Hatching of Sod Webworm Eggs in Relation to Low and High Temperatures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society

JOURNAL OF THE LEPIDOPTERISTS' SOCIETY Volume 38 1984 Number 3 Joumal of the Lepidopterists' Society 38(3). 1984. 149-164 SOD WEBWORM MOTHS (PYRALIDAE: CRAMBINAE) IN SOUTH DAKOTA B. McDANIEL,l G. FAUSKEl AND R. D. GUSTIN 2 ABSTRACT. Twenty-seven species of the subfamily Crambinae known as sod web worm moths were collected from South Dakota. A key to species has been included as well as their distribution patterns in South Dakota. This study began after damage to rangeland in several South Dakota counties in the years 1974 and 1975. Damage was reported from Cor son, Dewey, Harding, Haakon, Meade, Perkins, Stanley and Ziebach counties. An effort was made to determine the species of Crambinae present in South Dakota and their distribution. Included are a key for species identification and a list of species with their flight periods and collection sites. MATERIALS AND METHODS Black light traps using the General Electric Fluorescent F ls T8 B1 15 watt bulb were set up in Brookings, Jackson, Lawrence, Minnehaha, Pennington and Spink counties. In Minnehaha County collecting was carried out with a General Electric 200 watt soft-glow bulb. Daytime collecting was used in several localities. Material in the South Dakota State University Collection was also utilized. For each species a map is included showing collection localities by county. On the maps the following symbols are used: • = collected by sweepnet. Q = collected by light trap. Key to South Dakota Cram binae 1a. Rs stalked .__ ... ___ .. __ ......................... _..... _ ................................. _._............................................. 2 lb. Rs arising directly from discal cell ................................................................. _............ _............ -

Great Lakes Entomologist

- Vol. 3'3, No.3 & 4 Fall/Winter 2000 THE GREAT LAKES ENTOMOLOGIST PUBLISHED BY THE MICHIGAN ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY THE GREAT LAKES ENTOMOLOGIST Published by the Michigan Entomological Society Volume 33 No. 3-4 ISSN 0090-0222 TABLE OF CONTENTS New distribution record for the endangered crawling water beetle, Brychius hungerfordi (Coleoptera: Haliplidael ond notes on seasonal abundance and food preferences Michael Grant, Robert Vande Kopple and Bert Ebbers . ............... 165 Arhyssus hirtus in Minnesota: The inland occurrence of an east coast species (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: RhopalidaeJ John D. Laftin and John Haarstad .. 169 Seasonol occurrence of the sod webworm moths (lepidoptera: Crambidoe) of Ohio Harry D. Niemczk, David 1. Shetlar, Kevin T. Power and Douglas S. Richmond. ... 173 Leucanthiza dircella (lepidoptera: Gracillariidae): A leafminer of leatherwood, Dirca pa/us/tis Toby R. Petriee, Robert A Haack, William J. Mattson and Bruce A. Birr. 187 New distribution records of ground beetles from the north-central United States (Coleoptera: Carabidae) Foster Forbes Purrington, Daniel K. Young, Kirk 1. lorsen and Jana Chin-Ting lee .......... 199 Libel/ula flavida (Odonata: libellulidoe], a dragonfly new to Ohio Tom D. Schultz. ... 205 Distribution of first instar gypsy moths [lepidoptera: Lymantriidae] among saplings of common Great Lakes understory species 1. l. and J. A. Witter ....... 209 Comparison of two population sampling methods used in field life history studies of Mesovelia mulsonti (Heteroptera: Gerromorpha: Mesoveliidae) in southern Illinois Steven J. Taylor and J. E McPherson ..... .. 223 COVER PHOTO Scudderio furcata Brunner von Wattenwyl (Tettigoniidae], the forktailed bush katydid. Photo taken in Huron Mountains, MI by M. F. O'Brien. -

Additions, Deletions and Corrections to An

Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society No. 36 (2012) ADDITIONS, DELETIONS AND CORRECTIONS TO AN ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE IRISH BUTTERFLIES AND MOTHS (LEPIDOPTERA) WITH A CONCISE CHECKLIST OF IRISH SPECIES AND ELACHISTA BIATOMELLA (STAINTON, 1848) NEW TO IRELAND K. G. M. Bond1 and J. P. O’Connor2 1Department of Zoology and Animal Ecology, School of BEES, University College Cork, Distillery Fields, North Mall, Cork, Ireland. e-mail: <[email protected]> 2Emeritus Entomologist, National Museum of Ireland, Kildare Street, Dublin 2, Ireland. Abstract Additions, deletions and corrections are made to the Irish checklist of butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera). Elachista biatomella (Stainton, 1848) is added to the Irish list. The total number of confirmed Irish species of Lepidoptera now stands at 1480. Key words: Lepidoptera, additions, deletions, corrections, Irish list, Elachista biatomella Introduction Bond, Nash and O’Connor (2006) provided a checklist of the Irish Lepidoptera. Since its publication, many new discoveries have been made and are reported here. In addition, several deletions have been made. A concise and updated checklist is provided. The following abbreviations are used in the text: BM(NH) – The Natural History Museum, London; NMINH – National Museum of Ireland, Natural History, Dublin. The total number of confirmed Irish species now stands at 1480, an addition of 68 since Bond et al. (2006). Taxonomic arrangement As a result of recent systematic research, it has been necessary to replace the arrangement familiar to British and Irish Lepidopterists by the Fauna Europaea [FE] system used by Karsholt 60 Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society No. 36 (2012) and Razowski, which is widely used in continental Europe. -

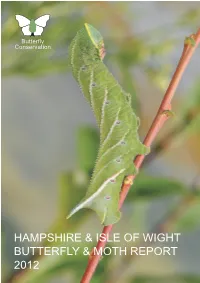

Hampshire & Isle of Wight Butterfly & Moth Report 2012

Butterfly Conservation HAMPSHIRE & ISLE OF WIGHT BUTTERFLY & MOTH REPORT 2012 B Hampshire & Isle of Wight Butterfly & Moth Report, 2012 Editorial team: Paul Brock, Tim Norriss and Mike Wall Production Editors: Mike Wall (with the invaluable assistance of Dave Green) Co-writers: Andy Barker, Linda Barker, Tim Bernhard, Rupert Broadway, Andrew Brookes, Paul Brock, Phil Budd, Andy Butler, Jayne Chapman, Susan Clarke, Pete Durnell, Peter Eeles, Mike Gibbons, Brian Fletcher, Richard Levett, Jenny Mallett, Tim Norriss, Dave Owen, John Ruppersbery, Jon Stokes, Jane Vaughan, Mike Wall, Ashley Whitlock, Bob Whitmarsh, Clive Wood. Database: Ken Bailey, David Green, Tim Norriss, Ian Thirlwell, Mike Wall Webmaster: Robin Turner Butterfly Recorder: Paul Brock Moth Recorders: Hampshire: Tim Norriss (macro-moths and Branch Moth Officer), Mike Wall (micro-moths); Isle of Wight: Sam Knill-Jones Transect Organisers: Andy Barker, Linda Barker and Pam Welch Flight period and transect graphs: Andy Barker Photographs: Colin Baker, Mike Baker, Andy & Melissa Banthorpe, Andy Butler, Tim Bernhard, John Bogle, Paul Brock, Andy Butler, Jayne Chapman, Andy Collins, Sue Davies, Peter Eeles, Glynne Evans, Brian Fletcher, David Green, Mervyn Grist, James Halsey, Ray and Sue Hiley, Stephen Miles, Nick Montegriffo, Tim Norriss, Gary Palmer, Chris Pines, Maurice Pugh, John Ruppersbery, John Vigay, Mike Wall, Fred Woodworth, Russell Wynn Cover Photographs: Paul Brock (Eyed Hawk-moth larva) and John Bogle (Silver- studded Blue) Published by the Hampshire and Isle of Wight Branch of Butterfly Conservation, 2013 Butterfly Conservation is a charity registered in England & Wales (254937) and in Scotland (SCO39268). Registered Office: Manor Yard, East Lulworth, Wareham, Dorset, BH20 5QP The opinions expressed by contributors do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of Butterfly Conservation. -

Program Book

NORTH CENTRAL BRANCH ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF AMERICA TH 68 ANNUAL MEETING PRESIDENT: BILLY FULLER BEST WESTERN RAMKOTA HOTEL 2111 N. LACROSSE STREET RAPID CITY, SD 57701 SPECIAL THANKS TO OUR MEETING SPONSORS CONTENTS Meeting Logistics .......................................................... 2 2013 NCB Meeting Organizers ...................................... 5 2012-13 NCB-ESA Officers and Committees ................. 7 2012 NCB Award Recipients ........................................ 10 Sunday, June 16, 2013 Day at a Glance .............................................. 24 Scientific Sessions .......................................... 25 Monday, June 17, 2013 Day at a Glance .............................................. 27 Scientific Sessions .......................................... 29 Tuesday, June 18, 2013 Day at a Glance ............................................... 52 Scientific Sessions ........................................... 53 Wednesday, June 19, 2013 Day at a Glance ............................................... 64 Scientific Sessions ........................................... 65 Author Index ............................................................... 70 Taxonomic Index ......................................................... 79 Map of Meeting Facilities ............................................ 85 CONTENTS REGISTRATION All participants must register for the meeting. Registration badges are required for admission to all conference functions. The meeting registration desk is located in the foyer area of -

Andrew Sheltz Babylon Junior-Senior High School

Biodiversity of Moths on Long Island Authors: Matthew Ficken, Ryan Marrone, Ian Watral Abstract: Moths are a part of the insect order Lepidoptera which they share with Mentor: Andrew Sheltz butterflies. Moths are an excellent organism to barcode due to the large amount of unclassified moth species, as well as the difficulty trying to identify different Babylon Junior-Senior High School species. The goals of this project are to determine the specific species of moths found around the town of Babylon, and to compare the species of the moths found at different locations around Long Island. To do this moths will be collected from various locations then sequenced according to BLI Protocol. The result will then be compared to achieve the projects goals. After the conclusion of the sequencing process, 8 of the samples were successfully sequenced. Out of the 8 samples, there were 6 different species. This shows that the moth population in Babylon is diverse. It would be beneficial to continue this experiment with a larger sample size to learn more about the biodiversity. Introduction: Moths are a part of the insect order Lepidoptera which they share with butterflies. They are flying insects that begin their lives as caterpillars, consume large amounts of plant matter, and then use this abundance of plant matter to metamorphose into moths. Moths are very similar to butterflies, but can usually Figure 4: Gel electrophoresis of samples indicating which PCR was successful be differentiated by their antennae. Moths are mostly nocturnal, while there are a enough for samples to be sequences (red = unable to be sequenced, green = able few species that are diurnal, such as the bordered straw (Heliothis peltigera). -

Chorion Characteristics of Sod Webworm Eggs

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications: Department of Entomology Entomology, Department of 1-1972 Chorion Characteristics of Sod Webworm Eggs Ellis L. Matheny Jr. University of Tennessee E. A. Heinrichs University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/entomologyfacpub Part of the Entomology Commons Matheny, Ellis L. Jr. and Heinrichs, E. A., "Chorion Characteristics of Sod Webworm Eggs" (1972). Faculty Publications: Department of Entomology. 892. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/entomologyfacpub/892 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Entomology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications: Department of Entomology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Annals of the Entomological Society of America 65:1 (January 1972), pp. 238–246; doi: 10.1093/aesa/65.1.238 Copyright © 1972 Entomological Society of America. Published by Oxford University Press. Used by permission. Submitted May 3, 1971; published January 17, 1972. Chorion Characteristics of Sod Webworm1 Eggs2 Ellis L. Matheny, Jr.,3 and E. A. Heinrichs4 Department of Agricultural Biology, University of Tennesee Agricultural Experiment Station, Knoxville, Tennessee, USA Abstract The egg chorion was investigated for 15 species of sod webworm moths (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae: Crambinae) collected in Tennessee. Liquid plastic was used for surface printing of chorion sculptur- ing. Scanning electron micrographs were utilized in construction of a taxonomic key to eggs of the Crambinae species studied and the characteristics illustrated. Most sod webworm species lay eggs that are similar in appearance to those of other species and difficult to separate taxonomically. -

Download Download

Index to Volume 118 Compiled by Leslie Cody Abies balsamea, 46,95,124,251,268,274,361,388,401,510,530 confines, 431 lasiocarpa, 191,355,584 thomsoni, 431 Abrostola urentis, 541 Agelaius phoeniceus, 201 Acanthopteroctetes bimaculata, 532 Agelaius phoeniceus, Staging in Eastern South Dakota, Spring Acanthopteroctetidae, 532 Dispersal Patterns of Red-winged Blackbirds, 201 Acasis viridata, 539 Aglais milberti, 537 Acer,52 Agonopterix gelidella, 533 negundo, 309 Agriphila ruricolella, 536 rubrum, 41,96,136,136,251,277,361,508 vulgivagella, 536 saccharinum, 41,124,251 Agropyron spp., 400,584 saccharum, 361,507 cristatum, 300 spicatum, 362 pectiniforme, 560 Achigan à grande bouche, 523 repens, 300 à petite bouche, 523 sibiricum, 560 Achillea millefolium, 166 Agrostis sp., 169 Achnatherum richardsonii, 564 filiculmis, 558 Acipenser fulvescens, 523 gigantea, 560 Acipenseridae, 523 Aira praecox, 177 Acleris albicomana, 534 Aix sponsa, 131,230 britannia, 534 Alaska, Changes in Loon (Gavia spp.) and Red-necked Grebe celiana, 534 (Podiceps grisegena) Populations in the Lower Mata- emargana, 535 nuska-Susitna Valley, 210 forbesana, 534 Alaska, Interactions of Brown Bears, Ursus arctos, and Gray logiana, 534 Wolves, Canis lupus, at Katmai National Park and Pre- nigrolinea, 535 serve, 247 obligatoria, 534 Alaska, Seed Dispersal by Brown Bears, Ursus arctos,in schalleriana, 534 Southeastern, 499 variana, 534 Alaska, The Heather Vole, Genus Phenacomys, in, 438 Acorn, J.H., Review by, 468 Alberta: Distribution and Status, The Barred Owl, Strix varia Acossus -

Hampshire & Isle of Wight Butterfly & Moth Report 2013

Butterfly Conservation HAMPSHIRE & ISLE OF WIGHT BUTTERFLY & MOTH REPORT 2013 Contents Page Introduction – Mike Wall 2 The butterfly and moth year 2013 – Tim Norriss 3 Branch reserves updates Bentley Station Meadow – Jayne Chapman 5 Magdalen Hill Down – Jenny Mallett 8 Yew Hill – Brian Fletcher 9 Dukes on the Edge – Dan Hoare 11 Reflections on Mothing – Barry Goater 13 Brown Hairstreak – Henry Edmunds 18 Obituary: Tony Dobson – Mike Wall 19 Hampshire & Isle of Wight Moth Weekend 2013 – Mike Wall 21 Common Species Summary 24 Branch photographic competition 26 Alternative Mothing – Tim Norriss 28 Great Butterfly Race 2013 – Lynn Fomison 29 Weather report 2013 – Dave Owen 30 Glossary of terms 32 Butterfly report 2013 33 Butterfly record coverage 2013 33 Summary of earliest-latest butterfly sightings 2013 34 2012-2013 butterfly trends in Hampshire & Isle of Wight 35 Species accounts 36 Moth report 2013 72 Editorial 72 Moth record coverage 2013 73 Species accounts 74 List of observers 146 Index to Butterfly Species Accounts 152 1 Introduction I have pleasure in writing this, my first introduction as Chairman of the Branch. When I joined Butterfly Conservation some ten years ago, as a new recruit to the wonderful world of moths, I never envisaged becoming part of the main committee let alone finding myself on this ‘lofty perch’! Firstly, I would like to register my and the Branch’s thanks to Pete Eeles for his support and enthusiasm for the branch during his time as chair, despite the pressures of a job that often saw him away from the country, and to the other members of the main committee for their support and enthusiasm over the past twelve months. -

Crambidae: Lepidoptera) of Ohio: Characterization, Host Associations and Revised Species Accounts

Crambinae (Crambidae: Lepidoptera) of Ohio: Characterization, Host Associations and Revised Species Accounts THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Devon A Rogers Graduate Program in Entomology The Ohio State University 2014 Master's Examination Committee: Dr. David J. Shetlar - Advisor Dr. Steve Passoa Dr. Andy Michel Dr. Dave Gardiner Copyright by Devon Ashley Rogers 2014 Abstract A review of the North American Crambinae sod webworm taxonomy, phylogenetic history, and biology is presented. Traditional analysis, combined with modern genetic analysis has changed and solidified the placement of these species. Previously cryptic and unidentifiable larvae were identified using genetic analysis of the mitochondrial CO1 gene and an evaluation of potential host plant associations is given. DNA sequencing is a useful tool that can be used to identify unknown sod webworm larvae, including the especially difficult to identify first and second instar larvae. Only Parapediasia teterrella larvae were recovered from the short-cut, golf course-type, creeping bentgrass (Agrostis stolonifera), as was a single Agriphila ruricolella. Fissicrambus mutabilis was obtained from lawn-height Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis) and turf type tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea). Sod webworm adults were monitored with a standard blacklight trap between 2009 and 2013. Each year 14 species were recovered from the light trap. Species obtained from the managed turfgrass yielded only a fraction of the number of species attracted to the light trap. The sod webworm species Euchromius ocellus first appeared in late 2012. This is a first report for this species in Ohio. -

Lepidoptera of the Lowden Springs Conservation Area, Alberta, 2002-2006

LEPIDOPTERA OF THE LOWDEN SPRINGS CONSERVATION AREA, ALBERTA, 2002-2006 Charles Durham Bird, 24 April 2007 Box 22, Erskine, AB, T0C 1G0 [email protected] Native grasses, Prairie Crocus and Three-flowered Avens; Lowden Springs Conservation Area, looking ENE towards Lowden Lake, June 3, 2004. THE AREA The Lowden Springs Conservation Area is located on the northwest side of Lowden Lake, 17 km south of Stettler. It was officially dedicated 13 June 2003. It is jointly owned by the Alberta Conservation Association (ACA), Ducks Unlimited Canada (DU) and Nature Conservancy Canada. It comprises 121 acres of native grassland, 5 acres of aspen and 4 acres of alkaline wetlands. The coordinates in the center of the area are 52.09N and 112.425W and the elevation there is 830 m. Historically, the land was part of the Randon Ranch and was grazed for pasture. Small upland portions were broken up many years ago and the native vegetation was destroyed, however, much of the area still has the original native vegetation as indicated by the presence of plants like Prairie Crocus (Pulsatilla ludoviciana) and Three-flowered Avens (Geum triflorum). 2 A stand of Silver Willow and Buckbrush in the middle of the Lowden Springs Natural Area, 4 June 2004 At the dedication, the writer was encouraged to carry out an inventory of the Lepidoptera of the area. He was especially interested in doing so as he was endeavoring to document the species found in natural areas in south-central Alberta and none of the other areas being researched had as much native grassland. -

Phylogeny, Character Evolution and Species Diversity in Crambinae, Heliothelinae and Scopariinae

Phylogeny, character evolution and species diversity in Crambinae, Heliothelinae and Scopariinae DISSERTATION zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades DOCTOR RERUM NATURALIUM (Dr. rer. nat.) vorgelegt dem Bereich Mathematik und Naturwissenschaften der Technischen Universit¨at Dresden von M. Sc. Th´eo Antonin Baptiste L´eger geboren am 02.01.1989 in Lausanne, Schweiz eingereicht am 10. Januar 2020 Die Dissertation wurde in der Zeit von 09/2014 bis 12/2019 an den Senckenberg Naturhistorischen Sammlungen Dresden angefertigt. ii Charles Darwin, letter to T. H. Huxley, 26 September 1857 Darwin Correspondence Project, “Letter no. 2143”, https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/DCP-LETT-2143.xml 1. Gutachter 2. Gutachter Prof. Dr. Christoph Neinhuis Prof. Dr. Niklas Wahlberg Lehrstuhl f¨ur Botanik, Systematic Biology Group Fakult¨at Mathematik und Faculty of Science Naturwissenschaften Lund University Technische Universit¨at Dresden S¨olvegatan 37, Lund Dresden, Deutschland Schweden Declaration Erkl¨arung gem¨aß § 5.1.5 der Promotionsordnung Hiermit versichere ich, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit ohne unzul¨assigeHilfe Dritter und ohne Benutzung anderer als der angegebenen Hilfsmittel angefertigt habe; die aus fremden Quellen direkt oder indirektubernommenen ¨ Gedanken sind als solche kenntlich gemacht. Die Arbeit wurde bisher weder im Inland noch im Ausland in gleicher oder ¨ahnlicher Form einer anderen Pr¨ufungsbeh¨orde vorgelegt. Berlin, 14. Januar 2020 Th´eo L´eger iii iv Acknowledgements This work would not have been possible without the help and support from various people. I want to express my sincere gratitude to Matthias Nuss and Bernard Landry for introducing me to the fabulous group that represent Pyraloidea and to the thrilling field of research that is systematics.