Ossenbach Et Pupulin Rich Coast.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Valley & Highlands

© Lonely Planet Publications 124 lonelyplanet.com ALAJUELA & THE NORTH OF THE VALLEY 125 History exhibit, trout lake and the world’s largest butterfly Central Valley & Of the 20 or so tribes that inhabited pre- enclosure. Hispanic Costa Rica, it is thought that the Monumento National Arqueológico Guayabo Central Valley Huetar Indians were the most ( p160 ) The country’s only significant archaeological site Highlands dominant. But there is very little historical isn’t quite as impressive as anything found in Mexico or evidence from this period, save for the ar- Guatemala, but the rickety outline of forest-encompassed cheological site at Guayabo. Tropical rains villages will still spark your inner Indiana Jones. Parque Nacional Tapantí-Macizo Cerro de la The rolling verdant valleys of Costa Rica’s midlands have traditionally only been witnessed and ruthless colonization have erased most of pre-Columbian Costa Rica from the pages Muerte ( p155 ) This park receives more rainfall than during travelers’ pit stops on their way to the country’s more established destinations. The of history. any other part of the country, so it is full of life. Jaguars, area has always been famous for being one of the globe’s major coffee-growing regions, In 1561 the Spanish pitched their first ocelots and tapirs are some of the more exciting species. CENTRAL VALLEY & and every journey involves twisting and turning through lush swooping terrain with infinite permanent settlement at Garcimuñoz, in Parque Nacional Volcán Irazú ( p151 ) One of the few lookouts on earth that affords views of both the Caribbean HIGHLANDS coffee fields on either side. -

Distritos Declarados Zona Catastrada.Xlsx

Distritos de Zona Catastrada "zona 1" 1-San José 2-Alajuela3-Cartago 4-Heredia 5-Guanacaste 6-Puntarenas 7-Limón 104-PURISCAL 202-SAN RAMON 301-Cartago 304-Jiménez 401-Heredia 405-San Rafael 501-Liberia 508-Tilarán 601-Puntarenas 705- Matina 10409-CHIRES 20212-ZAPOTAL 30101-ORIENTAL 30401-JUAN VIÑAS 40101-HEREDIA 40501-SAN RAFAEL 50104-NACASCOLO 50801-TILARAN 60101-PUNTARENAS 70501-MATINA 10407-DESAMPARADITOS 203-Grecia 30102-OCCIDENTAL 30402-TUCURRIQUE 40102-MERCEDES 40502-SAN JOSECITO 502-Nicoya 50802-QUEBRADA GRANDE 60102-PITAHAYA 703-Siquirres 106-Aserri 20301-GRECIA 30103-CARMEN 30403-PEJIBAYE 40104-ULLOA 40503-SANTIAGO 50202-MANSIÓN 50803-TRONADORA 60103-CHOMES 70302-PACUARITO 10606-MONTERREY 20302-SAN ISIDRO 30104-SAN NICOLÁS 306-Alvarado 402-Barva 40504-ÁNGELES 50203-SAN ANTONIO 50804-SANTA ROSA 60106-MANZANILLO 70307-REVENTAZON 118-Curridabat 20303-SAN JOSE 30105-AGUACALIENTE O SAN FRANCISCO 30601-PACAYAS 40201-BARVA 40505-CONCEPCIÓN 50204-QUEBRADA HONDA 50805-LIBANO 60107-GUACIMAL 704-Talamanca 11803-SANCHEZ 20304-SAN ROQUE 30106-GUADALUPE O ARENILLA 30602-CERVANTES 40202-SAN PEDRO 406-San Isidro 50205-SÁMARA 50806-TIERRAS MORENAS 60108-BARRANCA 70401-BRATSI 11801-CURRIDABAT 20305-TACARES 30107-CORRALILLO 30603-CAPELLADES 40203-SAN PABLO 40601-SAN ISIDRO 50207-BELÉN DE NOSARITA 50807-ARENAL 60109-MONTE VERDE 70404-TELIRE 107-Mora 20307-PUENTE DE PIEDRA 30108-TIERRA BLANCA 305-TURRIALBA 40204-SAN ROQUE 40602-SAN JOSÉ 503-Santa Cruz 509-Nandayure 60112-CHACARITA 10704-PIEDRAS NEGRAS 20308-BOLIVAR 30109-DULCE NOMBRE 30512-CHIRRIPO -

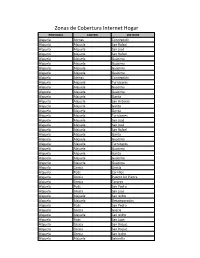

Zonas De Cobertura Internet Hogar

Zonas de Cobertura Internet Hogar PROVINCIA CANTON DISTRITO Alajuela Atenas Concepción Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Atenas Concepción Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela San Antonio Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San José Alajuela Alajuela San Rafael Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Turrúcares Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Garita Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Alajuela Guácima Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Poás Carrillos Alajuela Grecia Puente De Piedra Alajuela Grecia Tacares Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia San José Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Desamparados Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Poás San Juan Alajuela Grecia San Roque Alajuela Grecia San Roque Alajuela Grecia San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Sabanilla Alajuela Alajuela Tambor Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Carrizal Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Alajuela Carrizal Alajuela Alajuela Tambor Alajuela Grecia Bolivar Alajuela Grecia Grecia Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Grecia San Jose Alajuela Alajuela San Isidro Alajuela Grecia Tacares Alajuela Poás San Pedro Alajuela Grecia Tacares -

Agua Caliente, Espacialidad Y Arquitectura En Una Comunidad Nucleada Antigua De Costa Rica

31 Cuadernos de Antropología No.19, 31-55, 2009 AGUA CALIENTE, ESPACIALIDAD Y ARQUITECTURA EN UNA COMUNIDAD NUCLEADA ANTIGUA DE COSTA RICA Jeffrey Peytrequín Gómez* RESUMEN En este artículo se presentan las particularidades de un sitio arqueológi- co ubicado en el Valle Central Oriental de Costa Rica, Agua Caliente de Cartago (C-35AC). Alrededor del 600 d.C., esta comunidad se constituyó en un centro político-ideológico con un ordenamiento espacial que permitió el despliegue de diversas actividades; dichas actividades son el reflejo de relaciones sociales a nivel cacical. En Agua Caliente se erigieron varias es- tructuras habitacionales, así como muros de contención de aguas, calzadas y vastos cementerios. Además, todas estas manifestaciones arquitectónicas comparten un tipo de construcción específico. De tal manera, la cultura material recuperada apunta a Agua Caliente como un espacio significativo dentro de la dinámica cultural de esta región de Costa Rica. Palabras claves: Arquitectura, técnicas constructivas, montículos, calza- das, dique. ABSTRACT This article explores the architectural specificities of Agua Caliente de Car- tago (C-35AC), an archaeological site located in the Costa Rica’s central area. This community, circa 600 A.D., was an ideological-political center with a spatial distribution that permitted diverse activities to take place. These practices reflect rank social relations at a chiefdom level. Several dwelling structures were at Agua Caliente, as were stone wall dams, paved streets and huge cemeteries. These constructions shared particular charac- teristics. The material culture suggests that this site was a significant space in the regional culture. Keywords: Architecture, building techniques, mounds, causeways, dam. * Jeffrey Peytrequín Gómez. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

2551-0730, 2592-2097, Ext.: 102

Municipalidad de Oreamuno 1 Alcaldía Municipal Telefax: 2551-0730, 2592-2097, ext.: 102. MUNICIPALIDAD DE OREAMUNO LICITACIÓN ABREVIADA Nº2018LA-000009-01, MANTENIMIENTO, MEJORAMIENTO, REHABILITACIÓN DE SUPERFICIE DE RUEDO Y CANALIZACIÓN DE AGUAS PLUVIALES DE LAS CALLES Y CAMINOS DE LOS DISTRITOS DE SANTA ROSA, CIPRESES, POTRERO CERRADO Y COT DEL CANTÓN DE OREAMUNO. INVITACION La Municipalidad de Oreamuno, ubicada en San Rafael de Oreamuno de Cartago, costado suroeste de la Iglesia Católica, les invita a participar de la Licitación Abreviada Nº2018LA-000009-01, Mantenimiento, Mejoramiento, Rehabilitación de Superficie de Ruedo y Canalización de Aguas Pluviales de las Calles y Caminos de los Distritos de Santa Rosa, Cipreses, Potrero Cerrado y Cot del Cantón de Oreamuno, se recibirán ofertas hasta las 08:00 horas del día 28 de noviembre del 2018. SECCION I CONDICIONES GENERALES 1. OBJETO DEL CONTRATO. Ejecutar actividades de mantenimiento, mejoramiento y rehabilitación en los caminos de los Distritos de Santa Rosa, Cipreses, Potrero Cerrado y Cot. Todo lo anterior de conformidad con los términos, características y especificaciones técnicas descritas en este cartel. 2. DEFINICIÓN DE TÉRMINOS. Cuando en este cartel se refieran a los siguientes términos, deberá entenderse para cada situación los siguientes conceptos: Municipalidad: Municipalidad de Oreamuno. Proveeduría: Departamento encargado de determinar el procedimiento de esta licitación, así como coordinar los procesos administrativos relativos a su trámite. Concejo Municipal: Órgano competente para dictar el acto de adjudicación, conocer y aprobar o improbar las modificaciones de contrato, reajuste de precios, resolver o rescindir el proceso, según corresponda en la ejecución del contrato. Municipalidad de Oreamuno 2 Alcaldía Municipal Telefax: 2551-0730, 2592-2097, ext.: 102. -

Horario Y Mapa De La Ruta CARTAGO

Horario y mapa de la línea CARTAGO - TOBOSI de autobús Terminal Alto De Quebradilla, CARTAGO - TOBOSI Cartago →Terminal Cartago, Ver En Modo Sitio Web Costado Sur Plaza Yglesias La línea CARTAGO - TOBOSI de autobús (Terminal Alto De Quebradilla, Cartago →Terminal Cartago, Costado Sur Plaza Yglesias) tiene 7 rutas. Sus horas de operación los días laborables regulares son: (1) a Terminal Alto De Quebradilla, Cartago →Terminal Cartago, Costado Sur Plaza Yglesias: 5:00 - 7:00 (2) a Terminal Cartago, Costado Sur Plaza Yglesias →Terminal Alto De Quebradilla, Cartago: 18:20 (3) a Terminal Cartago, Costado Sur Plaza Yglesias →Terminal Quebradilla, Frente A Parque Quebradilla: 8:25 - 21:00 (4) a Terminal Cartago, Costado Sur Plaza Yglesias →Terminal Tobosi, Contiguo A Pollos Charlie: 7:10 (5) a Terminal Cartago, Costado Sur Plaza Yglesias →Terminal Tobosi, Frente A Pollos Charlie: 5:30 - 17:50 (6) a Terminal Tobosi, Contiguo A Pollos Charlie →Terminal Cartago, Costado Sur Plaza Yglesias: 5:50 - 20:15 (7) a Terminal Tobosi, Frente A Pollos Charlie →Terminal Cartago, Costado Sur Plaza Yglesias: 4:30 - 17:10 Usa la aplicación Moovit para encontrar la parada de la línea CARTAGO - TOBOSI de autobús más cercana y descubre cuándo llega la próxima línea CARTAGO - TOBOSI de autobús Sentido: Terminal Alto De Quebradilla, Horario de la línea CARTAGO - TOBOSI de autobús Cartago →Terminal Cartago, Costado Sur Plaza Terminal Alto De Quebradilla, Cartago →Terminal Yglesias Cartago, Costado Sur Plaza Yglesias Horario de ruta: 35 paradas lunes 5:00 - 7:00 VER HORARIO DE LA LÍNEA martes 5:00 - 7:00 Terminal Alto De Quebradilla, Cartago miércoles 5:00 - 7:00 Frente A Escuela Alto De Quebradilla, Cartago jueves 5:00 - 7:00 viernes 5:00 - 7:00 Provisional sábado Sin servicio Frente A Bar & Rest. -

1 074-Drpp-2015

074-DRPP-2015.- DEPARTAMENTO DE REGISTRO DE PARTIDOS POLÍTICOS. San José, a las quince horas cinco minutos del veintiséis de junio de dos mil quince. Acreditación de los nombramientos realizados por el partido Acción Ciudadana en los distritos Paraíso y Llanos de Santa Lucía del cantón Paraíso, Tres Ríos y San Rafael del cantón de La Unión, La Suiza y Tayutic del cantón Turrialba, Pacayas y Cervantes del cantón Alvarado y San Isidro y Tobosi del cantón El Guarco de la provincia de Cartago, en virtud de las renuncias de sus titulares. Mediante resoluciones 033-DRPP-2012 de las ocho horas treinta minutos del cinco de octubre de dos mil doce, 043-DRPP-2012 de las trece horas treinta minutos del once de octubre de dos mil doce, 079-DRPP-2012 de fecha dieciséis de noviembre de dos mil doce, 104-DRPP-2012 de las ocho horas veinte minutos del veintiocho de noviembre de dos mil doce y DGRE- 076-DRPP-2013 de las ocho horas treinta y cinco minutos del doce de julio de dos mil trece, se acreditaron las estructuras internas de los distritos antes mencionados. La agrupación política los días veinticinco y veintiséis de abril, celebró las asambleas distritales en los lugares supra citados, con el fin de nombrar los puestos vacantes, esto en virtud de las renuncias de las personas en los distritos mencionados. CANTÓN PARAÍSO Distrito Paraíso: Mediante oficio DRPP-249-2014, de fecha ocho de agosto del dos mil catorce, este Departamento tomó nota de las renuncias presentadas en oficio PAC-CE- 201-2014 de fecha cuatro de agosto de dos mil catorce y recibido en la Ventanilla Única de Recepción de Documentos de la Dirección General del Registro Electoral y Financiamiento de Partidos Políticos el siete de agosto del mismo año, de los señores Edwin Zúñiga Araya, cédula de identidad 303240671, como tesorero suplente y delegado territorial y Asnet Ivannia Quesada Araya, cédula de identidad 303500582 como delegada territorial, acreditados según resolución 033-DRPP-2012. -

Nombre Del Comercio Provincia Distrito Dirección Horario

Nombre del Provincia Distrito Dirección Horario comercio Almacén Agrícola Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Cruce Del L-S 7:00am a 6:00 pm Aguas Claras Higuerón Camino A Rio Negro Comercial El Globo Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, contiguo L - S de 8:00 a.m. a 8:00 al Banco Nacional p.m. Librería Fox Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, frente al L - D de 7:00 a.m. a 8:00 Liceo Aguas Claras p.m. Librería Valverde Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, 500 norte L-D de 7:00 am-8:30 pm de la Escuela Porfirio Ruiz Navarro Minisúper Asecabri Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Las Brisas L - S de 7:00 a.m. a 6:00 400mts este del templo católico p.m. Minisúper Los Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, Cuatro L-D de 6 am-8 pm Amigos Bocas diagonal a la Escuela Puro Verde Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Porvenir L - D de 7:00 a.m. a 8:00 Supermercado 100mts sur del liceo rural El Porvenir p.m. (Upala) Súper Coco Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, 300 mts L - S de 7:00 a.m. a 7:00 norte del Bar Atlántico p.m. MINISUPER RIO Alajuela AGUAS ALAJUELA, UPALA , AGUAS CLARAS, L-S DE 7:00AM A 5:00 PM NIÑO CLARAS CUATRO BOCAS 200M ESTE EL LICEO Abastecedor El Alajuela Aguas Zarcas Alajuela, Aguas Zarcas, 25mts norte del L - D de 8:00 a.m. -

Geology of the Istaru Quadrangle, Costa Rica

Geology of the IstarU Quadrangle, Costa Rica By RICHARD D. KRUSHENSKY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1 3 5 8 Prepared in cooperation with the 0 ficina de Defensa Civil and the Direccion de Geologza, Minas, y Petr6leo, ",..",..:e::~= Ministerio de Industria y Comercio, under the auspices of the Government of Costa Rica and the Agency for International Development, U.S. Department of State A description of the volcanic deposits surrounding Irazu Volcano, and factors involved in slope stability and landslide control UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON 1972 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretm-y GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Directm· Library of Congress catalog-card No. 72-600274 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 -Price $1.70 (paper cover) Stock Number 2401-00263 CONTENTS Page Abstract 1 Introduction 2 Location and accessibility of the area ------------------------ 2 Previous work --------------------------------------------- 3 Purpose and method of investigation -------------------------- 4 Acknowledgments ________________ ·--------------------------- 4 Geologic setting of the Istaru quadrangle ------------------------- 5 Stratigraphy --------------------------------------------------- 6 Tertiary System --------------------------------------------- 6 ~iocene Series ----------------------------------------- 6 Terraha Formation -------------------------------- 6 San Miguel Limestone ------------------------------- 8 Goris -

Aspectos Biofísicos Y Socioeconómicos De La Subcuenca Del Rio Páez, Cartago, Costa Rica

ISSN 1011-484X • e-ISSN 2215-2563 Número 67(2) • Julio-diciembre 2021 Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15359/rgac.67-2.7 Páginas de la 169 a la 193 Recibido: 30/06/2020 • Aceptado: 20/09/2020 URL: www.revistas.una.ac.cr/index.php/geografica/ Aspectos biofísicos y socioeconómicos de la subcuenca del rio Páez, Cartago, Costa Rica Biophysical and socioeconomic aspects of the Páez river sub-basin, Cartago, Costa Rica. María Álvarez-Jiménez1 Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica, Costa Rica Pablo Ramírez-Granados2 Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica, Costa Rica José Castro-Solís3 Universidad Nacional, Costa Rica, Costa Rica Resumen El estudio consistió en una caracterización de variables biofísicas y socioeconómicas de la subcuen- ca del rio Páez, Cartago con el propósito de generar una línea base de la cuenca en el sector norte de Cartago para la toma decisiones por parte de diferentes actores y para proponer lineamientos de manejo de recursos hídricos en un eventual manejo. Se utilizó técnicas de investigación cuantita- tivas y cualitativas entre ellos la aplicación de una encuesta a 178 personas en 10 poblados de la subcuenca distribuidos en la parte alta, media y baja. La subcuenca tiene un área de 28,34 km2, se ubica en los cantones de Oreamuno y Paraíso aproximadamente más del 50% del territorio se de- dica a actividades agropecuarias, un 16% posee cobertura forestal como los usos más importantes, presenta problemáticas importantes de vulnerabilidad, contaminación ambiental, gobernabilidad, 1 MSc. María Álvarez Jiménez. Laboratorio de Hidrogeología y Manejo de Recursos Hídricos. Escuela de Ciencias Ambientales, Universidad Nacional: [email protected]. -

301 Zonashomogeneas Distrito

MAPA DE VALORES DE TERRENOS POR ZONAS HOMOGÉNEAS PROVINCIA 3 CARTAGO CANTÓN 01 CARTAGO DISTRITO 05 AGUACALIENTE O SAN FRANCISCO 506200 511200 516200 521200 a l l i n R e ío r To A y o Mapa de Valores de Terrenos ORIENTAL gr Oreamuno a e i s u OCCIDENTAL q Súper Mas e SAN RAFAEL c A Q GUADALUPE O ARENILLA BARRIO PITAHAYA por Zonas Homogéneas u Antiguo Matadero Municipal e 3 01 05 R03/U03 b Salón comunal r RESIDENCIAL CARTAGO - BARRIO CERRILLOS - SAN LUIS GONZAGA a d R 3 01 05 U04 a ESCUELA PITAHAYA í o Provincia 3 Cartago L MANUEL DE JESUS JIMENEZ u 3 01 05 U02 C æ s 3 01 05 U06 o ia nm r i SANTIAGO s VALLE DEL PRADO - RESIDENCIALnm LAS GARZAS - VEREDAS DEL CONQUISTADOR 3 01 05 U07 Cantón 01 Cartago Avenida 38A CIUDAD DE ORO LLANOS DE SANTA LUCÍA 3 01 05 U27 A 7 o VILLAS DEL SOL - EL CASTILLO r Distrito 05 Aguacaliente o e r l e Teja 3 01 05 U26 l u A a EL TEJAR Cementerio rq C a EscuelaHACIENDA DE ORO HACIENDA REAL B nm ío 3 01 05 U11 3 01 05 U13 San Francisco nm R R 1088400 nm 1088400 COCORI AGUACALIENTE - RESIDENCIAL SAN FRANCISCO í o 3 01 05 U10 nm 3 01 05 U12 JARDINES DE AGUACALIENTE B l a 3 01 05 U24 q u E VALLE VERDE A i A ven TOBOSI A ida 60 l l PARAÍSO T CIUDAD DE LOS NIÑOS 0 o eja LA CAMPIÑA 3 01 05 R14/U14 e r l 3 01 05 U30 3 01 05 R25/U25 l Adepea a 4 enida 6 GUAYABAL Campo de Aterrizaje C Av 3 01 05 U23 nm 2 Presa Q 6 ue Orfanato Salón Comunal b a ra d Hervidero R da i Ruta N n a ciona í G l 231Poblado Barro Morado o ua e v ya A b A a g Llanos de Lourdes FABRICA DE CEMENTO HOLCIM u 3 01 05 R17/U17 a Ministerio de Hacienda C LLANOS DE LOURDES a l i 3 01 05 U16 e n Órgano de Normalización Técnica A San CONDOMINIO EL TEJALæ t Isidro nm e 3 01 05 U29 CACHÍ R BARRO MORADO - NAVARRO ío s C jo 3 01 05 R18/U18 n h ra ir a í N os Guatuso L le al C Cerro Lucosal l Platanillo a j a c s a C a d a r GUATUSO - RIO NAVARRO b to e ri 3 01 05 R19/U19 u r a Q v a N Finca Trinidad ío R Navarrito 1083400 1083400 rro ava Aprobado por: N Q ío Muñeco R u e Iglesia Católica Navarro del Muñeco b r Plaza deæ Deportes a nm d a R o j PEJIBAYE a s Ing.