Boyle Renaissance Historical Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sheppard Block 10314 - 82 Ave, Edmonton, Ab

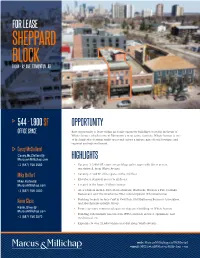

FOR LEASE SHEPPARD BLOCK 10314 - 82 AVE, EDMONTON, AB 544 - 1,900 SF OPPORTUNITY OFFICE SPACE Rare opportunity to lease within an iconic character building located in the heart of Whyte Avenue, which is one of Edmonton’s most iconic districts. Whyte Avenue is one of the highest pedestrian traffic areas and enjoys a unique mix of local boutique and regional and national tenant. Casey McClelland Casey.McClelland@ HIGHLIGHTS MarcusmMillichap.com +1 (587) 756 1560 • Vacancy 1: 1,900 SF, entire second floor office space with direct access, via stairwell, from Whyte Avenue • Vacancy 2: 544 SF office space on the 3rd floor Mike Hoffert • Elevator & stairwell access to all floors Mike.Hoffert@ MarcusMillichap.com • Located in the heart of Whyte Avenue +1 (587) 756 1550 • Area retailers include El Cortez restaurant, Starbucks, Hudson’s Pub, Dorinku Restaurant, and The Strathcona Hotel redevelopment (The Strathcona) • Building tenants include Craft & Cork Pub, Old Strathcona Business Association, Kevin Glass and Merchant Hospitality Group Kevin.Glass@ • Prime exposure commercial space in character building on Whyte Avenue MarcusMillichap.com • Building substantially renovated in 1995 to include elevator, sprinklers, new +1 (587) 756 1570 mechanical, etc. • Exposure to over 24,685 vehicles per day along Whyte Avenue web: MarcusMillichap.ca/MGHretail email: [email protected] TENANT LIST + STATS / SHEPPARD BLOCK 10314 - 82 AVE, EDMONTON, AB FLOOR UNIT SIZE TENANT U of A 5 minutes Basement BSMT 1,754 SF Craft & Cork Main Floor 100 2,150 -

WINTER 2015/2016! This Guide Gets Bigger and Better Every Year! We’Ve Packed This Year’S Winter Excitement Guide with Even More Events and Festivals

WELCOME TO WINTER 2015/2016! This guide gets bigger and better every year! We’ve packed this year’s Winter Excitement Guide with even more events and festivals. But keep your toque-covered ear to the ground for the spontaneous events that happen, like last year’s awesome #yegsnowfight We’re all working together, as a community, to think differently, to embrace the beauty of our snowy season, and to make Edmonton a great winter city. Edmonton’s community-led, award-winning WinterCity Strategy is our roadmap for reaching greatness. We are truly proud to say that we are on our way to realizing all the great potential our winters have to offer. New for this winter, we’ve got a blog for sharing ideas and experiences! Check it out at www.wintercityedmonton.ca If you haven’t joined us on Facebook and Twitter yet, we invite you to join the conversation. Let us know how you celebrate winter and be a part of the growing community that’s making Edmonton a great place to live, work and play in the wintertime. Now get out there and have some wintry fun! www.edmonton.ca/wintercitystrategy Facebook.com/WinterCityEdmonton @WinterCityYEG / #wintercityyeg Edmonton Ski Club Winter Warm-up Fundraiser Saturday, Oct 3, 2015 Edmonton Ski Club (9613 – 96 Avenue) www.edmontonskiclub.com Start winter with the ESC Winter Warm-up Fundraiser! Join us for a pig roast and family games. Visit our website for more details. International Walk to School Week (iWALK) Oct 5 – 9, 2015 www.shapeab.com iWALK is part of the Active & Safe Routes to School Program, promoting active travel to school! You can register online. -

Alberta Hansard

Province of Alberta The 30th Legislature Second Session Alberta Hansard Tuesday afternoon, April 20, 2021 Day 100 The Honourable Nathan M. Cooper, Speaker Legislative Assembly of Alberta The 30th Legislature Second Session Cooper, Hon. Nathan M., Olds-Didsbury-Three Hills (UC), Speaker Pitt, Angela D., Airdrie-East (UC), Deputy Speaker and Chair of Committees Milliken, Nicholas, Calgary-Currie (UC), Deputy Chair of Committees Aheer, Hon. Leela Sharon, Chestermere-Strathmore (UC) Nally, Hon. Dale, Morinville-St. Albert (UC), Allard, Tracy L., Grande Prairie (UC) Deputy Government House Leader Amery, Mickey K., Calgary-Cross (UC) Neudorf, Nathan T., Lethbridge-East (UC) Armstrong-Homeniuk, Jackie, Nicolaides, Hon. Demetrios, Calgary-Bow (UC) Fort Saskatchewan-Vegreville (UC) Nielsen, Christian E., Edmonton-Decore (NDP) Barnes, Drew, Cypress-Medicine Hat (UC) Nixon, Hon. Jason, Rimbey-Rocky Mountain House-Sundre (UC), Bilous, Deron, Edmonton-Beverly-Clareview (NDP) Government House Leader Carson, Jonathon, Edmonton-West Henday (NDP) Nixon, Jeremy P., Calgary-Klein (UC) Ceci, Joe, Calgary-Buffalo (NDP) Notley, Rachel, Edmonton-Strathcona (NDP), Copping, Hon. Jason C., Calgary-Varsity (UC) Leader of the Official Opposition Dach, Lorne, Edmonton-McClung (NDP), Orr, Ronald, Lacombe-Ponoka (UC) Official Opposition Deputy Whip Pancholi, Rakhi, Edmonton-Whitemud (NDP) Dang, Thomas, Edmonton-South (NDP), Official Opposition Deputy House Leader Panda, Hon. Prasad, Calgary-Edgemont (UC) Deol, Jasvir, Edmonton-Meadows (NDP) Phillips, Shannon, Lethbridge-West (NDP) Dreeshen, Hon. Devin, Innisfail-Sylvan Lake (UC) Pon, Hon. Josephine, Calgary-Beddington (UC) Eggen, David, Edmonton-North West (NDP), Rehn, Pat, Lesser Slave Lake (Ind) Official Opposition Whip Reid, Roger W., Livingstone-Macleod (UC) Ellis, Mike, Calgary-West (UC), Renaud, Marie F., St. -

Steward : 75 Years of Alberta Energy Regulation / the Sans Serif Is Itc Legacy Sans, Designed by Gordon Jaremko

75 years of alb e rta e ne rgy re gulation by gordon jaremko energy resources conservation board copyright © 2013 energy resources conservation board Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication ¶ This book was set in itc Berkeley Old Style, designed by Frederic W. Goudy in 1938 and Jaremko, Gordon reproduced in digital form by Tony Stan in 1983. Steward : 75 years of Alberta energy regulation / The sans serif is itc Legacy Sans, designed by Gordon Jaremko. Ronald Arnholm in 1992. The display face is Albertan, which was originally cut in metal at isbn 978-0-9918734-0-1 (pbk.) the 16 point size by Canadian designer Jim Rimmer. isbn 978-0-9918734-2-5 (bound) It was printed and bound in Edmonton, Alberta, isbn 978-0-9918734-1-8 (pdf) by McCallum Printing Group Inc. 1. Alberta. Energy Resources Conservation Board. Book design by Natalie Olsen, Kisscut Design. 2. Alberta. Energy Resources Conservation Board — History. 3. Energy development — Government policy — Alberta. 4. Energy development — Law and legislation — Alberta. 5. Energy industries — Law and legislation — Alberta. i. Alberta. Energy Resources Conservation Board. ii. Title. iii. Title: 75 years of Alberta energy regulation. iv. Title: Seventy-five years of Alberta energy regulation. hd9574 c23 a4 j37 2013 354.4’528097123 c2013-980015-8 con t e nt s one Mandate 1 two Conservation 23 three Safety 57 four Environment 77 five Peacemaker 97 six Mentor 125 epilogue Born Again, Bigger 147 appendices Chairs 154 Chronology 157 Statistics 173 INSPIRING BEGINNING Rocky Mountain vistas provided a dramatic setting for Alberta’s first oil well in 1902, at Cameron Creek, 220 kilometres south of Calgary. -

Councillor Biographies

BIOGRAPHIES OF COUNCIL MEMBERS The following biographies were complied from the vast information found at the City of Edmonton Archives. Please feel free to contact the Office of the City Clerk or the City of Edmonton Archives if you have more information regarding any of the people mentioned in the following pages. The sources used for each of the biographies are found at the end of each individual summary. Please note that photos and additional biographies of these Mayors, Aldermen and Councillors are available on the Edmonton Public Library website at: http://www.epl.ca/edmonton-history/edmonton-elections/biographies-mayors-and- councillors?id=K A B C D E F G H I, J, K L M N, O P Q, R S T U, V, W, X, Y, Z Please select the first letter of the last name to look up a member of Council. ABBOTT, PERCY W. Alderman, 1920-1921 Born on April 29, 1882 in Lucan, Ontario where he was educated. Left Lucan at 17 and relocated to Stony Plain, Alberta where he taught school from 1901 to 1902. He then joined the law firm of Taylor and Boyle and in 1909 was admitted to the bar. He was on the Board of Trade and was a member of the Library Board for two years. He married Margaret McIntyre in 1908. They had three daughters. He died at the age of 60. Source: Edmonton Bulletin, Nov. 9, 1942 - City of Edmonton Archives ADAIR, JOSEPH W. Alderman, 1921-1924 Born in 1877 in Glasgow. Came to Canada in 1899 and worked on newspapers in Toronto and Winnipeg. -

Writing Alberta POD EPDF.Indd

WRITING ALBERTA: Aberta Building on a Literary Identity Edited by George Melnyk and Donna Coates ISBN 978-1-55238-891-4 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission. If you want to reuse or distribute the work, you must inform its new audience of the licence terms of this work. -

Who Is Really Paying for Your Parking Space?

The University of Alberta Department of Economics WHO IS REALLY PAYING FOR YOUR PARKING SPACE? ESTIMATING THE MARGINAL IMPLICIT VALUE OF OFF-STREET PARKING SPACES FOR CONDOMINIUMS IN CENTRAL EDMONTON, CANADA By OWEN JUNG A Directed Research Project Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Economics Edmonton, Alberta 2009 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I have many people to thank for making this paper possible. First of all, I am indebted to my supervisors, Professor Robin Lindsey and Professor Melville McMillan, for their invaluable comments and suggestions. I would also like to thank Professor David Ryan for providing additional econometric advice. For their patience and support, I wish to thank Professor Denise Young and Audrey Jackson. Special thanks go out to Jon Hall of the REALTORS Association of Edmonton (Edmonton Real Estate Board) for providing the Multiple Listing Service data set employed in this paper. I am also very grateful to Scott Williamson at the University of Alberta, Department of Biological Sciences, for providing ArcView/GIS data, and to Chuck Humphrey at the University of Alberta, Data Library, for compiling and organizing Statistics Canada census data. In addition, I am indebted to Colton Kirsop, Diana Sargent, and Bonny Bellward at the City of Edmonton, Planning and Development Department, for sharing useful parking information. I also acknowledge the assistance received from Larry Westergard and Mary Anne Brenan at the RE/MAX Real Estate Millwoods office in Edmonton. Last, but certainly not least, I want to thank my family and friends for their unconditional love and encouragement. -

Socialists, Populists, Policies and the Economic Development of Alberta and Saskatchewan

Mostly Harmless: Socialists, Populists, Policies and the Economic Development of Alberta and Saskatchewan Herb Emery R.D. Kneebone Department of Economics University of Calgary This Paper has been prepared for the Canadian Network for Economic History Meetings: The Future of Economic History, to be held at Guelph, Ontario, October 17-19, 2003. Please do not cite without permission of the authors. 1 “The CCF-NDP has been a curse on the province of Saskatchewan and have unquestionably retarded our economic development, for which our grandchildren will pay.”(Colin Thatcher, former Saskatchewan MLA, cited in MacKinnon 2003) In 1905 Wilfrid Laurier’s government established the provinces of Saskatchewan and Alberta with a border running from north to south and drawn so as to create two provinces approximately equal in area, population and economy. Over time, the political boundary has defined two increasingly unequal economies as Alberta now has three times the population of Saskatchewan and a GDP 4.5 times that of Saskatchewan. What role has the border played in determining the divergent outcomes of the two provincial economies? Factor endowments may have made it inevitable that Alberta would prosper relative to Saskatchewan. But for small open economies depending on external sources of capital to produce natural resources for export, government policies can play a role in encouraging or discouraging investment in the economy, especially those introduced early in the development process and in economic activities where profits are higher when production is spatially concentrated (agglomeration economies). Tax policies and regulations can encourage or discourage location decisions and in this way give spark to (or extinguish) agglomeration economies. -

Lynnwood Townhome Site 8721/8725/8731/8735 - 150 Street

Site Lynnwood Shopping Centre 87 Avenue 149 street Lynnwood Townhome Site 8721/8725/8731/8735 - 150 Street > 18,273 SF of townhome zoned land located just off 149 Street Asking Price: > Situated to allow for convenient access to numerous West Edmonton amenities such as: Lynnwood Shopping Centre, Meadowlark Shopping Centre, and West Edmonton Mall $1,295,000 > Ease of access to the downtown core, and south Edmonton (Via Whitemud Drive) ($82/SF) > Site is currently zoned for DC2 allowing for 9 townhomes and 9 accessory suites. (18 suites total) > Lynnwood and surrounding neighborhoods have become some of the most desirable infill neighborhoods in Edmonton Current Allowable Accessory DC2 Zoning 9 Units +9 Units AMIT GROVER JANDIP DEOL BRANDON IMADA Vice President Associate Vice President Associate 780 969 3006 780 969 3043 780 969 3019 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Site 87 avenue 149 street Specifications Easy A0ccess to Downtown Civic Address 8721/8725/8731/8735 - 150 Street The Property is located just north of 87th Avenue and east of 150th Street in the gentrifying Lynwood neighborhood. Situated Legal Plan Plan 5572HW, Block 1, Lot 15-18 just off of 149th Street, this location provides ease of access to virtually every amenity. 149 Street acts as the primary point of Neighbourhood Lynnwood access to Stony Plain Road and downtown Edmonton. It also al- Zoning DC2 (Direct Control) lows access to the Whitemud freeway, leading to the southside Edmonton, Anthony Henday Drive, and west-end suburban neigh- Allowable Units 9 Townhome Units & 9 Accessory Units borhoods. -

Muscular Christian Edmonton: the Story of the Edmonton Young Men’S Christian Association 1898-1920

MUSCULAR CHRISTIAN EDMONTON: THE STORY OF THE EDMONTON YOUNG MEN’S CHRISTIAN ASSOCIATION 1898-1920 Monograph by Courtney van Waas Graduate Program in Kinesiology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Sport History The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Courtney van Waas 2015 Abstract From its initial conception as the EYMI in 1898 to its emergence as the Edmonton YMCA through 1920, the institution always had a distinct purpose. The absence of a Muscular Christian agenda in the EYMI, coupled with a purposive refocusing of programming within the YMCA towards what was directed towards the public interest, religion within this institution waned following World War I. Newspapers and executive minute notes demonstrate the EYMI focus on producing the next generation of respectable businessmen. The Edmonton YMCA attempted to fulfill the task of ‘saving’ young men by distracting them from social vices. As a result of the far-reaching social influences of the First World War, the YMCA significantly turned away from its religious practices. Indeed, the YMCA shifted emphasis from its religious-oriented Muscular Christian emphasis towards providing more secular, athletic programs and services to its members. Keywords Edmonton Young Men’s Institute (EYMI), Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), Edmonton Bulletin Newspaper, Executives EYMI and YMCA Minutes Books, Muscular Christianity ii Acknowledgments For Elijah Paul van Waas The man who showed me true Muscular Christianity A special thank-you to Henk and Sylvia van Waas For your tireless reading and helpful suggestions Candace and Ryan Kraushaar For your encouragement to take a Masters in the first place And my supervisor Dr. -

Student Research Digital Resource List

Student Research Digital Resource List The purpose of this document is to 1) help you choose a Heritage Fair topic and 2) help you find source material to research your topic. We have provided resources related to the Edmonton area, Alberta & Canada. What is a Primary Source? ● A primary source is a work that gives original information. ● A primary source is something created during a time being studied or from a person who was involved in the events being studied. ● Examples of primary sources are letters, newspapers, a diary, photographs, maps, speeches, memories, etc. What is a Secondary Source? ● A secondary source is a document or recording that writes or speaks about information that is one step removed from the original source. ● Secondary sources interpret, evaluate or discuss information found in primary sources. ● Examples of secondary sources include academic articles, biographies, text books, dictionaries, most books, encyclopedias, etc. Edmonton Resources Brief History of the Papaschase Band as recorded in the Papaschase First Nation Statement of Claim. https://www.papaschase.ca/text/papaschase_history.pdf City of Edmonton Archives- Digital Catalogue Great resource for historical images and primary sources.https://cityarchives.edmonton.ca/ 1 City of Edmonton Archives- Online Exhibits The City of Edmonton Archives' virtual exhibits draw upon the records held at the Archives to tell stories about our city and our history. City of Edmonton History of Chinatown report https://www.edmonton.ca/documents/PDF/HistoryofChinatown%20(2).pdf Edmonton & Area Land Trust https://www.ealt.ca/ The Edmonton and Area Land Trust works to protect natural areas to benefit wildlife and people, and to conserve biodiversity and all nature’s values, for everyone forever. -

Annotated Bibliography of the Cultural History of the German-Speaking Community in Alberta: 1882-2000

Annotated Bibliography of the Cultural History of the German-speaking Community in Alberta Fifth Up-Date: 2008-2009 A project of the German-Canadian Association of Alberta © 2010 Compiler: Manfred Prokop Annotated Bibliography of the Cultural History of the German-speaking Community in Alberta: 1882-2000. Fifth Up-Date: 2008-2009 In collaboration with the German-Canadian Association of Alberta German-Canadian Cultural Center, 8310 Roper Road, Edmonton, AB, Canada T6E 6E3 Compiler: Manfred Prokop 209 Tucker Boulevard, Okotoks, AB, Canada T1S 2K1 Phone/Fax: (403) 995-0321. E-Mail: [email protected] ISBN 0-9687876-0-6 © Manfred Prokop 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Overview ............................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Quickstart ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Description of the Database ............................................................................................................................................... 2 Brief history of the project .................................................................................................................................... 2 Materials ................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Sources ...................................................................................................................................................................