Newnham Murren (May 2017) • © Univ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thames Valley Papists from Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829

Thames Valley Papists From Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829 Tony Hadland Copyright © 1992 & 2004 by Tony Hadland All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without prior permission in writing from the publisher and author. The moral right of Tony Hadland to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 9547547 0 0 First edition published as a hardback by Tony Hadland in 1992. This new edition published in soft cover in April 2004 by The Mapledurham 1997 Trust, Mapledurham HOUSE, Reading, RG4 7TR. Pre-press and design by Tony Hadland E-mail: [email protected] Printed by Antony Rowe Limited, 2 Whittle Drive, Highfield Industrial Estate, Eastbourne, East Sussex, BN23 6QT. E-mail: [email protected] While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, neither the author nor the publisher can be held responsible for any loss or inconvenience arising from errors contained in this work. Feedback from readers on points of accuracy will be welcomed and should be e-mailed to [email protected] or mailed to the author via the publisher. Front cover: Mapledurham House, front elevation. Back cover: Mapledurham House, as seen from the Thames. A high gable end, clad in reflective oyster shells, indicated a safe house for Catholics. -

Cholsey and Caversham: Impacts on Protected Landscapes

Oxfordshire County Council Strategic Landscape Assessment of potential minerals working at Cholsey and Caversham: impacts on Protected Landscapes. February 2012 Oxfordshire Minerals and Waste LDF Landscape Study Contents 1 Aims and scope Background 1 Aims 1 Sites & scope 1 2 Methodology 2 Overview of Methodology 2 Assessment of landscape capacity 3 3 Policy Context 7 National Landscape Policy and Legislation 7 Regional policies 9 Oxfordshire policies 9 4 AONB plans and policies 11 Development affecting the setting of AONBs 11 Chilterns AONB policies and guidance 11 North Wessex Downs AONB policies and guidance 13 5 Cholsey 14 6 Caversham 24 7 Overall recommendations 33 Appendix 1: GIS datasets 34 Appendix 2:National Planning Policy Framework relating to 35 landscape and AONBs Appendix 2: Regional planning policies relating to landscape 37 Oxfordshire Minerals and Waste LDF Landscape Study Section 1. Aims and Scope Background 1.1 Oxfordshire’s draft Minerals and Waste Core Strategy was published for public consultation in September 2011. A concern was identified in the responses made by the Chilterns Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) and North Wessex Downs AONB. This related to potential landscape impacts on the Protected Landscapes of minerals developments within two proposed broad areas for sand and gravel working at Cholsey and Caversham. This study identifies the nature of these impacts, and potential mitigation measures which could help reduce the impacts. 1.2 The impacts identified will refer both to the operational phase of any development, and restoration phases. Recommendations may help to identify potential restoration priorities, and mitigation measures. Aims 1.3 The aim of the study is to carry out an assessment of the potential landscape impacts of minerals development within two proposed areas for mineral working on the setting of Oxfordshire’s AONBs. -

Crowmarsh Parish Neighbourhood Plan 2020-2035

CROWMARSH PARISH NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN 2020-2035 Submission version 1 Cover picture: Riverside Meadows Local Green Space (Policy CRP 6) 2 CROWMARSH PARISH NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN 2020-2035 Submission version CONTENTS page 1. Introduction 6 • The Parish Vision • Objectives of the Plan 2. The neighbourhood area 10 3. Planning policy context 21 4. Community views 24 5. Land use planning policies 27 • Policy CRP1: Village boundaries and infill development • Policy CRP2: Housing mix and tenure • Policy CRP3: Land at Howbery Park, Benson Lane, Crowmarsh Gifford • Policy CRP4: Conservation of the environment • Policy CRP5: Protection and enhancement of ecology and biodiversity • Policy CRP6: Green spaces 6. Implementation 42 Crowmarsh Parish Council January 2021 3 List of Figures 1. Designated area of Crowmarsh Parish Neighbourhood Plan 2. Schematic cross-section of groundwater flow system through Crowmarsh Gifford 3. Location of spring line and main springs 4. Environment Agency Flood risk map 5. Chilterns AONB showing also the Ridgeway National Trail 6. Natural England Agricultural Land Classification 7. Listed buildings in and around Crowmarsh Parish 8. Crowmarsh Gifford and the Areas of Natural Outstanding Beauty 9. Policies Map 9A. Inset Map A Crowmarsh Gifford 9B. Insert Map B Mongewell 9C. Insert Map C North Stoke 4 List of Appendices* 1. Baseline Report 2. Environment and Heritage Supporting Evidence 3. Housing Needs Assessment 4. Landscape Survey and Impact Assessment 5. Site Assessment Crowmarsh Gifford 6. Strategic Environment Assessment 7. Consultation Statement 8. Compliance Statement * Issued as a set of eight separate documents to accompany the Plan 5 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Neighbourhood Plans are a recently introduced planning document subsequent to the Localism Act, which came into force in April 2012. -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

Land at Winterbrook, Wallingford, Oxfordshire

Land at Winterbrook, Wallingford, Oxfordshire An Archaeological Evaluation for Berkeley Homes (Oxford and Chiltern) Ltd by James Lewis Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd Site Code WWO09/57 October 2009 Summary Site name: Land at Winterbrook, Wallingford, Oxfordshire Grid reference: SU6010 8840 Site activity: Field Evaluation Date and duration of project: 25th August – 10th October 2009 Project manager: Steve Ford Site supervisor: James Lewis Site code: WWO09/57 Area of site: 24 ha Summary of results: Evaluation trenching confirmed the presence of a number of archaeological features (some already identified from geophysical survey and aerial photographs) and showed that these span several phases of activity, but with an appreciable density only in the early Iron Age. The remains encountered may be considered typical of this part of the Thames Valley. Some zones within the site appeared to be of lower potential. Areas of high archaeological potential have already been excluded from the development area by design. Location and reference of archive: The archive is presently held at Thames Valley Archaeological Services, Reading and will be deposited at Oxfordshire County Museums Service in due course. This report may be copied for bona fide research or planning purposes without the explicit permission of the copyright holder Report edited/checked by: Steve Ford9 27.10.09 Steve Preston9 27.10.09 i Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd, 47–49 De Beauvoir Road, Reading RG1 5NR Tel. (0118) 926 0552; Fax (0118) 926 0553; email [email protected]; website: www.tvas.co.uk Land at Winterbrook, Wallingford, Oxfordshire An Archaeological Evaluation by James Lewis Report 09/57b Introduction This report documents the results of an archaeological field evaluation carried out on land at Winterbrook, Wallingford, Oxfordshire, SU6010 8840 (Fig. -

Rawlinson's Proposed History of Oxfordshire

Rawlinson's Proposed History of Oxfordshire By B. J. ENRIGHT INthe English Topographer, published in 1720, Richard Rawlinson described the manuscript and printed sources from which a history of Oxfordshire might be compiled and declared regretfully, ' of this County .. we have as yet no perfect Description.' He hastened to add in that mysteriously weH informed manner which invariably betokened reference to his own activities: But of this County there has been, for some Years past, a Description under Consideration, and great Materials have been collected, many Plates engraved, an actual Survey taken, and Quaeries publish'd and dispers'd over the County, to shew the Nature of the Design, as well to procure Informations from the Gentry and others, which have, in some measure, answer'd the Design, and encouraged the Undertaker to pursue it with all convenient Speed. In this Work will be included the Antiquities of the Town and City of Oxford, which Mr. Anthony d l-Vood, in Page 28 of his second Volume of Athenae Oxonienses, &c. promised, and has since been faithfully transcribed from his Papers, as well as very much enJarg'd and corrected from antient Original Authorities. I At a time when antiquarian studies were rapidly losing their appeal after the halcyon days of the 17th-century,' this attempt to compile a large-scale history of a county which had received so little attention caUs for investigation. In proposing to publish a history of Oxfordshirc at this time, Rawlinson was being far less unrealistic thall might at first appear. For -

The Complete Sedilia Handlist of England and Wales

Church Best image Sedilia Type Period County Diocese Archdeaconry Value Type of church Dividing element Seats Levels Features Barton-le-Clay NONE Classic Geo Bedfordshire LINCOLN BEDFORD £12 / 0 / 0 Parish 3 2 Bedford, St John the Baptist NONE Classic Dec Bedfordshire LINCOLN BEDFORD Attached shaft 3 1 Cap Framed Fig Biggleswade flickr Derek N Jones Classic Dec Bedfordshire LINCOLN BEDFORD £46 / 13 / 4 Parish, prebend, vicarage Detached shaft 3 3 Cap Blunham flickr cambridge lad1 Classic Dec Bedfordshire LINCOLN BEDFORD £20 / 0 / 0 Parish Detached shaft 3 3 Cap Caddington NONE Classic Geo Bedfordshire LINCOLN BEDFORD £16 / 0 / 0 Parish, prebend, vicarage Framed Clifton church site, c.1820 Classic Dec Bedfordshire LINCOLN BEDFORD £7 / 6 / 8 Parish Detached shaft 2 2 Croc Dunton NONE Classic Dec Bedfordshire NORWICH NORFOLK £10 / 0 / 0 Parish, vicarage, appropriated 3 Plain Higham Gobion NONE Classic Perp Bedfordshire LINCOLN BEDFORD £4 / 13 / 4 Parish 3 Goldington NONE Drop sill Perp Bedfordshire LINCOLN BEDFORD £2 / 13 / 4 Parish, vicarage, appropriated 2 2 Lower Gravenhurst waymarking.com Classic Dec Bedfordshire LINCOLN BEDFORD Detached shaft 2 1 Framed Luton flickr stiffleaf Classic Perp Bedfordshire LINCOLN BEDFORD £66 / 13 / 4 Parish, vicarage, appropriated Attached shaft 4 1 Cap Croc Framed Fig Shields Odell NONE Drop sill Perp Bedfordshire LINCOLN BEDFORD £13 / 6 / 8 Parish 3 3 Sandy church site Classic Perp Bedfordshire LINCOLN BEDFORD £13 / 6 / 8 Parish Detached shaft 3 3 Framed Sharnbrook N chapel NONE Classic Dec Bedfordshire -

Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxford Archdeacons’ Marriage Bond Extracts 1 1634 - 1849 Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1634 Allibone, John Overworton Wheeler, Sarah Overworton 1634 Allowaie,Thomas Mapledurham Holmes, Alice Mapledurham 1634 Barber, John Worcester Weston, Anne Cornwell 1634 Bates, Thomas Monken Hadley, Herts Marten, Anne Witney 1634 Bayleyes, William Kidlington Hutt, Grace Kidlington 1634 Bickerstaffe, Richard Little Rollright Rainbowe, Anne Little Rollright 1634 Bland, William Oxford Simpson, Bridget Oxford 1634 Broome, Thomas Bicester Hawkins, Phillis Bicester 1634 Carter, John Oxford Walter, Margaret Oxford 1634 Chettway, Richard Broughton Gibbons, Alice Broughton 1634 Colliar, John Wootton Benn, Elizabeth Woodstock 1634 Coxe, Luke Chalgrove Winchester, Katherine Stadley 1634 Cooper, William Witney Bayly, Anne Wilcote 1634 Cox, John Goring Gaunte, Anne Weston 1634 Cunningham, William Abbingdon, Berks Blake, Joane Oxford 1634 Curtis, John Reading, Berks Bonner, Elizabeth Oxford 1634 Day, Edward Headington Pymm, Agnes Heddington 1634 Dennatt, Thomas Middleton Stoney Holloway, Susan Eynsham 1634 Dudley, Vincent Whately Ward, Anne Forest Hill 1634 Eaton, William Heythrop Rymmel, Mary Heythrop 1634 Eynde, Richard Headington French, Joane Cowley 1634 Farmer, John Coggs Townsend, Joane Coggs 1634 Fox, Henry Westcot Barton Townsend, Ursula Upper Tise, Warc 1634 Freeman, Wm Spellsbury Harris, Mary Long Hanburowe 1634 Goldsmith, John Middle Barton Izzley, Anne Westcot Barton 1634 Goodall, Richard Kencott Taylor, Alice Kencott 1634 Greenville, Francis Inner -

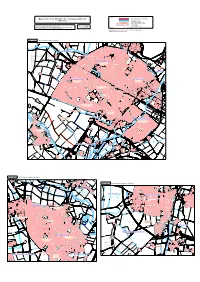

Map Referred to in the Oxfordshire

KEY Map referred to in the Oxfordshire (Electoral Changes) Order 2012 ELECTORAL DIVISION BOUNDARY WARD BOUNDARY Sheet 3 of 7 PARISH BOUNDARY PARISH WARD BOUNDARY BICESTER TOWN ED ELECTORAL DIVISION NAME BICESTER NORTH WARD WARD NAME This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of BICESTER CP PARISH NAME the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office © Crown copyright. Scale : 1cm = 0.08000 km Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Grid Interval 1km BICESTER WEST PARISH WARD PARISH WARD NAME The Local Government Boundary Commission for England GD100049926 2012. COINCIDENT BOUNDARIES ARE SHOWN AS THIN COLOURED LINES SUPERIMPOSED OVER WIDER ONES. SHEET 3, MAP 3A Electoral division boundaries in Bicester 1 2 4 4 A CAVERSFIELD CP Airfield Gliding Centre M U L L E I M CAVERSFIELD WARD N ULB ER R RY O A D D R IV E D R M A E B B U C N C BICESTER NORTH ED R R K A O N N E H L E L S (5) B R I O L A L D D R Recreation Ground L U Southwold C E County Primary R N School E S A U N V BICESTER NORTH WARD D S E E K R I N L M U Bardwell School A M N I E D N G BUCKNELL CP E BICESTER NORTH D IV D IS R R H D LIME CRESCENT L E PARISH WARD IV A N E N LA E S R W U IN B P DM U IL C L K AV N EN E U E L E V Glory Farm PLOUGHLEY ED L Bure Park I B R R Primary and Nursery R Primary School D O O W A B E School D A L (13) N L I N I N V B G R U D D E B R R A R M R Y LAUNTON WARD IV R O Y D E R S A L V O The Cooper School D E E A N I A O U D R E F D LAUNTON -

Issue 492 September 2019 Next Month's Issue ADVERTISING RATES the Crowmarsh News Team

Issue 492 September 2019 The Crowmarsh News is a self-funded publication, and we regret that we are The Crowmarsh News team unable to accept unpaid advertising, even The Crowmarsh News is run by the from local businesses and societies. Crowmarsh News Association, a group of We welcome material for inclusion but do local volunteers. not necessarily endorse the views of Editorial and Layout: Doug German and contributors. We reserve the right to refuse John Griffin material or to shorten contributions as may be appropriate: editorial decisions are final. Editorial support: James and Toni Taylor, Amanda Maher and Kirsty Dawson What’s on listings: Julian Park ADVERTISING RATES Advertising: Pat Shields The Crowmarsh News is distributed to over 700 households in Crowmarsh Distribution: Frank Sadler and team Gifford, North Stoke and Mongewell. Our rates for a one-eighth-page display advertisement (nominal 9cm wide x 7cm tall) are: Next month’s issue 1 month — £8.50 All new advertisements and all copy for the 3 months — £25.00 next issue of Crowmarsh News must reach 6 months — £45.00 us before our 20th September deadline. Leaflet distribution For all items of news, articles or For a single sheet loose insert in the correspondence, please e-mail Crowmarsh News (size up to A4), our [email protected] current rate is £30 for a single month. or deliver to the Editors at 57 The Street. Advertisers must supply their own inserts (740 copies please). For all advertising, please contact Cheques should be made payable to [email protected] Crowmarsh News Association. -

South Oxfordshire District Council – New Warding Arrangements

Council report Report of Chief Executive Author: David Buckle Telephone: E-mail: To: Council DATE: 30 August 2012 South Oxfordshire District Council – New Warding Arrangements Recommendation That Council agrees the submission to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England attached as Appendix A to this report Purpose of Report 1. This report invites Council to agree a submission to the Local Government Boundary Commission (LGBCE) for England on warding arrangements as it reduces in size from 48 to 36 members. Background 2. In March of this year the LGBCE commenced an electoral review at our request. In June it announced that it was minded to recommend (ultimately, parliament takes the decision) a council size of 36. This was the number that Council agreed to propose at it meeting in February. 3. The next stage of the review is to develop warding proposals. At this time the LGBCE has published nothing so we have a blank canvass on which to make proposals. However, the number of councillors we put forward must add up to 36 (or conceivably 35 or 37 if there are particular reasons justifying such a variation) and best comply with the three criteria that govern electoral reviews, all of which carry equal weight. These are: • to deliver electoral equality for voters • to provide boundaries that reflect natural communities • to provide effective and convenient local government 4. In November the LGBCE will publish its draft warding proposals and council will have an opportunity to decide its formal response to these at a meeting next X:\Committee Documents\2012-2013 Cycle (2) Aug-Oct\Council_300812\Council_300812_Warding arrangements 1 report.doc January. -

Berkshire, Buckinghamshire & Oxfordshire County Guide

Historic churches in Berkshire Buckinghamshire Oxfordshire experience the passing of time visitchurches.org.uk/daysout 3 absorb an atmosphere of tranquility Step inside some of the churches of the Thames Valley and the Chilterns and you’ll discover art and craftsmanship to rival that of a museum. 2 1 The churches of the Thames Valley and the Chilterns contain some remarkable treasures. Yet sometimes it’s not the craftsmanship but the atmosphere that fires the imagination – the way windows scatter gems of light on an old tiled floor, or the peace of a quiet corner that has echoed with prayer for centuries. All the churches in this leaflet have been saved by The Churches Conservation Trust. The Trust is a charity that cares for more than 340 churches in England. This is one of 18 leaflets that highlight their history and treasures. dragon slayer For more information on the other guides in this series, fiery dragons and fearless saints as well as interactive maps and downloadable information, come alive in dramatic colour at see visitchurches.org.uk St Lawrence, Broughton 5 Lower Basildon, St Bartholomew 1 Berkshire A riverside church built by the people, for the people • 13th-century church near a beautiful stretch of the Thames • Eight centuries of remarkable memorials This striking flint-and-brick church stands in a pretty churchyard by the Thames, filled with memorials to past parishioners and, in early spring, a host of daffodils. Jethro Tull, the father of modern farming, has a memorial here (although the whereabouts of his grave is unknown) and there is a moving marble statue of two young brothers drowned in the Thames in 1886.