Crassostrea Gigas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colonial Tunicates: Species Guide

SPECIES IN DEPTH Colonial Tunicates Colonial Tunicates Tunicates are small marine filter feeder animals that have an inhalant siphon, which takes in water, and an exhalant siphon that expels water once it has trapped food particles. Tunicates get their name from the tough, nonliving tunic formed from a cellulose-like material of carbohydrates and proteins that surrounds their bodies. Their other name, sea squirts, comes from the fact that many species will shoot LambertGretchen water out of their bodies when disturbed. Massively lobate colony of Didemnum sp. A growing on a rope in Sausalito, in San Francisco Bay. A colony of tunicates is comprised of many tiny sea squirts called zooids. These INVASIVE SEA SQUIRTS individuals are arranged in groups called systems, which form interconnected Star sea squirts (Botryllus schlosseri) are so named because colonies. Systems of these filter feeders the systems arrange themselves in a star. Zooids are shaped share a common area for expelling water like ovals or teardrops and then group together in small instead of having individual excurrent circles of about 20 individuals. This species occurs in a wide siphons. Individuals and systems are all variety of colors: orange, yellow, red, white, purple, grayish encased in a matrix that is often clear and green, or black. The larvae each have eight papillae, or fleshy full of blood vessels. All ascidian tunicates projections that help them attach to a substrate. have a tadpole-like larva that swims for Chain sea squirts (Botryloides violaceus) have elongated, less than a day before attaching itself to circular systems. Each system can have dozens of zooids. -

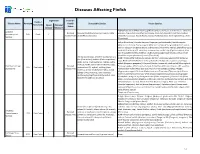

Diseases Affecting Finfish

Diseases Affecting Finfish Legislation Ireland's Exotic / Disease Name Acronym Health Susceptible Species Vector Species Non-Exotic Listed National Status Disease Measures Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), crucian carp (C. carassius), Epizootic Declared Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), redfin common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Haematopoietic EHN Exotic * Disease-Free perch (Percha fluviatilis) Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench Necrosis (Tinca tinca) Beluga (Huso huso), Danube sturgeon (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii), Sterlet sturgeon (Acipenser ruthenus), Starry sturgeon (Acipenser stellatus), Sturgeon (Acipenser sturio), Siberian Sturgeon (Acipenser Baerii), Bighead carp (Aristichthys nobilis), goldfish (Carassius auratus), Crucian carp (C. carassius), common carp and koi carp (Cyprinus carpio), silver carp (Hypophtalmichthys molitrix), Chub (Leuciscus spp), Roach (Rutilus rutilus), Rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus), tench (Tinca tinca) Herring (Cupea spp.), whitefish (Coregonus sp.), North African catfish (Clarias gariepinus), Northern pike (Esox lucius) Catfish (Ictalurus pike (Esox Lucius), haddock (Gadus aeglefinus), spp.), Black bullhead (Ameiurus melas), Channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), Pangas Pacific cod (G. macrocephalus), Atlantic cod (G. catfish (Pangasius pangasius), Pike perch (Sander lucioperca), Wels catfish (Silurus glanis) morhua), Pacific salmon (Onchorhynchus spp.), Viral -

Pathogens Table 2006

Important pathogens and parasites of molluscs Genetic and Pathology Laboratory Pathogen or parasite Host species Host impact Geographical distribution Infection period Diagnostic Cycle Species Group Denmark, Netherland, Incubation period : 3-4 month Ostrea edulis, O. Parasite of oyster haemocytes Throughout the year France, Ireland, Great Britain in infected area. Histology, Bonamia ostreae Protozoan Conchaphila, O. Angasi, O. (=>all the tissues can be invaded). (with a peak in Direct (except Scotland), Italy, tissue imprint, PCR, ISH, Puelchana, Tiostrea chilensis Oyster mortality September) Spain and USA electron microscopy Parasite of oyster haemocytes Throughout the year Histology, tissue imprint, Ostrea angasi, Ostrea Australia, New Zéland, Bonamia exitiosa Protozoan (=>all the tissues can be invaded). (with a peak during PCR, ISH, electron Unknown chilensis, Ostrea edulis Tasmania, Spain (in 2007) Oyster mortality Australian autumn) microscopy Parasites present in connective Histology, tissue imprint, Haplosporidium tissue (mantle, gonads, digestive Protozoan Crassostrea virginica USA, Canada Spring-summer PCR, ISH, electron Unknown costale gland) but not in digestive tubule microscopy epithelia. Mortality in May-June Parasites present in gills, connective tissue. Sporulation only Histology, tissue imprint, Unknown but Haplosporidium Crassostrea virginica, USA, Canada, Japan, Korea, Summer (May until Protozoan in the epithelium of digestive gland smear, PCR, HIS, electron intermediate host is nelsoni Crassostrea gigas France October) in C. virginica, Mortalities in C. microscopy suspected virginica. No mortality in C. gigas Parasite present in connective Haplosporidium Protozoan O. edulis, O. angasi tissue. Sometimes, mortality can France, Netherland, Spain Histology, tissue imprint Unknown armoricanum be observed Ostrea edulis , Tiostrea Spring-summer Histology, tissue imprint, ISH, Intermediate host: Extracellular parasite of the Marteilia refringens Protozoan chilensis, O. -

Structure of Protistan Parasites Found in Bivalve Molluscs

W&M ScholarWorks VIMS Books and Book Chapters Virginia Institute of Marine Science 1988 Structure of Protistan Parasites Found in Bivalve Molluscs Frank O. Perkins Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsbooks Part of the Marine Biology Commons, and the Parasitology Commons American Fisheries Society Special Publication 18:93- 111 , 1988 CC> Copyrighl by !he American Fisheries Sociely 1988 PARASITE MORPHOLOGY, STRATEGY, AND EVOLUTION Structure of Protistan Parasites Found in Bivalve Molluscs 1 FRANK 0. PERKINS Virginia In stitute of Marine Science. School of Marine Science, College of William and Mary Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062, USA Abstral'I.-The literature on the structure of protists parasitizing bivalve molluscs is reviewed, and previously unpubli shed observations of species of class Perkinsea, phylum Haplosporidia, and class Paramyxea are presented. Descriptions are given of the flagellar apparatus of Perkin.His marinus zoospores, the ultrastructure of Perkinsus sp. from the Baltic macoma Maconw balthica, and the development of haplosporosome-like bodies in Haplosporidium nelsoni. The possible origin of stem cells of Marreilia sydneyi from the inner two sporoplasms is discussed. New research efforts are suggested which could help elucidate the phylogenetic interrelationships and taxonomic positions of the various taxa and help in efforts to better understand life cycles of selected species. Studies of the structure of protistan parasites terization of the parasite species, to elucidation of found in bivalve moll uscs have been fruitful to the many parasite life cycles, and to knowledge of morphologist interested in comparative morphol- parasite metabolism. The latter, especially, is ogy, evolu tion, and taxonomy. -

Optimization of in Vitro Fertilization Using Cryopreserved Sperm of Crassostrea Angulata and Establishment of a Cryopreservation Protocol for Chamelea Gallina

Ana Luísa Lopes Santos Optimization of in vitro fertilization using cryopreserved sperm of Crassostrea angulata and establishment of a cryopreservation protocol for Chamelea gallina UNIVERSIDADE DO ALGARVE FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS E TECNOLOGIA 2018 Ana Luísa Lopes Santos Optimization of in vitro fertilization using cryopreserved sperm of Crassostrea angulata and establishment of a cryopreservation protocol for Chamelea gallina Thesis for Master Degree in Aquaculture and Fisheries Specialization Aquaculture Thesis supervision by: Professora Doutora Elsa Cabrita, CCMAR, Universidade do Algarve Dra Catarina Anjos, CCMAR, Universidade do Algarve UNIVERSIDADE DO ALGARVE FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS E TECNOLOGIA 2018 ii “Declaro ser a autora deste trabalho, que é original e inédito. Autores e trabalhos consultados estão devidamente citados no texto e constam da listagem de referências incluída.” ________________________________________________ Ana Luísa Lopes Santos Copyright © “A Universidade do Algarve tem o direito, perpétuo e sem limites geográficos, de arquivar e publicitar este trabalho através de exemplares impressos reproduzidos em papel ou de forma digital, ou por qualquer outro meio conhecido ou que venha a ser inventado, de o divulgar através de repositórios científicos e de admitir a sua cópia e distribuição com objetivos educacionais ou de investigação, não comerciais, desde que seja dado crédito ao autor e editor.” iii Eles não sabem, nem sonham, que o sonho comanda a vida, que sempre que um homem sonha o mundo pula e avança como bola colorida entre as mãos de uma criança.” António Gedeão iv This work was supported by VENUS Project (0139_VENUS_5_E) “Estudio Integral de los bancos naturales de moluscos bivalvos en el Golfo de Cádiz para su gestión sostenible y la conservación de sus hábitats asociados”. -

Data From: Microplastic Concentrations in Two Oregon Bivalve Species: Spatial, Temporal, and Species Variability

Portland State University PDXScholar Environmental Science and Management Datasets Environmental Science and Management 7-2019 Data From: Microplastic Concentrations in Two Oregon Bivalve Species: Spatial, Temporal, and Species Variability Britta Baechler Portland State University, [email protected] Elise F. Granek Portland State University, [email protected] Matthew V. Hunter Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Kathleen E. Conn United States Geological Survey Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/esm_data Part of the Environmental Health and Protection Commons, Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, and the Environmental Monitoring Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Baechler, Britta; Granek, Elise F.; Hunter, Matthew V.; and Conn, Kathleen E., "Microplastic Concentrations in Two Oregon Bivalve Species: Spatial, Temporal, and Species Variability" (2019). [Dataset]. https://doi.org/10.15760/esm-data.1 This Dataset is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Environmental Science and Management Datasets by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Metadata template1 for datasets of L&O-Letters articles Table 1. Description of the fields needed to describe the creation of your dataset. Title of dataset Microplastic Concentrations in Two Oregon Bivalve Species: Spatial, Temporal, and Species Variability URL of dataset Data is available in the Portland State University PDXScholar data repository at: https://doi.org/10.15760/esm-data.1 Abstract Microplastics are an ecological stressor with implications for ecosystem and human health when present in seafood. -

The Immune Response of the Scallop Argopecten Purpuratus Is Associated with Changes in the Host Microbiota Structure and Diversity T

Fish and Shellfish Immunology 91 (2019) 241–250 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Fish and Shellfish Immunology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/fsi Full length article The immune response of the scallop Argopecten purpuratus is associated with changes in the host microbiota structure and diversity T K. Muñoza, P. Flores-Herreraa, A.T. Gonçalvesb, C. Rojasc, C. Yáñezc, L. Mercadoa, K. Brokordtd, ∗ P. Schmitta, a Laboratorio de Genética e Inmunología Molecular, Instituto de Biología, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Valparaíso, Chile b Laboratorio de Biotecnología y Genómica Acuícola – Centro Interdisciplinario para la Investigación Acuícola (INCAR), Universidad de Concepción, Concepción, Chile c Laboratorio de Microbiología, Instituto de Biología, Facultad de Ciencias, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Valparaíso, Chile d Laboratory of Marine Physiology and Genetics (FIGEMA), Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Zonas Áridas (CEAZA) and Universidad Católica del Norte, Coquimbo, Chile ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: All organisms live in close association with a variety of microorganisms called microbiota. Furthermore, several 16S rDNA deep amplicon sequencing studies support a fundamental role of the microbiota on the host health and homeostasis. In this context, the aim Host-microbiota interactions of this work was to determine the structure and diversity of the microbiota associated with the scallop Argopecten Scallop purpuratus, and to assess changes in community composition and diversity during the host immune response. To Innate immune response do this, adult scallops were immune challenged and sampled after 24 and 48 h. Activation of the immune Antimicrobial effectors response was established by transcript overexpression of several scallop immune response genes in hemocytes and gills, and confirmed by protein detection of the antimicrobial peptide big defensin in gills of Vibrio-injected scallops at 24 h post-challenge. -

Olympia Oyster (Ostrea Lurida)

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Olympia Oyster Ostrea lurida in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2011 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2011. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Olympia Oyster Ostrea lurida in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xi + 56 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous report(s): COSEWIC. 2000. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Olympia Oyster Ostrea conchaphila in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 30 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm) Gillespie, G.E. 2000. COSEWIC status report on the Olympia Oyster Ostrea conchaphila in Canada in COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Olympia Oyster Ostrea conchaphila in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-30 pp. Production note: COSEWIC acknowledges Graham E. Gillespie for writing the provisional status report on the Olympia Oyster, Ostrea lurida, prepared under contract with Environment Canada and Fisheries and Oceans Canada. The contractor’s involvement with the writing of the status report ended with the acceptance of the provisional report. Any modifications to the status report during the subsequent preparation of the 6-month interim and 2-month interim status reports were overseen by Robert Forsyth and Dr. Gerald Mackie, COSEWIC Molluscs Specialist Subcommittee Co-Chair. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur l’huître plate du Pacifique (Ostrea lurida) au Canada. -

Assessment of the Aquacultural Potential of the Portuguese Oyster Crassostrea Angulata

Assessment of the aquacultural potential of the Portuguese oyster Crassostrea angulata Frederico Miguel Mota Batista Dissertação de doutoramento em Ciências do Meio Aquático 2007 Frederico Miguel Mota Batista Assessment of the aquacultural potential of the Portuguese oyster Crassostrea angulata Dissertação de Candidatura ao grau de Doutor em Ciências do Meio Aquático submetida ao Instituto de Ciências Biomédicas de Abel Salazar da Universidade do Porto. Orientador – Doutor Pierre Boudry Categoria – Investigador Afiliação – “Institut Français de Recherche pour l’Exploitation de la Mer” Co-orientador – Professora Doutora Maria Armanda Henriques Categoria –Professora catedrática Afiliação – Instituto de Ciências Biomédicas Abel Salazar da Universidade do Porto. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to thank Dr. Pierre Boudry for accepting to supervise this work, for your commitment and for providing me all conditions that made possible this work. Thank you also for your guidance and at the same time for giving me the freedom to make my own decisions which helped me to become a more independent researcher. Gostaria de agradecer à minha co-orientadora, a Professora Doutora Maria Armanda Henriques por me ter aceite como seu aluno de doutoramento e pela disponibilidade. Gostaria de agradecer ao Dr. Carlos Costa Monteiro por ter permitido a realização de parte deste trabalho na estação experimental de moluscicultura de Tavira do Instituto Nacional de Investigação Agrária e das Pescas (INIAP/IPIMAR). Gostaria também de agradecer-lhe pela disponibilidade e incentivo durante o desenrolar do doutoramento. Je remercie Dr. Philippe Goulletquer et Dr. Tristan Renault pour m’avoir accueillie au sein du Laboratoire de Génétique et Pathologie de la Station de La Tremblade de l’Institut Français de Recherche pour l’Exploitation de la Mer (IFREMER). -

Effect of Colonial Tunicate Presence on Ciona Intestinalis Recruitment Within a Mussel Farming Environment

Management of Biological Invasions (2012) Volume 3, Issue 1: 15–23 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3391/mbi.2012.3.1.02 Open Access © 2012 The Author(s). Journal compilation © 2012 REABIC Research Article Effect of colonial tunicate presence on Ciona intestinalis recruitment within a mussel farming environment S. Christine Paetzold1, Donna J. Giberson2, Jonathan Hill1, John D.P. Davidson1 and Jeff Davidson1 1 Department of Health Management, Atlantic Veterinary College, University of Prince Edward Island, 550 University Avenue, Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island C1A 4P3, Canada 2 Department of Biology, University of Prince Edward Island, 550 University Avenue, Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island C1A 4P3, Canada E-mail: [email protected] (SCP), [email protected] (DJG), [email protected] (JH), [email protected] (JDPD), [email protected] (JD) *Corresponding author Received: 4 November 2011 / Accepted: 7 August 2012 / Published online: 15 December 2012 Handling editor: Elias Dana, University of Almeria, Spain Abstract Aquatic invasive species decrease yields and increase costs in aquaculture operations worldwide. Anecdotal evidence from Prince Edward Island (PEI, Canada) estuaries suggested that recruitment of the non-indigenous solitary tunicate Ciona intestinalis may be lower on aquaculture gear where colonial tunicates (Botryllus schlosseri and Botrylloides violaceus) are already present. We tested this interspecific competition hypothesis by comparing C. intestinalis recruitment on un-fouled settlement plates to those pre-settled with Botryllus schlosseri or Botrylloides violaceus. C. intestinalis occurred on all plates after 2 month, but it was much more abundant (~80% coverage) on unfouled plates than on pre-settled plates (<10% coverage). However, C. intestinalis showed higher individual growth on pre-settled plates than on unfouled plates. -

Title the Anatomy of the Pacific Oyster, Crassostrea Gigas (Thurnberg

The Anatomy of the Pacific Oyster, Crassostrea gigas Title (Thurnberg)(Bivalvia : Ostreidae) Author(s) Evseev, G. A.; Yakovlev, Yu. M.; Li, Xiaoxu PUBLICATIONS OF THE SETO MARINE BIOLOGICAL Citation LABORATORY (1996), 37(3-6): 239-255 Issue Date 1996-12-25 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/176265 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University Pub!. Seto Mar. Bioi. Lab., 37(3/6): 239-255, 1996 239 The Anatomy of the Pacific Oyster, Crassostrea gigas (Thurnberg) (Bivalvia: Ostreidae) G.A. EVSEEV, Yu. M. Y AKOVLEV Institute of Marine Biology, Far East Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, Vladivostok 690041, Russia and XrAoxu Lr Institute of Oceanology, Academia Sinica, Qingdao 266071, P.R. China Abstract The anatomy of the soft body parts of the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas is presented. Anatomical features of mantles, gills, labial palps, pericardia! cavity, heart, oesophagus, stomach, gastric shield, crystalline style sac and intestine are described in detail. These structure in C. gigas are compared with those in closely related species. We suggest that some anatomical features provide taxonomic charac teristics that may be used to distinguish C. gigas from morphologically similar species within and between genera. Key words: Crassostrea gigas, soft organ morphology, taxonomy Introduction The morphological features of the shells have been used extensively in oyster taxonomy. However, the utility of shell features in oyster taxonomy is limited by the high level of their intra-specific variation (Tchang Si & Lou Tze-Kong, 1956; Menzel, 1973). The use of shell structural features in oyster taxonomy is particularly problematic between morphologically similar species from the genera Crassostrea and Saccostrea. -

Styela Clava (Tunicata, Ascidiacea) – a New Threat to the Mediterranean Shellfish Industry?

Aquatic Invasions (2009) Volume 4, Issue 1: 283-289 This is an Open Access article; doi: 10.3391/ai.2009.4.1.29 © 2009 The Author(s). Journal compilation © 2009 REABIC Special issue “Proceedings of the 2nd International Invasive Sea Squirt Conference” (October 2-4, 2007, Prince Edward Island, Canada) Andrea Locke and Mary Carman (Guest Editors) Short communication Styela clava (Tunicata, Ascidiacea) – a new threat to the Mediterranean shellfish industry? Martin H. Davis* and Mary E. Davis Fawley Biofouling Services, 45, Megson Drive, Lee-on-the-Solent, Hampshire, PO13 8BA, UK * Corresponding author E-mail: [email protected] Received 29 January 2008; accepted for special issue 17 April 2008; accepted in revised form 17 December 2008; published online 16 January 2009 Abstract The solitary ascidian Styela clava Herdman, 1882 has recently been found in the Bassin de Thau, France, an area of intensive oyster and mussel farming. The shellfish are grown on ropes suspended in the water column, similar to the technique employed in Prince Edward Island (PEI), Canada. S. clava is considered a major threat to the mussel industry in PEI but, at present, it is not considered a threat to oyster production in the Bassin de Thau. Anoxia or the combined effect of high water temperature and high salinity may be constraining the growth of the S. clava population in the Bassin de Thau. Identification of the factors restricting the population growth may provide clues to potential control methods. Key words: Styela clava, shellfish farming, Bassin de Thau Introduction Subsequent examination confirmed that the specimens were Styela clava Herdman, 1882 The solitary ascidian Styela clava is native to the (Davis and Davis 2008).