John Muir (1838-1914)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{Osemite Nature Notes F Di.Ljme Xxxvii - Number 12 December 1958 Nationai Park R Service

{OSEMITE NATURE NOTES F DI.LJME XXXVII - NUMBER 12 DECEMBER 1958 NATIONAI PARK R SERVICE IN COOPERATION WITH THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE . —Anderson NPC Organized cross-country skiing is an excellent way to enjoy the winter beauty of Yosemite's high country . in its 37th year of public service. The YOSEMITE monthly publication of Yosemite 's park naturalists and the Yosemite Natural Nature Notes History Association. John C . Preston, Superintendent D . H . Hubbard, Park Naturalist Robert F . Upton, Assoc . Park Naturalist P . F . McCrary, Asst . Park Naturalist S . J . Zachwieja, Junior Park Naturalist Robert A . Groin, Park Naturalist Trainee VOL . XXXVII DECEMBER 1958 NO . 12 TIOGA PEAK By William Neely, Ranger-Naturalist P When climbing our Tuolumne Glaciers have never been up here. mountains it is difficult to remember During glacial ages the ice gathered that they have not been pushed up in hollows on slopes and ground their individually, but rather that they way down valleys . The mountain are remnants of flat land that has tops, if high enough, were spared been cut away. Here we hike much and stood above the Tuolumne ice of the time in glacier-scoured, glacier- field as isolated peaks or nunataks, worn, glacier-sculptured topography being gnawed away on all sides. and see the new surfaces, the work Cockscomb and Cathedral peaks are of ice chisels and ice tools, the signs of action and tremendous grinding the spiry fragments of once fatter . The ice, working easily forces. But there is that region above mountains that is untouched by glacier work, a in the vertical joint planes and cracks quiet and ancient region . -

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK O C Y Lu H M Tioga Pass Entrance 9945Ft C Glen Aulin K T Ne Ee 3031M E R Hetc C Gaylor Lakes R H H Tioga Road Closed

123456789 il 395 ra T Dorothy Lake t s A Bond C re A Pass S KE LA c i f i c IN a TW P Tower Peak Barney STANISLAUS NATIONAL FOREST Mary Lake Lake Buckeye Pass Twin Lakes 9572ft EMIGRANT WILDERNESS 2917m k H e O e O r N V C O E Y R TOIYABE NATIONAL FOREST N Peeler B A Lake Crown B C Lake Haystack k Peak e e S Tilden r AW W Schofield C TO Rock Island OTH IL Peak Lake RI Pass DG D Styx E ER s Matterhorn Pass l l Peak N a Slide E Otter F a Mountain S Lake ri e S h Burro c D n Pass Many Island Richardson Peak a L Lake 9877ft R (summer only) IE 3010m F LE Whorl Wilma Lake k B Mountain e B e r U N Virginia Pass C T O Virginia S Y N Peak O N Y A Summit s N e k C k Lake k c A e a C i C e L C r N r Kibbie d YO N C n N CA Lake e ACK AI RRICK K J M KE ia in g IN ir A r V T e l N k l U e e pi N O r C S O M Y Lundy Lake L Piute Mountain N L te I 10541ft iu A T P L C I 3213m T Smedberg k (summer only) Lake e k re e C re Benson Benson C ek re Lake Lake Pass C Vernon Creek Mount k r e o Gibson e abe Upper an r Volunteer McC le Laurel C McCabe E Peak rn Lake u Lake N t M e cCa R R be D R A Lak D NO k Rodgers O I es e PLEASANT EA H N EL e Lake I r l Frog VALLEY R i E k G K C E LA e R a e T I r r Table Lake V North Peak T T C N Pettit Peak A INYO NATIONAL FOREST O 10788ft s Y 3288m M t ll N Fa s Roosevelt ia A e Mount Conness TILT r r Lake Saddlebag ILL VALLEY e C 12590ft (summer only) h C Lake ill c 3837m Lake Eleanor ilt n Wapama Falls T a (summer only) N S R I Virginia c A R i T Lake f N E i MIGUEL U G c HETCHY Rancheria Falls O N Highway 120 D a MEADOW -

Talk 8 at State Episode 8: Getting Outside with Abby Hepp Transcript

Talk 8 at State Episode 8: Getting Outside with Abby Hepp Transcript Eliza Barsanti: Welcome to the department of Health and Exercise Studies’ Talk 8 at State Podcast with your host, Eliza Barsanti! EB: A couple weeks into the Fall 2020 semester, Covid-19 precautions caused NC State to put all classes online. This switch caused a lot of change in the lives of NC State students, forcing them to step out of their typical day-to-day routines in favor of something different. Abby Hepp ‘23 took this as an opportunity to go on the adventure of a lifetime-hiking, camping, and climbing her way across the United States! Today, we sit down with her to talk about her cross-country road trip, along with advice and NC State resources that students can use to get outside and craft their own adventures. EB: Okay, so today we are sitting down with Abby Hepp. Abby, would you like to introduce yourself to the podcast? Abby Hepp: Hi my name is Abby Hepp, I am majoring in Communication Media at NC State and I'm currently a sophomore. EB: Awesome! So we're going to get right into it! Today we're going to be talking about some of your adventures that you've been going on in the past few years and using to inspire other people as well, so let's start with- how did you become involved in outdoor activities and adventuring initially? AH: First of all, thank you for having me and initially will growing up, I would say my family was moderately active and you know I kind of had the typical playing outside with the neighbors childhood. -

2018 Spring WTC Newsletter

Vol. 29, No. 1 / Spring 2018 Blood, Sweat and Ink on the PCT (pg. 2) Is This the End? (pg. 5) Adventure in Your Own Backyard (pg. 6) Experience Trips: You Want Them, We’ve Got Them! (pg. 12) Shawnté Salabert, guidebook author and WTC instructor, on the Pacific Crest Trail WTC OFFICERS Contents (see your Student Handbook for contact information) WTC Chair WTC Outings Co-Chairs Bob Myers Adrienne Benedict Tom McDonnell WTC Registrar FEATURES Jim Martins LONG BEACH/SOUTH BAY SAN GABRIEL VALLEY Smiles, Not Miles Area Chair Area Chair Writer and WTC-instructor Shawnté Salabert spent 2 Brian Decker Jeremy Netka more than two years writing the guidebook on Area Vice Chair Area Vice Chair section hiking the southern section of the Pacific Sharon Moore Jan Marie Perry Crest Trail—and she’s got some advice for you. Area Trips Area Trips Mike Adams Mat Kelliher Is This the End? Spoiler alert—no, it isn’t! Lubna Debbini and Victor 5 Area Registrar Area Registrar Joan Rosenburg Amy Smith Gomez point you down the road of post-WTC fun and adventure. ORANGE COUNTY WEST LOS ANGELES Area Chair Area Chair Adventure in Your Own Backyard Matt Hengst Pamela Sivula Ditch the long drive—in Southern California 6 Area Vice Chair Area Vice Chair there’s adventure right out the back door and Gary McCoppin Katerina Leong Will McWhinney has a few ideas. Area Trips Area Trips Matt Hengst Adrienne Benedict Alphabet Soup Dig into the Angeles Chapter’s sections and you 8 Area Registrar Area Registrar find plenty of outdoor and other possibilities— Wendy Miller Pamela Sivula and acronyms. -

Upper Tuolumne River: Available Data Sources, Field Work Plan, and Initial Hydrology Analysis

Upper Tuolumne River: Available Data Sources, Field Work Plan, and Initial Hydrology Analysis water hetch hetchy water & power clean water October 2006 Upper Tuolumne River: Available Data Sources, Field Work Plan, and Initial Hydrology Analysis Final Report Prepared by: RMC Water and Environment and McBain & Trush, Inc. October 2006 Upper Tuolumne River Section 1 Introduction Available Data Sources, Field Work Plan, and Initial Hydrology Analysis Table of Contents Section 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 Section 2 Hetch Hetchy Facilities in the Study Area ............................................................. 4 Section 3 Preliminary Analysis of the Effects of Hetch Hetchy Project Facilities and Operations on Flow in Study Reaches ..................................................................................... 7 3.1 Analysis Approach ..................................................................................................... 7 3.2 The Natural Hydrograph........................................................................................... 10 3.3 Effects of Flow Regulation on Annual Hydrograph Components ............................. 12 3.3.1 Cherry and Eleanor Creeks.................................................................................................... 14 3.3.2 Tuolumne River...................................................................................................................... 17 3.4 Effects -

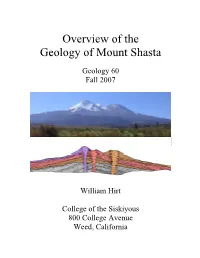

Overview of the Geology of Mount Shasta

Overview of the Geology of Mount Shasta Geology 60 Fall 2007 William Hirt College of the Siskiyous 800 College Avenue Weed, California Introduction Mount Shasta is one of the twenty or so large volcanic peaks that dominate the High Cascade Range of the Pacific Northwest. These isolated peaks and the hundreds of smaller vents that are scattered between them lie about 200 kilometers east of the coast and trend southward from Mount Garibaldi in British Columbia to Lassen Peak in northern California (Figure 1). Mount Shasta stands near the southern end of the Cascades, about 65 kilometers south of the Oregon border. It is a prominent landmark not only because its summit stands at an elevation of 4,317 meters (14,162 feet), but also because its volume of nearly 500 cubic kilometers makes it the largest of the Cascade STRATOVOLCANOES (Christiansen and Miller, 1989). Figure 1: Locations of the major High Cascade volcanoes and their lavas shown in relation to plate boundaries in the Pacific Northwest. Full arrows indicate spreading directions on divergent boundaries, and half arrows indicate directions of relative motion on shear boundaries. The outcrop pattern of High Cascade volcanic rocks is taken from McBirney and White (1982), and plate boundary locations are from Guffanti and Weaver (1988). Mount Shasta's prominence and obvious volcanic character reflect the recency of its activity. Although the present stratocone has been active intermittently during the past quarter of a million years, two of its four major eruptive episodes have occurred since large glaciers retreated from its slopes at the end of the PLEISTOCENE EPOCH, only 10,000 to 12,000 years ago (Christiansen, 1985). -

Yosemite National Park Foundation Overview

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Yosemite National Park California Contact Information For more information about Yosemite National Park, Call (209) 372-0200 (then dial 3 then 5) or write to: Public Information Office, P.O. Box 577, Yosemite, CA 95389 Park Description Through a rich history of conservation, the spectacular The geology of the Yosemite area is characterized by granitic natural and cultural features of Yosemite National Park rocks and remnants of older rock. About 10 million years have been protected over time. The conservation ethics and ago, the Sierra Nevada was uplifted and then tilted to form its policies rooted at Yosemite National Park were central to the relatively gentle western slopes and the more dramatic eastern development of the national park idea. First, Galen Clark and slopes. The uplift increased the steepness of stream and river others lobbied to protect Yosemite Valley from development, beds, resulting in formation of deep, narrow canyons. About ultimately leading to President Abraham Lincoln’s signing 1 million years ago, snow and ice accumulated, forming glaciers the Yosemite Grant in 1864. The Yosemite Grant granted the at the high elevations that moved down the river valleys. Ice Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove of Big Trees to the State thickness in Yosemite Valley may have reached 4,000 feet during of California stipulating that these lands “be held for public the early glacial episode. The downslope movement of the ice use, resort, and recreation… inalienable for all time.” Later, masses cut and sculpted the U-shaped valley that attracts so John Muir led a successful movement to establish a larger many visitors to its scenic vistas today. -

Matthew Greene Were Starting to Understand the Grave the Following Day

VANISHED An account of the mysterious disappearance of a climber in the Sierra Nevada BY MONICA PRELLE ILLUSTRATIONS BY BRETT AFFRUNTI CLIMBING.COM — 61 VANISHED Three months earlier in July, the 39-year-old high school feasted on their arms. They went hiking together often, N THE SMALL SKI TOWN of Mammoth Lakes in math teacher dropped his car off at a Mammoth auto shop even in the really cold winters common to the Northeast. California’s Eastern Sierra, the first snowfall of the for repairs. He was visiting the area for a summer climb- “The ice didn’t slow him down one bit,” Minto said. “I strug- ing vacation when the car blew a head gasket. The friends gled to keep up.” Greene loved to run, competing on the track year is usually a beautiful and joyous celebration. Greene was traveling with headed home as scheduled, and team in high school and running the Boston Marathon a few Greene planned to drive to Colorado to join other friends times as an adult. As the student speaker for his high school But for the family and friends of a missing for more climbing as soon as his car was ready. graduation, Greene urged his classmates to take chances. IPennsylvania man, the falling flakes in early October “I may have to spend the rest of my life here in Mam- “The time has come to fulfill our current goals and to set moth,” he texted to a friend as he got more and more frus- new ones to be conquered later,” he said in his speech. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Historica Olomucensia 53-2017

HISTORICA OLOMUCENSIA 53–2017 SBORNÍK PRACÍ HISTORICKÝCH XLIII HISTORICA OLOMUCENSIA 53–2017 Sborník prací historických XLIII Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci Olomouc 2017 Zpracování a vydání publikace bylo umožněno díky fi nanční podpoře, udělené roku 2017 Ministerstvem školství, mládeže a tělovýchovy ČR v rámci Institucionálního roz- vojového plánu, Filozofi cké fakultě Univerzity Palackého v Olomouci. Návaznost, periodicita a anotace: Časopis Historica Olomucensia, Sborník prací historických je vydáván od roku 2009. Na- vazuje na dlouholetou tradici ediční řady Acta Universitatis Palackianae Olomucensis – Historica, Sborník prací historických, která začala být vydávána v roce 1960. Od dubna 2015 je zařazen do prestižní evropské databáze odborných časopisů ERIH PLUS (Europe- an Reference Index for the Humanities and the Social Sciences). Od roku 2009 je na se- znamu recenzovaných neimpaktovaných periodik vydávaných v České republice. Od roku 2009 vychází dvakrát ročně, s uzávěrkou na konci dubna a na konci října. Oddíl Články a studie obsahuje odborné recenzované příspěvky věnované různým problémům českých a světových dějin. Oddíl Zprávy zahrnuje především informace o činnosti Katedry historie FF UP v Olomouci a jejích pracovišť či dalších historických pracovišť v Olomouci a případ- ně také životopisy a bibliografi e členů katedry. Posledním oddílem časopisu jsou recenze. Výkonný redaktor a adresa redakce: PhDr. Ivana Koucká, Katedra historie FF UP, tř. Svobody 8, 779 00 Olomouc. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Redakční rada: prof. PhDr. Jana Burešová, CSc. – předseda (Katedra historie FF UP v Olomouci), Mgr. Veronika Čapská, Ph.D. (Katedra obecné antropologie FHS UK v Praze), doc. Mgr. Martin Čapský, Ph.D. (Ústav historických věd Filozofi cko-přírodovědecké fakulty SU v Opavě), prof. -

THE YOSEMITE by John Muir CHAPTER I The

THE YOSEMITE By John Muir CHAPTER I The Approach to the Valley When I set out on the long excursion that finally led to California I wandered afoot and alone, from Indiana to the Gulf of Mexico, with a plant-press on my back, holding a generally southward course, like the birds when they are going from summer to winter. From the west coast of Florida I crossed the gulf to Cuba, enjoyed the rich tropical flora there for a few months, intending to go thence to the north end of South America, make my way through the woods to the headwaters of the Amazon, and float down that grand river to the ocean. But I was unable to find a ship bound for South America--fortunately perhaps, for I had incredibly little money for so long a trip and had not yet fully recovered from a fever caught in the Florida swamps. Therefore I decided to visit California for a year or two to see its wonderful flora and the famous Yosemite Valley. All the world was before me and every day was a holiday, so it did not seem important to which one of the world's wildernesses I first should wander. Arriving by the Panama steamer, I stopped one day in San Francisco and then inquired for the nearest way out of town. "But where do you want to go?" asked the man to whom I had applied for this important information. "To any place that is wild," I said. This reply startled him. He seemed to fear I might be crazy and therefore the sooner I was out of town the better, so he directed me to the Oakland ferry. -

No Ring Fracture in Mono Basin, California

No ring fracture in Mono Basin, California Wes Hildreth, Judy Fierstein†, and Juliet Ryan-Davis§ Volcano Science Center, U.S. Geological Survey, Menlo Park, California 94025, USA ABSTRACT influenced its vent pattern. The apparently rhyolite volcanoes. Kistler mapped a shear zone arcuate chain actually consists of three lin- in Mesozoic granitoids that he interpreted as a In Mono Basin, California, USA, a near- ear segments that reflect Quaternary tec- segment of a much broader ring fracture that he circular ring fracture 12 km in diameter was tonic influence and not Cretaceous inheri- postulated to circle beneath the youthful chain proposed by R.W. Kistler in 1966 to have tance. A rhyolitic magma reservoir under of Mono Craters’ rhyolite domes (Fig. 2). The originated as the protoclastic margin of the the central segment of the Mono chain has following critique of Kistler’s ring fracture hy- Cretaceous Aeolian Buttes pluton, to have erupted many times in the late Holocene and pothesis does not diminish our admiration for been reactivated in the middle Pleistocene, as recently as 700 years ago. The ring frac- his pioneering geologic investigation of one of and to have influenced the arcuate trend of ture idea, however, prompted several geo- the more complex and precipitous terrains of the the chain of 30 young (62–0.7 ka) rhyolite physical investigations that sought a much western USA. domes called the Mono Craters. In view of broader magma body, but none identified a Our reinvestigation assembles geologic and the frequency and recency of explosive erup- low-density or low-velocity anomaly beneath geophysical evidence that bears upon the ring tions along the Mono chain, and because the purported 12-km-wide ring, which we fracture hypothesis and Quaternary magmatism.