Chopin and the G Minor Ballade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Young Narcyza Żmichowska's Reception of Western Cultural

Rocznik Komparatystyczny – Comparative Yearbook – Komparatistisches Jahrbuch 7 (2016) DOI: 10.18276/rk.2016.7-16 Ursula Phillips UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies (SSEES) With Open Eyes: The Young Narcyza Żmichowska’s Reception of Western Cultural Influences Narcyza Żmichowska (1819–1876) is not a name instantly recognizable outside Poland. In the English-speaking world, however, she is not unknown thanks to research on women’s history, where she is usually discussed in connection with the group of women with whom she was associated in the 1840s known as the Enthu- siasts (Fraisse and Perrot, 1993: 485). It is thanks to the appearance of Grażyna Borkowska’s book in English (2001) that her achievements as a literary author have become better known among Slavists and women’s literature researchers outside Poland. An English translation of Żmichowska’s best known novel Poganka (The Heathen) appeared in 2012 with a substantial introduction placing the work in both its Polish and European contemporary contexts (Żmichowska, 2012). Recently, this novel has featured alongside works by Charlotte Brontë, Daphne du Maurier and others, in a PhD dissertation inspired by psychoanalytic theories of femininity and mirroring, thereby proving her potential for comparative analysis (Naszkowska, 2012). The aim of the current article is to discuss this non-Polish context, and how foreign inspirations made their way into Żmichowska’s work and thinking. Like many other Polish cultural figures, Żmichowska maintained a close con- nection with France, although she never became an émigrée. Her literary activity is a testament nonetheless to how, despite spending more or less her whole life in the partitioned Polish lands, mostly in the Russian partition but also in the 1840s in the Poznań region of the Prussian, she was able to keep abreast of philosophical, political and literary developments in France and Germany and, in the latter part of her life, in Britain, North America, Italy and Scandinavia. -

Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Xian, Qiao-Shuang, "Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études"" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2432. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2432 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. REDISCOVERING FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN’S TROIS NOUVELLES ÉTUDES A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Qiao-Shuang Xian B.M., Columbus State University, 1996 M.M., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF EXAMPLES ………………………………………………………………………. iii LIST OF FIGURES …………………………………………………………………………… v ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………………………………… vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………….. 1 The Rise of Piano Methods …………………………………………………………….. 1 The Méthode des Méthodes de piano of 1840 -

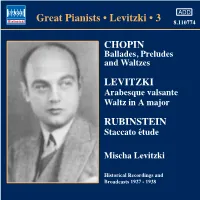

Print 110774Bk Levitzki

110774bk Levitzki 8/7/04 8:02 pm Page 5 Mischa Levitzki: Piano Recordings Vol. 3 Also available on Naxos ADD Gramophone Company Ltd., 1927-1933 RACHMANINOV: CHOPIN: @ Prelude in G minor, Op. 23, No. 5 3:22 Great Pianists • Levitzki • 3 8.110774 1 Prelude in C major, Op. 28 0:55 Recorded 21st November 1929 2 Prelude in A major, Op. 28, No. 7 0:55 Matrix Cc 18200-1a; Cat. D 1809 3 Prelude in F major, Op. 28, No. 23 1:24 Recorded 21st November 1929 RCA Victor, 1938 Matrix Bb 18113-3a; Cat.DA1223 LEVITZKI: 4 Waltz No. 8 in A flat major, Op. 64, No. 3 3:00 # Waltz in A major, Op. 2 1:46 CHOPIN Recorded 19th November 1928 Recorded 5th May 1938; Matrix Cc 14770-1; Cat.ED18 Matrices BS 023101-1, BS 023101-1A (NP), Ballades, Preludes BS 023101-2, BS 023101-2A (NP); Cat. 2008-A 5 Waltz No. 11 in G flat major, $ Arabesque valsante, Op. 6 3:23 and Waltzes Op. 70, No. 1 2:26 Recorded 5th May 1938; Recorded 19th November 1928 Matrices BS 023100-1, BS 023100-1A (NP), Matrix Cc 14769-3; Cat.ED18 BS 023100-2, BS 023100-2A (NP), BS 023100-3, 6 Ballade No. 3 in A flat major, Op. 47 6:26 BS023100-3A (NP); Cat. 2008-B Recorded 22nd November 1928 Broadcasts LEVITZKI Matrices Bb 11786-5 and 11787-5; Cat.EW64 26th January, 1935: 7 Nocturne No. 5 in F sharp major, CHOPIN: Arabesque valsante Op. 15, No. -

Halle, the City of Music a Journey Through the History of Music

HALLE, THE CITY OF MUSIC A JOURNEY THROUGH THE HISTORY OF MUSIC 8 WC 9 Wardrobe Ticket office Tour 1 2 7 6 5 4 3 EXHIBITION IN WILHELM FRIEDEMANN BACH HOUSE Wilhelm Friedemann Bach House at Grosse Klausstrasse 12 is one of the most important Renaissance houses in the city of Halle and was formerly the place of residence of Johann Sebastian Bach’s eldest son. An extension built in 1835 houses on its first floor an exhibition which is well worth a visit: “Halle, the City of Music”. 1 Halle, the City of Music 5 Johann Friedrich Reichardt and Carl Loewe Halle has a rich musical history, traces of which are still Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1752–1814) is known as a partially visible today. Minnesingers and wandering musicographer, composer and the publisher of numerous musicians visited Giebichenstein Castle back in the lieder. He moved to Giebichenstein near Halle in 1794. Middle Ages. The Moritzburg and later the Neue On his estate, which was viewed as the centre of Residenz court under Cardinal Albrecht von Brandenburg Romanticism, he received numerous famous figures reached its heyday during the Renaissance. The city’s including Ludwig Tieck, Clemens Brentano, Novalis, three ancient churches – Marktkirche, St. Ulrich and St. Joseph von Eichendorff and Johann Wolfgang von Moritz – have always played an important role in Goethe. He organised musical performances at his home musical culture. Germany’s oldest boys’ choir, the in which his musically gifted daughters and the young Stadtsingechor, sang here. With the founding of Halle Carl Loewe took part. University in 1694, the middle classes began to develop Carl Loewe (1796–1869), born in Löbejün, spent his and with them, a middle-class musical culture. -

Chopin: Visual Contexts

Interdisciplinary Studies in Musicology g, 2011 © Department of Musicology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland JACEK SZERSZENOWICZ (Łódź) Chopin: Visual Contexts ABSTRACT: The drawings, portraits and effigies of Chopin that were produced during his lifetime later became the basis for artists’ fantasies on the subject of his work. Just after the composer’s death, Teofil Kwiatkowski began to paint Bal w Hotel Lambert w Paryżu [Ball at the Hotel Lambert in Paris], symbolising the unfulfilled hopes of the Polish Great Emi gration that Chopin would join the mission to raise the spirit of the nation. Henryk Siemiradzki recalled the young musician’s visit to the Radziwiłł Palace in Poznań. The composer’s likeness appeared in symbolic representations of a psychological, ethnological and historical character. Traditional roots are referred to in the paintings of Feliks Wygrzywalski, Mazurek - grający Chopin [Mazurka - Chopin at the piano], with a couple of dancers in folk costume, and Stanisław Zawadzki, depicting the com poser with a roll of paper in his hand against the background of a forest, into the wall of which silhouettes of country children are merged, personifying folk music. Pictorial tales about music were also popularised by postcards. On one anonymous postcard, a ghost hovers over the playing musician, and the title Marsz żałobny Szopena [Chopin’s funeral march] suggests the connection with real apparitions that the composer occasional had when performing that work. In the visualisation of music, artists were often assisted by poets, who suggested associations and symbols. Correlations of content and style can be discerned, for ex ample, between Władysław Podkowinski’s painting Marsz żałobny Szopena and Kor nel Ujejski’s earlier poem Marsz pogrzebowy [Funeral march]. -

Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 As a Contribution to the Violist's

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory Rafal Zyskowski Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zyskowski, Rafal, "A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3366. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A TALE OF LOVERS: CHOPIN’S NOCTURNE OP. 27, NO. 2 AS A CONTRIBUTION TO THE VIOLIST’S REPERTORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Rafal Zyskowski B.M., Louisiana State University, 2008 M.M., Indiana University, 2010 May 2014 ©2014 Rafal Zyskowski All rights reserved ii Dedicated to Ms. Dorothy Harman, my best friend ever iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As always in life, the final outcome of our work results from a contribution that was made in one way or another by a great number of people. Thus, I want to express my gratitude to at least some of them. -

Interpreting Tempo and Rubato in Chopin's Music

Interpreting tempo and rubato in Chopin’s music: A matter of tradition or individual style? Li-San Ting A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of the Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences June 2013 ABSTRACT The main goal of this thesis is to gain a greater understanding of Chopin performance and interpretation, particularly in relation to tempo and rubato. This thesis is a comparative study between pianists who are associated with the Chopin tradition, primarily the Polish pianists of the early twentieth century, along with French pianists who are connected to Chopin via pedagogical lineage, and several modern pianists playing on period instruments. Through a detailed analysis of tempo and rubato in selected recordings, this thesis will explore the notions of tradition and individuality in Chopin playing, based on principles of pianism and pedagogy that emerge in Chopin’s writings, his composition, and his students’ accounts. Many pianists and teachers assume that a tradition in playing Chopin exists but the basis for this notion is often not made clear. Certain pianists are considered part of the Chopin tradition because of their indirect pedagogical connection to Chopin. I will investigate claims about tradition in Chopin playing in relation to tempo and rubato and highlight similarities and differences in the playing of pianists of the same or different nationality, pedagogical line or era. I will reveal how the literature on Chopin’s principles regarding tempo and rubato relates to any common or unique traits found in selected recordings. -

Adam Mickiewicz's

Readings - a journal for scholars and readers Volume 1 (2015), Issue 2 Adam Mickiewicz’s “Crimean Sonnets” – a clash of two cultures and a poetic journey into the Romantic self Olga Lenczewska, University of Oxford The paper analyses Adam Mickiewicz’s poetic cycle ‘Crimean Sonnets’ (1826) as one of the most prominent examples of early Romanticism in Poland, setting it across the background of Poland’s troubled history and Mickiewicz’s exile to Russia. I argue that the context in which Mickiewicz created the cycle as well as the final product itself influenced the way in which Polish Romanticism developed and matured. The sonnets show an internal evolution of the subject who learns of his Romantic nature and his artistic vocation through an exploration of a foreign land, therefore accompanying his physical journey with a spiritual one that gradually becomes the main theme of the ‘Crimean Sonnets’. In the first part of the paper I present the philosophy of the European Romanticism, situate it in the Polish historical context, and describe the formal structure of the Crimean cycle. In the second part of the paper I analyse five selected sonnets from the cycle in order to demonstrate the poetic journey of the subject-artist, centred around the epistemological difference between the Classical concept of ‘knowing’ and the Romantic act of ‘exploring’. Introduction The purpose of this essay is to present Adam Mickiewicz's “Crimean Sonnets” cycle – a piece very representative of early Polish Romanticism – in the light of the social and historical events that were crucial for the rise of Romantic literature in Poland, with Mickiewicz as a prize example. -

Nineteenth-Century French Challenges to the Liberal Image of Russia

Ezequiel Adamovsky Russia as a Space of Hope: Nineteenth-century French Challenges to the Liberal Image of Russia Introduction Beginning with Montesquieu’s De l’esprit des lois, a particular perception of Russia emerged in France. To the traditional nega- tive image of Russia as a space of brutality and backwardness, Montesquieu now added a new insight into her ‘sociological’ otherness. In De l’esprit des lois Russia was characterized as a space marked by an absence. The missing element in Russian society was the independent intermediate corps that in other parts of Europe were the guardians of freedom. Thus, Russia’s back- wardness was explained by the lack of the very element that made Western Europe’s superiority. A similar conceptual frame was to become predominant in the French liberal tradition’s perception of Russia. After the disillusion in the progressive role of enlight- ened despotism — one must remember here Voltaire and the myth of Peter the Great and Catherine II — the French liberals went back to ‘sociological’ explanations of Russia’s backward- ness. However, for later liberals such as Diderot, Volney, Mably, Levesque or Louis-Philippe de Ségur the missing element was not so much the intermediate corps as the ‘third estate’.1 In the turn of liberalism from noble to bourgeois, the third estate — and later the ‘middle class’ — was thought to be the ‘yeast of freedom’ and the origin of progress and civilization. In the nineteenth century this liberal-bourgeois dichotomy of barbarian Russia (lacking a middle class) vs civilized Western Europe (the home of the middle class) became hegemonic in the mental map of French thought.2 European History Quarterly Copyright © 2003 SAGE Publications, London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi, Vol. -

Rachmaninoff's Early Piano Works and the Traces of Chopin's Influence

Rachmaninoff’s Early Piano works and the Traces of Chopin’s Influence: The Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 & The Moments Musicaux, Op.16 A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Division of Keyboard Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music by Sanghie Lee P.D., Indiana University, 2011 B.M., M.M., Yonsei University, Korea, 2007 Committee Chair: Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract This document examines two of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s early piano works, Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 (1892) and Moments Musicaux, Opus 16 (1896), as they relate to the piano works of Frédéric Chopin. The five short pieces that comprise Morceaux de Fantaisie and the six Moments Musicaux are reminiscent of many of Chopin’s piano works; even as the sets broadly build on his character genres such as the nocturne, barcarolle, etude, prelude, waltz, and berceuse, they also frequently are modeled on or reference specific Chopin pieces. This document identifies how Rachmaninoff’s sets specifically and generally show the influence of Chopin’s style and works, while exploring how Rachmaninoff used Chopin’s models to create and present his unique compositional identity. Through this investigation, performers can better understand Chopin’s influence on Rachmaninoff’s piano works, and therefore improve their interpretations of his music. ii Copyright © 2018 by Sanghie Lee All rights reserved iii Acknowledgements I cannot express my heartfelt gratitude enough to my dear teacher James Tocco, who gave me devoted guidance and inspirational teaching for years. -

Songs in Fixed Forms

Songs in Fixed Forms by Margaret P. Hasselman 1 Introduction Fourteenth century France saw the development of several well-defined song structures. In contrast to the earlier troubadours and trouveres, the 14th-century songwriters established standardized patterns drawn from dance forms. These patterns then set up definite expectations in the listeners. The three forms which became standard, which are known today by the French term "formes fixes" (fixed forms), were the virelai, ballade and rondeau, although those terms were rarely used in that sense before the middle of the 14th century. (An older fixed form, the lai, was used in the Roman de Fauvel (c. 1316), and during the rest of the century primarily by Guillaume de Machaut.) All three forms make use of certain basic structural principles: repetition and contrast of music; correspondence of music with poetic form (syllable count and rhyme); couplets, in which two similar phrases or sections end differently, with the second ending more final or "closed" than the first; and refrains, where repetition of both words and music create an emphatic reference point. Contents • Definitions • Historical Context • Character and Provenance, with reference to specific examples • Notes and Selected Bibliography Definitions The three structures can be summarized using the conventional letters of the alphabet for repeated sections. Upper-case letters indicate that both text and music are identical. Lower-case letters indicate that a section of music is repeated with different words, which necessarily follow the same poetic form and rhyme-scheme. 1. Virelai The virelai consists of a refrain; a contrasting verse section, beginning with a couplet (two halves with open and closed endings), and continuing with a section which uses the music and the poetic form of the refrain; and finally a reiteration of the refrain. -

Programa Del Otoño Musical Soriano 2016

PRESIDENCIA DE HONOR S.A.R LA INFANTA Dª MARGARITA DE BORBÓN Y EL EXCMO. SR. D. CARLOS ZURITA. DUQUES DE SORIA Director Festival: Jose Manuel Aceña Notas al programa: Sonia Gonzalo Delgado Diseño y maquetación: Estudioayllón Impresión: Imprenta Provincial de Soria Organiza: Plaza Mayor s/n. 42071· SORIA Tel: 975 23 41 14 / 975 23 28 69 [email protected] www.soria.es/festivalmusical Dep. Leg: SO - 55/2016 Saluda del Alcalde Estimados amigos, estimadas amigas, Gracias por compartir un año más esta cita con la música y la cultura en nuestra Ciudad que es el Otoño Musical Soriano. Como podrán com- probar en este programa de mano, la vigesimocuarta edición de nuestro Festival refleja su carácter accesible, atractivo, completo y ambicioso que reedita la conexión mágica con ustedes, el público, verdadero artífice de que el Otoño Musical Soriano se supere año a año, convirtiéndose en uno de los principales festivales musicales a nivel europeo. Así lo atestigua el galardón “EFFE Label”, recibido el pasado año desde la Asociación Eu- ropea de Festivales como marca de calidad del Otoño Musical Soriano. A punto de celebrar 25 años de historia desde que el trabajo y el cariño del Maestro Odón Alonso hacia Soria alumbrara esta cita por primera vez, las máximas de compromiso con el talento artístico y la excelen- cia internacional están presentes desde la inauguración a la clausura gracias a la labor de su Director, el Maestro José Manuel Aceña, quien ha sabido comprender y transmitir el legado del Maestro Alonso. Sirvan estas líneas para reconocer una vez más su trabajo al frente del Festival.