Prostitution and Power in Progressive-Era Texas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ludacris Word of Mouf Full Album

Ludacris, Word Of Mouf Full Album Zip 1 / 4 Ludacris, Word Of Mouf Full Album Zip 2 / 4 3 / 4 Word Of Mouf | Ludacris to stream in hi-fi, or to download in True CD Quality on Qobuz.com.. Play full-length songs from Word Of Mouf by Ludacris on your phone, computer and home audio system with Napster.. Ludacris - Word Of Mouf - Amazon.com Music. ... Listen to Word Of Mouf [Explicit] by Ludacris and 50 million songs with Amazon Music Unlimited. $9.99/month .... Download Word Of Mouf (Explicit) by Ludacris at Juno Download. Listen to this and ... Block Lockdown (album version (Explicit) feat Infamous 2-0). 07:48. 96.. 2001 - Ludacris - ''Wоrd Of Mouf''. Tracklist. 01. "Coming 2 America". 02. ... Tracklist. 01 - Intro. 02 - Georgia. 03 - Put Ya Hands Up. 04 - Word On The Street (Skit).. Word of Mouf is the third studio album by American rapper Ludacris; it was released on November 27, 2001, by Disturbing tha Peace and Def Jam South.. Word of Mouf by Ludacris songs free download.. Facebook; Twitter .. Explore the page to download mp3 songs or full album zip for free.. ludacris word of mouf zip ludacris word of mouf songs ludacris word of mouf download ludacris word of mouf full album . View credits, reviews, tracks and shop for the 2001 CD release of Word Of Mouf on Discogs. ... Word Of Mouf (CD, Album) album cover ... Tracklist Hide Credits .... Ludacris - Back for the First Time (Full album). Enoch; 16 ... Play & Download Ludacris - Word Of Mouf itunes zip Only On GangstaRapTalk the.. Download Word of Mouf 2001 Album by Ludacris in mp3 CBR online alongwith Karaoke. -

Copyright by Eric Alan Ratliff 2003

Copyright by Eric Alan Ratliff 2003 The Dissertation Committee for Eric Alan Ratliff Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Price of Passion: Performances of Consumption and Desire in the Philippine Go-Go Bar Committee: ____________________________________ Douglas Foley, Supervisor ____________________________________ Kamran Asdar Ali ____________________________________ Robert Fernea ____________________________________ Ward Keeler ____________________________________ Mark Nichter The Price of Passion: Performances of Consumption and Desire in the Philippine Go-Go Bar by Eric Alan Ratliff, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2003 Acknowledgements A project of this scope and duration does not progress very far without the assistance of many people. I would first like to acknowledge my dissertation committee members for their advice and encouragement over these many years. Douglas Foley, Ward Keeler, Robert Fernea, Kamran Ali and Mark Nichter provided constructive comments during those times when I could not find the right words and continuing motivation when my own patience and enthusiasm was waning. As with the subjects of my study, their ‘stories’ of ethnographic practice were both informative and entertaining at just the right moments. Many others have also offered inspiration and valuable suggestions over the years, including Eufracio Abaya, Laura Agustín, Priscilla Alexander, Dr. Nicolas Bautista, Katherine Frank, Jeanne Francis Illo, Geoff Manthey, Sachiyo Yamato, Aida Santos, Melbourne Tapper, and Kamala Visweswaran. This research would never have gotten off the ground without the support of the ReachOut AIDS Education Foundation (now ReachOut Foundation International). -

Thesis Finding Privacy in the Red-Light District

THESIS FINDING PRIVACY IN THE RED-LIGHT DISTRICT: AN ANALYSIS OF VICTORIAN ERA MEDICINE BOTTLES FROM THE VANOLI SITE (5OR.30) IN OURAY, COLORADO Submitted by Heather Horobik Department of Anthropology In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Fall 2011 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Mary Van Buren Ann Magennis Narda Robinson Copyright by Heather Horobik 2011 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT FINDING PRIVACY IN THE RED-LIGHT DISTRICT: AN ANALYSIS OF VICTORIAN ERA MEDICINE BOTTLES FROM THE VANOLI SITE (5OR.30) IN OURAY, COLORADO A sample of bottles from the Vanoli Site (5OR.30), part of a Victorian era red- light district in Ouray, Colorado are examined. Previous archaeological studies involving the pattern analysis of brothel and red-light district assemblages have revealed high frequencies of medicine bottles. The purpose of this project was to determine whether a sense of privacy regarding health existed and how it could influence disposal patterns. The quantity and type of medicine bottles excavated from two pairs of middens and privies were compared. A concept of privacy was discovered to have significantly affected the location and frequency of medicine bottle disposal. A greater percentage of medicine bottles was deposited in privies, the private locations, rather than the more visually open and accessible middens. This study concludes that, while higher percentages of medicine bottles are found within brothel and red-light district locations, other factors such as privacy and feature type may affect the artifact patterns associated with such sites. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people helped and supported me throughout the process involved in completing this thesis. -

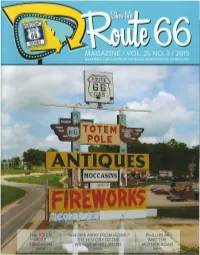

Volume 25, Number 3, 2015.Pdf

..~-•. "A HOME AWAY FROM HOME:" PHILLIRS, 66 THE HISTORY OF THE AND THE WA N WHEEL MOTEL MOTHER-ROAD- PAGE 20 Historic Route 66 stretches across the U.S. from Chicago to Los Angeles. Along the way, in Lebanon,Missouri is a growing popular landmark stop for any history enthusiast, tourist, or local Ozark resident. Shepherd Hills Factory Outlets started in the outlet business in 1972 as an outlet for locally made Walnut Bowls. Ida and Rea Reid, founders, began their entrepreneurship operating a motel in the 1960's called the Capri Motel which was located right along Route 66, known today as Interstate 44. ' They sold the Capri Motel in 1966 and along with their sons, Rod and Randy, started a new business in 1972 called the Shepherd Hills Gift Shop which was leased as a part of the Shepherd Hills Motel and happened to be located in virtually the same spot as the Capri Motel. Later, as they began expanding, they bought a portion of the motel as well as the gift shop and began construction of their current building in 1999. In the meantime, Shepherd Hills added additional locations including those in Osage Beach, MO, Branson, MO, and Eddyville, KY , and brought in other quality products to the lineup including Chicago Cutlery,Denby Pottery, and of course Case XX pocketknives--making the latter also available through catalog mail order and eventually on the web at www.CaseXX.com. MISSOURI us 66 contents IJiJt features 2 OFFICERS, BOARD OF DIRECTORS AND COMMITTEES 3 MEMBERSHIP MATTERS Robert Gehl 4 NEWS FROM THE ROAD 10 THE TOTEM POLE TRADITION -

Cowboy Chronicle February 2017 Page 1

Cowboy Chronicle February 2017 Page 1 VISIT US AT SASSNET .COM Cowboy Chronicle February 2017 Page 2 VISIT US AT SASSNET .COM Cowboy Chronicle The Cowboy February 2017 Page 3 Chronicle CONTENTS 4-7 COVER FEATURE Editorial Staff Canadian National Championships Skinny 8 FROM THE EDITOR Editor-in-Chief Skinny’s Soapbox Misty Moonshine 9-13 NEWS Riding for the Brand ... Palaver Pete Retiring Managing Editor 14, 15 LETTERS & OPINIONS Tex and Cat Ballou Editors Emeritus 16-19 COSTUMING CORNER Kudos to the Gentlemen of SASS Costuming Adobe Illustrator 20-31 ANNUAL REPORTS Layout & Design Hot Lead in Deadwood ... Range War 2016 Mac Daddy 32-37 GUNS & GEAR Dispatches From Camp Baylor Graphic Design 38-43 HISTORY Square Deal Jim A Botched Decade ... Little Known Famous People Advertising Manager 44-48 PROFILES (703) 764-5949 • Cell: (703) 728-0404 Scholarship Recipient 2016 ... Koocanusa Kid [email protected] 49 SASS AFFILIATED MERCHANTS LIST Staff Writers 50, 51 SASS MERCANTILE Big Dave, Capgun Kid Capt. George Baylor 52, 53 GENERAL STORE Col. Richard Dodge Jesse Wolf Hardin, Joe Fasthorse 54 ADVERTISER’S INDEX Larsen E. Pettifogger, Palaver Pete Tennessee Tall and Rio Drifter 55-61 ARTICLES Texas Flower My First Shoot ... Comic Book Corner Whooper Crane and the Missus 62, 63 SASS NEW MEMBERS The Cowboy Chronicle is published by 64 SASS AFFILIATED CLUB LISTINGS The Wild Bunch, Board of Directors of (Annual / Monthly) The Single Action Shooting Society. For advertising information and rates, administrative, and edi to rial offices contact: Chronicle Administrator 215 Cowboy Way • Edgewood, NM 87015 (505) 843-1320 • FAX (505) 843-1333 email: [email protected] Visit our Website at http://www.sassnet.com The Cowboy Chronicle SASSNET.COM i (ISSN 15399877) is published ® monthly by the Single Action Shooting Society, 215 SASS Trademarks Black River Bill ® ® Cowboy Way, Edgewood, NM 87015. -

Ludacris the Red Light District Full Album Zip

Ludacris, The Red Light District Full Album Zip ERROR_GETTING_IMAGES-1 Ludacris, The Red Light District Full Album Zip 1 / 2 Hood Starz.com].rar hosted on mediafire.com 80.48 MB, Ludacris Chicken N Beer ... Ludacris, The Red Light District Full ;Enoch; 17 videos; 147,667 views חנוך .(Album Zip Download.. Ludacris - The Red Light District (Full album + Bonus Track Last updated on Jun 26, 2015. Subscribe! Play all. Share.. Find Ludacris discography, albums and singles on AllMusic. ... The Red Light District. 2004. The Red Light District · Def Jam South · Disturbing tha Peace. 2005.. Tracklist: 1. Intro, 2. Number One Spot, 3. Get Back, 4. Put Your Money, 5. Blueberry Yum Yum, 6. Child Of The Night, 7. The Potion, 8. Pass Out, 9. Skit, 10.. 2000 - Ludacris - ''Back For The First Time''. Tracklist. 01. "U Got a Problem?" 02. .... 2004 - Ludacris - ''The Red Light District''. Tracklist. 01. "Intro" Timbaland. 02.. Ludacris – The Red Light District. The Red Light District (CD, Album) album cover. More Images · All Versions · Edit Release · Sell This ... Tracklist Hide Credits .... The red light district. ludacris 320 kbps . Ludacris release therapy itunes . tags ludacris the red light district. Ludacris, the red light district full album zip .... Ludacris - The Red Light District review: Inconsistent, but primarily ... Release Date: 2004 | Tracklist .... I haven't heard a full one after this. Calc. Ludacris – Chicken-N-Beer – Album Zip Quality: iTunes Plus AAC M4A ... songs lyrics, songs mp3 download, download zip and complete full album rar. ... DVD made by of Ludacris visiting the red-light district, a growroom, .... 4 Download zip, rar. -

Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II

Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II Volume 25 Article 1 2020 Full Issue Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/historical-perspectives Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation (2020) "Full Issue," Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II: Vol. 25 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/historical-perspectives/vol25/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. et al.: Full Issue Historical Perspectives Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History December 2020 Series II, Volume XXV ΦΑΘ Published by Scholar Commons, 2020 1 Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II, Vol. 25 [2020], Art. 1 Cover image: A birds world Nr.5 by Helmut Grill https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/historical-perspectives/vol25/iss1/1 2 et al.: Full Issue The Historical Perspectives Peer Review Process Historical Perspectives is a peer-reviewed publication of the History Department at Santa Clara University. It showcases student work that is selected for innovative research, theoretical sophistication, and elegant writing. Consequently, the caliber of submissions must be high to qualify for publication. Each year, two student editors and two faculty advisors evaluate the submissions. Assessment is conducted in several stages. An initial reading of submissions by the four editors and advisors establishes a short-list of top papers. -

Fang Family San Francisco Examiner Photograph Archive Negative Files, Circa 1930-2000, Circa 1930-2000

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/hb6t1nb85b No online items Finding Aid to the Fang family San Francisco examiner photograph archive negative files, circa 1930-2000, circa 1930-2000 Bancroft Library staff The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ © 2010 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Fang family San BANC PIC 2006.029--NEG 1 Francisco examiner photograph archive negative files, circa 1930-... Finding Aid to the Fang family San Francisco examiner photograph archive negative files, circa 1930-2000, circa 1930-2000 Collection number: BANC PIC 2006.029--NEG The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ Finding Aid Author(s): Bancroft Library staff Finding Aid Encoded By: GenX © 2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: Fang family San Francisco examiner photograph archive negative files Date (inclusive): circa 1930-2000 Collection Number: BANC PIC 2006.029--NEG Creator: San Francisco Examiner (Firm) Extent: 3,200 boxes (ca. 3,600,000 photographic negatives); safety film, nitrate film, and glass : various film sizes, chiefly 4 x 5 in. and 35mm. Repository: The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ Abstract: Local news photographs taken by staff of the Examiner, a major San Francisco daily newspaper. -

Wild West Photograph Collection

THE KANSAS CITY PUBLIC LIBRARY Wild West Photograph Collection This collection of images primarily relates to Western lore during the late 19th and parts of the 20th centuries. It includes cowboys and cowgirls, entertainment figures, venues as rodeos and Wild West shows, Indians, lawmen, outlaws and their gangs, as well as criminals including those involved in the Union Station Massacre. Descriptive Summary Creator: Brookings Montgomery Title: Wild West Photograph Collection Dates: circa 1880s-1960s Size: 4 boxes, 1 3/4 cubic feet Location: P2 Administrative Information Restriction on access: Unrestricted Terms governing use and reproduction: Most of the photographs in the collection are reproductions done by Mr. Montgomery of originals and copyright may be a factor in their use. Additional physical form available: Some of the photographs are available digitally from the library's website. Location of originals: Location of original photographs used by photographer for reproduction is unknown. Related sources and collections in other repositories: Ralph R. Doubleday Rodeo Photographs, Donald C. & Elizabeth Dickinson Research center, National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. See also "Ikua Purdy, Yakima Canutt, and Pete Knight: Frontier Traditions Among Pacific Basin Rodeo Cowboys, 1908-1937," Journal of the West, Vol. 45, No.2, Spring, 2006, p. 43-50. (Both Canutt and Knight are included in the collection inventory list.) Acquisition information: Primarily a purchase, circa 1960s. Citation note: Wild West Photograph Collection, Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, Missouri. Collection Description Biographical/historical note The Missouri Valley Room was established in 1960 after the Kansas City Public Library moved into its then new location at 12th and Oak in downtown Kansas City. -

The Murder of Donna Gentile: San Diego Policing and Prostitution 1980

THE MURDER OF DONNA GENTILE: SAN DIEGO POLICING AND PROSTITUTION 1980-1993 Jerry Kathleen Limberg Department of History California State University San Marcos © 2012 DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis to my husband, Andrew Limberg. Thank you for your love, encouragement, patience, support, and sacrifice through this endeavor. You have always supported me in my academic and professional goals, despite family and financial challenges. Your countless hours of reading drafts, reviewing film rough cuts, and listening to ideas are appreciated much more than you could possibly know. I also dedicate this thesis to my son Drew. Thank you for your love, hugs, and sacrifice. You are bright, creative, imaginative, caring, generous, inquisitive, and the best son any mother could ever hope for. Never stop asking, “Why?” Finally, I dedicate this thesis to my mom, Marlene Andrey. Thank you for years of love, support and encouragement. Without complaint, you allowed your teenage daughter to travel half away across the country to pursue her dreams out West. Whether you realize it or not, you provided me with the tools and skills to succeed. THESIS ABSTRACT Donna Gentile, a young San Diego prostitute who had been a police corruption informant was murdered in June, 1985. Her murder occurred approximately a month after she testified in a civil service hearing involving two San Diego police officers, Officer Larry Avrech and Lieutenant Carl Black. The hearing occurred approximately four months after Avrech was fired from the police department and Black was demoted for their involvement with Gentile. Looming over the San Diego community was public speculation that Gentile’s killer was a police officer. -

Murder and Morality: Late Nineteenth-Century Protestants’ Reaction to the Murder of Helen Jewett

University of Mary Washington Eagle Scholar Student Research Submissions Spring 5-6-2021 Murder and Morality: Late Nineteenth-Century Protestants’ Reaction to the Murder of Helen Jewett Grace Corkran Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Corkran, Grace, "Murder and Morality: Late Nineteenth-Century Protestants’ Reaction to the Murder of Helen Jewett" (2021). Student Research Submissions. 400. https://scholar.umw.edu/student_research/400 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by Eagle Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research Submissions by an authorized administrator of Eagle Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Murder and Morality: Late Nineteenth-Century Protestants’ Reaction to the Murder of Helen Jewett Grace Corkran Religious Studies 401: Guided Research March 5, 2021 Corkran, 2 In 1836, Richard Robinson murdered Helen Jewett, a former domestic servant from Maine working as a prostitute in New York. Jewett’s death captivated the nation as newspapers and pamphlets detailed accounts of her seduction, fall from society, and life as a sex worker. The sensational stories about Jewett’s early life were of particular interest for audiences wondering how a girl, who lived and worked in a prominent Protestant family household, could willingly choose to become a prostitute. George Wilkes created a novelization of Helen Jewett’s life in 1878, which created a public image of Jewett -

1 a Preservationist's Guide to the Harems, Seraglios, and Houses of Love of Manhattan: the 19Th Century New York City Brothel In

1 A Preservationist's Guide to the Harems, Seraglios, and Houses of Love of Manhattan: The 19th Century New York City Brothel in Two Neighborhoods Angela Serratore Advisor: Ward Dennis Readers: Chris Neville, Jay Shockley Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Science in Historic Preservation Graduate School of Architecture,Planning,and Preservation Columbia University May 2013 2 Table of Contents 2 Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 4 Part I: History Brothel History 8 Neighborhood Histories 45 Part II: Interpretation Theoretical Challenges 60 Site-Specific Challenges/Case Studies 70 Conclusions 97 Appendices Interpretive Methods 99 Additional Maps and Photos 116 3 Acknowledgements Profuse thanks to my advisor, Ward Dennis, who shepherded this project on its journey from half-formed idea into something legible, productive, and fun to write. I'm also indebted to my readers, Chris Neville and Jay Shockley, for getting as excited about this project as I've been. The staff at the New York Historical Society let me examine a brothel guidebook that hadn't yet been catalogued, which was truly thrilling. Jacqueline Shine, Natasha Vargas-Cooper, and Michelle Legro listened patiently as I talked about 19th century prostitution without complaint. My classmates Jonathan Taylor and Amanda Mullens did the same. The entire staff of Lapham's Quarterly picked up the slack when I was off looking for treasure at various archives. My parents, Peter Serratore and Gina Giambalvo-Glockler, let me fly to their houses to write, in two much-needed escapes from New York. They also proudly tell friends and colleagues all about this thesis without blushing, for which I will always be grateful.