SOAG Bulletin 44

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thames Valley Papists from Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829

Thames Valley Papists From Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829 Tony Hadland Copyright © 1992 & 2004 by Tony Hadland All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without prior permission in writing from the publisher and author. The moral right of Tony Hadland to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 9547547 0 0 First edition published as a hardback by Tony Hadland in 1992. This new edition published in soft cover in April 2004 by The Mapledurham 1997 Trust, Mapledurham HOUSE, Reading, RG4 7TR. Pre-press and design by Tony Hadland E-mail: [email protected] Printed by Antony Rowe Limited, 2 Whittle Drive, Highfield Industrial Estate, Eastbourne, East Sussex, BN23 6QT. E-mail: [email protected] While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, neither the author nor the publisher can be held responsible for any loss or inconvenience arising from errors contained in this work. Feedback from readers on points of accuracy will be welcomed and should be e-mailed to [email protected] or mailed to the author via the publisher. Front cover: Mapledurham House, front elevation. Back cover: Mapledurham House, as seen from the Thames. A high gable end, clad in reflective oyster shells, indicated a safe house for Catholics. -

Winter Newsletter, January 2019

Winter Newsletter, January 2019 From the Chairman Contents Dear Friends Letter from Chairman 1 The Secretary’s Minute The festivities are over. Winter is here. We are now in the dread days of January. But still Book 3 the Ridgeway is there to refresh and uplift the spirit in the winter cold with the rebirth of History of the Ridgeway 3 spring to look forward to. The Swire Ridgeway Arts Prize 6 The Friends of the Ridgeway were founded some 35 years ago to preserve the spirit of the Ridgeway mainly in response to the abuse of the trail by motorised off-road vehicles. Circular pub walks on the Unfortunately, even though use of motorised vehicles is restricted on much of the trail, Ridgeway 7 reports of damage to the trail and improper use of motor vehicles continue to be received. A recent report concerned increasing 4x4 activities on the stretch of the trail between the A338 Wantage/Great Shefford road and the B road from Wantage/Newbury. Damage was reported by two riders; one horse fell over when her hoof got stuck in a wheel rut on a slope, causing both horse and rider to crash to the ground. The horse was surprisingly unhurt, although very muddy on one side, but the rider sustained a painful shoulder. This accident is believed to be entirely due to traffic use. But unfortunately the actual vehicles damaging that section of the trail have not been seen meaning that no evidence is available to use in any action. In a separate incident, a group of 4x4s were reported driving west along the trail, just to the west of the Sparsholt Firs car park on Sunday morning 20 January 2019. -

Crowmarsh Parish Neighbourhood Plan 2020-2035

CROWMARSH PARISH NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN 2020-2035 Submission version 1 Cover picture: Riverside Meadows Local Green Space (Policy CRP 6) 2 CROWMARSH PARISH NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN 2020-2035 Submission version CONTENTS page 1. Introduction 6 • The Parish Vision • Objectives of the Plan 2. The neighbourhood area 10 3. Planning policy context 21 4. Community views 24 5. Land use planning policies 27 • Policy CRP1: Village boundaries and infill development • Policy CRP2: Housing mix and tenure • Policy CRP3: Land at Howbery Park, Benson Lane, Crowmarsh Gifford • Policy CRP4: Conservation of the environment • Policy CRP5: Protection and enhancement of ecology and biodiversity • Policy CRP6: Green spaces 6. Implementation 42 Crowmarsh Parish Council January 2021 3 List of Figures 1. Designated area of Crowmarsh Parish Neighbourhood Plan 2. Schematic cross-section of groundwater flow system through Crowmarsh Gifford 3. Location of spring line and main springs 4. Environment Agency Flood risk map 5. Chilterns AONB showing also the Ridgeway National Trail 6. Natural England Agricultural Land Classification 7. Listed buildings in and around Crowmarsh Parish 8. Crowmarsh Gifford and the Areas of Natural Outstanding Beauty 9. Policies Map 9A. Inset Map A Crowmarsh Gifford 9B. Insert Map B Mongewell 9C. Insert Map C North Stoke 4 List of Appendices* 1. Baseline Report 2. Environment and Heritage Supporting Evidence 3. Housing Needs Assessment 4. Landscape Survey and Impact Assessment 5. Site Assessment Crowmarsh Gifford 6. Strategic Environment Assessment 7. Consultation Statement 8. Compliance Statement * Issued as a set of eight separate documents to accompany the Plan 5 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Neighbourhood Plans are a recently introduced planning document subsequent to the Localism Act, which came into force in April 2012. -

Pyrton Neighbourhood Plan 2018 – 2033 Final PDF

Pyrton Neighbourhood Plan 2018 – 2033 Final PDF Pyrton Neighbourhood Plan 2018 - 2033 Pyrton Parish Council Planning for the future of the parish V11.0 5th February 2018 Page 1 of 57 Pyrton Neighbourhood Plan 2018 – 2033 Final PDF Contents 1. Foreword 5 2. Executive summary 7 2.1. Background to neighbourhood plans 7 2.2. Preparation of the Pyrton Neighbourhood Plan (PNP) 7 2.3. Sensitive local context 8 2.4. Key factors bearing on the PNP 8 2.5. Proposed sites for development 9 3. Introduction and background 10 3.1. Neighbourhood planning and its purpose 10 3.1.1. What is neighbourhood planning? 10 3.1.2. What is a NP? 10 3.1.3. What can a NP include? 10 3.1.4. Basic conditions for a NP 11 3.1.5. Neighbourhood plan area 11 3.1.6. Reasons for preparing a NP 12 3.1.7. Structure of the plan 13 4. Description of Pyrton Parish 14 4.1. Introduction 14 4.2. Location 14 4.3. Historical context 15 4.4. Demographics 23 4.5. Local services and facilities 23 4.6. Employment 24 4.7. Other notable sites within parish 24 4.8. Planning policy context and applicable designations 26 4.8.1. Policy context 26 4.8.2. Planning and environmental designations 28 5. Purpose of the plan 32 5.1. Introduction 32 5.2. Consultation and data collection 32 5.2.1. What do residents value in Pyrton? 32 5.2.2. How to conserve and enhance the quality of the built and natural environment in Pyrton? 32 5.2.3. -

October 2019 BUS INFORMATION the Following Bus Companies

October 2019 BUS INFORMATION The following bus companies operate buses to Gillotts School. Horseman Coaches 01189 753811 www.horsemancoaches.co.uk M&M Coaches 01494 761926 www.mmcoaches.co.uk Sprinters Travel 01628 200052 www.sprinterstravel.co.uk Whites Coaches (local public bus service) 01865 340516 www.whitescoaches.com Arriva (local public bus service) 0344 8004411 www.arrivabus.co.uk Oxfordshire County Council may provide free transport (or meet the cost of travel) for your child if he or she has to travel more than three miles to school, providing Gillotts School is your nearest available school. This distance is measured as the nearest available safe walking route. They may also provide free transport if your child is eligible for free school meals or you are on a low income. If you think your child may be eligible for this support, please contact Oxfordshire County Council, Quality Management Team 01865 323500 or [email protected] Alternatively, parents may be able to pay for spare seats on school buses operating for students who qualify for statutory transport. More information regarding this can be found on the Oxfordshire County Council website. There are also local public buses that serve Gillotts School. Parents of pupils who live closer to another available school but choose to come to Gillotts should contact the bus company operating the route nearest to their home to make their own arrangements. Transport costs for pupils in these circumstances are the responsibility of parents. The current bus routes are attached but stops and times do vary slightly from year to year depending on demand so it is best to check with the relevant bus companies direct and not rely solely on this information. -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

Neighbourhood Development Plan 2017-2033 Submission Version

Neighbourhood Development Plan 2017-2033 Submission Version ‘Our Community… Our Plan’ Document: Watlington Parish Council WNDP 1 October 2017 Watlington Town Hall Page 2 of 60 WNDP 1 Executive Summary The Watlington Neighbourhood Development Plan (WNDP) has been prepared in order to guide the growth of the town from 2017 to 2033. The aim of the plan is to ensure that the local community continues to thrive as the population increases and that Watlington remains a place where people want to live and work. The town and surrounding settlements are mutually dependent and the sustainability of this relationship is at the heart of the plan. The process of developing the plan has been evidence based, rigorous and objective. It has been genuinely community led with over 50 people actively involved and many more contributing to consultations, meetings, discussions, surveys and workshops. Policies in the WNDP comply with European requirements, national planning policy and guidance and district strategic planning policies while providing a strong local focus. The WNDP has the following aims: • To provide a minimum number of 238 new homes to meet the housing needs identified by the WNDP and the requirements of the emerging SODC Local Plan 2033. • To provide a sufficient number of new homes for Watlington which are in proportion to the capacity, services and facilities of the town. • To provide development which contributes positively to the environmental, social and economic sustainability of whole of the WNDP area. • To protect and enhance the surrounding landscape and the Chilterns Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). • To protect and enhance the historic centre of the town. -

PISHILL with STONOR PARISH COUNCIL Minutes of Annual

Website address: www.pishillwithstonorpc.co.uk PISHILL WITH STONOR PARISH COUNCIL Minutes of Annual Meeting held at The Quince Tree, Almshill Room, Stonor, on Thursday, 2 nd May 2013 Present Mr. T. Dunn Chairman Mr. S.Stracey Vice-Chairman Mr. P.G.Godfrey Mr. R. Hunt Mrs. P. Pearce Parish Clerk Also present: Oxfordshire County Councillor Mrs. C. Newton, South Oxfordshire District Councillor Revd. Angie Paterson. 5 parishioners: Mr.S. Haq, Mr.M. Hoare, Mr. and Mrs. D. Reed, Mrs. A. Taylor. The meeting was opened by Mr.T. Dunn who welcomed all those attending. 1. Apologies for absence Mrs.D. Newell (unwell). 2. Parish Report by the Chairman, Mr.T. Dunn Planning There were 13 planning applications from January 2012 to January 2013. The Parish Council approved 11, refused none, gave no strong views for 2. SODC approved all 13. H.M. The Queen’s Diamond Jubilee A Celebration Barbecue was held in appalling weather at White Pond Farm on Sunday 3 rd June, 2012. The tickets sold covered all food, drinks and tractor rides and 174 people came to the barbecue. Mr.Julian Blumfield had kindly designed and produced all the invitations. The Quince Tree generously donated a celebratory cake, which was cut by Mrs.Edith Stanmore of Stonor, who is the parish’s most senior resident. Many parishioners donated salads, puddings and other items, all of which were very gratefully received and helped to keep the costs to a minimum. Pishill Church generously gave each child living in the Parish a commemorative mug, sourced by Guy Godfrey, free of charge. -

Rawlinson's Proposed History of Oxfordshire

Rawlinson's Proposed History of Oxfordshire By B. J. ENRIGHT INthe English Topographer, published in 1720, Richard Rawlinson described the manuscript and printed sources from which a history of Oxfordshire might be compiled and declared regretfully, ' of this County .. we have as yet no perfect Description.' He hastened to add in that mysteriously weH informed manner which invariably betokened reference to his own activities: But of this County there has been, for some Years past, a Description under Consideration, and great Materials have been collected, many Plates engraved, an actual Survey taken, and Quaeries publish'd and dispers'd over the County, to shew the Nature of the Design, as well to procure Informations from the Gentry and others, which have, in some measure, answer'd the Design, and encouraged the Undertaker to pursue it with all convenient Speed. In this Work will be included the Antiquities of the Town and City of Oxford, which Mr. Anthony d l-Vood, in Page 28 of his second Volume of Athenae Oxonienses, &c. promised, and has since been faithfully transcribed from his Papers, as well as very much enJarg'd and corrected from antient Original Authorities. I At a time when antiquarian studies were rapidly losing their appeal after the halcyon days of the 17th-century,' this attempt to compile a large-scale history of a county which had received so little attention caUs for investigation. In proposing to publish a history of Oxfordshirc at this time, Rawlinson was being far less unrealistic thall might at first appear. For -

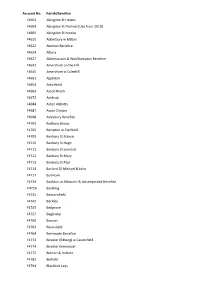

List of Fee Account

Account No. Parish/Benefice F4603 Abingdon St Helens F4604 Abingdon St Michael (Use from 2019) F4605 Abingdon St Nicolas F4610 Adderbury w Milton F4622 Akeman Benefice F4624 Albury F4627 Aldermaston & Woolhampton Benefice F4642 Amersham on the Hill F4645 Amersham w Coleshill F4651 Appleton F4654 Arborfield F4663 Ascot Heath F4672 Ashbury F4684 Aston Abbotts F4687 Aston Clinton F4698 Aylesbury Benefice F4703 Badbury Group F4705 Bampton w Clanfield F4709 Banbury St Francis F4710 Banbury St Hugh F4711 Banbury St Leonard F4712 Banbury St Mary F4713 Banbury St Paul F4714 Barford SS Michael & John F4717 Barkham F4724 Basildon w Aldworth & Ashampstead Benefice F4726 Baulking F4735 Beaconsfield F4742 Beckley F4745 Bedgrove F4757 Begbroke F4760 Benson F4763 Berinsfield F4764 Bernwode Benefice F4773 Bicester (Edburg) w Caversfield F4774 Bicester Emmanuel F4775 Bierton & Hulcott F4782 Binfield F4794 Blackbird Leys F4797 Bladon F4803 Bledlow w Saunderton & Horsenden F4809 Bletchley F4815 Bloxham Benefice F4821 Bodicote F4836 Bracknell Team Ministry F4843 Bradfield & Stanford Dingley F4845 Bray w Braywood F6479 Britwell F4866 Brize Norton F4872 Broughton F4875 Broughton w North Newington F4881 Buckingham Benefice F4885 Buckland F4888 Bucklebury F4891 Bucknell F4893 Burchetts Green Benefice F4894 Burford Benefice F4897 Burghfield F4900 Burnham F4915 Carterton F4934 Caversham Park F4931 Caversham St Andrew F4928 Caversham Thameside & Mapledurham Benefice F4936 Chalfont St Giles F4939 Chalfont St Peter F4945 Chalgrove w Berrick Salome F4947 Charlbury -

The Complete Sedilia Handlist of England and Wales

Church Best image Sedilia Type Period County Diocese Archdeaconry Value Type of church Dividing element Seats Levels Features Barton-le-Clay NONE Classic Geo Bedfordshire LINCOLN BEDFORD £12 / 0 / 0 Parish 3 2 Bedford, St John the Baptist NONE Classic Dec Bedfordshire LINCOLN BEDFORD Attached shaft 3 1 Cap Framed Fig Biggleswade flickr Derek N Jones Classic Dec Bedfordshire LINCOLN BEDFORD £46 / 13 / 4 Parish, prebend, vicarage Detached shaft 3 3 Cap Blunham flickr cambridge lad1 Classic Dec Bedfordshire LINCOLN BEDFORD £20 / 0 / 0 Parish Detached shaft 3 3 Cap Caddington NONE Classic Geo Bedfordshire LINCOLN BEDFORD £16 / 0 / 0 Parish, prebend, vicarage Framed Clifton church site, c.1820 Classic Dec Bedfordshire LINCOLN BEDFORD £7 / 6 / 8 Parish Detached shaft 2 2 Croc Dunton NONE Classic Dec Bedfordshire NORWICH NORFOLK £10 / 0 / 0 Parish, vicarage, appropriated 3 Plain Higham Gobion NONE Classic Perp Bedfordshire LINCOLN BEDFORD £4 / 13 / 4 Parish 3 Goldington NONE Drop sill Perp Bedfordshire LINCOLN BEDFORD £2 / 13 / 4 Parish, vicarage, appropriated 2 2 Lower Gravenhurst waymarking.com Classic Dec Bedfordshire LINCOLN BEDFORD Detached shaft 2 1 Framed Luton flickr stiffleaf Classic Perp Bedfordshire LINCOLN BEDFORD £66 / 13 / 4 Parish, vicarage, appropriated Attached shaft 4 1 Cap Croc Framed Fig Shields Odell NONE Drop sill Perp Bedfordshire LINCOLN BEDFORD £13 / 6 / 8 Parish 3 3 Sandy church site Classic Perp Bedfordshire LINCOLN BEDFORD £13 / 6 / 8 Parish Detached shaft 3 3 Framed Sharnbrook N chapel NONE Classic Dec Bedfordshire -

Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxford Archdeacons’ Marriage Bond Extracts 1 1634 - 1849 Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1634 Allibone, John Overworton Wheeler, Sarah Overworton 1634 Allowaie,Thomas Mapledurham Holmes, Alice Mapledurham 1634 Barber, John Worcester Weston, Anne Cornwell 1634 Bates, Thomas Monken Hadley, Herts Marten, Anne Witney 1634 Bayleyes, William Kidlington Hutt, Grace Kidlington 1634 Bickerstaffe, Richard Little Rollright Rainbowe, Anne Little Rollright 1634 Bland, William Oxford Simpson, Bridget Oxford 1634 Broome, Thomas Bicester Hawkins, Phillis Bicester 1634 Carter, John Oxford Walter, Margaret Oxford 1634 Chettway, Richard Broughton Gibbons, Alice Broughton 1634 Colliar, John Wootton Benn, Elizabeth Woodstock 1634 Coxe, Luke Chalgrove Winchester, Katherine Stadley 1634 Cooper, William Witney Bayly, Anne Wilcote 1634 Cox, John Goring Gaunte, Anne Weston 1634 Cunningham, William Abbingdon, Berks Blake, Joane Oxford 1634 Curtis, John Reading, Berks Bonner, Elizabeth Oxford 1634 Day, Edward Headington Pymm, Agnes Heddington 1634 Dennatt, Thomas Middleton Stoney Holloway, Susan Eynsham 1634 Dudley, Vincent Whately Ward, Anne Forest Hill 1634 Eaton, William Heythrop Rymmel, Mary Heythrop 1634 Eynde, Richard Headington French, Joane Cowley 1634 Farmer, John Coggs Townsend, Joane Coggs 1634 Fox, Henry Westcot Barton Townsend, Ursula Upper Tise, Warc 1634 Freeman, Wm Spellsbury Harris, Mary Long Hanburowe 1634 Goldsmith, John Middle Barton Izzley, Anne Westcot Barton 1634 Goodall, Richard Kencott Taylor, Alice Kencott 1634 Greenville, Francis Inner