Eberhard Hopf Between Germany and the US ∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

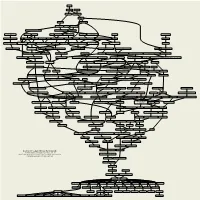

Academic Genealogy of George Em Karniadakis

Nilos Kabasilas Demetrios Kydones Elissaeus Judaeus Manuel Chrysoloras Georgios Plethon Gemistos 1380, 1393 Basilios Bessarion 1436 Mystras Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 1444 Università di Padova Vittorino da Feltre Cristoforo Landino Marsilio Ficino 1416 Università di Padova 1462 Università di Firenze Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Theodoros Gazes Angelo Poliziano Università di Mantova 1433 Constantinople / Università di Mantova 1477 Università di Firenze Leo Outers Alessandro Sermoneta Gaetano da Thiene Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Demetrios Chalcocondyles Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Rudolf Agricola Thomas à Kempis Heinrich von Langenstein 1485 Université Catholique de Louvain 1493 Università di Firenze 1452 Mystras / Accademia Romana 1478 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1363, 1375 Université de Paris Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Pelope Pietro Roccabonella Nicoletto Vernia François Dubois Jean Tagault Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Janus Lascaris Matthaeus Adrianus Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Jan Standonck Alexander Hegius Johannes von Gmunden 1504, 1515 Université Catholique de Louvain Università di Padova Università di Padova 1516 Université de Paris 1499, 1508 Università di Padova 1472 Università di Padova 1477, 1481 Universität Basel / Université de Poitiers 1474, 1490 Collège Sainte-Barbe / Collège de Montaigu 1474 1406 Universität Wien Niccolò Leoniceno Jacobus (Jacques Masson) Latomus Desiderius Erasmus Petrus (Pieter de Corte) Curtius Pietro Pomponazzi Jacobus (Jacques -

Classics in Mathematics Richard Courant· Fritz John Introduction To

Classics in Mathematics Richard Courant· Fritz John Introduction to Calculus and Analysis Volume I Springer-V erlag Berlin Heidelberg GmbH Richard Courant • Fritz John Introd uction to Calculus and Analysis Volume I Reprint of the 1989 Edition Springer Originally published in 1965 by Interscience Publishers, a division of John Wiley and Sons, Inc. Reprinted in 1989 by Springer-Verlag New York, Inc. Mathematics Subject Classification (1991): 26-XX, 26-01 Cataloging in Publication Data applied for Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Courant, Richard: Introduction to calcu1us and analysis / Richard Courant; Fritz John.- Reprint of the 1989 ed.- Berlin; Heidelberg; New York; Barcelona; Hong Kong; London; Milan; Paris; Singapore; Tokyo: Springer (Classics in mathematics) VoL 1 (1999) ISBN 978-3-540-65058-4 ISBN 978-3-642-58604-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-58604-0 Photograph of Richard Courant from: C. Reid, Courant in Gottingen and New York. The Story of an Improbable Mathematician, Springer New York, 1976 Photograph of Fritz John by kind permission of The Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, New York ISSN 1431-0821 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved. whether the whole or part of the material is concemed. specifically the rights of trans1ation. reprinting. reuse of illustrations. recitation. broadcasting. reproduction on microfilm or in any other way. and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted onlyunder the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9.1965. in its current version. and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer-Verlag. Violations are Iiable for prosecution under the German Copyright Law. -

8. Gram-Schmidt Orthogonalization

Chapter 8 Gram-Schmidt Orthogonalization (September 8, 2010) _______________________________________________________________________ Jørgen Pedersen Gram (June 27, 1850 – April 29, 1916) was a Danish actuary and mathematician who was born in Nustrup, Duchy of Schleswig, Denmark and died in Copenhagen, Denmark. Important papers of his include On series expansions determined by the methods of least squares, and Investigations of the number of primes less than a given number. The process that bears his name, the Gram–Schmidt process, was first published in the former paper, in 1883. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J%C3%B8rgen_Pedersen_Gram ________________________________________________________________________ Erhard Schmidt (January 13, 1876 – December 6, 1959) was a German mathematician whose work significantly influenced the direction of mathematics in the twentieth century. He was born in Tartu, Governorate of Livonia (now Estonia). His advisor was David Hilbert and he was awarded his doctorate from Georg-August University of Göttingen in 1905. His doctoral dissertation was entitled Entwickelung willkürlicher Funktionen nach Systemen vorgeschriebener and was a work on integral equations. Together with David Hilbert he made important contributions to functional analysis. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Erhard_Schmidt.jpg ________________________________________________________________________ 8.1 Gram-Schmidt Procedure I Gram-Schmidt orthogonalization is a method that takes a non-orthogonal set of linearly independent function and literally constructs an orthogonal set over an arbitrary interval and with respect to an arbitrary weighting function. Here for convenience, all functions are assumed to be real. un(x) linearly independent non-orthogonal un-normalized functions Here we use the following notations. n un (x) x (n = 0, 1, 2, 3, …..). n (x) linearly independent orthogonal un-normalized functions n (x) linearly independent orthogonal normalized functions with b ( x) (x)w(x)dx i j i , j . -

Writing the History of Dynamical Systems and Chaos

Historia Mathematica 29 (2002), 273–339 doi:10.1006/hmat.2002.2351 Writing the History of Dynamical Systems and Chaos: View metadata, citation and similar papersLongue at core.ac.uk Dur´ee and Revolution, Disciplines and Cultures1 brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector David Aubin Max-Planck Institut fur¨ Wissenschaftsgeschichte, Berlin, Germany E-mail: [email protected] and Amy Dahan Dalmedico Centre national de la recherche scientifique and Centre Alexandre-Koyre,´ Paris, France E-mail: [email protected] Between the late 1960s and the beginning of the 1980s, the wide recognition that simple dynamical laws could give rise to complex behaviors was sometimes hailed as a true scientific revolution impacting several disciplines, for which a striking label was coined—“chaos.” Mathematicians quickly pointed out that the purported revolution was relying on the abstract theory of dynamical systems founded in the late 19th century by Henri Poincar´e who had already reached a similar conclusion. In this paper, we flesh out the historiographical tensions arising from these confrontations: longue-duree´ history and revolution; abstract mathematics and the use of mathematical techniques in various other domains. After reviewing the historiography of dynamical systems theory from Poincar´e to the 1960s, we highlight the pioneering work of a few individuals (Steve Smale, Edward Lorenz, David Ruelle). We then go on to discuss the nature of the chaos phenomenon, which, we argue, was a conceptual reconfiguration as -

Mathematicians Fleeing from Nazi Germany

Mathematicians Fleeing from Nazi Germany Mathematicians Fleeing from Nazi Germany Individual Fates and Global Impact Reinhard Siegmund-Schultze princeton university press princeton and oxford Copyright 2009 © by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Siegmund-Schultze, R. (Reinhard) Mathematicians fleeing from Nazi Germany: individual fates and global impact / Reinhard Siegmund-Schultze. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-12593-0 (cloth) — ISBN 978-0-691-14041-4 (pbk.) 1. Mathematicians—Germany—History—20th century. 2. Mathematicians— United States—History—20th century. 3. Mathematicians—Germany—Biography. 4. Mathematicians—United States—Biography. 5. World War, 1939–1945— Refuges—Germany. 6. Germany—Emigration and immigration—History—1933–1945. 7. Germans—United States—History—20th century. 8. Immigrants—United States—History—20th century. 9. Mathematics—Germany—History—20th century. 10. Mathematics—United States—History—20th century. I. Title. QA27.G4S53 2008 510.09'04—dc22 2008048855 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Sabon Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ press.princeton.edu Printed in the United States of America 10 987654321 Contents List of Figures and Tables xiii Preface xvii Chapter 1 The Terms “German-Speaking Mathematician,” “Forced,” and“Voluntary Emigration” 1 Chapter 2 The Notion of “Mathematician” Plus Quantitative Figures on Persecution 13 Chapter 3 Early Emigration 30 3.1. The Push-Factor 32 3.2. The Pull-Factor 36 3.D. -

Math 126 Lecture 4. Basic Facts in Representation Theory

Math 126 Lecture 4. Basic facts in representation theory. Notice. Definition of a representation of a group. The theory of group representations is the creation of Frobenius: Georg Frobenius lived from 1849 to 1917 Frobenius combined results from the theory of algebraic equations, geometry, and number theory, which led him to the study of abstract groups, the representation theory of groups and the character theory of groups. Find out more at: http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/history/ Mathematicians/Frobenius.html Matrix form of a representation. Equivalence of two representations. Invariant subspaces. Irreducible representations. One dimensional representations. Representations of cyclic groups. Direct sums. Tensor product. Unitary representations. Averaging over the group. Maschke’s theorem. Heinrich Maschke 1853 - 1908 Schur’s lemma. Issai Schur Biography of Schur. Issai Schur Born: 10 Jan 1875 in Mogilyov, Mogilyov province, Russian Empire (now Belarus) Died: 10 Jan 1941 in Tel Aviv, Palestine (now Israel) Although Issai Schur was born in Mogilyov on the Dnieper, he spoke German without a trace of an accent, and nobody even guessed that it was not his first language. He went to Latvia at the age of 13 and there he attended the Gymnasium in Libau, now called Liepaja. In 1894 Schur entered the University of Berlin to read mathematics and physics. Frobenius was one of his teachers and he was to greatly influence Schur and later to direct his doctoral studies. Frobenius and Burnside had been the two main founders of the theory of representations of groups as groups of matrices. This theory proved a very powerful tool in the study of groups and Schur was to learn the foundations of this subject from Frobenius. -

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Emigration Of

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Report No. 51/2011 DOI: 10.4171/OWR/2011/51 Emigration of Mathematicians and Transmission of Mathematics: Historical Lessons and Consequences of the Third Reich Organised by June Barrow-Green, Milton-Keynes Della Fenster, Richmond Joachim Schwermer, Wien Reinhard Siegmund-Schultze, Kristiansand October 30th – November 5th, 2011 Abstract. This conference provided a focused venue to explore the intellec- tual migration of mathematicians and mathematics spurred by the Nazis and still influential today. The week of talks and discussions (both formal and informal) created a rich opportunity for the cross-fertilization of ideas among almost 50 mathematicians, historians of mathematics, general historians, and curators. Mathematics Subject Classification (2000): 01A60. Introduction by the Organisers The talks at this conference tended to fall into the two categories of lists of sources and historical arguments built from collections of sources. This combi- nation yielded an unexpected richness as new archival materials and new angles of investigation of those archival materials came together to forge a deeper un- derstanding of the migration of mathematicians and mathematics during the Nazi era. The idea of measurement, for example, emerged as a critical idea of the confer- ence. The conference called attention to and, in fact, relied on, the seemingly stan- dard approach to measuring emigration and immigration by counting emigrants and/or immigrants and their host or departing countries. Looking further than this numerical approach, however, the conference participants learned the value of measuring emigration/immigration via other less obvious forms of measurement. 2892 Oberwolfach Report 51/2011 Forms completed by individuals on religious beliefs and other personal attributes provided an interesting cartography of Italian society in the 1930s and early 1940s. -

Implications for Understanding the Role of Affect in Mathematical Thinking

Mathematicians and music: Implications for understanding the role of affect in mathematical thinking Rena E. Gelb Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2021 © 2021 Rena E. Gelb All Rights Reserved Abstract Mathematicians and music: Implications for understanding the role of affect in mathematical thinking Rena E. Gelb The study examines the role of music in the lives and work of 20th century mathematicians within the framework of understanding the contribution of affect to mathematical thinking. The current study focuses on understanding affect and mathematical identity in the contexts of the personal, familial, communal and artistic domains, with a particular focus on musical communities. The study draws on published and archival documents and uses a multiple case study approach in analyzing six mathematicians. The study applies the constant comparative method to identify common themes across cases. The study finds that the ways the subjects are involved in music is personal, familial, communal and social, connecting them to communities of other mathematicians. The results further show that the subjects connect their involvement in music with their mathematical practices through 1) characterizing the mathematician as an artist and mathematics as an art, in particular the art of music; 2) prioritizing aesthetic criteria in their practices of mathematics; and 3) comparing themselves and other mathematicians to musicians. The results show that there is a close connection between subjects’ mathematical and musical identities. I identify eight affective elements that mathematicians display in their work in mathematics, and propose an organization of these affective elements around a view of mathematics as an art, with a particular focus on the art of music. -

Professor Richard Courant (1888 – 1972)

Professor Richard Courant (1888 – 1972) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Courant Field: Mathematics Institutions: University of Göttingen University of Münster University of Cambridge New York University Alma mater: University of Göttingen Doctoral advisor: David Hilbert Doctoral students: William Feller Martin Kruskal Joseph Keller Kurt Friedrichs Hans Lewy Franz Rellich Known for: Courant number Courant minimax principle Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy condition Biography: Courant was born in Lublinitz in the German Empire's Prussian Province of Silesia. During his youth, his parents had to move quite often, to Glatz, Breslau, and in 1905 to Berlin. He stayed in Breslau and entered the university there. As he found the courses not demanding enough, he continued his studies in Zürich and Göttingen. Courant eventually became David Hilbert's assistant in Göttingen and obtained his doctorate there in 1910. He had to fight in World War I, but he was wounded and dismissed from the military service shortly after enlisting. After the war, in 1919, he married Nerina (Nina) Runge, a daughter of the Göttingen professor for Applied Mathematics, Carl Runge. Richard continued his research in Göttingen, with a two-year period as professor in Münster. There he founded the Mathematical Institute, which he headed as director from 1928 until 1933. Courant left Germany in 1933, earlier than many of his colleagues. While he was classified as a Jew by the Nazis, his having served as a front-line soldier exempted him from losing his position for this particular reason at the time; however, his public membership in the social-democratic left was a reason for dismissal to which no such exemption applied.[1] After one year in Cambridge, Courant went to New York City where he became a professor at New York University in 1936. -

Kailash C. Misra Rutgers University, New Brunswick

Nilos Kabasilas Heinri%h von )angenstein ;emetrios Ky2ones 4lissae"s J"2ae"s Universit> 2e /aris (1060) ,eorgios /lethon ,emistos Johannes von ,m"n2en !an"el Chrysoloras (10'5) UniversitIt *ien (1.56) ,"arino 2a ?erona $asilios $essarion ,eorg von /e"erba%h (1.5') !ystras (1.06) UniversitIt *ien (1..5) Johannes 8rgyro1o"los Johannes !Lller Regiomontan"s )"%a /a%ioli UniversitC 2i /a2ova (1...) UniversitIt )ei1Big : UniversitIt *ien (1.-6) ?ittorino 2a Aeltre !arsilio Ai%ino ;omeni%o !aria Novara 2a Aerrara Cristo3oro )an2ino UniversitC 2i /a2ova (1.16) UniversitC 2i AirenBe (1.6() UniversitC 2i AirenBe (1.'0) Theo2oros ,aBes 9gnibene (9mnibon"s )eoni%en"s) $onisoli 2a )onigo 8ngelo /oliBiano Constantino1le : UniversitC 2i !antova (1.00) UniversitC 2i !antova UniversitC 2i AirenBe (1.66) ;emetrios Chal%o%on2yles R"2ol3 8gri%ola S%i1ione Aortig"erra )eo 9"ters ,aetano 2a Thiene Sigismon2o /ol%astro Thomas C Kem1is Ja%ob ben Jehiel )oans !oses /ereB !ystras : 8%%a2emia Romana (1.-() UniversitC 2egli St"2i 2i Aerrara (1.6') UniversitC 2i AirenBe (1.90) Universit> CatholiK"e 2e )o"vain (1.'-) Jan"s )as%aris Ni%oletto ?ernia /ietro Ro%%abonella Jan Stan2on%& 8le7an2er Hegi"s Johann (Johannes Ka1nion) Re"%hlin AranNois ;"bois ,irolamo (Hieronym"s 8lean2er) 8lean2ro !aarten (!artin"s ;or1i"s) van ;or1 /elo1e !atthae"s 82rian"s Jean Taga"lt UniversitC 2i /a2ova (1.6() UniversitC 2i /a2ova UniversitC 2i /a2ova CollMge Sainte@$arbe : CollMge 2e !ontaig" (1.6.) (1.6.) UniversitIt $asel : Universit> 2e /oitiers (1.66) Universit> 2e /aris (1-16) UniversitC -

Chapter 2. Vectors and Vector Spaces

2.2. Cartesian Coordinates and Geometrical Properties of Vectors 1 Chapter 2. Vectors and Vector Spaces Section 2.2. Cartesian Coordinates and Geometrical Properties of Vectors Note. There is a natural relationship between a point in Rn and a vector in n R . Both are represented by an n-tuple of real numbers, say (x1, x2, . , xn). In sophomore linear algebra, you probably had a notational way to distinguish vectors in Rn from points in Rn. For example, Fraleigh and Beauregard in Linear Algebra, n 3rd Edition (1995), denote the point x ∈ R as (x1, x2, . , xn) and the vector n ~x ∈ R as ~x = [x1, x2, . , xn]. Gentle makes no such notational convention so we will need to be careful about how we deal with points and vectors in Rn, when these topics are together. Of course, there is a difference between points in Rn and vectors in Rn (a common question on the departmental Linear Algebra Comprehensive Exams)!!! For example, vectors in Rn can be added, multiplied by scalars, they have a “direction” (an informal concept based on existence of an ordered basis and the component of the vector with respect to that ordered basis). But vectors don’t have any particular “position” in Rn and they can be translated from one position to another. Points in Rn do have a specific position given by the coordinates of the point. But you cannot add points, multiply them be scalars, and they have neither magnitude nor direction. So the properties which a vector in Rn has are not shared by a point in Rn and vice-versa. -

Zermelo in Z¨Urich

Zermelo in Zurich¨ ¤ Volker Peckhaus Institut fur¨ Philosophie der Universitat¨ Erlangen-Nurnberg¨ Bismarckstr. 1, D – 91054 Erlangen E-mail: [email protected] 1 Einleitung Meine sehr geehrten Damen und Herren! Unter dem eher lapidaren Titel Zerme- ” lo in Zurich“¨ mochte¨ ich eine Periode aus dem Leben des Logikers und Mengen- theoretikers Ernst Zermelo beleuchten, die zwar die Krone seiner verungluckten¨ akademischen Karriere darstellt, von der aber gleichwohl bisher kaum etwas be- kannt war. Was bekannt ist, und zwar wohl jedem, der sich schon einmal mit der Biographie Zermelos beschaftigt¨ hat, ist eine Anekdote, die Abraham A. Fraenkel in seiner Autobiographie Lebenskreise erzahlt.¨ Ich mochte¨ Ihnen die Fußnote, in der er sich mit Zermelo beschaftigt,¨ vollstandig¨ zitieren (1967, 149, Fn. 55): Obgleich nicht hierher gehorig,¨ seien von diesem genialen und seltsamen Mathematiker, dessen Namen bis heute einen fast magischen Klang behalten hat, einige kaum bekannte Zuge¨ berichtet. Ein schlechter Lehrer, kam er in Gottingen¨ nicht vorwarts,¨ obgleich er 1904 einen drei Seiten langen Aufsatz — Beweis des Wohlordnungsgesetzes“ — publizierte, der die gesamte ma- ” thematische Welt in — zustimmende und ablehnende — Aufregung versetz- te; mit seinen Gegnern setzte er sich 1908 in einer Abhandlung auseinander, die an Sarkasmus nicht ihresgleichen in der mathematischen Literatur hat. 1910 wurde er endlich als Ordinarius an die kantonale Universitat¨ Zurich¨ be- rufen. Kurz vor dem Weltkrieg verbrachte er eine Nacht in den bayerischen Alpen und fullte¨ im Meldezettel des Hotels die Rubrik Staatsangehorigkeit“¨ ” mit den Worten aus: Gottseidank kein Schweizer.“ Das Ungluck¨ wollte, daß ” kurz danach der Leiter des Unterrichtsdepartments des Kantons Zurich¨ im gleichen Hotel wohnte und die Eintragung sah.