Pioneer Bishop, Pioneer Times: Nykyta Budka in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Belgian Catholic Relations with “Others” in Western Canada, 1880-1940

Belgian Catholic Relations with “Others” in Western Canada, 1880-1940 CORNELIUS J. JAENEN University of Ottawa Belgians arrived in western Canada when the Catholic hierarchy was largely francophone, identified with selective immigration and an ideology of agriculturalism. Francophone Catholics were the dominant European element in the west in the fur trade and initial settlement periods. Following the Red River resistance movement and the creation of the province of Manitoba in 1870, the Catholic Church sought to retain its prominent role through the repatriation of Franco-Americans and the recruitment of francophone European Catholic agricultural settlers. This immigration effort extended to Belgium, perceived as an orthodox Catholic realm, populated by two ethnic groups – Walloons and Flemings – and the home of the Séminaire Anglo-Belge of Bruges and the American College of the University of Louvain that trained clergy specifically for North America. The resulting emigration did not always correspond to the clerical vision in the Canadian west. The majority of early French-speaking Walloon immigrants, for example, were more often involved in coal mining than farming and their religious views and practices usually were controversial. On the other hand, the Flemish-speakers were interested in taking up homesteads, or establishing themselves as dairy farmers near St. Boniface/Winnipeg. These Flemings were conservative Catholics, a number who also spoke French, but they were not the first choice of the colonizing clergy who wanted francophones. The immigration agents who worked with the clergy were interested in maintaining a francophone Historical Papers 2007: Canadian Society of Church History 18 Belgian Catholic Relations with “Others” in Western Canada Catholic balance with the incoming anglophone settlers from Ontario and immigrants such as the Icelanders, Mennonites and Doukhobors. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1984

Vol. Ul No. 38 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 16,1984 25 cents House committee sets hearings for Faithful mourn Patriarch Josyf famine study bill WASHINGTON - The House Sub committee on International Operations has set October 3 as the date for hearings on H.R. 4459, the bill that would establish a congressional com mission to investigate the Great Famine in Ukraine (1932-33), reported the Newark-based Americans for Human Rights in Ukraine. The hearings will be held at 2 p.m. in Room 2200 in the Sam Rayburn House Office Building. The chairman of the subcommittee, which is part of the Foreign Affairs Committee, is Rep. Dan Mica (D-Fla.). The bill, which calls for the formation of a 21-member investigative commission to study the famine, which killed an esUmated ^7.^ million UkrdtftUllk. yif ітіІДЯДІШ'' House last year by Rep. James Florio (D-N.J.). The Senate version of the measure, S. 2456, is currently in the Foreign Rela tions Committee, which held hearings on the bill on August I. The committee is expected to rule on the measure this month. In the House. H.R. 4459 has been in the Subcommittee on International Operations and the Subcommittee on Europe and the Middle East since last November. According to AHRU, which has lobbied extensively on behalf of the legislation, since one subcommittee has Marta Kolomaysls scheduled hearings, the other, as has St. George Ukrainian Catholic Church in New Yoric City and parish priests the Revs, Leo Goldade and Taras become custom, will most likely waive was but one of the many Ulcrainian Catholic churches Prokopiw served a panakhyda after a liturgy at St. -

Two of Edmonton's Soc'a Residential Schools Healing and Rec- Planning Council's 2001 Award of Onciliation Issues

Maggie is currently working on Marjorie received Edmonton Social Two Of Edmonton's Soc'a residential schools healing and rec- Planning Council's 2001 Award of onciliation issues. Her work serves Recognition and in 2003, she re- Activists Honoured to support the Alternative Dispute ceived the Distinguished Alumni Resolution process to resolve cases Award from Grant MacEwan Com- Order Of Canada outside of court. munity College. She is a wife, mother, grandmother On February 3, 2006 Marjorie was and an auntie who has helped raise appointed a Member of the Order COLLEEN CHAPMAN other children. And this writer can of Canada in the category of Social Edmonton has recently been blessed attest to the fact that she is a fiercely Science, Marjorie also received the friend. with the honouring of two of the loyal Maggie values building Alberta Centennial Medal for out- City's most tireless workers in the relationships in families of com- standing achievements and contri- category of Social Sciences. Two munities within the limits of our butions to the community. women, well known in city circles, humanity and with the Creator's have been named to the Order of guiding hand. Marjoie says she is "humbled" by Canada: Dr. Maggie Hodgson, this honour, but she mostly wanted named as an Officer of the Order of to talk about the Food Bank. This Canada, and Marjorie Bencz, named year marks the twenty-fift- h year of as Member of the Order of Canada. its existence and, quite frankly, Mar- jorie would vastly prefer to work Dr. Maggie Hodgson is a member of r herself out of a job. -

1 2/5/2018, 4:45 Pm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Oleskiw 1 2/5/2018, 4:45 PM Dr. Joseph Oleskiw or Jósef Olesków ([Іосифъ Олеськôвъ (historic spelling),[1] Осип Олеськів (modern spelling), Osyp Oleskiv] error: {{lang- xx}}: text has italic markup (help), September 28, 1860 – October 18, 1903) was a Ukrainian professor of agronomy who promoted Ukrainian immigration to the Canadian prairies. His efforts helped encourage the initial wave of settlers which began the Ukrainian Canadian community. Ukraine Early immigration The journey Canada Immigration to Canada begins Later life Bust of Joseph Oleskiw at the Ukrainian Legacy Cultural Heritage Village in Alberta, Canada See also References Bibliography External links Joseph Oleskiw was born in the village of Nova Skvariava (Nowa Skwarzawa), near Zhovkva, in the Austro-Hungarian province of Galicia (now western Ukraine.) His father, a Greek (Eastern) Catholic parish priest, was a member of the rural élite. Oleskiw studied geography and agriculture at the University of Lemberg (Lviv, Ukraine). He was appointed professor of agronomy at the teacher’s college in Lemberg.[2] Ukrainian immigrants who had traveled to Brazil and Argentina, enticed by the free transportation they had received, sent back word that conditions there were worse than in their homeland. After hearing of the struggles of Ukrainian immigrants in Joseph Oleskiw (1860–1903) Brazil, Oleskiw investigated alternative choices. He determined that the Canadian prairies were the most suitable for the Ukrainian farmers. This led to Oleskiw writing two pamphlets in Ukrainian – "On Free Lands" (Pro Vilni Zemli,[1][3] spring 1895), and "On Emigration" (O https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Oleskiw 1 of 4 2/5/2018, 4:45 PM https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Oleskiw 2 2/5/2018, 4:45 PM emigratsiy,[4] December 1895) – and one in Polish. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1977, No.32

www.ukrweekly.com І СВОБОДАХSvOBODA І І Ж Щ УКРАЇНСЬКИЙ ЩОДЕННИК ЧЩЕ? UKRAINIAN DAiLy Щ Щ UkrainiaENGLISH LANGUAGnE WEEKL Y WeekEDITION !У VOL. LXXXIV No. 187 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, AUGUST 28,1977 25 CENTS Dedicate Bust of Rev. Dmytriw Dr. Shtern Expected to Attend in Tribute to Ukrainian Pioneers New York Rally September 18th Ceremony Caps UNA Program NEW YORK, N.Y.—The UCCA Dr. Shtern was allowed to leave the executive office here has sent an Soviet Union with his wife. invitation to Dr. Mikhail Shtern, a Dr. Shtern is known for his de– During Dauphin Festival former Ukrainian political prisoner, fense of the Ukrainian culture . to attend the rally in defense of During the trial, he refused to speak Ukrainian rights here Sunday, Sep– in any other language, except Ukrai– tember 18. nian. A spokesman for the office said After settling in Paris, France, Dr. that the 62-year-old doctor has Shtern wrote in the July 2nd edition accepted the invitation to attend. of the Ukrainian newspaper "Nash Dr. Shtern, who is of Jewish Holos" (Our World) this year that he descent, was a physician in the town believes that Ukraine will someday of vynnytsia in western Ukraine. On be free. May 29, 1974, Dr. Shtern was arres– "You can be sure that Russifica– ted after his son, August, received tion will not devour the Ukrainian permission to emigrate to israel. nation. And also be sure that Uk– The KGB interrogated many wit– raine will be a free and fortunate nesses from Dr. Shtern's home town, state. -

Lamont County

Church Capital of North America LAMONT COUNTY The strange new world did not deter them To build a church they could ill afford Their way of life was not complete Without an edifice to the Lord. Welcome to LAMONT COUNTY’S SELF-GUIDED CHURCH TOURS Lamont County has 47 churches— more per capita than anywhere else in North America. Lamont County has a proud legacy as the birthplace of the oldest and largest agricultural settlement of Ukrainians in Canada. The nucleus of the pioneer Ukrainian colony was in the vicinity of Star, some seven miles (11.6 km) north- east of the modern-day town of Lamont. There, in 1894, four immigrant families filed for adjacent homesteads at what became the centre of a thriving bloc settlement that eventually encompassed the region that now comprises the Kalyna Country Ecomuseum. Not surprisingly, the historic Star district was also the site where organized Christian life first took root among the Ukrainians of Alberta, about the same time that the sod huts originally put up as temporary shelters by the pioneers began to be replaced by modest, thatched-roofed houses. As more and more newcomers from Europe made East Central Alberta their home, Lamont County experienced a remarkable church-building boom expressive of the deep Christian faith brought over from the Old World by the set- tlers. This rich spiritual heritage is still very much in evi- dence today, in the numerous churches that can be found in the towns and villages and on country roads in virtually every part of the municipality. -

Athanasius D. Mcvay. God's Martyr, History's Witness

Book Reviews 193 Athanasius D. McVay. God’s Martyr, History’s Witness: Blessed Nykyta Budka, the First Ukrainian Catholic Bishop of Canada. Edmonton: Ukrainian Catholic Eparchy of Edmonton and the Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky Institute of Eastern Christian Studies, 2014. xxvi, 613 pp. Illustrations. Timeline. Bibliography. Index. C$25.00, paper. he book by Athanasius D. McVay is quite remarkable. It gives a T comprehensive account of the life and work of Nykyta Budka, the first Ukrainian Catholic bishop in Canada. At the same time, it provides more than just the biography of a person, however illustrious; it historicizes a troublesome epoch ranging from the beginning to the middle of the twentieth century and covers different milieux—Austria-Hungary, Poland, Ukraine, Canada, the United States, and the Soviet Union. It is a tremendous task to weave a large “cloth” with a temporal warp and geographic weft, and it is especially difficult if one has to use thousands of “threads” of varying colours and thicknesses. However, the author has managed to realize what seems only possible as metaphor. He has woven together thousands of details and facts about Bishop Budka, his place and time, and has created an epic, and yet entertaining, story. Even if one is not particularly interested in the main character of the story, the book is worth reading because it describes with precision the many sides of life of the Ukrainian Catholic community in various places and circumstances. In order to assemble his story, the author searched through many archives, -

Ofreligion in Ne

SOVIET PERSECUTION OFRELIGION IN NE SOVIET PERSECT.JTION OFRETIGION IN NE WORLD CONGRESS OF FREE UKRAINIANS TORONTO CANADA 1976 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION AND ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THIS BROCHURE, WRITE TO: HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION WORLD CONGRESS OF FREE UKRAINIANS SUITE 2 2395ABLOOR STREET WEST TORONTO, ONTARIO M6S IP6 CANADA Printed by HARMONY PRINTING tTD. 3194 Dundos St.W., Toronto, Ont., Conodo, M6P 2A3 FOREWORD This brochure deals with the persecution ol religion and, reli- gious belieuers in Souiet Ukraine. It documents uiolations ol the lundamental human right to lreedom ol conscience, aiolations which contradict the international accords relating to human rights to uthich the Souiet Union is a sign'atory. The present publication is part ol the international efforts, ini- tiated in 1976 by the World Congress ol Free Ukrainians, in delence of religion in Sooiet Ukraine. The purpose ol this boolelet, and the campaign in general, is to inlorm international public opinion about the plight ol belieaers in Uhraine and to encourage it to speak out against these uiolations ol international legality. Without the sus- tained, pressure ol world public opinion it can hardly be hoped that protests ol persecuted belieuers will be heard by the Souiet gouern- ment, or that it would, effectiuely enlorce the constitutional and, international gwarantees ol lreedom ol conscience in Souiet Ukraine. In particular, we are asking all men and u)on'Len ol good will to join with us in demanding that the Soaiet authorities release all clergy, monastics and, belieaers imprisoned lor their religious prac- tices and beliefs; that the Souiet gouerwnent remoue the illegal and unjust prohibition ol the Ukrainian Greele Catholic Church, the Ukrainian Autoceph,alous Orthodox Church and some other religious denominations in the Ukrainian SSR; and that it return the child,ren tahen lrorn their parents because ol the latter's raising them in ac- cordance with their religious beliefs. -

Ukrainian Canadian Content in the Newspaper Svoboda 1893–1904

Research Report No. 7 UKRAINIAN CANADIAN CONTENT IN THE NEWSPAPER SVOBODA 1893-1904 Compiled by Frances A. Swyripa and Andrij Makuch Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies The University of Alberta Edmonton 1985 Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies University of Alberta Occasional Research Reports Editorial Board Andrij J. Hornjatkevy6 (Humanities) Bohdan Krawchenko (Social Sciences) Manoly R. Lupul (Ukrainians in Canada) Myroslav Yurkevich (History) The Institute publishes research reports, including theses, periodically. Copies may be ordered from the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, 352 Athabasca Hall, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, T6G 2E8. The name of the publication series and the substantive material in each issue (unless otherwise noted) are copyrighted by the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies. Occasional Research Reports UKRAINIAN CANADIAN CONTENT IN THE NEWSPAPER SVOBODA 1893 - 1904 Compiled by Frances A. Swyripa and Andrij Makuch Research Report No. 7 — 1985 Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies University of Alberta Edmonton, Alberta TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 5 Transliteration 7 Entries by Date 9 1893 9 1894 10 1895 13 1896 16 1897 22 1898 30 1899 36 1900 43 1901 48 1902 59 1903 72 1904 86 Index 97 INTRODUCTION Until the inauguration of Kanadyiskyi farmer (Canadian Farmer) in November 1903, the American Ukrainian newspaper, Svoboda (Liberty), constituted the sole forum for the exchange of information, ideas and experiences among Ukrainians in widely scattered communities in Canada. As a result, Svoboda is one of the major sources on early Ukrainian Canadian life available to historical researchers. The following annotated index of Ukrainian Canadian content in Svoboda for the years 1893-1904 is, with few exceptions, comprehensive. -

Parishioners of St. Nicholas Church. Source

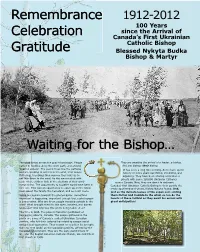

Remembrance 1912-2012 100 Years since the Arrival of Celebration Canada’s First Ukrainian Catholic Bishop Gratitude Blessed Nykyta Budka Bishop & Martyr Waiting for the Bishop… Source: Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa Canada, Archives Library and Source: The wind blows across the prairie landscape. People They are awaiting the arrival of a leader…a bishop. gather in huddles along the worn path, and around Not any bishop; their bishop. ‘quaking aspens’. The young trees line the pathway It has been a long time coming. Some have spent and are bending to and fro in the wind, their leaves twenty or more years sacrificing, struggling, and fluttering…trembling. Men remove their hats as to adjusting. They have been sharing a handful of not lose them to the wind. As the women chat with priests with some 150,000 Ukrainian Catholics each other, children hide in the shadows of their wind- across Canada. Now, they are about to welcome swept skirts. The opportunity to socialize would have been a Canada’s first Ukrainian Catholic Bishop to their parish; the rare one. This was an opportunity to catch up on the latest newly appointed and young, Bishop Nykyta Budka. And, news about the family, the homeland, and so much more. just as the delicate leaves of the aspen surrounding Some are looking towards the photographer. Something them flutter and tremble in the wind, so too do the important is happening; important enough that a photograph hearts of these faithful as they await his arrival with is being taken. Why are these people standing outside in the great anticipation! wind? What brought them to this open, isolated, and barren landscape? And why was this photo being taken at all? The time is 1916. -

Blessed Bishop Martyr Nykyta Budka the First Bishop of the Ukrainian Catholics in Canada

Blessed Bishop Martyr Nykyta Budka The First Bishop of the Ukrainian Catholics in Canada О мій Боже, з глибини моєї душі клонюся перед Твоєю безмежною Величчю. Дякую Тобі за ласки й дари, що ними Ти наділив Твого вірного Слугу Блаженного Мученика Єпископа Никиту. Прошу Тебе, прослав його також славою святого. Благаю Тебе, через його посередництво, уділи мені в своєму Батьківському милосердю ту ласку (намірення), про яку я Тебе покірно молю. Амінь. The first bishop the Ukrainian Catholic Church in Canada was born on September 7, 1877 Dobomirka, Zbarazh District, Ukraine and arrived in Canada on December 19, 1912. On December 22, his investure was held in St. Nicholas Church in the presence of approximately 2000 spiritually uplifted faithful. The bishop initially resided in the Basilian rectory. In January, 1913, a home was purchased for the bishop’s residence to which he moved in March of that year. The tasks for the first bishop were monumental as his diocese stretched from the Pacific to the Atlantic Oceans and encompassed approximately 150 000 Ukrainians and approximately 80 churches and chapels. Initially there were 13 secular priests and 9 monks, including the bishop’s secretary, Rev. Joseph Bala, who accompanied him to Canada, assisting in the service of this wide expanse of faithful and organized communities. The bishop’s work focused mainly on visiting the faithful and organizing new parish communities. Bishop Budka worked hard on the Incorporation Act to legally safeguard church property and wealth which before his arrival was often the cause of misunderstandings and even led to divisions within parishes. -

UNWLA Holds 25Th Convention Ukrainian Troops Not Yet Ready To

INSIDE:• Vienna conference focuses on nuclear safety in East bloc — page 2. • New visa procedures issued by U.S. Embassy in Kyiv — page 7. • What’s on the air, new releases, book reviews — pages 8-9. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXVII HE KRAINIANNo. 26 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JUNE 27, 1999 EEKLY$1.25/$2 in Ukraine TrilateralT cooperative programU aims to strengthen Ukrainian troopsW not yet ready Ukraine’s market economy and civil society to serve as peacekeepers in Kosovo by Roman Woronowycz The program, supported by a $2 million by Roman Woronowycz Although Ukraine has participated Kyiv Press Bureau grant from the United States through its Kyiv Press Bureau actively in the United Nations peacekeeping Agency for International Development, efforts in Bosnia and announced that it was KYIV – The United States Embassy on which will be managed by the Eurasia KYIV – Ukrainian soldiers will join their ready to organize such a force for Kosovo June 11 announced a cooperative program Foundation, calls for financing projects to NATO and Russian counterparts in a even in the first days of the air campaign between Ukraine, Poland and the United be proposed by higher educational institu- Kosovo peacekeeping force only after the against rump Yugoslavia, the country has States to strengthen Ukraine’s market econ- tions, local governments and state institu- proposed plan for Ukrainian involvement been slow to approve a peacekeeping con- omy and civil society. tions. Three areas of reform are being winds its way through the bureaucratic tingent for Kosovo.