinct 2 - Kings Domain 43 2.2 The Domain Parklands today 12 5.3 Precinct 3 - Yarra Frontage and Government House 44 2.3 Strategic context and influences 12 5.4 Precinct 4 - Visitor Precinct 45 2.4 Landscape Characters 14 5.5 Precinct 5 - Kings Domain South 46 2.5 Land management and status 15 6. -

Australian Historic Theme: Producers

Stockyard Creek, engraving, J MacFarlane. La Trobe Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria. Gold discoveries in the early 1870s stimulated the development of Foster, initially known as Stockyard Creek. Before the railway reached Foster in 1892, water transport was the most reliable method of moving goods into and out of the region. 4. Moving goods and cargo Providing transport networks for settlers on the land Access to transport for their produce is essential to primary Australian Historic Theme: producers. But the rapid population development of Victoria in the nineteenth century, particularly during the 1850s meant 3.8. Moving Goods and that infrastructure such as good all-weather roads, bridges and railway lines were often inadequate. Even as major roads People were constructed, they were often fi nanced by tolls, adding fi nancial burden to farmers attempting to convey their produce In the second half of the nineteenth century a great deal of to market. It is little wonder that during the 1850s, for instance, money and government effort was spent developing port and when a rapidly growing population provided a market for grain, harbour infrastructure. To a large extent, this development was fruit and vegetables, most of these products were grown linked to efforts to stimulate the economic development of the near the major centres of population, such as near the major colony by assisting the growth of agriculture and settlement goldfi elds or close to Melbourne and Geelong. Farmers with on the land. Port and harbour development was also linked access to water transport had an edge over those without it. -

Viable, Safe, Sustainable and Efficient Road Transport Industry’, My Submission Relates to the Following Items from the Terms of Reference B

Regarding the enquiry for a ‘viable, safe, sustainable and efficient road transport industry’, my submission relates to the following items from the Terms of Reference b. the development and maintenance of road transport infrastructure to ensure a safe and efficient road transport industry; e. the social and economic impact of road-related injury, trauma and death; h. the importance of establishing a formal consultative relationship between the road transport industry and all levels of government in Australia. My concern relates specifically to VicRoads granting permits for road trains and super heavy vehicles to travel from the top end of the state; i.e. Mildura and Robinvale Victoria etc to Melbourne and to Dooen etc along roads that are not designed for these size trucks and without passing lanes for hundreds of kms.. Below I have number of questions that relate to my concerns. What about passing lanes? There are none on the Calder Highway for 350kms from nth Hattah to Ravenswood (sth Bendigo) and the 240kms from nth Hattah to Dooen/Horsham. (involving the Calder, Sunraysia and Henty Highways. What happens with vehicles travelling at different speeds? Imagine a situation where a caravan is cruising at 80km/hr, followed by a road trains at its 90km/hr, followed by B Doubles at 100km/h and then a line of cars at 100km/hr; with north of Wycheproof at 110km/h; Without passing lanes for hundreds of kms it is a terrible risk to the public. Should there be consideration to the fact that the only public transport we have involves the same roads? We do not have a rail public transport system.