Did Werner Heisenberg Obstruct German Atomic Bomb Research?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ein Bisher Unbekanntes Zeitzeugnis

N. T. M. 16 (2008) 103–115 0036-6978/08/010103–13 OUND DOI 10.1007/S00048-007-0277-7 © 2008 BIRKHÄUSER VERLAG, BASEL F & OST /L UNDSTÜCK Ein bisher unbekanntes Zeitzeugnis. F Otto Warburgs Tagebuchnotizen von Februar–April 1945 Kärin Nickelsen Warburg’s diary notes February–April 1945 Personal notes in the form of a diary, written by the German cell biologist Otto Warburg in the weeks before the collapse of Germany’s Third Reich (Feb.-April 1945), were found at the end of one of his labo- ratory notebooks, which are preserved in the Archives of the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities. These notes are unique in form and content: there seem to be no other surviving diary notes of this type. Written from a very personal perspective, they provide a detailed account of how Warburg experienced local events in this decisive and turbulent period. Furthermore, they clearly demonstrate Warburg’s embittered attitude towards some of his long-standing collaborators, whom he suspected of having denounced him to the Nazi authorities. In this paper, Warburg’s notes are fully transcribed and integrated into the historical context. Keywords: Otto Warburg, Kaiser-Wilhelm-Society, National Socialism, diary notes Schlüsselwörter: Otto Warburg, Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft, Nationalsozialismus, Tagebuchnotizen | downloaded: 29.9.2021 Otto Warburg (1883–1970) ist in der Wissenschaftsgeschichte vor allem bekannt für seine bahnbrechenden Arbeiten zur Zellatmung, für die ihm 1931 der Nobelpreis verliehen wurde.1 In anderen Kontexten wiederum ist er bekannt als einer der ganz wenigen Wissenschaftler jüdischer Abstam- mung, die während der gesamten Zeit des Nationalsozialismus in Amt und Würden blieben: Nicht nur wurde Warburg nicht deportiert, er blieb bis 1945 Direktor des Kaiser-Wilhelm-Instituts (KWI) für Zellphysiologie in Berlin-Dahlem.2 Unter anderem stand er eigenen Angaben zufolge bis 1937 unter dem persönlichen Schutz von Friedrich Glum, damals Generaldirektor der Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft (Werner 1991: 284). -

Einstein and Physics Hundred Years Ago∗

Vol. 37 (2006) ACTA PHYSICA POLONICA B No 1 EINSTEIN AND PHYSICS HUNDRED YEARS AGO∗ Andrzej K. Wróblewski Physics Department, Warsaw University Hoża 69, 00-681 Warszawa, Poland [email protected] (Received November 15, 2005) In 1905 Albert Einstein published four papers which revolutionized physics. Einstein’s ideas concerning energy quanta and electrodynamics of moving bodies were received with scepticism which only very slowly went away in spite of their solid experimental confirmation. PACS numbers: 01.65.+g 1. Physics around 1900 At the turn of the XX century most scientists regarded physics as an almost completed science which was able to explain all known physical phe- nomena. It appeared to be a magnificent structure supported by the three mighty pillars: Newton’s mechanics, Maxwell’s electrodynamics, and ther- modynamics. For the celebrated French chemist Marcellin Berthelot there were no major unsolved problems left in science and the world was without mystery. Le monde est aujourd’hui sans mystère— he confidently wrote in 1885 [1]. Albert A. Michelson was of the opinion that “The more important fundamen- tal laws and facts of physical science have all been discovered, and these are now so firmly established that the possibility of their ever being supplanted in consequence of new discoveries is exceedingly remote . Our future dis- coveries must be looked for in the sixth place of decimals” [2]. Physics was not only effective but also perfect and beautiful. Henri Poincaré maintained that “The theory of light based on the works of Fresnel and his successors is the most perfect of all the theories of physics” [3]. -

EINSTEIN and NAZI PHYSICS When Science Meets Ideology and Prejudice

MONOGRAPH Mètode Science Studies Journal, 10 (2020): 147-155. University of Valencia. DOI: 10.7203/metode.10.13472 ISSN: 2174-3487. eISSN: 2174-9221. Submitted: 29/11/2018. Approved: 23/05/2019. EINSTEIN AND NAZI PHYSICS When science meets ideology and prejudice PHILIP BALL In the 1920s and 30s, in a Germany with widespread and growing anti-Semitism, and later with the rise of Nazism, Albert Einstein’s physics faced hostility and was attacked on racial grounds. That assault was orchestrated by two Nobel laureates in physics, who asserted that stereotypical racial features are exhibited in scientific thinking. Their actions show how ideology can infect and inflect science. Reviewing this episode in the current context remains an instructive and cautionary tale. Keywords: Albert Einstein, Nazism, anti-Semitism, science and ideology. It was German society, Einstein said, that revealed from epidemiology and research into disease (the to him his Jewishness. «This discovery was brought connection of smoking to cancer, and of HIV to home to me by non-Jews rather than Jews», he wrote AIDS) to climate change, this idea perhaps should in 1929 (cited in Folsing, 1998, p. 488). come as no surprise. But it is for that very reason that Shortly after the boycott of Jewish businesses at the the hostility Einstein’s physics sometimes encountered start of April 1933, the German Students Association, in Germany in the 1920s and 30s remains an emboldened by Hitler’s rise to total power, declared instructive and cautionary tale. that literature should be cleansed of the «un-German spirit». The result, on 10 May, was a ritualistic ■ AGAINST RELATIVITY burning of tens of thousands of books «marred» by Jewish intellectualism. -

Basic Research in the Max Planck Society Science Policy in the Federal Republic of Germany, 1945–1970

Chapter 5 Basic Research in the Max Planck Society Science Policy in the Federal Republic of Germany, 1945–1970 Carola Sachse ላሌ The Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science (MPG, Max- Planck-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften) is commonly consid- ered a stronghold of basic research in the German research landscape. When it was reestablished in 1948 in the Western zones of occupation, the society adopted the defi ning part of its predecessor’s name, the Kaiser Wilhelm So- ciety for the Advancement of Science (KWG, Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften), which had been founded in 1911. In contrast to its organizational counterpart, the Fraunhofer Society for the Ad- vancement of Applied Research (Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der angewandten Forschung), whose distinctive purpose has been incorporated into its name since its foundation in 1949 (Trischler and vom Bruch 1999), the MPG did not include the term “basic research” in its full name, nor does the term appear in any of its statutes of the last one hundred years. The offi - cial documents of the MPG instead refer to “scientifi c research” in the broad German sense of wissenschaftliche Forschung and combine it in varying formu- lations with the terms “freedom” and “independence.”1 Both of these terms are cornerstones in what became known as Harnack- Prinzip (Harnack principle). Named after Adolf von Harnack, the initiator and fi rst and longtime serving president of the KWG, this principle included two main aspects: fi rst, institutes should be founded only if a man was avail- able (women were not considered) for the post of managing director “who has This open access library edition is supported by the University of Bonn. -

Particle Detectors Lecture Notes

Lecture Notes Heidelberg, Summer Term 2011 The Physics of Particle Detectors Hans-Christian Schultz-Coulon Kirchhoff-Institut für Physik Introduction Historical Developments Historical Development γ-rays First 1896 Detection of α-, β- and γ-rays 1896 β-rays Image of Becquerel's photographic plate which has been An x-ray picture taken by Wilhelm Röntgen of Albert von fogged by exposure to radiation from a uranium salt. Kölliker's hand at a public lecture on 23 January 1896. Historical Development Rutherford's scattering experiment Microscope + Scintillating ZnS screen Schematic view of Rutherford experiment 1911 Rutherford's original experimental setup Historical Development Detection of cosmic rays [Hess 1912; Nobel prize 1936] ! "# Electrometer Cylinder from Wulf [2 cm diameter] Mirror Strings Microscope Natrium ! !""#$%&'()*+,-)./0)1&$23456/)78096$/'9::9098)1912 $%&!'()*+,-.%!/0&1.)%21331&10!,0%))0!%42%!56784210462!1(,!9624,10462,:177%&!(2;! '()*+,-.%2!<=%4*1;%2%)%:0&67%0%&!;1&>!Victor F. Hess before his 1912 balloon flight in Austria during which he discovered cosmic rays. ?40! @4)*%! ;%&! /0%)),-.&1(8%! A! )1,,%2! ,4-.!;4%!BC;%2!;%,!D)%:0&67%0%&,!(7!;4%! EC2F,1-.,%!;%,!/0&1.)%21331&10,!;&%.%2G!(7!%42%!*H&!;4%!A8)%,(2F!FH2,04F%!I6,40462! %42,0%))%2! J(! :K22%2>! L10&4(7! =4&;! M%&=%2;%0G! (7! ;4%! E(*0! 47! 922%&%2! ;%,! 9624,10462,M6)(7%2!M62!B%(-.04F:%40!*&%4!J(!.1)0%2>! $%&!422%&%G!:)%42%&%!<N)42;%&!;4%20!;%&!O8%&3&H*(2F!;%&!9,6)10462!;%,!P%&C0%,>!'4&;!%&! H8%&! ;4%! BC;%2! F%,%2:0G! ,6! M%&&42F%&0! ,4-.!;1,!1:04M%!9624,10462,M6)(7%2!1(*!;%2! -

The Collaboration of Mileva Marić and Albert Einstein

Asian Journal of Physics Vol 24, No 4 (2015) March The collaboration of Mileva Marić and Albert Einstein Estelle Asmodelle University of Central Lancashire School of Computing, Engineering and Physical Sciences, Preston, Lancashire, UK PR1 2HE. e-mail: [email protected]; Phone: +61 418 676 586. _____________________________________________________________________________________ This is a contemporary review of the involvement of Mileva Marić, Albert Einstein’s first wife, in his theoretical work between the period of 1900 to 1905. Separate biographies are outlined for both Mileva and Einstein, prior to their attendance at the Swiss Federal Polytechnic in Zürich in 1896. Then, a combined journal is described, detailing significant events. In additional to a biographical sketch, comments by various authors are compared and contrasted concerning two narratives: firstly, the sequence of events that happened and the couple’s relationship at particular times. Secondly, the contents of letters from both Einstein and Mileva. Some interpretations of the usage of pronouns in those letters during 1899 and 1905 are re-examined, and a different hypothesis regarding the usage of those pronouns is introduced. Various papers are examined and the content of each subsequent paper is compared to the work that Mileva was performing. With a different take, this treatment further suggests that the couple continued to work together much longer than other authors have indicated. We also evaluate critics and supporters of the hypothesis that Mileva was involved in Einstein’s work, and refocus this within a historical context, in terms of women in science in the late 19th century. Finally, the definition of, collaboration (co-authorship, specifically) is outlined. -

Bibliography Physics and Human Rights Michele Irwin and Juan C Gallardo August 18, 2017

Bibliography Physics and Human Rights Michele Irwin and Juan C Gallardo August 18, 2017 Physicists have been actively involved in the defense of Human Rights of colleague physicists, and scientists in general, around the world for a long time. What follows is a list of talks, articles and informed remembrances on Physics and Human Rights by physicist-activists that are available online. The selection is not exhaustive, on the contrary it just reflects our personal knowledge of recent publications; nevertheless, they are in our view representative of the indefatigable work of a large number of scientists affirming Human Rights and in defense of persecuted, in prison or at risk colleagues throughout the world. • “Ideas and Opinions” Albert Einstein Crown Publishers, 1954, 1982 The most definitive collection of Albert Einstein's writings, gathered under the supervision of Einstein himself. The selections range from his earliest days as a theoretical physicist to his death in 1955; from such subjects as relativity, nuclear war or peace, and religion and science, to human rights, economics, and government. • “Physics and Human Rights: Reflections on the past and the present” Joel L. Lebowitz Physikalische Blatter, Vol 56, issue 7-8, pages 51-54, July/August 2000 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/phbl.20000560712/pdf Based loosely on the Max von Laue lecture given at the German Physical Society's annual meeting in Dresden, 03/2000. This article focus on the moral and social responsibilities of scientists then -Nazi period in Germany- and now. Max von Laue's principled moral response at the time, distinguished him from many of his contemporary scientists. -

On the Planck-Einstein Relation Peter L

On the Planck-Einstein Relation Peter L. Ward US Geological Survey retired Science Is Never Settled PO Box 4875, Jackson, WY 83001 [email protected] Abstract The Planck-Einstein relation (E=hν), a formula integral to quantum mechanics, says that a quantum of energy (E), commonly thought of as a photon, is equal to the Planck constant (h) times a frequency of oscillation of an atomic oscillator (ν, the Greek letter nu). Yet frequency is not quantized—frequency of electromagnetic radiation is well known in Nature to be a continuum extending over at least 18 orders of magnitude from extremely low frequency (low-energy) radio signals to extremely high-frequency (high-energy) gamma rays. Therefore, electromagnetic energy (E), which simply equals a scaling constant times a continuum, must also be a continuum. We must conclude, therefore, that electromagnetic energy is not quantized at the microscopic level as widely assumed. Secondly, it makes no physical sense in Nature to add frequencies of electromagnetic radiation together in air or space—red light plus blue light does not equal ultraviolet light. Therefore, if E=hν, then it makes no physical sense to add together electromagnetic energies that are commonly thought of as photons. The purpose of this paper is to look at the history of E=hν and to examine the implications of accepting E=hν as a valid description of physical reality. Recognizing the role of E=hν makes the fundamental physics studied by quantum mechanics both physically intuitive and deterministic. Introduction On Sunday, October 7, 1900, Heinrich Rubens and wife visited Max Planck and wife for afternoon tea (Hoffmann, 2001). -

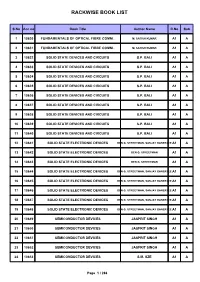

Rackwise Book List

RACKWISE BOOK LIST S.No Acc no Book Title Author Name R.No Sub 1 10630 FUNDAMENTALS OF OPTICAL FIBRE COMM.. M. SATISH KUMAR A1 A 2 10631 FUNDAMENTALS OF OPTICAL FIBRE COMM.. M. SATISH KUMAR A1 A 3 10632 SOLID STATE DEVICES AND CIRCUITS S.P. BALI A1 A 4 10633 SOLID STATE DEVICES AND CIRCUITS S.P. BALI A1 A 5 10634 SOLID STATE DEVICES AND CIRCUITS S.P. BALI A1 A 6 10635 SOLID STATE DEVICES AND CIRCUITS S.P. BALI A1 A 7 10636 SOLID STATE DEVICES AND CIRCUITS S.P. BALI A1 A 8 10637 SOLID STATE DEVICES AND CIRCUITS S.P. BALI A1 A 9 10638 SOLID STATE DEVICES AND CIRCUITS S.P. BALI A1 A 10 10639 SOLID STATE DEVICES AND CIRCUITS S.P. BALI A1 A 11 10640 SOLID STATE DEVICES AND CIRCUITS S.P. BALI A1 A 12 10641 SOLID STATE ELECTRONIC DEVICES BEN G. STREETMAN, SANJAY BANERJEE A1 A 13 10642 SOLID STATE ELECTRONIC DEVICES BEN G. STREETMAN A1 A 14 10643 SOLID STATE ELECTRONIC DEVICES BEN G. STREETMAN A1 A 15 10644 SOLID STATE ELECTRONIC DEVICES BEN G. STREETMAN, SANJAY BANERJEE A1 A 16 10645 SOLID STATE ELECTRONIC DEVICES BEN G. STREETMAN, SANJAY BANERJEE A1 A 17 10646 SOLID STATE ELECTRONIC DEVICES BEN G. STREETMAN, SANJAY BANERJEE A1 A 18 10647 SOLID STATE ELECTRONIC DEVICES BEN G. STREETMAN, SANJAY BANERJEE A1 A 19 10648 SOLID STATE ELECTRONIC DEVICES BEN G. STREETMAN, SANJAY BANERJEE A1 A 20 10649 SEMICONDUCTOR DEVICES JASPRIT SINGH A1 A 21 10650 SEMICONDUCTOR DEVICES JASPRIT SINGH A1 A 22 10651 SEMICONDUCTOR DEVICES JASPRIT SINGH A1 A 23 10652 SEMICONDUCTOR DEVICES JASPRIT SINGH A1 A 24 10653 SEMICONDUCTOR DEVICES S.M. -

Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project, 1939-1945: a Study in German Culture

Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project http://content.cdlib.org/xtf/view?docId=ft838nb56t&chunk.id=0&doc.v... Preferred Citation: Rose, Paul Lawrence. Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project, 1939-1945: A Study in German Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1998 1998. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft838nb56t/ Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project A Study in German Culture Paul Lawrence Rose UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford © 1998 The Regents of the University of California In affectionate memory of Brian Dalton (1924–1996), Scholar, gentleman, leader, friend And in honor of my father's 80th birthday Preferred Citation: Rose, Paul Lawrence. Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project, 1939-1945: A Study in German Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1998 1998. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft838nb56t/ In affectionate memory of Brian Dalton (1924–1996), Scholar, gentleman, leader, friend And in honor of my father's 80th birthday ― ix ― ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For hospitality during various phases of work on this book I am grateful to Aryeh Dvoretzky, Director of the Institute of Advanced Studies of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, whose invitation there allowed me to begin work on the book while on sabbatical leave from James Cook University of North Queensland, Australia, in 1983; and to those colleagues whose good offices made it possible for me to resume research on the subject while a visiting professor at York University and the University of Toronto, Canada, in 1990–92. Grants from the College of the Liberal Arts and the Institute for the Arts and Humanistic Studies of The Pennsylvania State University enabled me to complete the research and writing of the book. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: the PRINCIPAL UNCERTAINTY: U.S

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE PRINCIPAL UNCERTAINTY: U.S. ATOMIC INTELLIGENCE, 1942-1949 Vincent Jonathan Houghton, Doctor of Philosophy, 2013 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jon T. Sumida Department of History The subject of this dissertation is the U. S. atomic intelligence effort against both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in the period 1942-1949. Both of these intelligence efforts operated within the framework of an entirely new field of intelligence: scientific intelligence. Because of the atomic bomb, for the first time in history a nation’s scientific resources – the abilities of its scientists, the state of its research institutions and laboratories, its scientific educational system – became a key consideration in assessing a potential national security threat. Considering how successfully the United States conducted the atomic intelligence effort against the Germans in the Second World War, why was the United States Government unable to create an effective atomic intelligence apparatus to monitor Soviet scientific and nuclear capabilities? Put another way, why did the effort against the Soviet Union fail so badly, so completely, in all potential metrics – collection, analysis, and dissemination? In addition, did the general assessment of German and Soviet science lead to particular assumptions about their abilities to produce nuclear weapons? How did this assessment affect American presuppositions regarding the German and Soviet strategic threats? Despite extensive historical work on atomic intelligence, the current historiography has not adequately addressed these questions. THE PRINCIPAL UNCERTAINTY: U.S. ATOMIC INTELLIGENCE, 1942-1949 By Vincent Jonathan Houghton Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2013 Advisory Committee: Professor Jon T. -

Hitler's Uranium Club, the Secret Recordings at Farm Hall

HITLER’S URANIUM CLUB DER FARMHALLER NOBELPREIS-SONG (Melodie: Studio of seiner Reis) Detained since more than half a year Ein jeder weiss, das Unglueck kam Sind Hahn und wir in Farm Hall hier. Infolge splitting von Uran, Und fragt man wer is Schuld daran Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. The real reason nebenbei Die energy macht alles waermer. Ist weil we worked on nuclei. Only die Schweden werden aermer. Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. Die nuclei waren fuer den Krieg Auf akademisches Geheiss Und fuer den allgemeinen Sieg. Kriegt Deutschland einen Nobel-Preis. Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. Wie ist das moeglich, fragt man sich, In Oxford Street, da lebt ein Wesen, The story seems wunderlich. Die wird das heut’ mit Thraenen lesen. Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. Die Feldherrn, Staatschefs, Zeitungsknaben, Es fehlte damals nur ein atom, Ihn everyday im Munde haben. Haett er gesagt: I marry you madam. Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn. Even the sweethearts in the world(s) Dies ist nur unsre-erste Feier, Sie nennen sich jetzt: “Atom-girls.” Ich glaub die Sache wird noch teuer, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, Und fragt man, wer ist Schuld daran, So ist die Antwort: Otto Hahn.