Shenmue Sacred Spot Guide Map

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT 2000 SEGA CORPORATION Year Ended March 31, 2000 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS SEGA Enterprises, Ltd

ANNUAL REPORT 2000 SEGA CORPORATION Year ended March 31, 2000 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS SEGA Enterprises, Ltd. and Consolidated Subsidiaries Years ended March 31, 1998, 1999 and 2000 Thousands of Millions of yen U.S. dollars 1998 1999 2000 2000 For the year: Net sales: Consumer products ........................................................................................................ ¥114,457 ¥084,694 ¥186,189 $1,754,018 Amusement center operations ...................................................................................... 94,521 93,128 79,212 746,227 Amusement machine sales............................................................................................ 122,627 88,372 73,654 693,867 Total ........................................................................................................................... ¥331,605 ¥266,194 ¥339,055 $3,194,112 Cost of sales ...................................................................................................................... ¥270,710 ¥201,819 ¥290,492 $2,736,618 Gross profit ........................................................................................................................ 60,895 64,375 48,563 457,494 Selling, general and administrative expenses .................................................................. 74,862 62,287 88,917 837,654 Operating (loss) income ..................................................................................................... (13,967) 2,088 (40,354) (380,160) Net loss............................................................................................................................. -

Title ODATE GAME

Title ODATE GAME : character design and modelling for Japanese modesty culture based independent video game Sub Title Author 鄒、琰(Zou, Yan) 太田, 直久(Ota, Naohisa) Publisher 慶應義塾大学大学院メディアデザイン研究科 Publication year 2014 Jtitle Abstract Notes 修士学位論文. 2014年度メディアデザイン学 第395号 Genre Thesis or Dissertation URL https://koara.lib.keio.ac.jp/xoonips/modules/xoonips/detail.php?koara_id=KO40001001-0000201 4-0395 慶應義塾大学学術情報リポジトリ(KOARA)に掲載されているコンテンツの著作権は、それぞれの著作者、学会または出版社/発行者に帰属し、その権利は著作権法によって 保護されています。引用にあたっては、著作権法を遵守してご利用ください。 The copyrights of content available on the KeiO Associated Repository of Academic resources (KOARA) belong to the respective authors, academic societies, or publishers/issuers, and these rights are protected by the Japanese Copyright Act. When quoting the content, please follow the Japanese copyright act. Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Master's Thesis Academic Year 2014 ODATE GAME: Character Design and Modelling for Japanese Modesty Culture Based Independent Video Game Graduate School of Media Design, Keio University Yan Zou A Master's Thesis submitted to Graduate School of Media Design, Keio University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER of Media Design Yan Zou Thesis Committee: Professor Naohisa Ohta (Supervisor) Associate Professor Kazunori Sugiura (Co-Supervisor) Associate Professor Nanako Ishido (Co-Supervisor) Abstract of Master's Thesis of Academic Year 2014 ODATE GAME: Character Design and Modelling for Japanese Modesty Culture Based Independent Video Game Category: Design Summary Game character design is an important part of game design. Game characters cannot be designed only according to the designer's experience or the players' preferences. They should be strongly associated to the game system and also the story. A good game character design is not only the reason for players to purchase the game but it also can improve players' entire game experience. -

How World of Warships Doubled Referrals with Amazon Moments

How World of Warships doubled referrals with Amazon Moments 100% 38% 20% 42% increase in increase in average increase in conversions decrease in cost referrals revenue per user to payers per action CHALLENGES World of Warships is a free-to-play naval warfare-themed multiplayer online game produced and published by Wargaming. World of Warships had an existing referral program targeted at both acquiring new players and winning back lapsed players (over 90 days inactive) but wanted to improve the participation numbers and make it more valuable for players to refer their friends. In addition, they were looking to explore the potential of a rewards powered referral program as a more cost effective user acquisition channel. World of Warships had previously tested a small pilot campaign to enable rewards for referrals but needed a more streamlined solution for providing rewards across multiple countries. Amazon Moments allowed World of Warships to easily deliver valuable, real-world rewards to players to drive acquisition and winback and lower acquisition costs. SOLUTION To increase player referrals and drive stickiness for new and returning users, World of Warships launched a Moments-powered campaign that provided Amazon credits to players who referred a friend (a recruit). Recruits were invited to join or return to the game via personal referral links sent by World of Warships players. To qualify for the referral reward, new recruits needed to play a battle on a non-premium tier 6 ship, and returned players needed to win 25 battles. To participate in the referral program, players needed to have at least 15 battles played on their account. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

Shenmue Gamespot Guide

GameSpot Game Guide: Shenmue ã Copyright 2000 GameSpot, a division of ZD Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part in any form or in any medium without express permission of GameSpot is prohibited. GameSpot, videogames.com, VideoGameSpot are trademarks or registered trademarks of ZDNet Inc. This wholly independent product is the sole property of GameSpot. It is neither authorized or sponsored by, nor licensed or affiliated with Sega of America Inc. Shenmue and its characters are trademarks of Sega of America Inc. All titles, items, characters, and products described or referred to in this guide are trademarks of their respective companies. 2 GameSpot Game Guide: Shenmue Guide Contents Introduction 4 Chapter 1: General Strategies 5 How to Dive In 5 Quick Timer Events 5 Free Battles 6 Being Optional Can Be Fun 9 Chapter 2: Disc One Walk-Through 11 Hazuki Residence 11 Yamanose 14 Sakuragaoka 15 Dobuita 16 Chapter 3: Disc Two Walk-Through 31 New Yokosuka Harbor 31 Hazuki Residence 36 Trip to Hong Kong 43 Chapter 4: Disc Three Walk-Through 48 Getting a Job at the Harbor 49 First Day on the Job 53 Second Day on the Job 55 Third Day on the Job 57 Fourth Day on the Job 58 Fifth Day on the Job 60 Rescuing Nozomi 61 70-Man Battle 63 Final Battle with Chai 65 3 GameSpot Game Guide: Shenmue Introduction n late November 1986, Ryo Hazuki came home and witnessed his father's death at the hands of an ominous man named Lan Di. You assume the role Iof Ryo Hazuki on his quest to uncover the truth behind his father's death and to understand the meaning behind the mysterious mirror that Lan Di so desperately seeks. -

From the Director's Chair

Newsletter of the Battleship Texas Foundation Spring 2018 In this issue . From The Director's Chair The Director's Chair Pg1 I wanted to share with you the highly successful partnership we have done with Wargaming.net. FTV Report Pg3 Battleship Texas Foundation Announces Partnership with OEP Report Pg4 Wargaming to Preserve Battleship TEXAS, Project VALOR Curators Corner Pg5 HOUSTON (Jan. XX, 2018) – Battleship Texas Foundation has announced its joint partnership with Wargaming.net, a Supporters Pg6 leading online game developer and publisher, to preserve In Memory Of Pg7 the historic naval ship, Battleship TEXAS. The Foundation and Wargaming collaborated to create World of Warships, a Membership Forms Pg8 free, online historical combat game, that allows participants to command ships from massive naval fleets with history’s most iconic vessels. World of Warships is part of the Project VALOR (Veterans and Loved Ones Responsibility) campaign, Wargaming’s Navy Poster . four-part charity program emphasizing family, home, remembrance and giving thanks. To date, the campaign has raised more than $281,000 from World of Warships’ players. All proceeds garnered will support the restoration of Battleship TEXAS. A 34-year veteran and hallmark of honor and strength, the Battleship TEXAS served the United States in both World War I and World War II. Commissioned in 1914 as the most powerful weapon in the world, she is credited with the introduction and innovation of advances in gunnery, aviation and radar. She is the last surviving dreadnought and the only battleship in existence today that fought in both world wars. continued on next page Battleship TEXAS Foundation From The Director's Chair continued Advisory Directors Hon. -

Global Pop Cultures. Moving Beyond the High–Low, East–West Divide Conference and Workshop Organized by Kyoto Seika University and Zurich University of the Arts (Zhdk)

Global Pop Cultures. Moving Beyond the High–Low, East–West Divide Conference and Workshop Organized by Kyoto Seika University and Zurich University of the Arts (ZHdK) Hosted by Kyoto Seika University Shared Campus July 29 — 31, 2019 Global Pop Cultures sities from Europe and Asia (see below). We consider Pop culture is one of the most salient driving forces in close cooperation as imperative to tackle issues of glob- the globalization and innovation of cultures. Pop is also al significance. We are convinced that especially the arts a sphere where politics, identities, and social questions can, and indeed ought to, play an important role in this are negotiated. Rather than denoting only the culture respect. Shared Campus endeavours to create connec- for and of the masses, pop is characterized by the dia- tions that bring value to students, faculty and research- lectical interplay between mainstream and subculture, ers by developing and offering joint transnational educa- their respective milieus and markets. Today, the theory tion and research activities. These collaborative ventures and practice of pop is thoroughly globalized and will enable participants to share knowledge and compe- hybrid. Pop exists only in plural. Global pop cultures are tences across cultural and disciplinary boundaries. characterized by a high degree of variability, plasticity, The platform is designed around thematic clusters of and connectivity. A further reason for the growing com- international relevance with a distinctive focus on trans- plexity of global pop cultures is the fact that pop is no cultural issues and cross-disciplinary collaboration. longer only a DIY culture of amateurs. -

Free Pc Game Downloads' PC Games Free Download Full Version for Windows 10 Offline

free pc game downloads' PC Games Free Download Full Version For Windows 10 Offline. The list below contains different games that can suit a variety of players and their hobbies. Popular genres like racing games, shooters, or simulators can be all found at ease, and totally available for a full download to any Windows 10 device! On the hunt for some of the best PC games that can be downloaded and installed free, we have conducted tons of 'researches' to eventually write down such a list in this article. The list below contains different genres that can suit a variety of players and their hobbies. Popular genres like racing games, puzzles, games for children, or simulators can be all found at ease, and totally available for a full download to any devices that run Windows 10. Don't hesitate to try out the following PC games free download full version for Windows 10 offline if you don't know how to deal with your spare time! Table of Contents. Minecraft: Story Mode - A Telltale Games Series. There is not much to suspect about the popularity of Minecraft, especially its Story Mode version that is built thanks to the original one with several changes in terms of story. In total, there are eight episodes but only some of which can be purchased free. After the characters are introduced, the story will begin. Minecraft: Story Mode - A Telltale Games Series. The content will not be disclosed in this article but it will be absolutely amazing to explore. It appears to be made for the children only, but humorous features in the game will surely make everyone, from the aged to the young, relax after long hours of working. -

MEDIA CONTACT: Aram Jabbari Atlus U.S.A., Inc

MEDIA CONTACT: Aram Jabbari Atlus U.S.A., Inc. FOR IMMEDIATE 949-788-0455 (x102) RELEASE [email protected] ATLUS U.S.A., INC. ANNOUNCES SHIN MEGAMI TENSEI®: PERSONA 3™ WEBSITE LAUNCH! Locked away in the human psyche is power beyond imagination... IRVINE, CALIFORNIA — JULY 10th, 2007 — Atlus U.S.A., Inc., a leading publisher of interactive entertainment, today announced the launch of the official website for Shin Megami Tensei: Persona 3! Enormously successful in Japan, P3 is the newest RPG from the publisher of the acclaimed Shin Megami Tensei series. After eight long years of anticipation, fans have very little left to wait. Shin Megami Tensei: Persona 3 is set to ship on July 24, 2007, exclusively for the PlayStation®2 computer entertainment system. Every copy is a deluxe edition with a 52-page color art book and soundtrack CD! Shin Megami Tensei: Persona 3 has been rated “M” for Mature by the ESRB for Blood, Language, Partial Nudity, and Violence. About Shin Megami Tensei: Persona 3: In Persona 3, you’ll assume the role of a high school student, orphaned as a young boy, who’s recently transferred to Gekkoukan High School on Port Island. Shortly after his arrival, he is attacked by creatures of the night known as Shadows. The assault awakens his Persona, Orpheus, from the depths of his subconscious, enabling him to defeat the terrifying foes. He soon discovers that he shares this special ability with other students at his new school. From them, he learns of the Dark Hour, a hidden time that exists between one day and the next, swarming with Shadows. -

AN 362 JAPANESE POPULAR CULTURE IES Abroad Tokyo

AN 362 JAPANESE POPULAR CULTURE IES Abroad Tokyo DESCRIPTION: This course examines contemporary Japanese popular culture from historical, social, and anthropological perspectives. The course will examine very recent topics in an attempt to understand Japanese culture as it exists today. The scope of topics examined will be wide ranging, including folklore, anime, manga, advertising, cinema, music, food and politics. As this last year was the 70th anniversary of the end of the end of World War II and an important year of reflection in Japan, special emphasis will be given to war memory, militarism, and pacifism in Japan’s postwar popular culture. The objective of this course is to provide students with an academic understanding of Japanese popular culture & mass culture through the study of scholarly perspectives from the fields of anthropology, sociology, and media studies. CREDITS: 3 CONTACT HOURS: 45 LANGUAGE OF PRESENTATION: English PREREQUSITES: None METHOD OF PRESENTATION: Class sessions will consist of active group discussions and student presentations. Assignments for the course consist of weekly responses to each week’s class, short response papers about class field trips, a final paper, and a final presentation. REQUIRED WORK AND FORM OF ASSESSMENT: • Class Participation – 25% • Presentation (Mid-term Exam) - 20% • Weekly Responses - 25% • Research Paper & Presentation (Final Exam) - 30% Course Participation Students are expected to attend all class meetings. The first and most important assignment is to read and reflect on the readings and come to class prepared to talk about them. One missed class turns an A into an A-, two missed classes turns it into a B-, three turns it into a C-, and so on. -

Video Game Trader Magazine & Price Guide

Winter 2009/2010 Issue #14 4 Trading Thoughts 20 Hidden Gems Blue‘s Journey (Neo Geo) Video Game Flashback Dragon‘s Lair (NES) Hidden Gems 8 NES Archives p. 20 19 Page Turners Wrecking Crew Vintage Games 9 Retro Reviews 40 Made in Japan Coin-Op.TV Volume 2 (DVD) Twinkle Star Sprites Alf (Sega Master System) VectrexMad! AutoFire Dongle (Vectrex) 41 Video Game Programming ROM Hacking Part 2 11Homebrew Reviews Ultimate Frogger Championship (NES) 42 Six Feet Under Phantasm (Atari 2600) Accessories Mad Bodies (Atari Jaguar) 44 Just 4 Qix Qix 46 Press Start Comic Michael Thomasson’s Just 4 Qix 5 Bubsy: What Could Possibly Go Wrong? p. 44 6 Spike: Alive and Well in the land of Vectors 14 Special Book Preview: Classic Home Video Games (1985-1988) 43 Token Appreciation Altered Beast 22 Prices for popular consoles from the Atari 2600 Six Feet Under to Sony PlayStation. Now includes 3DO & Complete p. 42 Game Lists! Advertise with Video Game Trader! Multiple run discounts of up to 25% apply THIS ISSUES CONTRIBUTORS: when you run your ad for consecutive Dustin Gulley Brett Weiss Ad Deadlines are 12 Noon Eastern months. Email for full details or visit our ad- Jim Combs Pat “Coldguy” December 1, 2009 (for Issue #15 Spring vertising page on videogametrader.com. Kevin H Gerard Buchko 2010) Agents J & K Dick Ward February 1, 2009(for Issue #16 Summer Video Game Trader can help create your ad- Michael Thomasson John Hancock 2010) vertisement. Email us with your requirements for a price quote. P. Ian Nicholson Peter G NEW!! Low, Full Color, Advertising Rates! -

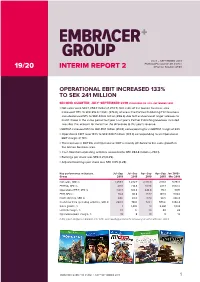

19/20 Interim Report 2 Reg No

JULY – SEPTEMBER 2019 EMBRACER GROUP AB (PUBL) 19/20 INTERIM REPORT 2 REG NO. 556582-6558 OPERATIONAL EBIT INCREASED 133% TO SEK 241 MILLION SECOND QUARTER, JULY–SEPTEMBER 2019 (COMPARED TO JULY–SEPTEMBER 2018) > Net sales were SEK 1,259.7 million (1,272.7). Net sales of the Games business area increased 117% to SEK 816.0 million (376.0), whereas the Partner Publishing/Film business area decreased 51% to SEK 443.6 million (896.6) due to the absence of larger releases to match those in the same period last year. Last year’s Partner Publishing revenues included two titles that account for more than the difference to this year’s revenue. > EBITDA increased 95% to SEK 418.1 million (214.8), corresponding to an EBITDA margin of 33%. > Operational EBIT rose 133% to SEK 240.7 million (103.4) corresponding to an Operational EBIT margin of 19%. > The increase in EBITDA and Operational EBIT is mainly attributed to the sales growth in the Games business area. > Cash flow from operating activities amounted to SEK 284.8 million (–740.1). > Earnings per share was SEK 0.21 (0.25). > Adjusted earnings per share was SEK 0.65 (0.28). Key performance indicators, Jul–Sep Jul–Sep Apr–Sep Apr–Sep Jan 2018– Group 2019 2018 2019 2018 Mar 2019 Net sales, SEK m 1,259.7 1,272.7 2,401.8 2,110.1 5,754.1 EBITDA, SEK m 418.1 214.8 807.6 421.7 1,592.6 Operational EBIT, SEK m 240.7 103.4 444.8 173.1 897.1 EBIT, SEK m 76.4 90.8 157.7 143.3 574.6 Profit after tax, SEK m 64.6 65.0 117.4 98.5 396.8 Cash flow from operating activities, SEK m 284.8 –740.1 723.1 –575.6 1,356.4 Sales growth, % –1 1,403 14 2,281 1,034 EBITDA margin, % 33 17 34 20 28 Operational EBIT margin, % 19 8 19 8 16 In this report, all figures in brackets refer to the corresponding period of the previous year, unless otherwise stated.