Download Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Audible Pasts: History, Sound and Human Experience in Southeast Asia1

KEMANUSIAAN Vol. 25, Supp. 1, (2018), 1–19 Audible Pasts: History, Sound and Human Experience in Southeast Asia1 BARBARA WATSON ANDAYA Asian Studies Program, University of Hawai‘i, 1890 East West Road, Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96822, USA [email protected] Published online: 20 December 2018 To cite this article: Andaya, B.W. 2018. Audible pasts: History, sound and human experience in Southeast Asia. KEMANUSIAAN the Asian Journal of Humanities 25(Supp. 1): 1–19, https://doi.org/10.21315/kajh2018.25.s1.1 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.21315/kajh2018.25.s1.1 Abstract. Although historians of traditional Southeast Asian cultures rely primarily on written sources, the societies they study were intensely oral and aural. Research on sound in Southeast Asia has focused on music and musicology, but historians are now considering the wide variety of noises to which people were exposed, and how the interpretations and understanding of these sounds shaped human experience. This article uses an 1899 court case in Singapore concerning a noisy neighbour as a departure point to consider some of the ways in which “noise” was heard in traditional Southeast Asian societies. Focusing on Singapore, it shows that European attitudes influenced the attitudes of the colonial administration towards loud noise, especially in the streets. By the late 19th century, the view that sleep was necessary for good health, and that noise interfered with sleep, was well established. The changing soundscape of Singapore in the early 20th century led to increasing middle class demands for government action to limit urban noise, although these were largely ineffective. -

Battle Against the Bug Asia’S Ght to Contain Covid-19

Malaysia’s political turmoil Rohingyas’ grim future Parasite’s Oscar win MCI(P) 087/05/2019 Best New Print Product and Best News Brand in Asia-Pacic, International News Media Association (INMA) Global Media Awards 2019 Battle against the bug Asia’s ght to contain Covid-19 Countries race against time to contain the spread of coronavirus infections as fears mount of further escalation, with no sign of a vaccine or cure yet WE BRING YOU SINGAPORE AND THE WORLD UP TO DATE IN THE KNOW News | Live blog | Mobile pushes Web specials | Newsletters | Microsites WhatsApp | SMS Special Features IN THE LOOP ON THE WATCH Facebook | Twitter | Instagram Videos | FB live | Live streams To subscribe to the free newsletters, go to str.sg/newsletters All newsletters connect you to stories on our straitstimes.com website. Data Digest Bats: furry friends or calamitous carriers? SUPPOSEDLY ORIGINATING IN THE HUANAN WHOLESALE On Jan 23, a team led by coronavirus specialist Shi Zheng-Li at Seafood Market in Wuhan, the deadly Covid-19 outbreak has the Wuhan Institute of Virology, reported on life science archive opened a pandora’s box around the trade of illegal wildlife and bioRxiv that the Covid-19 sequence was 96.2 per cent similar to the sale of exotic animals. a bat virus and had 79.5 per cent similarity to the coronavirus Live wolf pups, civets, hedgehogs, salamanders and crocodiles that caused severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars). were among many listed on an inventory at one of the market’s Further findings in the Chinese Medical Journal also discovered shops, said The Guardian newspaper. -

The Straits Times, U, and a 40 Per Cent Stake in Mediacorp Press Limited, the Business Times, the New Paper, Berita Harian, Which Publishes the Free Newspaper, Today

MEDIASCAPE Maintaining Focus in an Evolving Mediascape Annual Report 2016 CONTENTS 01 26 61 70 Corporate Further Information on Daily Average Corporate Profile Board of Directors Newspapers Circulation Information 02 30 62 71 Businesses and Products Senior Financial Sustainability under the SPH Group Management Review Report 14 38 65 76 Organisation CEO’s Overview of Group Value Added Corporate Governance Structure Operations Statement Report 15 50 66 96 Group Financial Significant Investor Risk Highlights Events Relations Management 16 56 68 113 Chairman’s Awards & Investor Financial Statement Accolades Reference Contents 20 60 Board of SPH Newspapers Directors Readership Trends Singapore Press Holdings Annual Report 2016 CORPORATE PROFILE INCORPORATED IN 1984, MAIN BOARD-LISTED SINGAPORE PRESS HOLDINGS LTD (SPH) IS ASIA’S LEADING MEDIA ORGANISATION, ENGAGING MINDS AND ENRICHING LIVES ACROSS MULTIPLE LANGUAGES AND PLATFORMS. Media SPH has a 20 per cent stake in MediaCorp TV Holdings The English/Malay/Tamil Media group comprises Pte Ltd, which operates free-to-air channels 5, 8 and the print and digital operations of The Straits Times, U, and a 40 per cent stake in MediaCorp Press Limited, The Business Times, The New Paper, Berita Harian, which publishes the free newspaper, Today. and their respective student publications. It also includes subsidiaries Tamil Murasu Ltd, which publishes Properties Tamil Murasu and tabla!; book publishing arm Straits SPH REIT is a Singapore-based REIT established to Times Press; SPH Data Services, which licenses the invest in a portfolio of income-producing real estate use of the Straits Times Index in partnership with the primarily for retail purposes. -

Building for Tomorrow

Thai cave rescue Interview with Moon Jae-in Summit city, Singapore MCI(P) 096/08/2017 FebruaryAugust – September- MCI(P)March 096/08/2017 2018 2018 INDEPENDENT • INSIDER • INSIGHTS ON ASIA Smart Cities: Building for Tomorrow A global push to build smart cities is on with policy makers and shapers scouting for the best technology solutions to allow people to enjoy their living and working spaces. Thai cave rescue Interview with Moon Jae-in Summit city, Singapore MCI(P) 096/08/2017 FebruaryAugust – September- MCI(P)March 096/08/2017 2018 2018 INDEPENDENT • INSIDER • INSIGHTS ON ASIA Contents Smart Cities: Building for Tomorrow A global push to build smart cities is on with policy makers and shapers scouting for the best technology solutions to allow people to enjoy their living and working spaces. 2 Getting smarter for the future 5 Rise of Asian Smart Cities Asia Report August – September 2018 CHINA: Yinchuan leads the way in using tech to improve daily life JAPAN: Small but smart cities woo business and young talent Warren Fernandez Editor-in-Chief, The Straits Times & SPH’s English, Malay and 8 Smart City Mayors: Mayor, West Java governor... Indonesia’s Tamil Media (EMTM) Group president in 2024? Sumiko Tan 11 A network of smart cities Managing Editor, EMTM & Executive Editor, The Straits Times 13 Cooling Singapore project comes up with new ways Tan Ooi Boon to beat the heat Senior Vice-President (Business Development), EMTM 15 Cheers! A special beer to mark a special anniversary Paul Jacob Associate Editor, The Straits Times 16 Thailand -

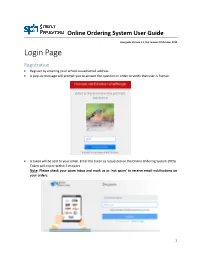

Login Page Registration Register by Entering Your School-Issued Email Address

Online Ordering System User Guide User guide Version 1.1, last revised: 22 October 2018 Login Page Registration Register by entering your school-issued email address. A pop-up message will prompt you to answer the question in order to verify that user is human. A token will be sent to your email. Enter the token as requested on the Online Ordering System (OOS). Token will expire within 5 minutes. Note: Please check your spam inbox and mark us as ‘not spam’ to receive email notifications on your orders. 1 Once token is successfully entered, user will be directed to the registration page to fill up details. Select your school and enter details – DID, Fax and Password. Password Requirements: o Exactly 8 alphanumeric characters o At least 1 lowercase o At least 1 uppercase o At least 1 number User will see the message below when they have successfully registered. 2 Login Users will be required to log in with their Email Address and Password. Reset Password If users forget their password, click “Forgot password” and enter your email address. A token code will be sent to your email. The token will expire within 5 minutes. User will then be prompted to enter their new password. 3 Dashboard My Dashboard Upon logging in, users are taken to the homepage – My Dashboard. Users can navigate using the tabs on the top right bar: On ‘My Dashboard’, users will be able to view the following: 1. Order Summary My Pending Orders: Users can save their orders as drafts and continue pending orders by clicking on the green arrow. -

2019 Award Winners

2019 award winners Eighteen awards were presented to celebrate and honour the best works of journalists across newsrooms at the English/Malay/Tamil Media Group’s Annual Awards yesterday. Here are the award winners. YOUNG JOURNALIST Tee Zhuo STORY OF Senior Health Correspondent Salma Khalik for her story JOURNALIST Joyce Lim OF THE YEAR The Straits Times THE YEAR “The puzzling case of SMC’s judgment on a doctor who OF THE YEAR The Straits Times was ned $100,000” (The Straits Times, Feb 7, 2019) EXCELLENCE IN JOURNALISM Claire Huang, Elizabeth Law, Chong Celestino Gulapa D Rosario for his Rodolfo Carlos Pazos, Alyssa Karla Anita Gabriel for her story “It’s 1 Jun Liang, Trixia Carungcong, Spe 3 infographics “20 on Rafes” 7 Mungcal, Lee Pei Jie, Chee Wei Xian, 13 switch and save as SP powers up Chen, Lee Pei Jie, Chee Wei Xian, Lim (The Straits Times, Dec 21, 2019) Tin May Linn, Thong Yong Jun, Denise S$1.30 householdsA SINGAPORE PRESS HOLDINGS PUBLICATION | businesstimes.c om.swithg | fb.com/thebusinesstimes cheaper | @BusinessTimes | CO REGN NO 198402868 Eoption” | MCI (P) 048/12/2018 Tuesday, October 29, 2019 Yaohui, Philip Cheong, Rodolfo Pazos, Chong, Melody Zaccheus, Tee Zhuo, (The Business Times, Oct 29, 2019) Tin May Linn & Jamie Koh for their Benjamin Seetor, Lim Yaohui, Samuel D6 life home and garden | THE STRAITS TIMES | SATURDAY, DECEMBER 21, 2019 | MARKETS Monday Change cross media stories & video: RAFFLES PITCHER PLANT Ruby, Azim Azman, Yeung E-von, STI Closed A lover of the natural world, 11 KL COMP Closed Rafes employed zoologists and It’s switch and save as SP powers up botanists to discover exotic NIKKEI 225 22,867.27 +67.46 species found in the region. -

Awards & Accolades

awards & accolades Corporate Governance Awards Other Corporate Awards 1. Singapore Corporate Awards 1. Supporter of MINDS Award • Best Investor Relations Award (Silver, $1 billion and above market capitalisation category) 2. Singapore HR Awards 2012 • Corporate HR Champion 2. 12th SIAS Investors’ Choice Awards 2011 • Corporate HR Award • Runner Up - Most Transparent Company Award 2011 • Leading HR Practices Category (Non-Electronics Manufacturing Category) – Learning & Human Capital Development • Financial Journalist of the Year – HR Communications and Branding (The Business Times, Ms Lynette Khoo) – E-HR Management (Special Mention) • Financial Story of the Year • Special Category (The Business Times, Ms Felda Chay) – Corporate Social Responsibility • Promising Journalist of the Year – Fair Employment Practices (The Straits Times, Ms Esther Teo) • Promising Journalist of the Year (The Business Times, Ms Joyce Hooi) 3. Community Chest Awards • Investor Education Journalist of the Year • Corporate Platinum Award (The Business Times, Ms Teh Hooi Ling) 4. Patron of Heritage Awards • SPH received Partner of Heritage award 5. Total Defence Awards 2012 • Total Defence Awards (Employers) – 2nd Tier: Distinguished Defence Partner Award 6. SCDF Strategic Partner Award 2012 Singapore Corporate Awards Patron of the Arts Award 52 awards & accolades 7. Brand Finance Forum 2012 – 4. Digital Media of the Year Awards by Marketing Top 100 Most Valuable Brand Magazine • SPH (13th position) • Women Category • The Straits Times (50th position) – 1st – herworldPLUS (www.herworldPLUS.com) • Her World (75th position) • Men Category • Lianhe Zaobao (78th position) – 1st – Men’s Health (www.menshealth.com.sg) • Nuyou (86th position) • Tech Category – 1st – HardwareZone (www.HardwareZone.com) • Luxury Category 8. Patron of the Arts Award – 1st – Luxury Insider (www.Luxury-Insider.com) • SPH received Distinguished Patron of the Arts award • Business & Finance Category for the 20th consecutive year. -

Challenges of Digitizing Vernacular Newspapers & Preliminary Study Of

Challenges of Digitizing Vernacular Newspapers & Preliminary Study of User Behaviour on NewspaperSG’s Multilingual UI Mazelan bin Anuar, Cally Law and Soh Wai Yee Abstract Singapore is a multicultural nation. About 76 per cent of Singapore’s population is ethnically Chinese, 14 per cent Malay, nine per cent Indian and the rest comprising other ethnic groups. Borne out of a pragmatic need to operate in the global economy using the English language, Singapore adopted the bilingual education policy in 1966. As a result, the majority of the Singaporean citizens are bilingual today, able to communicate effectively in English and their mother tongues. Four official languages are used in Singapore, namely English, Mandarin, Malay and Tamil. NewspaperSG is an online resource of Singapore newspapers published from 1831 to 2009. It was started in March 2009 with one major newspaper title in English, namely the Straits Times. Its coverage has now expanded to 29 titles, including Chinese, Malay and Tamil newspapers. With the introduction of these newspapers since August 2011, the multilingual interface was introduced in NewspaperSG to allow users to navigate the portal in English, Chinese or Malay. The paper will highlight the process and challenges that the team faced during the digitization of the multilingual newspapers, especially newspapers in the Chinese language. It will also present the preliminary findings on the study of user behaviour in NewspaperSG’s multilingual environment. Introduction Singapore was opened as a British trading post in 1819. Its first newspaper, Singapore Chronicle and Commercial Register, started in 1824. Since then more than 120 newspapers had been published in Singapore but many of them were short-lived and had ceased publication. -

Corporate Profile

CORPORATE PROFILE Singapore Press Holdings (SPH) is Southeast Asia’s leading media 40 per cent stake in MediaCorp Press Ltd, which publishes the organisation, engaging minds and enriching lives across multiple free newspaper, Today. languages and platforms. SPH’s events subsidiary Sphere Exhibits organises innovative SPH has 19 titles licensed under the Newspaper Printing and consumer and trade events and exhibitions as well as large scale Presses Act, of which nine are daily newspapers across four conferences. SPH also has a leading digital out-of-home platform languages. Every day, 3.05 million individuals or 76 per cent called SPHMBO, comprising a network of large outdoor LED of people above 15 years old, read one of our publications. billboards at strategic locations (e.g. Raffles Place, Orchard Road etc) and indoor screens across shopping centres and banks island- The online editions of our main newspapers enjoy over wide. It also operates large format billboards, banners and other 300 million page views with 20 million unique visitors static media platforms. every month. Straits Times Press, SPH’s book-publishing arm, as well as Focus Our success is built on the long history and rich heritage of Publishing, produce quality books and periodicals in English our two flagship newspapers – The Straits Times, the English- and Chinese. language daily and Lianhe Zaobao, the Chinese-language daily. The other two dailies, Berita Harian and Tamil Murasu, SPH REIT was successfully listed on 24 July 2013. SPH REIT is remain the staple for the Malay-speaking and Tamil-speaking a Singapore-based REIT established principally to invest, directly communities respectively. -

CONTENTS Updated December 2011

CONTENTS Updated December 2011 ON PRINT The Straits Times 3 The Sunday Times 4 The Business Times/The Business Times Weekend 5 The New Paper/The New Paper Sunday 6 Lianhe Zaobao 7 Lianhe Wanbao 8 Shin Min Daily News 9 Thumbs Up / Thumbs Up Junior 9 my paper 10 Tabla! 10 Berita Harian 11 Berita Minggu 11 Tamil Murasu 12 Hybrite/Coloured Newsprint 13 Out-of-Print 13 Specifications 14 Easy Calculations 16 Rates Of Common Ad Sizes 17 Master Contract Privileges — Volume Discount Structure 22 Master Contract Privileges 22 Terms And Conditions 26 Miscellaneous Charges 32 Conditions For Joint Rate And Int’l Edition Bookings 32 Deadlines For Electronic Copy 33 Copy Deadlines – Others 34 Cancellation Deadlines 36 37 SPH magazines 37 ONLINE Online Display 39 Online Classified 44 ON MOBILE Mobile Marketing 45 Mobile App Banners 46 ON SCREEN Out-Of-Home 47 ON GROUND Event Management/Exhibitions 47 ON AIR Radio 48 1 2 Digital Life (Wednesday) Mind Your Body (Thursday) NEWSPAPER Urban (Friday) Base Rate and Colour Surcharges Similar to The Straits Times Premiums Front Page ...................................................................................................... 35% Back Page ...................................................................................................... 20% DISPLAY Other specified pages/positions .................................................................... 15% Page 2 ............................................................................................................ 15% Base Rate Mon-Wed Thur-Fri Sat -

Introduction to Singapore Press Holdings

Introduction to Singapore Press Holdings Updated on March 2014 23 May 07 1 Frequently Asked Questions Reference slide no. 1. Why is SPH dominant in the Singapore media industry? 3 – 4 2. Who are the controlling shareholders of SPH and what is their 5 stake? 3. Newspaper circulation is falling globally. What is SPH doing 6 - 7 about declining circulation? 4. Is SPH’s newspaper business affected by the Internet and other 8 - 9 media? 5. What are the growth areas of the Group? Will SPH expand 10 -14 overseas? 6. What is the Group’s property strategy? 15 - 18 7. What is SPH’s operating margin and is it sustainable? 19 8. What is SPH’s dividend policy? 20 2 A Leading Media Organisation Newspapers Dominant Newspaper Broadcasting Publisher in Singapore Magazines Leading Magazine 3 radio stations and 20% Publisher in stake in free-to-air TV Singapore & Malaysia Events and SPH New Media Exhibitions News portals, Consumer and Online classifieds trade events Property Investments -Approx. S$1.7b of investible funds - SPH REIT (70%) including MobileOne (13.9%) - The Seletar Mall , & Starhub (0.8%) under construction (70%) 3 Dominant Newspaper Publisher in Singapore SPH has a spectrum of products including the 168-year-old English flagship daily, The Straits Times, and the 90-year-old Chinese daily, Lianhe Zaobao. SPH publishes 19 out of 20* licensed newspapers in Singapore In Singapore, # 76% of population above newspapers has 15 years old read one more than 50%^ of SPH’s news share of the media ad publications daily market * SPH also has a 40% stake in Today – a freesheet by MediaCorp # Source: Nielsen 4 ^ Source: SPH SPH Shareholdings . -

Singapore's SPH Sues Yahoo! in Copyright Row 23 November 2011

Singapore's SPH sues Yahoo! in copyright row 23 November 2011 "This matter has been referred to our legal advisors and as such we are unable to comment further at this time." Asian media firm Singapore Press Holdings is suing Yahoo! for copyright infringement, accusing the US Internet giant of reproducing its news items without permission, both firms confirmed Wednesday. A front-page report on its flagship Straits Times newspaper said SPH had asked Singapore's High Court Asian media group Singapore Press Holdings is to stop Yahoo! from further reproducing its articles and suing Yahoo! for copyright infringement, accusing pay unspecified damages for infringement. the US Internet giant of reproducing its news items without permission. SPH, publisher of the Straits Times newspaper and In a story on the Yahoo! Singapore website, the other dailies, has asked Singapore's High Court to California-based firm's Southeast Asia Managing stop Yahoo! from further reproducing articles from Editor Alan Soon said: "We intend to vigorously its newspapers and pay unspecified damages for defend ourselves against this suit. infringement. "Our editorial business model of acquired, "In our statement of claim, we cited, as examples, commissioned and original content is proven." 23 articles from our newspapers which Yahoo! had reproduced over a 12-month period without our The Straits Times said that despite a request to licence or authorisation," SPH spokeswoman Chin cease the alleged infringement, "substantial Soo Fang told AFP. reproduction" of SPH content continued to be available on Yahoo! Southeast Asia's sites. According to a story on the front page of the Straits Times, they included political and crime stories that SPH is asking the court to declare that Yahoo! were first published in the print editions of the Southeast Asia infringed on its copyright, stop it Straits Times, The New Paper and My Paper.