Chinese Children's Experiences of Biliteracy Learning in Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Report of Proceedings

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL — 5 February 1986 565 OFFICIAL REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 5 February 1986 The Council met at half-past Two o'clock PRESENT HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR (PRESIDENT) SIR EDWARD YOUDE, G.C.M.G., M.B.E. THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF SECRETARY SIR DAVID AKERS-JONES, K.B.E., C.M.G., J.P. THE HONOURABLE THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY SIR JOHN HENRY BREMRIDGE, K.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE THE ATTORNEY GENERAL MR. MICHAEL DAVID THOMAS, C.M.G., Q.C. THE HONOURABLE LYDIA DUNN, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHEN SHOU-LUM, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE PETER C. WONG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ERIC PETER HO, C.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR TRADE AND INDUSTRY DR. THE HONOURABLE HO KAM-FAI, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALLEN LEE PENG-FEI, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE HU FA-KUANG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-CHUEN, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JOHN JOSEPH SWAINE, O.B.E., Q.C., J.P. THE HONOURABLE STEPHEN CHEONG KAM-CHUEN, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG YAN-LUNG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS. SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARIA TAM WAI-CHU, O.B.E., J.P. DR. THE HONOURABLE HENRIETTA IP MAN-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN NAI-KEONG, C.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR LANDS AND WORKS THE HONOURABLE CHAN YING-LUN, J.P. -

Towards Chinese Calligraphy Zhuzhong Qian

Macalester International Volume 18 Chinese Worlds: Multiple Temporalities Article 12 and Transformations Spring 2007 Towards Chinese Calligraphy Zhuzhong Qian Desheng Fang Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl Recommended Citation Qian, Zhuzhong and Fang, Desheng (2007) "Towards Chinese Calligraphy," Macalester International: Vol. 18, Article 12. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl/vol18/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute for Global Citizenship at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Macalester International by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Towards Chinese Calligraphy Qian Zhuzhong and Fang Desheng I. History of Chinese Calligraphy: A Brief Overview Chinese calligraphy, like script itself, began with hieroglyphs and, over time, has developed various styles and schools, constituting an important part of the national cultural heritage. Chinese scripts are generally divided into five categories: Seal script, Clerical (or Official) script, Regular script, Running script, and Cursive script. What follows is a brief introduction of the evolution of Chinese calligraphy. A. From Prehistory to Xia Dynasty (ca. 16 century B.C.) The art of calligraphy began with the creation of Chinese characters. Without modern technology in ancient times, “Sound couldn’t travel to another place and couldn’t remain, so writings came into being to act as the track of meaning and sound.”1 However, instead of characters, the first calligraphy works were picture-like symbols. These symbols first appeared on ceramic vessels and only showed ambiguous con- cepts without clear meanings. -

The Web That Has No Weaver

THE WEB THAT HAS NO WEAVER Understanding Chinese Medicine “The Web That Has No Weaver opens the great door of understanding to the profoundness of Chinese medicine.” —People’s Daily, Beijing, China “The Web That Has No Weaver with its manifold merits … is a successful introduction to Chinese medicine. We recommend it to our colleagues in China.” —Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Chinese Medicine, Beijing, China “Ted Kaptchuk’s book [has] something for practically everyone . Kaptchuk, himself an extraordinary combination of elements, is a thinker whose writing is more accessible than that of Joseph Needham or Manfred Porkert with no less scholarship. There is more here to think about, chew over, ponder or reflect upon than you are liable to find elsewhere. This may sound like a rave review: it is.” —Journal of Traditional Acupuncture “The Web That Has No Weaver is an encyclopedia of how to tell from the Eastern perspective ‘what is wrong.’” —Larry Dossey, author of Space, Time, and Medicine “Valuable as a compendium of traditional Chinese medical doctrine.” —Joseph Needham, author of Science and Civilization in China “The only approximation for authenticity is The Barefoot Doctor’s Manual, and this will take readers much further.” —The Kirkus Reviews “Kaptchuk has become a lyricist for the art of healing. And the more he tells us about traditional Chinese medicine, the more clearly we see the link between philosophy, art, and the physician’s craft.” —Houston Chronicle “Ted Kaptchuk’s book was inspirational in the development of my acupuncture practice and gave me a deep understanding of traditional Chinese medicine. -

Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (Ii): the Battle Over "The People" and the Business Community in the Transition to Chinese Rule

HONG KONG'S ENDGAME AND THE RULE OF LAW (II): THE BATTLE OVER "THE PEOPLE" AND THE BUSINESS COMMUNITY IN THE TRANSITION TO CHINESE RULE JACQUES DELISLE* & KEVIN P. LANE- 1. INTRODUCTION Transitional Hong Kong's endgame formally came to a close with the territory's reversion to Chinese rule on July 1, 1997. How- ever, a legal and institutional order and a "rule of law" for Chi- nese-ruled Hong Kong remain works in progress. They will surely bear the mark of the conflicts that dominated the final years pre- ceding Hong Kong's legal transition from British colony to Chinese Special Administrative Region ("S.A.R."). Those endgame conflicts reflected a struggle among adherents to rival conceptions of a rule of law and a set of laws and institutions that would be adequate and acceptable for Hong Kong. They unfolded in large part through battles over the attitudes and allegiance of "the Hong Kong people" and Hong Kong's business community. Hong Kong's Endgame and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule ("Endgame I") focused on the first aspect of this story. It examined the political struggle among members of two coherent, but not monolithic, camps, each bound together by a distinct vision of law and sover- t Special Series Reprint: Originally printed in 18 U. Pa. J. Int'l Econ. L. 811 (1997). Assistant Professor, University of Pennsylvania Law School. This Article is the second part of a two-part series. The first part appeared as Hong Kong's End- game and the Rule of Law (I): The Struggle over Institutions and Values in the Transition to Chinese Rule, 18 U. -

Title of Thesis Or Dissertation, Worded

“USING THE PEAK OF THE FIVE ELDERS AS A BRUSH”: A CALLIGRAPHIC SCREEN BY JUNG HYUN-BOK (1909-1973) by HAN ZHU A THESIS Presented to the Department of Art History and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 2012 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Han Zhu Title: “Using the Peak of the Five Elders as a Brush”: A Calligraphic Screen by Jung Hyun-bok (1909-1973) This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of Art History by: Charles Lachman Chairperson Akiko Walley Member Yugen Wang Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research & Innovation/Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2012 ii © 2012 Han Zhu iii THESIS ABSTRACT Han Zhu Master of Arts Department of Art History June 2012 Title: “Using the Peak of the Five Elders as a Brush”: A Calligraphic Screen by Jung Hyun-bok (1909-1973) Korean calligraphy went through tremendous changes during the twentieth century, and Jung Hyun-bok (1909-1973), a gifted calligrapher, played an important role in bringing about these changes. This thesis focuses on one of Jung’s most mature and refined works, “Using the Peak of the Five Elders as a Brush,” owned by the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art. In addition to translating and explicating the poems on the screen, through a close examination of both the form and content of the work I explore how it reflects Jung’s values, intentions, and background. -

Lady General Hua Mulan (1964)

Open Journal of Social Sciences, 2016, 4, 55-61 Published Online April 2016 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/jss http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jss.2016.44008 Praises of Household Happiness in Social Turmoil: Lady General Hua Mulan (1964) Yuan Tian Department of General Education, Macau University of Science and Technology, Macau, China Received 17 March 2016; accepted 16 April 2016; published 19 April 2016 Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract The relationship between film and culture can be seen from the adaptations that historical fiction films make on these original ancient stories or literary works under the influence of concurrent cultural contexts. In other words, these films are always used to reflect and react on the times in which they are made, instead of the past in which they are set. Therefore film makers add abun- dant up-to-date elements into traditional stories and constantly explore new ways of narration, an effort that turns their productions into live records of certain social and historical periods, com- bining macro and micro approaches to cultural backgrounds, both audible and visual. Pinning on this new angle of reviewing the old days, this paper aims to uncover the identity crisis of Hong Kong residents under the mutual influence of nostalgia and rebellious ideas in the 1960s recon- structed in the Huangmei Opera film Lady General Hua Mulan (1964) together with the analysis of the social historical reasons hidden behind. -

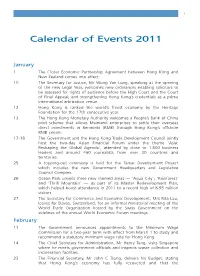

Calendar of Events 2011

i Calendar of Events 2011 January 1 The Closer Economic Partnership Agreement between Hong Kong and New Zealand comes into effect. 10 The Secretary for Justice, Mr Wong Yan Lung, speaking at the opening of the new Legal Year, welcomes new ordinances enabling solicitors to be assessed for rights of audience before the High Court and the Court of Final Appeal; and strengthening Hong Kong’s credentials as a prime international arbitration venue. 12 Hong Kong is ranked the world’s freest economy by the Heritage Foundation for the 17th consecutive year. 13 The Hong Kong Monetary Authority welcomes a People’s Bank of China pilot scheme that allows Mainland enterprises to settle their overseas direct investments in Renminbi (RMB) through Hong Kong’s offshore RMB centre. 17-18 The Government and the Hong Kong Trade Development Council jointly host the two-day Asian Financial Forum under the theme ‘Asia: Reshaping the Global Agenda’, attended by close to 1 800 business leaders and around 460 journalists from over 30 countries and territories. 25 A topping-out ceremony is held for the Tamar Development Project which includes the new Government Headquarters and Legislative Council Complex. 26 Ocean Park unveils three new themed areas — ‘Aqua City’, ‘Rainforest’ and ‘Thrill Mountain’ — as part of its Master Redevelopment Plan, which helped boost attendance in 2011 to a record high of 6.95 million visitors. 27 The Secretary for Commerce and Economic Development, Mrs Rita Lau, leaves for Davos, Switzerland, for an informal ministerial meeting of the World Trade Organisation hosted by the Swiss Government on the sidelines of the annual World Economic Forum meetings. -

The Impacts of Modernity on Family Structure and Function : a Study Among Beijing, Hong Kong and Yunnan Families

Lingnan University Digital Commons @ Lingnan University Theses & Dissertations Department of Sociology and Social Policy 1-1-2012 The impacts of modernity on family structure and function : a study among Beijing, Hong Kong and Yunnan families Ting CAO Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/soc_etd Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons Recommended Citation Cao, T. (2012). The impacts of modernity on family structure and function: A study among Beijing, Hong Kong and Yunnan families (Doctoral dissertation, Lingnan University, Hong Kong). Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.14793/soc_etd.29 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Sociology and Social Policy at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Terms of Use The copyright of this thesis is owned by its author. Any reproduction, adaptation, distribution or dissemination of this thesis without express authorization is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. THE IMPACTS OF MODERNITY ON FAMILY STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION: A STUDY AMONG BEIJING, HONG KONG AND YUNNAN FAMILIES CAO TING PHD LINGNAN UNIVERSITY 2012 THE IMPACTS OF MODERNITY ON FAMILY STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION: A STUDY AMONG BEIJING, HONG KONG AND YUNNAN FAMILIES by CAO Ting A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Social Sciences (Sociology) LINGNAN UNIVERSITY 2012 ABSTRACT The Impacts of Modernity on Family Structure and Function: a Study among Beijing, Hong Kong, and Yunnan Families by CAO Ting Doctor of Philosophy For a generation in many sociological literatures, China has provided the example of traditional family with good intra-familial relationship, filial piety and extended family support which is unusually stable and substantially unchanged. -

Chapter 6 Hong Kong

CHAPTER 6 HONG KONG Key Findings • The Hong Kong government’s proposal of a bill that would allow for extraditions to mainland China sparked the territory’s worst political crisis since its 1997 handover to the Mainland from the United Kingdom. China’s encroachment on Hong Kong’s auton- omy and its suppression of prodemocracy voices in recent years have fueled opposition, with many protesters now seeing the current demonstrations as Hong Kong’s last stand to preserve its freedoms. Protesters voiced five demands: (1) formal with- drawal of the bill; (2) establishing an independent inquiry into police brutality; (3) removing the designation of the protests as “riots;” (4) releasing all those arrested during the movement; and (5) instituting universal suffrage. • After unprecedented protests against the extradition bill, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam suspended the measure in June 2019, dealing a blow to Beijing which had backed the legislation and crippling her political agenda. Her promise in September to formally withdraw the bill came after months of protests and escalation by the Hong Kong police seeking to quell demonstrations. The Hong Kong police used increasingly aggressive tactics against protesters, resulting in calls for an independent inquiry into police abuses. • Despite millions of demonstrators—spanning ages, religions, and professions—taking to the streets in largely peaceful pro- test, the Lam Administration continues to align itself with Bei- jing and only conceded to one of the five protester demands. In an attempt to conflate the bolder actions of a few with the largely peaceful protests, Chinese officials have compared the movement to “terrorism” and a “color revolution,” and have im- plicitly threatened to deploy its security forces from outside Hong Kong to suppress the demonstrations. -

FEFF 23 Will Be Taking Place in Udine and Online from Thursday 24 June to Friday 2 July

2 3 PRESS RELEASES FILM STILLS & FESTIVAL PICS VIDEOS TO DOWNLOAD FROM WWW.FAREASTFILM.COM PRESS AREA Press Office/Far East Film Festival 20 Gianmatteo Pellizzari & Ippolita Nigris Cosattini +39/347/0950890 [email protected] - [email protected] 4 24 June/2 July 2021 - Udine, Italy, Visionario & Cinema Centrale FAR EAST FILM FESTIVAL 23: MOVING FORWARD! 63 titles from 11 countries and regions: the proof of a cinema industry that is back on its feet and looking to the future. FEFF 23 will be taking place in Udine and online from Thursday 24 June to Friday 2 July. Press release for 9 June, 2021 For immediate publication/release UDINE – A throwdown is when you get knocked to the ground. It's an action, and even more a state of mind, that inspired one of Johnnie To's masterpieces and which perfectly captures the dynamics - social, political, health and emotional - of the last year and a half. There's no need to go over why - what we need, what we really need, is to stay focused on the "after" part. The action, and even more so the state of mind, that every throw down triggers: that instinct to get back up. The instinct to not stay down there, where the body blows of history have made us fall. That's the idea - we might even call it the operational philosophy - behind the Far East Film Festival 23: documenting the “after”. Showing a world, the world of Asian cinema, which refuses to resign itself to immobility and is intent on getting back on its feet again.. -

The Cultural Politics of Tobacco Control in Hong Kong

Lingnan University Digital Commons @ Lingnan University Theses & Dissertations Department of Cultural Studies 2009 Beyond public health : the cultural politics of tobacco control in Hong Kong Wai Yin CHAN Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/cs_etd Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Health Policy Commons, and the Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons Recommended Citation Chan, W. Y. (2009).Beyond public health : the cultural politics of tobacco control in Hong Kong (Doctor's thesis, Lingnan University, Hong Kong). Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.14793/cs_etd.4 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Cultural Studies at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Terms of Use The copyright of this thesis is owned by its author. Any reproduction, adaptation, distribution or dissemination of this thesis without express authorization is strictly prohibited. All rights reserved. BEYOND PUBLIC HEALTH: THE CULTURAL POLITICS OF TOBACCO CONTROL IN HONG KONG CHAN WAI YIN PHD LINGNAN UNIVERSITY 2009 BEYOND PUBLIC HEALTH: THE CULTURAL POLITICS OF TOBACCO CONTROL IN HONG KONG by CHAN Wai Yin A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Studies Lingnan University 2009 ABSTRACT Beyond Public Health: The Cultural Politics of Tobacco Control in Hong Kong by CHAN Wai Yin Doctor of Philosophy This work provides cultural and political explanations on how and why cigarette smoking has increasingly become an object of intolerance and control in Hong Kong. -

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL-15 July 1987 2027

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL-15 July 1987 2027 OFFICIAL REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 15 July 1987 The Council met at half-past Two o’clock PRESENT HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR (PRESIDENT) SIR DAVID CLIVE WILSON, K.C.M.G. THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF SECRETARY MR. DAVID ROBERT FORD, L.V.O., O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY (Acting) MR. JOHN FRANCIS YAXLEY, J.P. THE HONOURABLE THE ATTORNEY GENERAL MR. MICHAEL DAVID THOMAS, C.M.G., Q.C. THE HONOURABLE LYDIA DUNN, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHEN SHOU-LUM, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE PETER C. WONG, C.B.E., J.P. DR. THE HONOURABLE HO KAM-FAI, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALLEN LEE PENG-FEI, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE HU FA-KUANG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG PO-YAN, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-CHUEN, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE STEPHEN CHEONG KAM-CHUEN, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG YAN-LUNG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS. SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARIA TAM WAI-CHU, O.B.E., J.P. DR. THE HONOURABLE HENRIETTA IP MAN-HING, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN YING-LUN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS. RITA FAN HSU LAI-TAI, J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS. PAULINE NG CHOW MAY-LIN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE PETER POON WING-CHEUNG, M.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE YEUNG PO-KWAN, C.P.M., J.P.