The Consent Problem in International Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jus Cogens As a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr

Penn State International Law Review Volume 29 Article 2 Number 2 Penn State International Law Review 9-1-2010 Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche Follow this and additional works at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Petsche, Dr. Markus (2010) "Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order," Penn State International Law Review: Vol. 29: No. 2, Article 2. Available at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr/vol29/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Penn State International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Articles I Jus Cogens as a Vision of the International Legal Order Dr. Markus Petsche* Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .............................................. 235 I. THE INAPPROPRIATENESS OF CHARACTERIZING JUS COGENS AS A RULE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND THE LIMITED RELEVANCE OF JUS COGENS FOR THE PRACTICE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW...................................238 A. FundamentalConceptual and Theoretical Flaws ofJus Cogens .................................... 238 1. Origins of Jus Cogens. .................. ..... 238 2. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking Substance........ 242 3. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Procedure for Its Determination. ............ ......... .......... 243 4. Jus Cogens as a Set of Norms Lacking a Proper Theoretical Basis.......................... 245 B. The Limited Relevance of Jus Cogens for the Law of Treaties: Rare and Unsuccessful Reliance on Jus * DEA (Paris 1); LL.M. (NYU); Ph.D. -

Philosophy 320: Knowledge and Assertion

Course Syllabus: Philosophy 320: Knowledge and Assertion Matthew A. Benton [email protected] Description This 300-level upper-division undergraduate course, intended primarily for philosophy majors, will cover the literature on a fascinating question that has recently surfaced at the intersection of epistemology and philosophy of language: whether knowledge is the norm of assertion. The idea behind such a view is that in our standard conversational contexts, one who flat-out asserts that something is the case somehow represents herself as knowing that thing, and thus, there is a norm to the effect that one ought not to flat-out assert something unless one knows it. Proponents of the knowledge-norm have appealed to several strands of data from ordinary conversation practice and problematic sentences to sup- port their view; but other philosophers have leveled counterarguments. This course will evaluate the debate, including the most recent installments from the cutting edge of the philosophical literature. The course will meet a demand amongst undergraduates to study this re- cently (and hotly) debated issue: the literature relating knowledge and assertion is new enough that it is not typically covered by other undergraduate courses in epistemology or philosophy of language. It will hold special appeal for un- dergraduates with cross-disciplinary interests in language, epistemology, and communal/social normativity, and will provide a rich background for those who want to do further advanced study in philosophy or linguistics. Course Requirements Weekly readings and mandatory class attendance; students missing more than 5 class sessions will have their final grade lowered a half grade for each additional absence. -

Indigenous and Tribal People's Rights Over Their Ancestral Lands

INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 56/09 30 December 2009 Original: Spanish INDIGENOUS AND TRIBAL PEOPLES’ RIGHTS OVER THEIR ANCESTRAL LANDS AND NATURAL RESOURCES Norms and Jurisprudence of the Inter‐American Human Rights System 2010 Internet: http://www.cidh.org E‐mail: [email protected] OAS Cataloging‐in‐Publication Data Derechos de los pueblos indígenas y tribales sobre sus tierras ancestrales y recursos naturales: Normas y jurisprudencia del sistema interamericano de derechos humanos = Indigenous and tribal people’s rights over their ancestral lands and natural resources: Norms and jurisprudence of the Inter‐American human rights system / [Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights.] p. ; cm. (OEA documentos oficiales ; OEA/Ser.L)(OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L) ISBN 978‐0‐8270‐5580‐3 1. Human rights‐‐America. 2. Indigenous peoples‐‐Civil rights‐‐America. 3. Indigenous peoples‐‐Land tenure‐‐America. 4. Indigenous peoples‐‐Legal status, laws, etc.‐‐America. 5. Natural resources‐‐Law and legislation‐‐America. I. Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights. II Series. III. Series. OAS official records ; OEA/Ser.L. OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc.56/09 Document published thanks to the financial support of Denmark and Spain Positions herein expressed are those of the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights and do not reflect the views of Denmark or Spain Approved by the Inter‐American Commission on Human Rights on December 30, 2009 INTER‐AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS MEMBERS Luz Patricia Mejía Guerrero Víctor E. Abramovich Felipe González Sir Clare Kamau Roberts Paulo Sérgio Pinheiro Florentín Meléndez Paolo G. Carozza ****** Executive Secretary: Santiago A. -

1 Epistemic Norms of Political Deliberation Fabienne Peter

Epistemic norms of political deliberation Fabienne Peter, University of Warwick ([email protected]) December 2020 Forthcoming in Michael Hannon and Jeroen de Ridder (eds.) Routledge Handbook of Political Epistemology (https://www.routledge.com/The-Routledge-Handbook-of-Political- Epistemology/Hannon-Ridder/p/book/9780367345907). Please cite the published version. Abstract Legitimate political decision-making is underpinned by well-ordered political deliberation, including by the decision-makers themselves, their advisory bodies, and the public at large. But what constitutes well-ordered political deliberation? The short answer to this question is that it’s political deliberation that is governed by relevant norms. In this chapter, I first discuss different types of norms that might govern well-ordered political deliberation. I then focus on one particular type of norms: epistemic norms. My aim in this chapter is to shed light on how the validity of contributions to political deliberation depends, inter alia, on the epistemic status of the claims made. 1. Introduction Political deliberation is the broad, multi-stranded process in which political proposals get considered and critically scrutinised.1 There are many forums in which political deliberation takes place. Some of them are formal institutions of government such as the cabinet and parliament. Other forums of political deliberation include advisory bodies, government agencies, political parties and interest groups, the press and other broadcasters, and, increasingly, social media platforms. The latter are not directly associated with political 1 I have received helpful comments on an earlier version of this chapter from Jeroen de Ridder, Michael Hannon, and an external referee. I also benefitted from conversations with Nathalie Ashton, Rowan Cruft, and Jonathan Heawood in the context of our ARHC project on Norms for the New Public Sphere and from discussions at a NYU Political Economy and Political Theory workshop, especially with Dimitri Landa, Ryan Pevnick, and Melissa Schwartzberg. -

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don't Have Sex Without Them

Rights, Respect, Responsibility: Don’t Have Sex Without Them A Lesson Plan from Rights, Respect, Responsibility: A K-12 Curriculum Fostering responsibility by respecting young people’s rights to honest sexuality education. ADVANCE PREPARATION FOR LESSON: NSES ALIGNMENT: • Download the YouTube video on consent, “2 Minutes Will By the end of 12th grade, Change the Way You Think About Consent,” at https://www. students will be able to: youtube.com/watch?v=laMtr-rUEmY. HR.12.CC.3 – Define sexual consent and explain its • Also download the trailer for Pitch Perfect 2 - The Ellen Show implications for sexual decision- version (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KBwOYQd21TY), making. queuing it up to play a brief clip between 2:10 and 2:27. PS.12.CC.3 – Explain why using tricks, threats or coercion in • If you cannot download and save these to your desktop in relationships is wrong. advance, talk with your school’s IT person to ensure you have HR.12.INF.2 – Analyze factors, internet access to that link during class. including alcohol and other substances, that can affect the • Print out the skit scenarios and cut out each pair, making sure ability to give or perceive the the correct person 1 goes with the correct person 2. Determine provision of consent to sexual how many pairs there will be in your class and make several activity. copies of each scenario, enough for each pair to get one. TARGET GRADE: Grade 10 LEARNING OBJECTIVES: Lesson 1 By the end of this lesson, students will be able to: 1. -

Zeszyt-1 I Lam.Indd

Krakowskie Studia z Historii Państwa i Prawa 2012; 5 (1), s. 41–49 doi: 10.4467/20844131KS.12.006.0907 MAREK STARÝ (The University of Finance and Administration in Prague) Political and administrative system of Waldstein’s Lands Abstract The aim of this paper is to identify and describe basic mutual and different political and administrative characteristics of the lands under the rule of imperial generalissimo Albrecht of Waldstein. This man of Europian importance created in the twenties of the 17th century the Duchy of Frýdlant in north-eastern part of Bohemian Kingdom, moreover he became the ruler of German Duchy of Mecklenburg, as well as Emperor’s vassal in two Silesian Principalities, Sagan (1627) and Glogow (1632). It is quite interest- ing to learn about his arrangements in individual domains and to see, how some general principles of his reign were combined with specifi c steps proceeded from older particular traditions. It also shows undoubtedly, that Waldstein was really brilliant organiser, administrator and lawgiver who deserves intensive attention of legal history. Key words: Albrecht of Waldstein (Wallenstein), Thirty Years War, history of administration, Silesia, Bohemian Kingdom, reign on the absolutistic foundations, Duchy of Friedland, Duchy of Glogow, Principality of Sagan Słowa klucze: Albrecht von Waldstein (Wallenstein), wojna trzydziestoletnia, historia administracji, Śląsk, Królestwo Czeskie, rządy absolutne, Księstwo Frydlandu, Księstwo Głogowskie, Księstwo Żagańskie Imperial generalissimo Albrecht of Waldstein (or Wallenstein) († 1634) is undoubt- edly among the most signifi cant fi gures of Czech history. His importance defi nitely goes beyond the nation’s borders. Since the 19th century, he has even been considered to be a great national fi gure by the Germans, thanks to Schiller’s well-known drama.1 Waldstein played a considerable role in the history of Poland, both as a co-creator of European politics and as a military leader, whose activities during the Thirty Years’ War had infl uenced the Polish Respublica. -

Lessons from the Rise and Demise of the Self-Declared Caliphate of the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq

IN A BROKEN DREAM: LESSONS FROM THE RISE AND DEMISE OF THE SELF-DECLARED CALIPHATE OF THE ISLAMIC STATE IN SYRIA AND IRAQ TAL MIMRAN* I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................77 II. THE PRINCIPLE OF SOVEREIGNTY AND THE INTERNATIONAL LEGAL ORDER.............................................79 III. THE CASE STUDYTHE ISLAMIC STATE BETWEEN 2014 AND 2017.......................................................................91 IV. THE DREAM OF THE CALIPHATE AND STATEHOOD................99 A. The Criteria for Statehood............................................100 1. Permanent Population............................................101 2. Defined Territory ....................................................102 3. Effective Government .............................................102 4. Capacity to Enter into Relations with Other States ............................................................103 B. What’s Recognition Got To Do with It? ........................103 V. FUNCTIONALISM, DETERRITORIALIZATION, AND THE ISLAMIC STATE IN THE AGE OF THE RISE OF NSAS............112 VI. CONCLUSION........................................................................127 I. INTRODUCTION The Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (Islamic State)1 is a terrorist organization that took over significant territories, in the context of the Syrian civil war,2 and declared itself a caliphate in June 2014.3 It transformed from a minor terrorist group into an alleged quasi-state, presenting capabilities and wealth like no * Doctorate -

Life with Augustine

Life with Augustine ...a course in his spirit and guidance for daily living By Edmond A. Maher ii Life with Augustine © 2002 Augustinian Press Australia Sydney, Australia. Acknowledgements: The author wishes to acknowledge and thank the following people: ► the Augustinian Province of Our Mother of Good Counsel, Australia, for support- ing this project, with special mention of Pat Fahey osa, Kevin Burman osa, Pat Codd osa and Peter Jones osa ► Laurence Mooney osa for assistance in editing ► Michael Morahan osa for formatting this 2nd Edition ► John Coles, Peter Gagan, Dr. Frank McGrath fms (Brisbane CEO), Benet Fonck ofm, Peter Keogh sfo for sharing their vast experience in adult education ► John Rotelle osa, for granting us permission to use his English translation of Tarcisius van Bavel’s work Augustine (full bibliography within) and for his scholarly advice Megan Atkins for her formatting suggestions in the 1st Edition, that have carried over into this the 2nd ► those generous people who have completed the 1st Edition and suggested valuable improvements, especially Kath Neehouse and friends at Villanova College, Brisbane Foreword 1 Dear Participant Saint Augustine of Hippo is a figure in our history who has appealed to the curiosity and imagination of many generations. He is well known for being both sinner and saint, for being a bishop yet also a fellow pilgrim on the journey to God. One of the most popular and attractive persons across many centuries, his influence on the church has continued to our current day. He is also renowned for his influ- ence in philosophy and psychology and even (in an indirect way) art, music and architecture. -

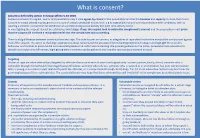

What Is Consent?

What is consent? Consent is defined by section 74 Sexual Offences Act 2003. Someone consents to vaginal, anal or oral penetration only if s/he agrees by choice to that penetration and has the freedom and capacity to make that choice. Consent to sexual activity may be given to one sort of sexual activity but not another, e.g.to vaginal but not anal sex or penetration with conditions, such as wearing a condom. Consent can be withdrawn at any time during sexual activity and each time activity occurs. In investigating the suspect, it must be established what steps, if any, the suspect took to obtain the complainant’s consent and the prosecution must prove that the suspect did not have a reasonable belief that the complainant was consenting. There is a big difference between consensual sex and rape. This aide focuses on consent, as allegations of rape often involve the word of the complainant against that of the suspect. The aim is to challenge assumptions about consent and the associated victim-blaming myths/stereotypes and highlight the suspect’s behaviour and motives to prove he did not reasonably believe the victim was consenting. We provide guidance to the police, prosecutors and advocates to identify and explain the differences, highlighting where evidence can be gathered and how the case can be presented in court. Targeting Victims of rape are often selected and targeted by offenders because of ease of access and opportunity - current partner, family, friend, someone who is vulnerable through mental health/ learning/physical difficulties, someone who sells sex, someone who is isolated or in an institution, has poor communication skills, is young, in a current or past relationship with the offender, or is compromised through drink/drugs. -

Norm (Philosophy) from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Norm (philosophy) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Norms are concepts (sentences) of practical import, oriented to effecting an action, rather than conceptual abstractions that describe, explain, and express. Normative sentences imply "ought-to" types of statements and assertions, in distinction to sentences that provide "is" types of statements and assertions. Common normative sentences include commands, permissions, and prohibitions; common normative abstract concepts include sincerity, justification, and honesty. A popular account of norms describes them as reasons to take action, to believe, and to feel. Types of norms Orders and permissions express norms. Such norm sentences do not describe how the world is, they rather prescribe how the world should be. Imperative sentences are the most obvious way to express norms, but declarative sentences also may be norms, as is the case with laws or 'principles'. Generally, whether an expression is a norm depends on what the sentence intends to assert. For instance, a sentence of the form "All Ravens are Black" could on one account be taken as descriptive, in which case an instance of a white raven would contradict it, or alternatively "All Ravens are Black" could be interpreted as a norm, in which case it stands as a principle and definition, so 'a white raven' would then not be a raven. Those norms purporting to create obligations (or duties) and permissions are called deontic norms (see also deontic logic). The concept of deontic norm is already an extension of a previous concept of norm, which would only include imperatives, that is, norms purporting to create duties. The understanding that permissions are norms in the same way was an important step in ethics and philosophy of law. -

The Maps and Mapmakers That Helped Define 20Th-Century

Historical research article / Lietuvos istorijos tematika The Maps and Mapmakers that Helped Define 20th-Century Lithuanian Boundaries - Part 1: Administrative Boundaries of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania Just Before the Partition of 1772 Andrew Kapochunas, Jersey City, New Jersey EN The leader of Russia, upon the pretext of protecting repeated and copied so many times as to pass for fact. minorities’ rights in a supposedly anarchic neighbor- So this first article in the series hopes to establish a ing country, occupies and annexes land belonging to valid visual starting point for the dismemberment of that sovereign nation. A primary driver of Russia’s the Grand Duchy within the Polish-Lithuanian Com- action: fear that Western-European thinking in the monwealth. Future installments will cover how the now-partitioned nation might spread, and cause prob- Russian Empire mapped their Grand Duchy territorial lems at home. I’m not talking about today’s headlines, acquisitions, the role that 19th and 20th century ethno- th century reality. but late 18 graphic and historical maps and their makers played How Lithuania went from being part of one of the in establishing boundaries after WWI, and the strug- largest countries in Europe in 1772 to one of the small- gles of 20th century mapmakers to accurately depict est after World War I is the subject of a series of arti- newly independent Lithuania’s boundaries. cles in which I hope to explain the role that maps and First, who was at the table carving up the Common- their makers played in determining, for instance, that wealth pie, and what did that pie consist of? Palanga wound up in independent Lithuania, while Trakai, Vilnius, Lyda and Gardinas didn’t. -

Informed Consent, AI Technologies, and Public Health Emergencies

future internet Review Trust, but Verify: Informed Consent, AI Technologies, and Public Health Emergencies Brian Pickering IT Innovation, Electronics and Computing, University of Southampton, University Road, Southampton SO17 1BJ, UK; [email protected] Abstract: To use technology or engage with research or medical treatment typically requires user consent: agreeing to terms of use with technology or services, or providing informed consent for research participation, for clinical trials and medical intervention, or as one legal basis for processing personal data. Introducing AI technologies, where explainability and trustworthiness are focus items for both government guidelines and responsible technologists, imposes additional challenges. Understanding enough of the technology to be able to make an informed decision, or consent, is essential but involves an acceptance of uncertain outcomes. Further, the contribution of AI- enabled technologies not least during the COVID-19 pandemic raises ethical concerns about the governance associated with their development and deployment. Using three typical scenarios— contact tracing, big data analytics and research during public emergencies—this paper explores a trust- based alternative to consent. Unlike existing consent-based mechanisms, this approach sees consent as a typical behavioural response to perceived contextual characteristics. Decisions to engage derive from the assumption that all relevant stakeholders including research participants will negotiate on an ongoing basis. Accepting dynamic negotiation between the main stakeholders as proposed here introduces a specifically socio–psychological perspective into the debate about human responses Citation: Pickering, B. Trust, but to artificial intelligence. This trust-based consent process leads to a set of recommendations for the Verify: Informed Consent, AI ethical use of advanced technologies as well as for the ethical review of applied research projects.