Texas Historical Commission Staff

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lundberg Bakery HABS No. TX-3267 1006 Congress Avenue Austin

Lundberg Bakery HABS No. TX-3267 1006 Congress Avenue m Austin Travis County Texas 11 A Q C PHOTOGRAPHS HISTORICAL AM) DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Buildings Survey Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 2021*3 >S "U-K.2Jn-A\JST, \°i- HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY LUNDBERG BAKERY RABS NO. TX-3267 Location: 1006 Congress Avenue, Austin, Travis County, Texas, USGS Austin East Quadrangle, Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates: li+.621080.331+9i+10. Present Owner: State of Texas Texas Highway Department 11th and Brazos Streets Austin, Texas Present Occupant: Vacant. Significance: The Lundberg Bakery is an important commercial and historical landmark in Austin. Built in 1875-76, it first housed the successful bakery business of Charles Lundberg, and continued to be used as a bakery until 1937» Located within one block of both the Texas State Capitol and the Governor's Mansion, the restored Victorian structure makes a significant visual contribution to the Capitol Area. PART I: HISTORICAL INFORMATION A.' Physical History: 1. Date of erection: 1875-1876. 2. Architect: Unknown. 3. Original and subsequent owners: The following is an incomplete chain of title to the land on which the structure stands. Reference is to the Clerk's Office of the County of Travis, Texas. iQfh Deed December 17, l8T^, recorded December 19, l&lh in Volume 28, pages 107-108. Ernst Raven and wife to Charles Lundberg. North half of lot 2 in block 12U. 1909 Affidavit April 20, 1909, recorded April 23, 1909, in Volume 226, page h&5* Relates that Charles Lundberg died intestate on February 7, 1895. -

The City of Austin from 1839 to 1865 Author(S): Alex

The City of Austin from 1839 to 1865 Author(s): Alex. W. Terrell Source: The Quarterly of the Texas State Historical Association, Vol. 14, No. 2 (Oct., 1910), pp. 113-128 Published by: Texas State Historical Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30243064 Accessed: 15-06-2016 02:03 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Texas State Historical Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Quarterly of the Texas State Historical Association This content downloaded from 128.83.63.20 on Wed, 15 Jun 2016 02:03:12 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms The City of Austin from 1839 to 1865. 113 THE CITY OF AUSTIN FROM 1839 TO 1865 ALEX. W. TERRELL The ground on which the City of Austin is built was selected as the proper place for the Capital of the Republic of Texas in 1839, six years before annexation to the United States. How it happened that the seat of government was thus lo- cated, what public houses were then built for the Republic, when and how they were erected, and other matters of public inter- est connected with the early history of Austin should be made known to this generation before a knowledge of them fades into vague tradition. -

No. 21-0170 in the SUPREME COURT of TEXAS RESPONSE BY

FILED 21-0170 3/2/2021 10:56 AM tex-51063305 SUPREME COURT OF TEXAS BLAKE A. HAWTHORNE, CLERK No. 21-0170 _______________________________________ IN THE SUPREME COURT OF TEXAS _______________________________________ IN RE LINDA DURNIN, ERIC KROHN, AND MICHAEL LOVINS, Relators. _______________________________________ ORIGINAL PROCEEDING ______________________________________ RESPONSE BY CITY OF AUSTIN AND AUSTIN CITY COUNCIL IN OPPOSITION TO FIRST AMENDED ORIGINAL EMERGENCY PETITION FOR WRIT OF MANDAMUS _______________________________________ Anne L. Morgan, City Attorney Renea Hicks State Bar No. 14432400 LAW OFFICE OF Meghan L. Riley, Chief-Litigation RENEA HICKS State Bar No. 24049373 State Bar No. 09580400 CITY OF AUSTIN–LAW DEP’T. P.O. Box 303187 P.O. Box 1546 Austin, Texas 78703-0504 Austin, Texas 78767-1546 (512) 480-8231 (512) 974-2268 [email protected] ATTORNEYS FOR RESPONDENTS CITY OF AUSTIN AND AUSTIN CITY COUNCIL IDENTITY OF PARTIES AND COUNSEL Party’s name Party’s status Attorneys for parties LINDA DURNIN Relators Donna García Davidson ERIC KROHN Capitol Station, P.O. Box 12131 MICHAEL LOVINS Austin, Texas 78711 Bill Aleshire ALESHIRELAW, P.C. 3605 Shady Valley Dr. Austin, Texas 78739 CITY OF AUSTIN Respondents Renea Hicks AUSTIN CITY LAW OFFICE OF RENEA HICKS COUNCIL P.O. Box 303187 Austin, Texas 78703-0504 Anne L. Morgan, City Attorney Meghan L. Riley, Chief – Litiga- tion CITY OF AUSTIN–LAW DEP’T. P. O. Box 1546 Austin, Texas 78767-1546 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Identity of Parties and Counsel ........................................................ -

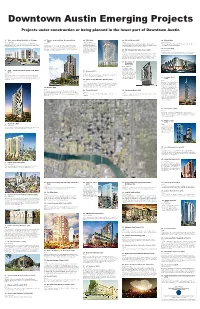

Downtown Austin Emerging Projects

Downtown Austin Emerging Projects Projects under construction or being planned in the lower part of Downtown Austin 1. 7th & Lamar (North Block, Phase II) (C2g) 11. Thomas C. Green Water Treatment Plant 20. 7Rio (R60) 28. 5th and Brazos (C54) 39. Eleven (R86) 8QGHU&RQVWUXFWLRQ (C56) 8QGHU&RQVWUXFWLRQ Planned 8QGHU&RQVWUXFWLRQ &RQVWUXFWLRQLVXQGHUZD\DWWKHVLWHRIWKHIRUPHU.$6(.9(7UDGLR Planned &RQVWUXFWLRQVWDUWHGLQ0D\ $QH[LVWLQJYDOHWSDUNLQJJDUDJHZLOOEHWRUQGRZQDQGUHSODFHGE\DQ :RUNFRQWLQXHVRQWKLVXQLWPXOWLIDPLO\SURMHFWRQ(WK6WUHHW VWXGLREXLOGLQJIRUWKHFRQVWUXFWLRQRIDQHZSDUNLQJJDUDJHZLWK 7KH*UHHQVLWHZLOOFRQVLVWRIVHYHUDOEXLOGLQJVXSWRVWRULHVWDOO RQWKLVXQLWDSDUWPHQW HLJKWVWRU\SDUNLQJJDUDJHZLWKVSDFHV7KDWJDUDJHVWUXFWXUHZLOODOVR RYHUORRNLQJ,DQGGRZQWRZQ$XVWLQ VIRIJURXQGÀRRUUHWDLO ,QFOXGLQJ%ORFN VHHEHORZ WKHSURMHFWZLOOKDYHPLOOLRQ WRZHUDW:WK6WUHHWDQG5LR LQFOXGHVTXDUHIHHWRIVWUHHWOHYHOUHWDLOVSDFH VTXDUHIHHWRIGHYHORSPHQWLQFOXGLQJDSDUWPHQWVVTIWRI *UDQGHE\&DOLIRUQLDEDVHG RI¿FHVSDFHDURRPKRWHODQGVTIWRIUHWDLO PRVWDORQJDQ GHYHORSPHQWFRPSDQ\&:6 40. Corazon (R66) H[WHQVLRQRIWKHQG6WUHHW'LVWULFW 7KHSURMHFWZDVGHVLJQHG 29. 5th & Brazos Mixed-Use Tower (C89) 8QGHU&RQVWUXFWLRQ E\ORFDODUFKLWHFWXUDO¿UP Planned 5KRGH3DUWQHUV &\SUHVV5HDO(VWDWH$GYLVHUVLVEXLOGLQJ&RUD]RQDYHUWLFDOPL[HGXVH $VN\VFUDSHURIXSWRVWRULHVZLWKKRWHOURRPVDQGUHVLGHQFHVDW(DVW SURMHFWWKDWZLOOLQFOXGHUHVLGHQWLDOXQLWVUHWDLODQGDUHVWDXUDQW )LIWKDQG%UD]RVVWUHHWVGRZQWRZQ7KHWRZHUFRXOGLQFOXGHRQHRUWZR KRWHOVDQGPRUHWKDQKRXVLQJXQLWVPRVWOLNHO\DSDUWPHQWV&KLFDJR EDVHG0DJHOODQ'HYHORSPHQW*URXSZRXOGGHYHORSWKHSURMHFWZLWK :DQ[LDQJ$PHULFD5HDO(VWDWH*URXSDOVREDVHGLQWKH&KLFDJRDUHD -

Women's Narratives of Racialized and Gendered Space in Austin, Texas

139 OMEN’S NARRATIVES OF RACIALIZED AND GENDERED SPACE IN AUSTIN, WTEXAS Martha Norkunas History Department, Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro ka tribina 39, vol. 46, 2016., str. 139-156 46, 2016., str. 39, vol. ka tribina š ! is article examines African American women’s movement in racialized and gendered space in Austin, Texas in the mid twentieth century, re) ecting on the relationship between race, gender, power and space. etnolo It draws on oral history interviews with African American women to consider how they negotiated the racialized and gendered geography of the city as well as the microspaces – especially downtown clothing stores – that were racialized and gendered in particular ways. Keywords: racialized space, gendered space, race, gender, geography, narrative, Austin Even though I knew there were… “di# erences” such as there were certain things we could not do, it was kind of like there were certain things you knew you could not and you just did not do it. Like you did not go to the water fountain that was for Whites and drink water there. If there was a store that you could not go into you did not go. Now what would hap- pen with reference to the shopping, African Americans could go into the stores, but you could not try on things. You could not try on a dress, shoes. Of course that eventually got be% er. (Overton 2009, April 6) Introduction1 In 2004 I began a project recording life history interviews with people who identify as Afri- can American, “in an e# ort to come to a deeper appreciation of the important events, values, and intellectual perspectives in the lives of African Americans, and to examine the impor- tance of race and racial identity in America”.2 Over the last twelve years my graduate stu- dents and I co-created life history interviews with 180 people in Texas and Tennessee, with birthdates ranging from 1920 to 1996. -

Cause No. ___GRAYSON COX, SABRINA BRADLEY, § in THE

4/26/2016 2:18:17 PM Velva L. Price District Clerk Travis County Cause No. D-1-GN-16-001762____________ D-1-GN-16-001762 Victoria Chambers GRAYSON COX, SABRINA BRADLEY, § IN THE DISTRICT COURT DANIEL DE LA GARZA, PIMPORN MAYO, § JEFFREY MAYO, RYDER JEANES, § JOSEPHINE MACALUSO, AMITY § COURTOIS, PHILIP COURTOIS, ANDREW § BRADFORD, MATTHEW PERRY, § TIMOTHY HAHN, GARY CULPEPPER, § CHERIE HAVARD, ANDREW COULSON, § LANITH DERRYBERRY, LINDA § 126th _____ JUDICIAL DISTRICT DERRYBERRY, ROSEANNE GIORDANI, § BETTY LITTRELL, and BENNETT BRIER, § § Plaintiffs, § v. § § CITY OF AUSTIN, § § Defendant. § TRAVIS COUNTY, TEXAS PLAINTIFFS’ ORIGINAL PETITION FOR DECLARATORY JUDGMENT Plaintiffs Grayson Cox, et al, file this petition for declaratory judgment, complaining of the City of Austin and seeking a declaratory judgment determining and confirming certain important rights guaranteed to them by state statute to protect the use and enjoyment of their property and homes. A. SUMMARY OF THE CASE AND REQUESTED RELIEF 1. This case involves the interpretation of the Valid Petition Rights section of the Texas Zoning Enabling Act, Texas Local Government Code Section 211.006(d) (the “Valid Petition Rights Statute”). That statute requires a ¾ vote of a City Council to approve any change in zoning regulations that are protested by at least 20% of the landowners in the area. 1 The requisite 20% of the neighboring landowners have submitted valid petitions objecting to the approval of the proposed zoning regulation changes for the Grove at Shoal Creek Planned Unit Development (herein “Grove PUD”). That Grove PUD is proposed as a high-density mixed-use development on a 76 acre tract of land at 4205 Bull Creek Road in Austin, Texas, commonly called the “Bull Creek Tract.” 2. -

The Central Austin Combined Neighborhood Plan

ORDINANCE NO. 040826-56 AN ORDINANCE AMENDING THE AUSTIN TOMORROW COMPREHENSIVE PLAN BY ADOPTING THE CENTRAL AUSTIN COMBINED NEIGHBORHOOD PLAN. BE IT ORDAINED BY THE CITY COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF AUSTIN: PARTI. Findings. (A) In 1979, the Cily Council adopted the "Austin Tomorrow Comprehensive Plan." (B) Article X, Section 5 of the City Charter authorizes the City Council to adopt by ordinance additional elements of a comprehensive plan that are necessary or desirable to establish and implement policies for growth, development, and beautification, including neighborhood, community, or area-wide plans. (C) In December 2002, the Central Austin neighborhood was selected to work with the City to complete a neighborhood plan. The Central Austin Combined Neighborhood Plan followed a process first outlined by the Citizens' Planning Committee in 1995, and refined by the Ad Hoc Neighborhood Planning Committee in 1996. The City Council endorsed this approach for neighborhood planning in a 1997 resolution. This process mandated representation of all of the stakeholders in the neighborhood and required active public outreach. The City Council directed the Planning Commission to consider the plan in a 2002 resolution. During the planning process, the Central Austin Combined Neighborhood Planning Team gathered information and solicited public input through the following means: (1.) neighborhood planning team meetings; (2) collection of existing data; (3) neighborhood inventory; (4) neighborhood survey; (5) neighborhood workshops; (6) community-wide meetings; and (7) a neighborhood final survey. Page 1 of 3 (D) The Central Austin Combined Neighborhood Plan recommends action by the Central Austin Combined Neighborhood Planning Team, City staff, and by other agencies to preserve and improve the neighborhood. -

AASLH 2017 ANNUAL MEETING I AM History

AASLH 2017 ANNUAL MEETING I AM History AUSTIN, TEXAS, SEPTEMBER 6-9 JoinJoin UsUs inin T E a n d L O C S TA A L r H fo I S N TO IO R T Y IA C O S S A CONTENTS N 3 Why Come to Austin? PRE-MEETING WORKSHOPS 37 AASLH Institutional A 6 About Austin 20 Wednesday, September 6 Partners and Patrons C I 9 Featured Speakers 39 Special Thanks SESSIONS AND PROGRAMS R 11 Top 12 Reasons to Visit Austin 40 Come Early and Stay Late 22 Thursday, September 7 E 12 Meeting Highlights and Sponsors 41 Hotel and Travel 28 Friday, September 8 M 14 Schedule at a Glance 43 Registration 34 Saturday, September 9 A 16 Tours 19 Special Events AUSTIN!AUSTIN! T E a n d L O C S TA A L r H fo I S N TO IO R T Y IA C O S S A N othing can replace the opportunitiesC ontents that arise A C when you intersect with people coming together I R around common goals and interests. E M A 2 AUSTIN 2017 oted by Forbes as #1 among America’s fastest growing cities in 2016, Austin is continually redefining itself. Home of the state capital, the heart of live music, and a center for technology and innovation, its iconic slogan, “Keep Austin Weird,” embraces the individualistic spirit of an incredible city in the hill country of Texas. In Austin you’ll experience the richness in diversity of people, histories, cultures, and communities, from earliest settlement thousands of years in the past to the present day — all instrumental in the growth of one of the most unique states in the country. -

Tear It Down! Save It! Preservationists Have Gained the Upper Hand in Protecting Historic Buildings

Tear It Down! Save It! Preservationists have gained the upper hand in protecting historic buildings. Now the ques- tion is whether examples of modern architecture— such as these three buildings —deserve the same respect as the great buildings of the past. By Larry Van Dyne The church at 16th and I streets in downtown DC does not match the usual images of a vi- sually appealing house of worship. It bears no resemblance to the picturesque churches of New England with their white clapboard and soaring steeples. And it has none of the robust stonework and stained-glass windows of a Gothic cathedral. The Third Church of Christ, Scientist, is modern architecture. Octagonal in shape, its walls rise 60 feet in roughcast concrete with only a couple of windows and a cantilevered carillon interrupting the gray façade. Surrounded by an empty plaza, it leaves the impression of a supersized piece of abstract sculpture. The church sits on a prime tract of land just north of the White House. The site is so valua- ble that a Washington-based real-estate company, ICG Properties, which owns an office building next door, has bought the land under the church and an adjacent building originally owned by the Christian Science home church in Boston. It hopes to cut a deal with the local church to tear down its sanctuary and fill the assembled site with a large office complex. The congregation, which consists of only a few dozen members, is eager to make the deal — hoping to occupy a new church inside the complex. -

Assistant Director, Austin Water Employee Leadership & Development

Assistant Director, Austin Water Employee Leadership & Development CITY OF AUSTIN, TEXAS UNIQUE OPPORTUNITY The City of Austin is seeking a highly qualified individual to fill the Employee Leadership & Development Assistant Director position which reports to the Austin Water Director. AUSTIN, TEXAS This vibrant and dynamic city tops numerous lists for business, entertainment, and quality of life. One of the country’s most popular, high-profile “green” and culturally dynamic cities, Austin was selected as the “Best City for the Next Decade” (Kiplinger, 2010), the “Top Creative Center” in the US (Entrepreneur.com, 2010), #1 on the Best Place to Live in the U.S. and #4 on the Best Places to Retire (U.S. News & World Report, 2019) , and ranked in the top ten on Forbes list of America’s Best Employers for 2017. Austin’s vision is to be a beacon of sustainability, social equity, and economic opportunity; where diversity and creativity are celebrated; where community needs and values are recognized; where leadership comes from its community members, and where the necessities of life are affordable and accessible to all. Austin is a player on the international scene with such events as SXSW, Austin City Limits, Urban Music Fest, Austin Film Festival, Formula 1 and home to companies such as Apple, Samsung, Dell and Ascension Seton Health. From the home of state government and the University of Texas, to the Live Music Capital of the World and its growth as a film center, Austin has gained worldwide attention as a hub for education, business, health, and sustainability. The City offers a wide range of events, from music concerts, food festivals, and sports competitions to museum displays, exhibits, and family fun. -

804 Congress Ave. | Austin, Texas 78701

804 CONGRESS AVE. | AUSTIN, TEXAS 78701 FOR MORE JASON STEINBERG, SIOR MATT LEVIN, SIOR INFORMATION 512.505.0004 512.505.0001 PLEASE CONTACT j [email protected] [email protected] 812 SAN ANTONIO | SUITE 105 | AUSTIN, TEXAS 78701 | 512.505.0000 | WWW.ECRTX.COM 804 CONGRESS NEW STREETSCAPE THE BOSCHE-HOGG BUILDING 804 CONGRESS AVENUE | AUSTIN, TEXAS 78701 FOR LEASE OFFICE | FOR MORE JASON STEINBERG, SIOR MATT LEVIN, SIOR INFORMATION 512.505.0004 512.505.0001 PLEASE CONTACT j [email protected] [email protected] 812 SAN ANTONIO | SUITE 105 | AUSTIN, TEXAS 78701 | 512.505.0000 | WWW.ECRTX.COM 804 CONGRESS PROPERTY INFORMATION THE BOSCHE-HOGG BUILDING 804 CONGRESS AVENUE | AUSTIN, TEXAS 78701 AVAILABILITY FOR LEASE Suite 300 - 6,770 RSF Available 7/1/17 OFFICE | PROPERTY DESCRIPTION 804 Congress, also known as The Bosche-Hogg Building, is a historic office building located in the heart of Downtown Austin. Only three blocks from the State of Texas Capitol building, it is in close proximity to both the Court House and the University of Texas. The building was built in 1897 and has had significant recent renovations, including a new Café Medici coffee bar within the updated lobby as well as a offering a rare outdoor park. It is within walking distance to dozens of restaurants and attractions, making it ideal for professional and creative users. Creative office suites, premier signage, several parking options, and State of Texas Capitol views makes this an attractive office lease opportunity. FEATURES BUILDING LOCATION SUITES • Six-story office -

Ray Bromley Edward Durell Stone. from the International Style to a Personal Style1

DOI: 10.1283/fam/issn2039-0491/n47-2019/231 Ray Bromley Edward Durell Stone. From the International Style to a Personal style1 Abstract Edward Durell Stone (1902-1978) was an American modernist who devel- oped a unique signature style of ‘new romanticism’ during the middle phase of his career between 1954 and 1966. The style was employed in several dozen major architectural projects and it coincided with his second marriage. His first signature style project was the U.S. Embassy in New Delhi, and the most famous one is the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington D.C. He achieved temporary global renown with his design for the U.S. Pavilion at the Brussels World’s Fair in 1958. Sadly, his best projects are widely scattered and he has no significant signature style works in New York City, where he based his career. His current obscurity is explained by the eccentric character of his signature style, his transition from personal design to corporate replication, and the abandonment of signature design principles after the breakdown of his second marriage. Key-words Modernism — New Romanticism — Signature Style Edward Durell Stone (EDS, 1902-1978) was an American modernist and post-modernist architect, who studied art and architecture at the University of Arkansas, Harvard and M.I.T., but who never completed an academic degree. The high point of his student days was a two year 1927-1929 Rotch Fellowship to tour Europe, focusing mainly on the Mediterranean countries, and preparing many fine architectural renderings of historic buildings. His European travels and Rotch Fellowship drawings reflected a deep appreciation of Beaux Arts traditions, but also a growing interest in modernist architecture and functionalist ideals.