Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Habemus Papam

Fandango Portobello presents a Sacher Films, Fandango and le Pacte production in collaboration with Rai and France 3 Cinema HABEMUS PAPAM a film by Nanni Moretti Running Time: 104 minutes International Fandango Portobello sales: London office +44 20 7605 1396 [email protected] !"!1!"! ! SHORT SYNOPSIS The newly elected Pope suffers a panic attack just as he is due to appear on St Peter’s balcony to greet the faithful, who have been patiently awaiting the conclave’s decision. His advisors, unable to convince him he is the right man for the job, seek help from a renowned psychoanalyst (and atheist). But his fear of the responsibility suddenly thrust upon him is one that he must face on his own. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !"!2!"! CAST THE POPE MICHEL PICCOLI SPOKESPERSON JERZY STUHR CARDINAL GREGORI RENATO SCARPA CARDINAL BOLLATI FRANCO GRAZIOSI CARDINAL PESCARDONA CAMILLO MILLI CARDINAL CEVASCO ROBERTO NOBILE CARDINAL BRUMMER ULRICH VON DOBSCHÜTZ SWISS GUARD GIANLUCA GOBBI MALE PSYCHOTHERAPIST NANNI MORETTI FEMALE PSYCHOTHERAPIST MARGHERITA BUY CHILDREN CAMILLA RIDOLFI LEONARDO DELLA BIANCA THEATER COMPANY DARIO CANTARELLI MANUELA MANDRACCHIA ROSSANA MORTARA TECO CELIO ROBERTO DE FRANCESCO CHIARA CAUSA MASTER OF CEREMONIES MARIO SANTELLA CHIEF OF POLICE TONY LAUDADIO JOURNALIST ENRICO IANNIELLO A MOTHER CECILIA DAZZI SHOP ASSISTANT LUCIA MASCINO TV JOURNALIST MAURIZIO MANNONI HALL PORTER GIOVANNI LUDENO GIRL AT THE BAR GIULIA GIORDANO BARTENDER FRANCESCO BRANDI BOY AT THE BUS LEONARDO MADDALENA PRIEST SALVATORE MISCIO DOCTOR SALVATORE -

Les Meilleurs Films De 24 Images De 2005

Document generated on 09/28/2021 7:05 a.m. 24 images Les meilleurs films de 24 images de 2005 Jean Pierre Lefebvre Number 126, March–April 2006 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/8904ac See table of contents Publisher(s) 24/30 I/S ISSN 0707-9389 (print) 1923-5097 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this document (2006). Les meilleurs films de 24 images de 2005. 24 images, (126), 48–49. Tous droits réservés © 24/30 I/S, 2006 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Pouvaient être retenus les longs métrages présentés au Québec pour la première fois en de 2005, que ce soit à l'occasion d'une présentation lors d'un festival, d'une rétrospective ou d'une sortie en salles. Veuillez noter qu'une exception a été faite pour Sarabandqui 2005 avait bénéficié d'une unique projection en 2004 avant sa sortie en salles en 2005. La neuvaîne de Bernard Émond Plus tranquille et assuré que lent et austère, La neuvaine s'inscrit parfaitement dans le cinéma de la déflation qui a tant marqué les oeuvres de 2005 : récit flottant fait de microcellules de densité, rythme languide créant une nouvelle pulsion, images occupées uniquement à dire vrai, proposition de mise en scène aussi élégante que modeste. -

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

It 2.007 Vc Italian Films On

1 UW-Madison Learning Support Services Van Hise Hall - Room 274 rev. May 3, 2019 SET CALL NUMBER: IT 2.007 VC ITALIAN FILMS ON VIDEO, (Various distributors, 1986-1989) TYPE OF PROGRAM: Italian culture and civilization; Films DESCRIPTION: A series of classic Italian films either produced in Italy, directed by Italian directors, or on Italian subjects. Most are subtitled in English. Individual times are given for each videocassette. VIDEOTAPES ARE FOR RESERVE USE IN THE MEDIA LIBRARY ONLY -- Instructors may check them out for up to 24 hours for previewing purposes or to show them in class. See the Media Catalog for film series in other languages. AUDIENCE: Students of Italian, Italian literature, Italian film FORMAT: VHS; NTSC; DVD CONTENTS CALL NUMBER Il 7 e l’8 IT2.007.151 Italy. 90 min. DVD, requires region free player. In Italian. Ficarra & Picone. 8 1/2 IT2.007.013 1963. Italian with English subtitles. 138 min. B/W. VHS or DVD.Directed by Frederico Fellini, with Marcello Mastroianni. Fellini's semi- autobiographical masterpiece. Portrayal of a film director during the course of making a film and finding himself trapped by his fears and insecurities. 1900 (Novocento) IT2.007.131 1977. Italy. DVD. In Italian w/English subtitles. 315 min. Directed by Bernardo Bertolucci. With Robert De niro, Gerard Depardieu, Burt Lancaster and Donald Sutherland. Epic about friendship and war in Italy. Accattone IT2.007.053 Italy. 1961. Italian with English subtitles. 100 min. B/W. VHS or DVD. Directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini. Pasolini's first feature film. In the slums of Rome, Accattone "The Sponger" lives off the earnings of a prostitute. -

Sight & Sound Films of 2007

Sight & Sound Films of 2007 Each year we ask a selection of our contributors - reviewers and critics from around the world - for their five films of the year. It's a very loosely policed subjective selection, based on films the writer has seen and enjoyed that year, and we don't deny them the choice of films that haven't yet reached the UK. And we don't give them much time to ponder, either - just about a week. So below you'll find the familiar and the obscure, the new and the old. From this we put together the top ten you see here. What distinguishes this particular list is that it's been drawn up from one of the best years for all-round quality I can remember. 2007 has seen some extraordinary films. So all of the films in the ten are must-sees and so are many more. Enjoy. - Nick James, Editor. 1 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (Cristian Mungiu) 2 Inland Empire (David Lynch) 3 Zodiac (David Fincher) = 4 I’m Not There (Todd Haynes) The Lives of Others (Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck) 6 Silent Light (Carlos Reygadas) = 7 The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (Andrew Dominik) Syndromes and a Century (Apichatpong Weerasethakul) No Country for Old Men (Ethan and Joel Coen) Eastern Promises (David Cronenberg) 1 Table of Contents – alphabetical by critic Gilbert Adair (Critic and author, UK)............................................................................................4 Kaleem Aftab (Critic, The Independent, UK)...............................................................................4 Geoff Andrew (Critic -

Lightning in a Bottle

LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE A Sony Pictures Classics Release 106 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS STEVE BEEMAN LEE GINSBERG CARMELO PIRRONE 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, ANGELA GRESHAM SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 550 MADISON AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 8TH FLOOR PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 NEW YORK, NY 10022 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com 1 Volkswagen of America presents A Vulcan Production in Association with Cappa Productions & Jigsaw Productions Director of Photography – Lisa Rinzler Edited by – Bob Eisenhardt and Keith Salmon Musical Director – Steve Jordan Co-Producer - Richard Hutton Executive Producer - Martin Scorsese Executive Producers - Paul G. Allen and Jody Patton Producer- Jack Gulick Producer - Margaret Bodde Produced by Alex Gibney Directed by Antoine Fuqua Old or new, mainstream or underground, music is in our veins. Always has been, always will be. Whether it was a VW Bug on its way to Woodstock or a VW Bus road-tripping to one of the very first blues festivals. So here's to that spirit of nostalgia, and the soul of the blues. We're proud to sponsor of LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE. Stay tuned. Drivers Wanted. A Presentation of Vulcan Productions The Blues Music Foundation Dolby Digital Columbia Records Legacy Recordings Soundtrack album available on Columbia Records/Legacy Recordings/Sony Music Soundtrax Copyright © 2004 Blues Music Foundation, All Rights Reserved. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

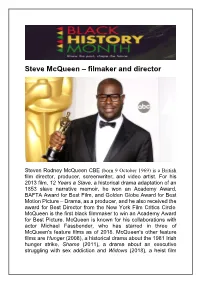

Steve Mcqueen – Filmaker and Director

Steve McQueen – filmaker and director Steven Rodney McQueen CBE (born 9 October 1969) is a British film director, producer, screenwriter, and video artist. For his 2013 film, 12 Years a Slave, a historical drama adaptation of an 1853 slave narrative memoir, he won an Academy Award, BAFTA Award for Best Film, and Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama, as a producer, and he also received the award for Best Director from the New York Film Critics Circle. McQueen is the first black filmmaker to win an Academy Award for Best Picture. McQueen is known for his collaborations with actor Michael Fassbender, who has starred in three of McQueen's feature films as of 2018. McQueen's other feature films are Hunger (2008), a historical drama about the 1981 Irish hunger strike, Shame (2011), a drama about an executive struggling with sex addiction and Widows (2018), a heist film about a group of women who vow to finish the job when their husbands die attempting to do so. McQueen was born in London and is of Grenadianand Trinidadian descent. He grew up in Hanwell, West London and went to Drayton Manor High School. In a 2014 interview, McQueen stated that he had a very bad experience in school, where he had been placed into a class for students believed best suited "for manual labour, more plumbers and builders, stuff like that." Later, the new head of the school would admit that there had been "institutional" racism at the time. McQueen added that he was dyslexic and had to wear an eyepatch due to a lazy eye, and reflected this may be why he was "put to one side very quickly". -

CEU Department of Medieval Studies Initiated Sessions at the 2003 and 2004 International Medieval Congresses in Connection with This Issue

ANNUAL OF MEDIEVAL STUDIES AT CEU VOL. 11 2005 Central European University Budapest ANNUAL OF MEDIEVAL STUDIES AT CEU VOL. 11 2005 Edited by Katalin Szende and Judith A. Rasson Central European University Budapest Department of Medieval Studies All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the permission of the publisher. Editorial Board János M. Bak, Gerhard Jaritz, Gábor Klaniczay, József Laszlovszky, Johannes Niehoff-Panagiotidis, István Perczel, Marianne Sághy Editors Katalin Szende and Judith A. Rasson Cover illustration Saint Sophia with Her Daughters from the Spiš region, ca. 1480–1490. Budapest, Hungarian National Gallery. Photo: Mihály Borsos Department of Medieval Studies Central European University H-1051 Budapest, Nádor u. 9., Hungary Postal address: H-1245 Budapest 5, P.O. Box 1082 E-mail: [email protected] Net: http://medstud.ceu.hu Copies can be ordered in the Department, and from the CEU Press http://www.ceupress.com/Order.html ISSN 1219-0616 Non-discrimination policy: CEU does not discriminate on the basis of—including, but not limited to—race, color, national or ethnic origin, religion, gender or sexual orientation in administering its educational policies, admissions policies, scholarship and loan programs, and athletic and other school-administered programs. © Central European University Produced by Archaeolingua Foundation & Publishing House TABLE OF CONTENTS Editors’ Preface ............................................................................................................. 5 I. ARTICLES AND STUDIES ......................................................................... 7 Magdolna Szilágyi Late Roman Bullae and Amulet Capsules in Pannonia ..................................... 9 Trpimir Vedriš Communities in Conflict: the Rivalry between the Cults of Sts. Anastasia and Chrysogonus in Medieval Zadar ...................................................................... -

Cineforumfest – 2015 2016

CineforumFEST – 2015 2016 mar 3/11 La famiglia Belier di Eric Lartigau con Evgueni Galperine, Sacha Galperine Brillante commedia francese supportata da una sceneggiatura solida, che mescola con perfetta misura umorismo, lacrime, disfunzioni, pregiudizi e canzoni mar 10/11 Youth - La giovinezza di Paolo Sorrentino con Michael Caine, Harvey Keitel, Rachel Weisz, Paul Dano, Jane Fonda Festival di Cannes 2015 - Due grandi attori per una riflessione giocosa sull’arte, la creazione, la bellezza (più seccature annesse, tipo la celebrità e i suoi obblighi) mar 17/11 Mia Madre di Nanni Moretti con Margherita Buy, John Turturro, Giulia Lazzarini, Nanni Moretti Un film profondo e sincero, un film sul cinema e sul rapporto tra realtà e finzione, un film che s'appresta ad essere un manifesto del nostro tempo complesso e problematico mar 24/11 Vizio di forma di Paul Thomas Anderson con Joaquin Phoenix, Josh Brolin, Benicio Del Toro Sotto le vesti lacere del noir si nasconde una complessa e stratificata riflessione sul trauma della fine di un'epoca mar 1/12 Roger Waters – The wall di Roger Waters, Sean Evans Un nuovo capitolo più che valido nella straordinaria storia cinematografica dei Pink Floyd mer 9/12 Forza maggiore di Ruben Östlund con Johannes Kuhnke, Lisa Loven Kongsli, Clara Wettergren Una conferma del talento dello svedese, entomologo dell'assurdo mar 15/12 Taxi Teheran di Jafar Panahi con Jafar Panahi, Hana Saeidi Un taxi attraversa le strade di Teheran in un giorno qualsiasi. Passeggeri di diversa estrazione sociale salgono e scendono dalla vettura. Alla guida non c'è un conducente qualsiasi ma Jafar Panahi stesso impegnato a girare un altro film 'proibito'. -

Westminsterresearch the Artist Biopic

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch The artist biopic: a historical analysis of narrative cinema, 1934- 2010 Bovey, D. This is an electronic version of a PhD thesis awarded by the University of Westminster. © Mr David Bovey, 2015. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the authors and/or copyright owners. Whilst further distribution of specific materials from within this archive is forbidden, you may freely distribute the URL of WestminsterResearch: ((http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/). In case of abuse or copyright appearing without permission e-mail [email protected] 1 THE ARTIST BIOPIC: A HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF NARRATIVE CINEMA, 1934-2010 DAVID ALLAN BOVEY A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Master of Philosophy December 2015 2 ABSTRACT The thesis provides an historical overview of the artist biopic that has emerged as a distinct sub-genre of the biopic as a whole, totalling some ninety films from Europe and America alone since the first talking artist biopic in 1934. Their making usually reflects a determination on the part of the director or star to see the artist as an alter-ego. Many of them were adaptations of successful literary works, which tempted financial backers by having a ready-made audience based on a pre-established reputation. The sub-genre’s development is explored via the grouping of films with associated themes and the use of case studies. -

W Talking Pictures

Wednesday 3 June at 20.30 (Part I) Wednesday 17 June at 20.30 Thursday 4 June at 20.30 (Part II) Francis Ford Coppola Ingmar Bergman Apocalypse Now (US) 1979 Fanny And Alexander (Sweden) 1982 “One of the great films of all time. It shames modern Hollywood’s “This exuberant, richly textured film, timidity. To watch it is to feel yourself lifted up to the heights where packed with life and incident, is the cinema can take you, but so rarely does.” (Roger Ebert, Chicago punctuated by a series of ritual family Sun-Times) “To look at APOCALYPSE NOW is to realize that most of us are gatherings for parties, funerals, weddings, fast forgetting what a movie looks like - a real movie, the last movie, and christenings. Ghosts are as corporeal an American masterpiece.” (Manohla Darghis, LA Weekly) “Remains a as living people. Seasons come and go; majestic explosion of pure cinema. It’s a hallucinatory poem of fear, tumultuous, traumatic events occur - projecting, in its scale and spirit, a messianic vision of human warfare Talking yet, as in a dream of childhood (the film’s stretched to the flashpoint of technological and moral breakdown.” perspective is that of Alexander), time is (Owen Gleiberman, Entertainment Weekly) “In spite of its limited oddly still.” (Philip French, The Observer) perspective on Vietnam, its churning, term-paperish exploration of “Emerges as a sumptuously produced Conrad and the near incoherence of its ending, it is a great movie. It Pictures period piece that is also a rich tapestry of grows richer and stranger with each viewing, and the restoration [in childhood memoirs and moods, fear and Redux] of scenes left in the cutting room two decades ago has only April - July 2009 fancy, employing all the manners and added to its sublimity.” (Dana Stevens, The New York Times) Audience means of the best of cinematic theatrical can choose the original version or the longer 2001 Redux version.