Equality Issues in Wales: a Research Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

People, Places and Policy

People, Places and Policy Set within the context of UK devolution and constitutional change, People, Places and Policy offers important and interesting insights into ‘place-making’ and ‘locality-making’ in contemporary Wales. Combining policy research with policy-maker and stakeholder interviews at various spatial scales (local, regional, national), it examines the historical processes and working practices that have produced the complex political geography of Wales. This book looks at the economic, social and political geographies of Wales, which in the context of devolution and public service governance are hotly debated. It offers a novel ‘new localities’ theoretical framework for capturing the dynamics of locality-making, to go beyond the obsession with boundaries and coterminous geog- raphies expressed by policy-makers and politicians. Three localities – Heads of the Valleys (north of Cardiff), central and west coast regions (Ceredigion, Pembrokeshire and the former district of Montgomeryshire in Powys) and the A55 corridor (from Wrexham to Holyhead) – are discussed in detail to illustrate this and also reveal the geographical tensions of devolution in contemporary Wales. This book is an original statement on the making of contemporary Wales from the Wales Institute of Social and Economic Research, Data and Methods (WISERD) researchers. It deploys a novel ‘new localities’ theoretical framework and innovative mapping techniques to represent spatial patterns in data. This allows the timely uncovering of both unbounded and fuzzy relational policy geographies, and the more bounded administrative concerns, which come together to produce and reproduce over time Wales’ regional geography. The Open Access version of this book, available at www.tandfebooks.com, has been made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives 3.0 license. -

The Past and the Future of Law in Wales

The Past and the Future of Law in Wales Lord Thomas of Cwmgiedd 27 October 2017, Pierhead Building, Cardiff Wales Governance Centre at Cardiff University Law Building Museum Avenue Cardiff CF10 3AX Email: [email protected] Web: http://sites.cardiff.ac.uk/wgc About us The Wales Governance Centre is a research centre that forms part of Cardiff University’s School of Law and Politics undertaking innovative research into all aspects of the law, politics, government and political economy of Wales, as well the wider UK and European contexts of territorial governance. A key objective of the Centre is to facilitate and encourage informed public debate of key developments in Welsh governance not only through its research, but also through events and postgraduate teaching. Public Law Wales aims to promote discussion, education and research in Wales relating to public law and human rights. It also aims to promote expertise amongst lawyers practising in Wales in the fields of public law and human rights. LORD THOMAS OF CWMGEIDD After reading law at Cambridge and the University of Chicago, Lord Thomas of Cwmgiedd was a practising barrister in England and Wales specialising in commercial law (1971-1996), a Judge of the High Court and Court of Appeal of England and Wales (1996-2011) during which he was successively a Presiding Judge in Wales, Judge in charge of the Commercial Court, Senior Presiding Judge of England and Wales and deputy Head of Criminal Justice. He was President of the Queen’s Bench Division (2011-13) and Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales (2013- 2017). -

Woodlands for Wales Indicators 2014-15

Woodlands for Wales Indicators 2014-15 SDR: 204/2015 Woodlands for Wales Indicators 2014 -15 16 December 2015 This is the sixth indicators report since the revision in March 2009 of Woodlands for Wales, the Welsh Government’s strategy for woodlands and trees. The aim of the indicators is to monitor progress towards achieving the 20 high level outcomes described in Woodlands for Wales. Many of the indicators relate to more than one of the high level outcomes. As some aspects of woodlands and trees change slowly, some indicators are not updated every year, but instead every two, three, or five years, in line with the reporting programme of the National Forest Inventory and some Natural Resources Wales surveys. Some information is only available for limited periods or areas, while for some indicators there is only a baseline figure at present. A few of the indicators are still under development and reporting against these should occur in future years. For more information on the quality of the statistics and the definitions used please refer to the ‘Key Quality Information’ and ‘Glossary’ sections towards the end of the bulletin. Key points The area of woodland in Wales has increased over the last thirteen years and is now 306,000 hectares. The amount of new planting increased between 2009 and 2014 when a total of 3,289 hectares were planted, but the rate of planting fell back in 2015 to 103 hectares. The forestry sector in Wales has an annual Gross Value Added (GVA) of £499.3 million and employs between 8,500 and 11,300 people. -

The Future Development of Transport for Wales

National Assembly for Wales Economy, Infrastructure and Skills Committee The Future Development of Transport for Wales May 2019 www.assembly.wales The National Assembly for Wales is the democratically elected body that represents the interests of Wales and its people, makes laws for Wales, agrees Welsh taxes and holds the Welsh Government to account. An electronic copy of this document can be found on the National Assembly website: www.assembly.wales/SeneddEIS Copies of this document can also be obtained in accessible formats including Braille, large print, audio or hard copy from: Economy, Infrastructure and Skills Committee National Assembly for Wales Cardiff Bay CF99 1NA Tel: 0300 200 6565 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @SeneddEIS © National Assembly for Wales Commission Copyright 2019 The text of this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading or derogatory context. The material must be acknowledged as copyright of the National Assembly for Wales Commission and the title of the document specified. National Assembly for Wales Economy, Infrastructure and Skills Committee The Future Development of Transport for Wales May 2019 www.assembly.wales About the Committee The Committee was established on 28 June 2016. Its remit can be found at: www.assembly.wales/SeneddEIS Committee Chair: Russell George AM Welsh Conservatives Montgomeryshire Current Committee membership: Hefin David AM Vikki Howells AM Welsh Labour Welsh Labour Caerphilly Cynon Valley Mark Reckless AM David J Rowlands AM Welsh Conservative Group UKIP Wales South Wales East South Wales East Jack Sargeant AM Bethan Sayed AM Welsh Labour Plaid Cymru Alyn and Deeside South Wales West Joyce Watson AM Welsh Labour Mid and West Wales The Future Development of Transport for Wales Contents Chair’s foreword ..................................................................................................... -

Hydrogeology of Wales

Hydrogeology of Wales N S Robins and J Davies Contributors D A Jones, Natural Resources Wales and G Farr, British Geological Survey This report was compiled from articles published in Earthwise on 11 February 2016 http://earthwise.bgs.ac.uk/index.php/Category:Hydrogeology_of_Wales BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data © Crown Copyright and database rights 2015. Hydrogeology of Wales Ordnance Survey Licence No. 100021290 EUL. N S Robins and J Davies Bibliographical reference Contributors ROBINS N S, DAVIES, J. 2015. D A Jones, Natural Rsources Wales and Hydrogeology of Wales. British G Farr, British Geological Survey Geological Survey Copyright in materials derived from the British Geological Survey’s work is owned by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and/or the authority that commissioned the work. You may not copy or adapt this publication without first obtaining permission. Contact the BGS Intellectual Property Rights Section, British Geological Survey, Keyworth, e-mail [email protected]. You may quote extracts of a reasonable length without prior permission, provided a full acknowledgement is given of the source of the extract. Maps and diagrams in this book use topography based on Ordnance Survey mapping. Cover photo: Llandberis Slate Quarry, P802416 © NERC 2015. All rights reserved KEYWORTH, NOTTINGHAM BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY 2015 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of our publications is available from BGS British Geological Survey offices shops at Nottingham, Edinburgh, London and Cardiff (Welsh publications only) see contact details below or BGS Central Enquiries Desk shop online at www.geologyshop.com Tel 0115 936 3143 Fax 0115 936 3276 email [email protected] The London Information Office also maintains a reference collection of BGS publications, including Environmental Science Centre, Keyworth, maps, for consultation. -

Evidence from Minister for Economy, Transport And

Memorandum on the Economy and Transport Draft Budget Proposals for 2021-22 Economy, Infrastructure and Skills Committee – 20 January 2021 1.0 Introduction This paper provides information on the Economy & Transport (E&T) budget proposals as outlined in the 2021-22 Draft Budget published on 21 December 2020. It also provides an update on specific areas of interest to the Committee. 2.0 Strategic Context / Covid Impacts Aligned to Prosperity for All and the Well Being and Future Generations Act, the Economic Action Plan is the guiding policy and strategy document for all of Welsh Government’s activities. The 2021-22 plan builds on the considerable progress in implementing and embedding key elements of the plan, involving engagement with a range of stakeholders, particularly the business community and social partners. The pathway to Welsh economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic builds on the foundations of Prosperity for All: The Economic Action Plan. This shaped an economic development programme which invests in people and businesses - driving prosperity and reducing inequality across all of Wales. The mission builds on the early progress we have made in raising the profile and challenges in the Foundational Economy, recognising there is more to be done to spread and scale the approach. Other key initiatives, including Prosperity for All: A Low Carbon Wales, Cymraeg 2050, the Employability Delivery Plan and our Fair Work agenda, run through all interventions. The Well-being of Future Generations Act and its wider framework continue to provide a uniquely Welsh way of tackling the long-term challenges that our people and our planet face. -

Integrating Sustainable Development and Children's Rights

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Article Integrating Sustainable Development and Children’s Rights: A Case Study on Wales Rhian Croke 1,*, Helen Dale 2 , Ally Dunhill 3, Arwyn Roberts 2 , Malvika Unnithan 4 and Jane Williams 5 1 Hillary Rodham Clinton School of Law, Swansea University, Swansea SA2 8PP, UK 2 Lleisiau Bach/Little Voices, National Lottery People and Places Fund 2012-2020, Swansea and Bangor University, Swansea SA2 8PP, UK; [email protected] (H.D.); [email protected] (A.R.) 3 Independent Consultant and Researcher, Kingston Upon Hull HU6 8TA, UK; [email protected] 4 Northumbria University Law School, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 8ST, UK; [email protected] 5 Observatory on the Human Rights of Children, Swansea University, Swansea SA2 8PP, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] Abstract: The global disconnect between the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Conven- tion on the Rights of the Child (CRC), has been described as ‘a missed opportunity’. Since devolution, the Welsh Government has actively pursued a ‘sustainable development’ and a ‘children’s rights’ agenda. However, until recently, these separate agendas also did not contribute to each other, al- though they culminated in two radical and innovative pieces of legislation; the Rights of Children and Young Persons (Wales) Measure (2013) and the Well-being and Future Generations (Wales) Act (2015). This article offers a case study that draws upon the SDGs and the CRC and considers how recent Citation: Croke, Rhian, Helen Dale, Ally Dunhill, Arwyn Roberts, guidance to Welsh public bodies for implementation attempts to contribute to a more integrated Malvika Unnithan, and Jane Williams. -

Llwybr Newydd a New Wales Transport Strategy

Llwybr Newydd The Wales Transport Strategy 2021 Contents From the Ministers 3 5. Holding ourselves and our partners to account 47 Introduction 5 5.1 Transport performance 1. Vision 11 board 48 5.2 A new evaluation 2. Our priorities 13 framework 48 3. Well-being ambitions 22 5.3 Modal shift 48 Good for people and 5.4 Well-being measures 49 communities 23 5.5 Data on modes and sectors 50 Good for the environment 27 6. The five ways of Good for the economy working 48 and places in Wales 31 6.1 Involvement 52 Good for culture and the Welsh language 34 6.2 Collaboration 52 6.3 Prevention 52 4. How we will deliver 38 6.4 Integration 52 4.1 Investing responsibly 40 6.5 Long-term 52 4.2 Delivery and action plans 41 4.3 Cross-cutting delivery 7. Mini-plans 53 pathways 42 7.1 Active travel 56 4.4 Working in partnership 45 7.2 Bus 60 4.5 Updating our policies 7.3 Rail 64 and governance 46 7.4 Roads, streets and parking 68 4.6 Skills and capacity 46 7.5 Third sector 72 7.6 Taxis and private hire vehicles (PHV) 76 7.7 Freight and logistics 80 7.8 Ports and maritime 84 7.9 Aviation 88 Llwybr Newydd - The Wales Transport Strategy 2021 2 But we won’t achieve that level of physical and digital connectivity change unless we take people with to support access to more local Croeso us, listening to users and involving services, more home and remote from the Ministers people in designing a transport working. -

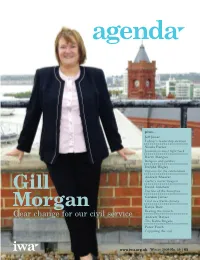

Gill Morgan, Is Dealing with Whitehall Arrogance

plus… Jeff Jones Labour’s leadership election Nicola Porter Journalism must fight back Barry Morgan Religion and politics Dafydd Wigley Options for the referendum Andrew Shearer Garlic’s secret weapon Gill David Culshaw Decline of the honeybee Gordon James Coal in a warm climate Morgan Katija Dew Beating the crunch Gear change for our civil service Andrew Davies The Kafka Brigade Peter Finch Capturing the soul www.iwa.org.uk Winter 2009 No. 39 | £5 clickonwales ! Coming soon, our new website www. iwa.or g.u k, containing much more up-to-date news and information and with a freshly designed new look. Featuring clickonwales – the IWA’s new online service providing news and analysis about current affairs as it affects our small country. Expert contributors from across the political spectrum will be commissioned daily to provide insights into the unfolding drama of the new 21 st Century Wales – whether it be Labour’s leadership election, constitutional change, the climate change debate, arguments about education, or the ongoing problems, successes and shortcomings of the Welsh economy. There will be more scope, too, for interactive debate, and a special section for IWA members. Plus: Information about the IWA’s branches, events, and publications. This will be the must see and must use Welsh website. clickonwales and see where it takes you. clickonwales and see how far you go. The Institute of Welsh Affairs gratefully acknowledges core funding from the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust , the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation and the Waterloo Foundation . The following organisations are corporate members: Private Sector • Principality Building Society • The Electoral Commission Certified Accountants • Abaca Ltd • Royal Hotel Cardiff • Embassy of Ireland • Autism Cymru • Beaufort Research • Royal Mail Group Wales • Fforwm • Cartrefi Cymunedol / • Biffa Waste Services Ltd • RWE NPower Renewables • The Forestry Commission Community Housing Cymru • British Gas • S. -

The Four Health Systems of the United Kingdom: How Do They Compare?

The four health systems of the United Kingdom: how do they compare? Gwyn Bevan, Marina Karanikolos, Jo Exley, Ellen Nolte, Sheelah Connolly and Nicholas Mays Source report April 2014 About this research This report is the fourth in a series dating back to 1999 which looks at how the publicly financed health care systems in the four countries of the UK have fared before and after devolution. The report was commissioned jointly by The Health Foundation and the Nuffield Trust. The research team was led by Nicholas Mays at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. The research looks at how the four national health systems compare and how they have performed in terms of quality and productivity before and after devolution. The research also examines performance in North East England, which is acknowledged to be the region that is most comparable to Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland in terms of socioeconomic and other indicators. This report, along with an accompanying summary report, data appendices, digital outputs and a short report on the history of devolution (to be published later in 2014), are available to download free of charge at www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/compare-uk-health www.health.org.uk/compareUKhealth. Acknowledgements We are grateful: to government statisticians in the four countries for guidance on sources of data, highlighting problems of comparability and for checking the data we have used; for comments on the draft report from anonymous referees and from Vernon Bogdanor, Alec Morton and Laura Schang; and for guidance on national clinical audits from Nick Black and on nursing data from Jim Buchan. -

A Learning Insight Into Demography

A LEARNING INSIGHT INTO DEMOGRAPHY prepared by BMG Research for A Learning Insight into Demography Table of Contents 1. Summary and discussion ................................................................. 1 Introduction........................................................................................ 1 What is ‘demography’........................................................................ 1 Total population change ................................................................... 3 Change in the age structure of the population ............................... 3 Population distribution within Wales............................................... 7 Ethnic minorities in Wales ................................................................ 8 Wealth, poverty and social class...................................................... 9 Gender .............................................................................................. 12 Summary........................................................................................... 13 2. Technical report: introduction....................................................... 15 Scope of report ................................................................................ 15 Sources and references .................................................................. 16 Structure of report ........................................................................... 16 3. Total population and age structure................................................ 17 Introduction..................................................................................... -

WELSH GOVERNMENT - BERNARD GALTON, DIRECTOR GENERAL, PEOPLE, PLACES & CORPORATE SERVICES Business Expenses: April – June 2011

WELSH GOVERNMENT - BERNARD GALTON, DIRECTOR GENERAL, PEOPLE, PLACES & CORPORATE SERVICES Business Expenses: April – June 2011 DATES DESTINATION PURPOSE TRAVEL OTHER (Including Total Cost Hospitality Given) £ Air Rail Taxi / Hire Car/Own Accommodation / car Meals 11/5/11- London Attend various meetings £126.00 £319.98 £445.98 13/5/11 at Cabinet Office 24/5/11- London Attend various meetings £63.00 £169.00 £232.00 25/5/11 26/5/11 London Attend HR Management £114.10 £114.10 Team at Cabinet Office 21/6/11 London Attend HR Management £164.50 £164.50 Team 27/6/11 Lampeter Open Summer School £81.00 £81.00 TOTAL £1,037.58 Hospitality DATE INVITEE/COMPANY EVENT/GIFT COST 24/5/11 Odgers Berndtson Annual HR Directors’ Dinner £40 TOTAL £40 WELSH GOVERNMENT – Clive Bates, Director General, Sustainable Futures Business Expenses: April – June 2011 DATES DESTINATION PURPOSE TRAVEL OTHER (Including Total Hospitality Given) Cost £ Air Rail Taxi / Car Accommodation / Meals 13.4.11 Gwesty Cymru Hotel, Overnight stay at hotel £104.45 £104.45 Aberystwyth for staff visit on 14 April 13- Travel from Home to Travel expenses in own £99.45 £99.45 14.4.11 Hotel Gwesty for car for visit to overnight stay, then Aberystwyth onto Aberystwyth offices and onto home address. 26.4.11 Return train travel from Visit with Newport £4.20 £4.20 Cardiff to Newport Unlimited 12.5.11 Train ticket between To attend Top 200 event £28.50 + £60.50 Cardiff and London £32.00 19.5.11 Train ticket Cardiff – To attend Climate £4.00 £4.00 Barry Docks return Change & Energy- Member Development & Training for Vale of Glamorgan Council 27.5.11 Return train travel to to attend CBI dinner £7.30 £7.30 Swansea on 7 June (speaking at event) 27.5.11 Return train travel to to attend Climate £66.00 + £88.00 for London Change Forum Private £22.00 travel Dinner on 8.6.11 27.6.11 Wolfscastle Country Intended Overnight stay £78.00 £78.00 Hotel, to attend CCW Annual Wolfscastle, meeting & Dinner, Haverfordwest however cancelled on Pembrokeshire.