Sir Winston Churchill - by Celia Lee - Page 21

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sevenoaks District Accommodation Availability List

Sevenoaks District Accommodation Availability List Eastern Sevenoaks: Chipstead, Crouch, Dunk’s Green, Ightham, Kemsing, Seal, Shipbourne, Stone Street, Wrotham Heath Western Sevenoaks: Brasted, Cowden, Edenbridge, Marsh Green Locations: Northern Sevenoaks: Dunton Green, Knockholt, Shoreham Southern Sevenoaks: Hildenborough, Tonbridge, Weald Central Sevenoaks: Sevenoaks town EASTERN SEVENOAKS : Chipstead, Crouch, Dunk’s Green, Ightham, Kemsing, Seal, Shipbourne, Stone Street, Wrotham Heath Current Availability 13 – 27 November 2017 Chipstead/ Crossways House Ensuite room or private Chevening Cross Rd Chevening £: 50 – 90; apartment £85 per night Please phone for latest bathroom near Chevening/Chipstead TN14 6HF availability 2 bed/2 bath self-catering Mrs Lela Weavers apartment for 6 Near Darent Valley Path & North T: 01732 456334 Downs Way. E: [email protected] Borough Green, Yew Tree Barn WiFi access Long Mill Lane (Crouch) £: 60 – 130 13 – 27 November Ensuite rooms Crouch Family rooms Borough Green TN15 8QB Tricia & James Barton Guest sitting rooms T: 01732 780461 or 07811 505798 Partial disabled room(s) Converted barn built around 1810 E: [email protected] located in a tranquil, secluded hamlet www.yewtreebarn.com with splendid views across open countryside. Excellent base for touring Kent, Sussex & London. Ightham The Studio at Double Dance Broadband Tonbridge Road £: 70 – 80 15 - 23 November WiFi access Ightham TN15 9AT Ensuite room A stylish self-contained annexe Penny Cracknell Kent Breakfast overlooking -

APPLE (Fruit Varieties)

E TG/14/9 ORIGINAL: English DATE: 2005-04-06 INTERNATIONAL UNION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NEW VARIETIES OF PLANTS GENEVA * APPLE (Fruit Varieties) UPOV Code: MALUS_DOM (Malus domestica Borkh.) GUIDELINES FOR THE CONDUCT OF TESTS FOR DISTINCTNESS, UNIFORMITY AND STABILITY Alternative Names:* Botanical name English French German Spanish Malus domestica Apple Pommier Apfel Manzano Borkh. The purpose of these guidelines (“Test Guidelines”) is to elaborate the principles contained in the General Introduction (document TG/1/3), and its associated TGP documents, into detailed practical guidance for the harmonized examination of distinctness, uniformity and stability (DUS) and, in particular, to identify appropriate characteristics for the examination of DUS and production of harmonized variety descriptions. ASSOCIATED DOCUMENTS These Test Guidelines should be read in conjunction with the General Introduction and its associated TGP documents. Other associated UPOV documents: TG/163/3 Apple Rootstocks TG/192/1 Ornamental Apple * These names were correct at the time of the introduction of these Test Guidelines but may be revised or updated. [Readers are advised to consult the UPOV Code, which can be found on the UPOV Website (www.upov.int), for the latest information.] i:\orgupov\shared\tg\applefru\tg 14 9 e.doc TG/14/9 Apple, 2005-04-06 - 2 - TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. SUBJECT OF THESE TEST GUIDELINES..................................................................................................3 2. MATERIAL REQUIRED ...............................................................................................................................3 -

Me Jane Tour Playbill-Final

The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN, Chairman DEBORAH F. RUTTER, President Kennedy Center Theater for Young Audiences on Tour presents A Kennedy Center Commission Based on the book Me…Jane by Patrick McDonnell Adapted and Written by Patrick McDonnell, Andy Mitton, and Aaron Posner Music and Lyrics by Andy Mitton Co-Arranged by William Yanesh Choreographed by Christopher D’Amboise Music Direction by William Yanesh Directed by Aaron Posner With Shinah Brashears, Liz Filios, Phoebe Gonzalez, Harrison Smith, and Michael Mainwaring Scenic Designer Lighting Designer Costume Designer Projection Designer Paige Hathaway Andrew Cissna Helen Q Huang Olivia Sebesky Sound Designer Properties Artisan Dramaturg Casting Director Justin Schmitz Kasey Hendricks Erin Weaver Michelle Kozlak Executive Producer General Manager Executive Producer Mario Rossero Harry Poster David Kilpatrick Bank of America is the Presenting Sponsor of Performances for Young Audiences. Additional support for Performances for Young Audiences is provided by the A. James & Alice B. Clark Foundation; The Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation; Paul M. Angell Family Foundation; Anne and Chris Reyes; and the U.S. Department of Education. Funding for Access and Accommodation Programs at the Kennedy Center is provided by the U.S. Department of Education. Major support for educational programs at the Kennedy Center is provided by David M. Rubenstein through the Rubenstein Arts Access Program. The contents of this document do not necessarily represent the policy of the U.S. Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government. " Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. -

Notable Australians Historical Figures Portrayed on Australian Banknotes

NOTABLE AUSTRALIANS HISTORICAL FIGURES PORTRAYED ON AUSTRALIAN BANKNOTES X X I NOTABLE AUSTRALIANS HISTORICAL FIGURES PORTRAYED ON AUSTRALIAN BANKNOTES Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are respectfully advised that this book includes the names and images of people who are now deceased. Cover: Detail from Caroline Chisholm's portrait by Angelo Collen Hayter, oil on canvas, 1852, Dixson Galleries, State Library of NSW (DG 459). Notable Australians Historical Figures Portrayed on Australian Banknotes © Reserve Bank of Australia 2016 E-book ISBN 978-0-6480470-0-1 Compiled by: John Murphy Designed by: Rachel Williams Edited by: Russell Thomson and Katherine Fitzpatrick For enquiries, contact the Reserve Bank of Australia Museum, 65 Martin Place, Sydney NSW 2000 <museum.rba.gov.au> CONTENTS Introduction VI Portraits from the present series Portraits from pre-decimal of banknotes banknotes Banjo Paterson (1993: $10) 1 Matthew Flinders (1954: 10 shillings) 45 Dame Mary Gilmore (1993: $10) 3 Charles Sturt (1953: £1) 47 Mary Reibey (1994: $20) 5 Hamilton Hume (1953: £1) 49 The Reverend John Flynn (1994: $20) 7 Sir John Franklin (1954: £5) 51 David Unaipon (1995: $50) 9 Arthur Phillip (1954: £10) 53 Edith Cowan (1995: $50) 11 James Cook (1923: £1) 55 Dame Nellie Melba (1996: $100) 13 Sir John Monash (1996: $100) 15 Portraits of monarchs on Australian banknotes Portraits from the centenary Queen Elizabeth II of Federation banknote (2016: $5; 1992: $5; 1966: $1; 1953: £1) 57 Sir Henry Parkes (2001: $5) 17 King George VI Catherine Helen -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Winston Churchill, the Morning Post and the End of the Imperial Romance Journal Item How to cite: Griffiths, Andrew (2013). Winston Churchill, the Morning Post and the End of the Imperial Romance. Victorian Periodicals Review, 46(2) pp. 163–183. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2013 The Research Society for Victorian Periodicals https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Accepted Manuscript Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1353/vpr.2013.0016 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Winston Churchill, the Morning Post and the End of the Imperial Romance. Brief Biography: Andrew Griffiths studied at the University of Exeter and teaches at Plymouth University and the Open University. His research addresses the relationship between New Imperialism, New Journalism and fiction in the late nineteenth century. He is currently working on a project which focuses on the role of the special correspondent at the heart of this relationship. Abstract: Winston Churchill’s Morning Post correspondence from Kitchener’s 1898 Sudan expedition documents a shift in the practice and reportage of imperialism. Sensational New Journalism and aggressive New Imperialism had been locked in a mutually-supportive relationship. Special correspondents, including Churchill, emphasised the romance of empire. -

THE CHURCHILLIAN Churchill Society of Tennessee 2Nd Summer Edition 2020

THE CHURCHILLIAN Churchill Society of Tennessee 2nd Summer Edition 2020 Sir Winston Churchill’s Statue Parliament Square London This 12-foot-tall bronze statue of Churchill in Parliament Square was designed by Ivor Roberts- Jones. The statue was dedicated in 1972 by Churchill’s wife Lady Churchill at a ceremony attended by HRH Queen Elizabeth II and four Prime Ministers. The location of the statue was chosen by Churchill himself and was inspired by that now-famous photo of him inspecting the bomb-damaged Chamber of the Commons in Westminster on May 11, 1941. The Churchillian Page 1 Inside this issue of the Churchillian Page 4. Farewell to the Earl Page 5. Coronavirus, the Queen and the 75th anniversary of VE Day. Dame Vera Lynn’s last article from the May 2020 issue of the Oldie Magazine Page 8. Lady Churchill’s Rose Garden, a special visit by Beryl Nicholson Page 10. A Tour of the Gardens at Chartwell House, beloved home of Sir Winston Churchill by Jim Drury Page 29. Why are the Churchill Statue and all our other monuments so important? A quote from Andrew Roberts Page 30. Resource Page The Churchillian Page 2 THE CHURCHILL SOCIETY OF TENNESSEE Patron: Randolph Churchill Board of Directors: Executive Committee: President: Jim Drury Vice President Secretary: Robin Sinclair PhD Vice President Treasurer: Richard Knight Esq Comptroller: The Earl of Eglinton & Winton, Hugh Montgomery - Robert Beck Don Cusic Beth Fisher Michael Shane Neal - Administrative officer: Lynne Siesser - Past President: Dr John Mather - Sister Chapter: Chartwell Branch, Westerham, Kent, England - Contact information: Churchillian Editor: Jim Drury www.churchillsocietytn.org Churchill Society of Tennessee PO BOX 150993 Nashville, TN 37215 USA 615-218-8340 The Churchillian Page 3 Farewell to the Earl! It is with regret that we must announce the departure of The Earl of Eglinton & Winton, the Rt. -

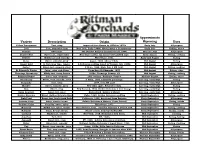

Variety Description Origin Approximate Ripening Uses

Approximate Variety Description Origin Ripening Uses Yellow Transparent Tart, crisp Imported from Russia by USDA in 1870s Early July All-purpose Lodi Tart, somewhat firm New York, Early 1900s. Montgomery x Transparent. Early July Baking, sauce Pristine Sweet-tart PRI (Purdue Rutgers Illinois) release, 1994. Mid-late July All-purpose Dandee Red Sweet-tart, semi-tender New Ohio variety. An improved PaulaRed type. Early August Eating, cooking Redfree Mildly tart and crunchy PRI release, 1981. Early-mid August Eating Sansa Sweet, crunchy, juicy Japan, 1988. Akane x Gala. Mid August Eating Ginger Gold G. Delicious type, tangier G Delicious seedling found in Virginia, late 1960s. Mid August All-purpose Zestar! Sweet-tart, crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1999. State Fair x MN 1691. Mid August Eating, cooking St Edmund's Pippin Juicy, crisp, rich flavor From Bury St Edmunds, 1870. Mid August Eating, cider Chenango Strawberry Mildly tart, berry flavors 1850s, Chenango County, NY Mid August Eating, cooking Summer Rambo Juicy, tart, aromatic 16th century, Rambure, France. Mid-late August Eating, sauce Honeycrisp Sweet, very crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1991. Unknown parentage. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Burgundy Tart, crisp 1974, from NY state Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Blondee Sweet, crunchy, juicy New Ohio apple. Related to Gala. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Gala Sweet, crisp New Zealand, 1934. Golden Delicious x Cox Orange. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Swiss Gourmet Sweet-tart, juicy Switzerland. Golden x Idared. Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Golden Supreme Sweet, Golden Delcious type Idaho, 1960. Golden Delicious seedling Early September Eating, cooking Pink Pearl Sweet-tart, bright pink flesh California, 1944, developed from Surprise Early September All-purpose Autumn Crisp Juicy, slow to brown Golden Delicious x Monroe. -

First Lady: the Life and Wars of Clementine Churchill Free Ebook

FREEFIRST LADY: THE LIFE AND WARS OF CLEMENTINE CHURCHILL EBOOK Sonia Purnell | 400 pages | 14 May 2015 | Aurum Press Ltd | 9781781313060 | English | London, United Kingdom Biography of Clementine Churchill, Britain's First Lady First Lady is a bold biography of a bold woman; at last Purnell has put Clementine Churchill at the centre of her own extraordinary story, rather than in the shadow of her husband's.' 'From the influence she wielded to the secrets she kept, a new book looks at the extraordinary role of Winston Churchill's wife Clementine who proved that behind. First Lady: the Life and Wars of Clementine Churchill, review: 'fascinating account of an under appreciated woman' Geoffrey Lyons reviews Sonia Purnell’s enthralling new biography of one of Britain’s most misunderstood figures. Keeping silent was, Purnell argues, Clementines most decisive and courageous action of the war. Anne Sebba is the author of American Jennie, The Remarkable Life of Lady Randolph Churchill (WW Norton ) and is currently writing Les Parisiennes: how Women lived, loved and died in Paris from for publication in First Lady: The Life and Wars of Clementine Churchill First Lady: the Life and Wars of Clementine Churchill, review: 'fascinating account of an under appreciated woman' Geoffrey Lyons reviews Sonia Purnell’s enthralling new biography of one of Britain’s most misunderstood figures. Royal Oak lecturer Sonia Purnell’s new book, “First Lady: the Life and Wars of Clementine Churchill,” is out to rave reviews. Examining Clementine’s role in some of the critical events of the 20th century, Purnell retells a history that has largely marginalized Sir Winston’s wife. -

The Attlee Governments

Vic07 10/15/03 2:11 PM Page 159 Chapter 7 The Attlee governments The election of a majority Labour government in 1945 generated great excitement on the left. Hugh Dalton described how ‘That first sensa- tion, tingling and triumphant, was of a new society to be built. There was exhilaration among us, joy and hope, determination and confi- dence. We felt exalted, dedication, walking on air, walking with destiny.’1 Dalton followed this by aiding Herbert Morrison in an attempt to replace Attlee as leader of the PLP.2 This was foiled by the bulky protection of Bevin, outraged at their plotting and disloyalty. Bevin apparently hated Morrison, and thought of him as ‘a scheming little bastard’.3 Certainly he thought Morrison’s conduct in the past had been ‘devious and unreliable’.4 It was to be particularly irksome for Bevin that it was Morrison who eventually replaced him as Foreign Secretary in 1951. The Attlee government not only generated great excitement on the left at the time, but since has also attracted more attention from academics than any other period of Labour history. Foreign policy is a case in point. The foreign policy of the Attlee government is attractive to study because it spans so many politically and historically significant issues. To start with, this period was unique in that it was the first time that there was a majority Labour government in British political history, with a clear mandate and programme of reform. Whereas the two minority Labour governments of the inter-war period had had to rely on support from the Liberals to pass legislation, this time Labour had power as well as office. -

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

East of Suez and the Commonwealth 1964–1971 (In Three Parts, 2004)

00-Suez-Blurb-pp 21/9/04 11:32 AM Page 1 British Documents on the End of Empire Project Volumes Published and Forthcoming Series A General Volumes Series B Country Volumes Vol 1 Imperial Policy and Vol 1 Ghana (in two parts, 1992) Colonial Practice Vol 2 Sri Lanka (in two parts, 1997) 1925–1945 (in two parts, 1996) Vol 3 Malaya (in three parts, 1995) Vol 2 The Labour Government and Vol 4 Egypt and the Defence of the the End of Empire 1945–1951 Middle East (in three parts, 1998) (in four parts, 1992) Vol 5 Sudan (in two parts, 1998) Vol 3 The Conservative Government Vol 6 The West Indies (in one part, and the End of Empire 1999) 1951–1957 (in three parts, 1994) Vol 7 Nigeria (in two parts, 2001) Vol 4 The Conservative Government Vol 8 Malaysia (in one part, 2004) and the End of Empire 1957–1964 (in two parts, 2000) Vol 5 East of Suez and the Commonwealth 1964–1971 (in three parts, 2004) ● Series A is complete. Further country volumes in series B are in preparation on Kenya, Central Africa, Southern Africa, the Pacific (Fiji), and the Mediterranean (Cyprus and Malta). The Volume Editors S R ASHTON is Senior Research Fellow and General Editor of the British Documents on the End of Empire Project, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London. With S E Stockwell he edited Imperial Policy and Colonial Practice 1925–1945 (BDEEP, 1996), and with David Killingray The West Indies (BDEEP, 1999). Wm ROGER LOUIS is Kerr Professor of English History and Culture and Distinguished Teaching Professor, University of Texas at Austin, USA, and an Honorary Fellow of St Antony’s, Oxford. -

Catalogue 244: the Churchills 1 15

The Churchills Catalogue 244 July 2021 ABOUT THIS CATALOGUE Most of the books in this catalogue are from the private library of the late The Hon. David Levine AO RFD QC. Most carry his bookplate or book label, usually affixed to the upper pastedown or upper free endpaper. TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF SALE Unless otherwise described, all books are in the original cloth or board binding, and are in very good, or better, condition with defects, if any, fully described. Our prices are nett, and quoted in Australian dollars. Traditional trade terms apply. Items are offered subject to prior sale. All orders will be confirmed by email. PAYMENT OPTIONS We accept the major credit cards, PayPal, and direct deposit to the following account: Account name: Kay Craddock Antiquarian Bookseller Pty Ltd BSB: 083 004 Account number: 87497 8296 Should you wish to pay by cheque we may require the funds to be cleared before items are sent. GUARANTEE As a member or affiliate of the associations listed below, we embrace the time-honoured traditions and courtesies of the book trade. We also uphold the highest standards of business principles and ethics, including your right to privacy. Under no circumstances will we disclose any of your personal information to a third party, unless your specific permission is given. TRADE ASSOCIATIONS Australian and New Zealand Association of Antiquarian Booksellers [ANZAAB] Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association [ABA(Int)] International League of Antiquarian Booksellers [ILAB] Australian Booksellers Association REFERENCES CITED Cohen: Bibliography of the Writings of Sir Winston Churchill. By Ronald Cohen. In three volumes. Thoemmes Continuum, London, 2006.