Tullochgorum Haydn — Scottish Songs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DIJOUS, 1 DE MARÇ DEL 2018 Voces Huelgas

PROGRAMACIÓ DE CATALUNYA MÚSICA DIJOUS, 1 DE MARÇ DEL 2018 Voces Huelgas. Dir.: Luis Lozano. (5m) 07:00 BUTLLETÍ DE NOTÍCIES STRAUSS, RICHARD: Suite n. 1 de l'òpera "El cavaller de la rosa", Titulars a la nostra mida. Posem l'accent a la informació cultural. TrV 227c. Orquestra Filharmònica Txeca. Dir.: Vladimir Ashkenazy. 07:03 TOTS ELS MATINS DEL MÓN (14m) ...són camins sense retorn. Un paradís de músiques per començar el SIBELIUS, JEAN: Concert per a violí i orquestra en re m, op. 47. dia de la millor manera. Presentat per Joan Vives i Ester Pinart. Maxim Vengerov, violí. Orquestra Simfònica de Chicago. Dir.: Daniel Barenboim. 08:00 BUTLLETÍ DE NOTÍCIES (33m) Titulars a la nostra mida. Posem l'accent a la informació cultural. MALIPIERO, GIAN FRANCESCO: "Simfonia in un tempo" per a orquestra. Orquestra Simfònica de Moscou. 09:00 BUTLLETÍ I AGENDA Dir.: Antonio de Almeida. (27m) Titulars a la nostra mida. Informació cultural i agenda de Catalunya Música. 16:00 AGENDA 11:00 ELS CONCERTS Informació cultural i agenda de Catalunya Música. Una selecció dels millors concerts de la nostra fonoteca. Presentació d'Olga Cardús. 16:03 ELS CONCERTS FESTIVAL INTERNACIONAL D'ORGUE DE MONTSERRAT 2017 Una selecció dels millors concerts de la nostra fonoteca. Presentació Johann Sebastian Bach: Preludi i fuga en Do BWV 545, ''Jesu, meine de Maria Montes. Zuversicht'' ( Jesús, la meva confiança), preludi coral, BWV 728. Antoni Soler: Sonata per a teclat n. 54 en Do ''de clarins''. Miquel TEMPORADA DE CONCERTS “LA MÚSICA DEL MUSEU”, 2017- López: Cinc versos de mig registre per a orgue. -

The Lochaber Royal National Mòd 2017

Agenda Item 5(b) Report RES/53b/17 No HIGHLAND COUNCIL Committee: Corporate Resources Committee Date: November 17th 2017 Report Title: The Lochaber Royal National Mòd 2017 Report By: Area Care & Learning Manager West Area ( Lead for Gaelic) Gaelic Development Officer 1. Purpose/Executive Summary 1.1 The purpose of the report is to:- • inform Members on the Royal National Mòd Loch Abar which took place between 13th- 21st October 2017. • to seek approval to begin to plan for future Royal National Mòds which will take place in the Highland Council area after 2020. 2. Recommendations 2.1 Members are asked to: i. to note the positive impact of the Royal National Mòd in the Lochaber area. ii. approve early work on securing the Royal National Mòd to the Highland Council area beyond 2020. 3. An Comunn Gàidhealach (ACG) 3.1 An Comunn Gàidhealach (ACG) is the organisation responsible for running the Royal National Mòd. ACG establishes the Local Organising Committee (LOC) in the area where the Mòd takes place. 4 Mòd Loch Abar 4.1 On October 13th Mòd Loch Abar commenced with a torchlight street parade led by the Deputy First Minister which departed from Cameron Square in Fort William High Street to the Nevis Centre, where the Official Opening Ceremony took place 4.2 Elected Members were present at the Torchlight Parade and the Opening Ceremony. The Chairperson of Corporate Resources Committee welcomed the Mòd to Lochaber on behalf of the Highland Council, The Deputy First Minister gave the keynote address. The Mòd was officially opened by Kate Forbes MSP. -

Clanci Livingstone32-33

Broj / Issue 32-33 Prosinac - December 2008 / Siječanj - January 2009 Godina / Year III Hrvatski / English Croatian magazine for quality of life dvobroj | double issue y 2009 Godina / Year III y 2009 Godina / Year Photosafari Pogled u 2009. A View Into 2009 Broj / Issue 32-33 Prosinac - December 2008 Siječanj Januar Ljiljana M. Pandža: Interview Emil Tedeschi Branimir Pofuk: Sting i Karamazov u Zagrebu Sting & Karamazov in Zagreb Grgo Zečić: Moda željna moći STONE Fashion’s Craving for Power 29,00 KN / 4,5 EUR LIVING SADRŽAJ TABLE OF CONTENTS PROSINAC2008.|SIJEČANJ2009.DECEMBER2008|JANUARY2009 08 14 52 90 96 122 08 Jedan dan... | One day... - Damir Konestra 58 Prosperov kantun | Prosperov’s Corner 90 Egzotično putovanje | Exotic Travels 122 LivingStyle - Jakša Fiamengo U carstvu vještica - Slobodan Prosperov Novak - Želimir Černelić Portali intime In the kingdom of witches Shakespeareov zadarski Falstaff Zemlja ledena, a ljudi sretni Portals of innermost feelings Postojimnogozanimljivihnačinazaulazakunovu Shakespeare’s Falstaff from Zadar Icy country, happy people Akosuočiprozoriduše,ajesu,analognotomu, godinu,adruženjesvješticamanavrhuKleka ImaliShakespeareovradvezesHrvatskom? prozorisuočijednekuće zasigurnojejedanodzanimljivijih Dakakodaima 96 LivingSpace - Damir Konestra Ifeyesarethewindowstothesoul,andtheycerta- Therearelotsofinterestingwaystoenterthenew DoesShakespeare’sworkhaveanyconnecti- Hrvatski hramovi sporta i arhitekture inlyare,thewindowsare,byanalogy,theeyesofa year,andhangingoutwithwitchesonKlekpeak onwithCroatia?Ofcourseitdoes -

Edin Karamazov (HR)

Edin Karamazov (HR) Četrtek / Thursday, 13.8.15, 20:30 Kostanjevica na Krki, Nekdanji cistercijanski samostan Former Cistercian Monastery Petek / Friday, 14.8.15, 20:30 Celje, Stara grofija / Old Counts' Mansion Johann Sebastian Bach Izvirna glasba za violino in čelo v priredbi za lutnjo Original violin & original cello music transcribed for the lute Transkripcije, predelave, transpozicije in priredbe so bile del baročnega glasbenega življenja in Bach je bil z njimi dobro seznanjen. Njegov sodobnik je dejal, da je Bach na primer igral Sonate in partite za solo violino na čembalo, pri čemer je dodal toliko harmonije ali basov, kot se mu je zdelo potrebno. Poleg tega imamo primere Bachovih priredb tako tujih kot lastnih skladb. Bach torej za lutnjo ni pisal novih del posebej za ta instrument, temveč je predeloval svoje skladbe, ki so že obstajale, v druge oblike. Edin Karamazov si tako ne prizadeva, da bi neskončno dokazoval, da so takoimenovane Bachove skladbe za lutnjo zares izvorno namenjene za ta instrument, temveč raje vzame dela za solo violino ali čelo in jih spremeni v nove skladbe za lutnjo. Pri tem se (kolikor je možno) drži izvirnih zapisov, glasbene namembnosti, fraziranja in artikulacije, a jih hkrati priredi na Iz sredstev davkoplačevalcev sofinancirajo festival Seviqc Brežice 2015 / The lutnji lasten način, tako da so prijetne za igranje in poslušanje. Seviqc Brežice Festival 2015 is co-financed from taxpayer funds by: AECID - Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional para el Desarrollo (Madrid, ES), EACEA - Education, -

IAIN Mclachlan an Island Heritage

IAIN McLACHLAN An Island Heritage Traditional Music of the Western Isles IAIN McLACHLAN, Traditional Musician. Born: 21 setting’ or ‘a Skye setting’ of such and such a reel. His October, 1927, in Hacklett, Benbecula. Died: 21 February father played melodeon for local dances and Iain learned 1995 in Creagorry, Benbecula, aged 67. melodeon from him. While still a boy, Iain used to sit at the knee of a local retired fiddle teacher and dancing WITH THE death of Iain McLachlan in 1995, Scottish master, Donald MacPhee (of Nunton, Benbecula), one traditional music lost one of its finest exponents. Known of the few Hebridean fiddlers of that era, and from him particularly for his masterly touch on the three-row he learned many old fiddle tunes and the old style of Shand Morino button accordion, Iain also played pipes, playing them. fiddle and melodeon and had an extensive knowledge I first remember hearing Iain in a broadcast record- of traditional music. For more than 40 years he had trav- ing made by Fred Macaulay for the Gaelic Department elled by road and ferry to play the accordion at ceilidhs of the BBC. Iain was playing the great pipe tune The and dances throughout the Highlands and Islands. In the Marchioness of Tullibardine on accordion in duet with words of his great friend, fellow button-box player and the piper Roddie Macaulay, of the Creagorry Hotel, play- ceilidh-band leader, Fergie MacDonald, of Acharacle: “I’ve ing chanter. It was such a remarkable sound I resolved lost a truly great friend, but Iain was also the greatest there and then to bring Iain McLachlan to the Kinross three-row button-box player in the Highlands and Islands Festival, which at that time I was involved in organising. -

Princess Margaret of the Isles Memorial Prize for Senior Clàrsach, 16 June 2018 Finallist Biographies and Programme Notes

Princess Margaret of the Isles Memorial Prize for Senior Clàrsach, 16 June 2018 Finallist biographies and programme notes Màiri Chaimbeul is a Boston, Massachusetts-based harp player and composer from the Isle of Skye. Described by Folk Radio UK as "astonishing", she is known for her versatile sound, which combines deep roots in Gaelic tradition with a distinctive improvising voice and honed classical technique. Màiri tours regularly throughout the UK, Europe and in North America. Recent highlights include performances at major festivals and events including the Cambridge Folk Festival, Fairport's Cropredy Convention, Hillside Festival (Canada), WGBH's St Patrick's Day Celtic Sojourn, Celtic Connections, and Encuentro Internacional Maestros del Arpa, Bogota, Colombia. Màiri can currently be heard regularly in duo with US fiddler Jenna Moynihan, progressive-folk Toronto group Aerialists, with her sister Brìghde Chaimbeul, and with legendary violinist Darol Anger & the Furies. She is featured in series 2 of Julie Fowlis and Muireann NicAmhlaoibh's BBC Alba/TG4 television show, Port. Màiri was twice- nominated for the BBC Radio 2 Young Folk Award, finalist in the BBC Young Traditional & Jazz Musicians of the year and twice participated in Savannah Music Festival's prestigious Acoustic Music Seminar. She is a graduate of the Berklee College of Music, where she attended with full scholarship, and was awarded the prestigious American Roots Award. Màiri joins the faculty at Berklee College of Music this year as their lever harp instructor. Riko Matsuoka was born in the Osaka prefecture of Japan and began playing the piano at the age of three. She started playing the harp at the age of fourteen. -

Abstracts with Names Arne Anderdal and Jo Asgeir Lie

Abstracts with Names Arne Anderdal and Jo Asgeir Lie RUNDDANS MUSIC ON HARDANGER FIDDLE The Hardanger fiddle is a string instrument with four top strings and four or five sympathetic strings. The instrument emerged during the 1600s, and was used to play dance music and ceremonial music in duple and triple meter; this music was transferred from other instruments. This music and dance are still very widespread. From the late 1700s to the end of the 1800s, dances and music which were termed runddans came to Norway from Europe and became established as an important part of the popular repertoire in the country. There are many different versions of these dances, but the main types are vals, polka, masurka, and reinlender. Runddans music was played on fiddle and Hardanger fiddle, as well as on instruments such as diatonic and chromatic button accordion. When Norway became an independent state in 1905, the country was to be constructed using “old”, authentic Norwegian culture, and in this context runddans music was regarded as too modern to be used as a building block. The oldest forms of music were given highest status, even though Hardanger fiddlers also played runddans music. In recent times, there has been a conviction that almost no runddans music existed in several of the areas where Hardanger fiddle has been used. But if one investigates historical records and archives, a great deal of runddans music that has a Hardanger fiddle style can be found. This confirms that a great variety of music was played on Hardanger fiddle. What was the effect of the ideological use of folk music on the music world in Norway during the period leading up to 1940? Pat Ballantyne SCOTTISH DANCING MASTERS: PUTTING A KILT ON IT This paper considers the role of Scottish dancing masters in the adoption of new dances in nineteenth- and early twentieth century Scotland. -

Step Dancing in Cape Breton and Scotland: Contrasting Contexts and Creative Processes

Step Dancing in Cape Breton and Scotland: Contrasting Contexts and Creative Processes MATS MELIN Abstract: This article briefly outlines the migration of percussive step dancing to Cape Breton Island from the Scottish Highlands in the 19th century and the introduction of this dance genre to Scotland from Cape Breton in the 1990s. I reflect on the changes to the dance genre in Cape Breton and to the understanding of step dancing in Scotland, particularly on a visual and kinaesthetic level, as the reference 40 (1): 35-56. 40 (1): points and the guiding support of a step dance community do not exist in Scotland as they do in Cape Breton. MUSICultures Résumé : Cet article décrit brièvement la migration de la danse à claquettes faisant percussion depuis les Highlands d’Écosse à l’Île du Cap-Breton au 19e siècle, puis le retour de ce genre de danse en Écosse depuis le Cap-Breton dans les années 1990. Je réfléchis aux changements qu’a connus cette danse au Cap- Breton et à la manière dont on conçoit la danse à claquettes en Écosse, plus particulièrement aux niveaux visuel et kinesthésique, car il n’existe pas en Écosse, contrairement à l’Île du Cap-Breton, de points de référence et de lignes directrices pouvant soutenir une communauté de danse à claquettes. This article has accompanying videos on our YouTube channel. You can find them on the playlist for MUSICultures volume 40, issue 1, available here: bit.ly/MUSICultures-40-1. With the ephemerality of web-based media in mind, we warn you that our online content may not always be accessible, and we apologize for any inconvenience. -

Alan Curtis Anna Netrebko Und Elīna Garanča Magdalena Kožená Jonas

www.klassikakzente.de • C 43177 • 2 • 2009 Alan Curtis EXklusiv: die Zukunft der HÄndel-oper Anna Netrebko und Elīna Garanča DAS Bellini-Traumduo Magdalena Kožená Neuland Vivaldi Jonas Kaufmann Sehnsuchtsvoll Die GROSSEN bei 442 8746 442 9924 JETZT NEU! 480 1218 zum Händel-Jubiläum 480 1862 Limitierte Sondereditionen für kluge Sammler 442 9701 480 1226 476 8761 JETZT NEU! zum Haydn-Jubiläumy 480 1898 www.klassikakzente.de www.eloquence-klassik.de AZ_Eloquence-Boxen_A4.indd 1 30.03.2009 15:39:32 Uhr Editorial Foto: Felix Broede INTRO 4 Dom-Jubiläum in Mainz • Alice Sara Ott live Gewinnen Sie eine Reise nach Tallinn 90 Jahre Bauhaus Andreas Kluge TiTEL 6 Jonas Kaufmann: Wagner cantabile Liebe Musikfreundin, lieber Musikfreund, die Zeiten werden härter. In der Tat. Trotzdem sollte, wie leider in MAGAZIN der Politik nur allzu häufig praktiziert, der budgetäre Rotstift nicht 10 Magdalena Kožená: primär und ausschließlich bei der Kultur angesetzt werden. Nicht Terra fast incognita in der Politik, nicht in den privaten Haushalten. Denn immerhin 12 Joseph Haydn: Die hohe Kunst des leistete und leistet die Musik zu allen Zeiten einen nicht unwe- subtilen Humors sentlichen Beitrag zur ausgeglichenen Gemütsverfassung ihrer 14 Yuja Wang: Die junge Löwin Hörerinnen und Hörer. Shakespeare lässt seinen Lucentio in 16 Hermann Prey: Der EU-Sänger „Der Widerspenstigen Zähmung“ rhetorisch fragen: „Ich wider- 17 Anna Netrebko und Elīna Garanča: sinniger Tropf, der nicht begriff, zu welchem Zweck Musik uns Strahlen, leuchten, mischen ward gegeben! Ist‘s nicht, des Menschen Seele zu erfrischen 18 Alan Curtis über die Zukunft der Händel-Oper nach ernstem Studium und der Arbeit Müh?“ Und Napoleon 20 Arvo Pärt: Gipfel und Wellentäler Bonaparte – man glaubt es kaum! – resümierte einmal: „Die 21 Der klassische Fragebogen, Musik hat von allen Künsten den tiefsten Einfluss auf das Gemüt. -

Clarsach Programme Notes Final

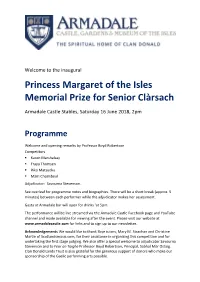

Welcome to the inaugural Princess Margaret of the Isles Memorial Prize for Senior Clàrsach Armadale Castle Stables, Saturday 16 June 2018, 2pm Programme Welcome and opening remarks by Professor Boyd Robertson Competitors ▪ Karen Marshalsay ▪ Fraya Thomsen ▪ Riko Matsuoka ▪ Màiri Chaimbeul Adjudicator: Savourna Stevenson. See overleaf for programme notes and biographies. There will be a short break (approx. 5 minutes) between each performer while the adjudicator makes her assessment. Gasta at Armadale bar will open for drinks ‘at 5pm. The performance will be live streamed via the Armadale Castle Facebook page and YouTube channel and made available for viewing after the event. Please visit our website at www.armadalecastle.com for links and to sign up to our newsletter. Acknowledgements We would like to thank Skye tutors, Mary M. Strachan and Christine Martin of Scotlandsmusic.com, for their assistance in organising this competition and for undertaking the first stage judging. We also offer a special welcome to adjudicator Savourna Stevenson and to Fear an Taighe Professor Boyd Robertson, Principal, Sabhal Mòr Ostaig. Clan Donald Lands Trust is also grateful for the generous support of donors who make our sponsorship of the Gaelic performing arts possible. Programme notes Candidates were required to prepare a 25 minute recital, including a variety of traditional and contemporary Scottish styles, and a new composition by themselves. The following notes have been provided by the performers. Karen Marshalsay Opening with a tune from a Skye collection, and featuring my own compositions alongside others written for harp, pipes and fiddle, and a tune from one of the oldest published collections of Highland music, this recital aims to convey both the traditional and contemporary nature of Scottish music on the harp. -

Paganelli HOPE Adam Smith and the Scottish Enlightenment With

Recent Engagements with Adam Smith and the Scottish Enlightenment by Maria Pia Paganelli CHOPE Working Paper No. 2015-06 June 2015 Recent Engagements with Adam Smith and the Scottish Enlightenment Maria Pia Paganelli Trinity University [email protected] Forthcoming, History of Political Economy, 2015 Abstract Recent literature on Adam Smith and other 18th Scottish thinkers shows an engaged conversation between the Scots and today’s scholars in the sciences that deal with humans—social sciences, humanities, as well as neuroscience and evolutionary psychology. We share with the 18th century Scots preoccupations about understanding human beings, human nature, sociability, moral development, our ability to understand nature and its possible creator, and about the possibilities to use our knowledge to improve our surrounding and standards of living. As our disciplines evolve, the studies of Smith and Scottish Enlightenment evolve with them. Smith and the Scots remain our interlocutors. Keywords: adam smith, david hume, scottish enlightenment, recent literature JLE: A1; A12; A13; A14; B1; B3; B30; B31; B4; B40; B41; C9; C90 1 Forthcoming, History of Political Economy, 2015 Recent Engagements with Adam Smith and the Scottish Enlightenment 1 Maria Pia Paganelli David Levy once told me: “Adam Smith is still our colleague. He's not in the office but he's down the hall.” Recent literature on Adam Smith and the Scottish Enlightenment shows Levy right. At the time of writing, searching Econlit peer review journal articles for “Adam Smith” in the abstract gives 480 results since year 2000. Opening the search to Proquest gives 1870 results since 2000 (see Appendix 2 to get a rough sense of the size of recent literature). -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. ‘Great Gathering of the Clans’: Scottish Clubs and Scottish Identity in Scotland and America, c.1750-1832 Sarah Elizabeth McCaslin Doctor of Philosophy The University of Edinburgh 2015 i Continue, Best of Clubs, Long to Improve Your native Plains and gain your nation’s Love - Allan Ramsay, ‘The Pleasures of Improvments in Agriculture’, (c.1723). I declare that this thesis (consisting of approximately 93,500 words) is entirely my own work and has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification, or published in any form. Sarah Elizabeth McCaslin 15 August 2014 ii ABSTRACT The eighteenth century witnessed the proliferation of voluntary associations throughout the British-Atlantic world. These voluntary associations consisted of groups of men with common interests, backgrounds, or beliefs that were willing to pool their resources in order to achieve a common goal.