A BACH NOTEBOOK for TRUMPET

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Current Review

Current Review Johann Bernhard Bach: Orchestral Suites aud 97.770 EAN: 4022143977700 4022143977700 www.musicweb-international.com (2020.07.14) source: http://www.musicweb-international.com/cl... Few musical dynasties of the baroque period were so many-branched as the Bachs. For about two centuries they took leading positions in Saxonia and Thuringia, mostly as organists or as Kapelmeister. Johann Sebastian and his sons are among the most famous members of that dynasty, and some representatives of the previous generation are also rather well-known, such as Johann Christoph and Johann Michael. The present disc includes four overtures or orchestral suites by Johann Bernhard Bach. He is one of the lesser-known members of the Bach family, and of the same generation as Johann Sebastian, his second cousin. Johann Bernhard was born in Erfurt as the son of Johann Aegidius, who from 1682 onwards was director of the town music there, and also occupied the post of organist in two churches. One of his pupils was Johann Gottfried Walther. Johann Bernhard was also taught by his father, and may have been a pupil of Johann Pachelbel as well. His organ works show the latter's influence. Those are an imporant part of his rather small extant oeuvre. The four overtures recorded by the Thüringer Bach Collegium are his only instrumental compositions. They may date from the 1720s, and were written for the court orchestra of Duke Wilhelm of Sachsen-Eisenach. In this ensemble Johann Bernhard acted as keyboard player from 1703 until his death. Three of the overtures have been preserved thanks to Johann Sebastian, who copied the parts for performances of the Collegium Musicum in Leipzig. -

Stadtkirche St. Michael Kirche Gehren

Stadtkirche St. Michael Kirche Gehren Auch Gehren kann in seiner Geschichte auf mehrere Kirchbauten verweisen. Dort, wo heute die Stadtkirche St. Michael steht, befand sich ein Vorgängerbau, dessen erste Erwähnung aus dem Jahre 1521 stammt. Hier war Johann Michael Bach, der Schwiegervater von Johann Sebastian Bach, von 1673 bis 1694 als Organist tätig. Anfang des 18. Jh. wurde diese Kirche zu klein für die ständig wachsende Zahl der Gottesdienstbesucher, da mit dem Ausbau der fürstlichen Verwaltungsstrukturen als „Amt“ Gehren der Ort überregionale 1834 Bedeutung erlangte. Eine 1729 eingeweihte größere Kirche auf dem benachbarten Kirchberg stand allerdings nur 20 Jahre, dann fiel sie einem Brand zum Opfer. So wurde die Kirche am Markt bis 1830 genutzt. Dann riss man sie ab und erbaute an gleicher Stelle im klassizistischen Stil eine Neue. In der „kirchenlosen Zeit“ fanden die Gottesdienste in der Kapelle des Gehrener Schlosses statt. Der Kirchturm der neuen Kirche hatte zunächst eine ebene Plattform. 35 Jahre später erst erhielt er die heutige Spitze mit vier kleinen Ecktürmchen. 1895 wurde eine vom Hof-Orgelbauer Sauer gebaute Orgel installiert. Aus dem gleichen Jahr stammt auch die Kanzel. 1924 schenkte die Fürstin Marie von Schwarzburg- Sondershausen der Kirchgemeinde einige Kunstgegenstände aus der nicht mehr genutzten Schlosskapelle. Diese wurden dadurch kein Opfer der Flammen, die das Schloss 1933 zerstörten. Der etwas streng wirkende Altarraum erhielt in den 1960er Jahren seine heutige Form. In diesem Zusammenhang kam der von der Fürstin Marie gespendete Altar nach Jesuborn. 1917 mussten die drei Bronzeglocken – eine davon fast 450 Jahre alt – zur Einschmelzung abgeführt werden. Heute läuten nun an ihrer Stelle drei Stahlglocken. -

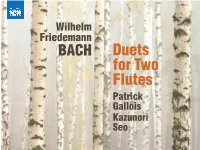

For Two Flutes

Wilhelm Friedemann BACH Duets for Two Flutes Patrick Gallois Kazunori Seo Wilhelm Friedemann Bach (1710–1784) Sonatas has been the object of some speculation.1 It has two-part writing, its rapid outer movements framing a C Six Duets for Two Flutes, F.54–59 been suggested that the Duets in E minor, F.54 and G major, minor Adagio. The Duet in F major, F.57, has at its heart a F.59 may be relatively early works, dating from 1729 or D minor Cantabile, the two parts intricately interwoven, with Born in Weimar in 1710, Wilhelm Friedemann Bach was the Sebastian had abandoned what had been, until his patron’s perhaps from his first years in Dresden. The Duets in E flat a rapid final movement. The demands for virtuosity suggest eldest son of Johann Sebastian Bach by his first wife, Maria marriage, a happy position at court for employment under major, F.55 and F major, F.57 may have been written before the influence of distinguished flautists in Dresden, Pierre- Barbara. When his father moved to Cöthen in 1717 as Court the city council in Leipzig, so his son left the court society of 1741, a date suggested by the use made of extracts for his Gabriel Buffardin, the teacher of Quantz, who was employed Kapellmeister to the young Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen, Dresden for municipal employment in Halle, the birth-place Solfeggi by Quantz, who was then employed by Frederick for many years at the court of the Elector of Saxony and, Wilhelm Friedemann presumably studied at the Lutheran of Handel, who had briefly served as organist there. -

Concerto Italiano | Rinaldo Alessandrini

Concerto Italiano | Rinaldo Alessandrini Programmes | 2022/2023 The complete Madrigal Books of Monteverdi Presenting Monteverdi’s complete Madrigal Books this concert cycle is spread over three seasons starting in 2021/2022. German Orchestral Suites Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Orchestral suite No. 3 in D major BWV 1068 (Original version for strings) Johann Ludwig Bach (1677-1731) Suite in G major for strings and b.c. Johann Bernhard Bach (1676-1749) Ouverture for orchestra No. 3 in E minor Wilhelm Friedemann Bach (1710-1784) Suite (Ouverture) for orchestra in G minor BWV 1070 5 strings and harpsichord “More Bach, please!” | J.S. Bach (1685-1750) Ouverture for strings in d-minor (arr. from French Ouverture BWV 831 by R. Alessandrini) Goldberg Variations BWV 988 (arr. for strings by R. Alessandrini) 5 strings and harpsichord Bach Suites and Concertos | J.S. Bach (1685-1750) Ouverture for strings G major (arr. from BWV 820 and BWV 831 by R. Alessandrini ) Brandenburg concerto no.5 BWV 1050 Orchestral suite no.2 in b minor BWV 1067 5 strings, traverso, harpsichord History of the Italian Madrigal A selection of the finest madrigals by Monteverdi, Marenzio, Luzzaschi, Nenna, Gesualdo, Pecci, Wert, Monte. 6 singers, 2 theorbos Italian Motets for the Virgin Mary Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) Litanie a 6 voci Alessandro Scarlatti (1660-1725) Salve Regina a 4 voci Alessandro Melani (1639-1703) Ave Regina Coelorum a 5 voci Alessandro Scarlatti (1660-1725) Magnificat a 5 voci Giovanni Legrenzi (1626-1690) Litanie a 5 voci Giovanni Legrenzi (1626-1690) alve Regina a 5 voci Giovanni Legrenzi (1626-1690) Ave Regina Coelorum a 5 voci Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643) Magnificat a 6 voci 6 singers, theorbo, organ Konzertdirektion Andrea Hampl • Karl-Schrader-Str. -

ABKÜRZUNGEN 1. Allgemein ADB = Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie

ABKÜRZUNGEN 1. Allgemein ADB = Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie, hrsg. von der Historischen Commission bei der Königlichen Akademie der Wissen- schaften München, 56 Bde., Leipzig 1875 –1912 (Nach- druck 1967 –1971) AfMw = Archiv für Musikwissenschaft, 1918 –1926, 1952 ff. Am. B. = Amalien-Bibliothek (Dauerleihgabe in D-B) AMZ = Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung, Leipzig 1799 –1848 Bach- Kolloquium Rostock = Das Frühwerk Johann Sebastian Bachs. Kolloquium, ver- anstaltet vom Institut für Musikwissenschaft der Universi- tät Rostock 11. –13. September 1990, hrsg. von Karl Heller und Hans-Joachim Schulze, Köln 1995 Bach- Symposium Marburg = Bachforschung und Bachinterpretation heute. Wissen- schaftler und Praktiker im Dialog. Bericht über das Bach- fest-Symposium 1978 der Philipps-Universität Marburg, hrsg. von Reinhold Brinkmann, Kassel 1981 BC = Hans-Joachim Schulze und Christoph Wolff, Bach Com- pendium. Analytisch-bibliographisches Repertorium der Werke Johann Sebastian Bachs, Bd. I / 1– 4, Leipzig 1986 bis 1989 Beißwenger = Kirsten Beißwenger, Johann Sebastian Bachs Notenbib- liothek, Kassel 1992 (Catalogus Musicus. 13.) BG = J. S. Bachs Werke. Gesamtausgabe der Bachgesellschaft, Leipzig 1851–1899 BJ = Bach-Jahrbuch, 1904 ff. BuxWV = Georg Karstädt, Thematisch-systematisches Verzeichnis der musikalischen Werke von Dietrich Buxtehude. Buxte- hude-Werke-Verzeichnis (BuxWV), Wiesbaden 1974 BWV = Wolfgang Schmieder, Thematisch-systematisches Ver- zeichnis der musikalischen Werke von Johann Sebastian Bach. Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis, Leipzig 1950 BWV2 = Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis (wie oben); 2. überarbeitete und erweiterte Ausgabe, Wiesbaden 1990 Bach-JB_2015.indb 5 11.11.15 14:27 6 Abkürzungen BWV2a = Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis. Kleine Ausgabe nach der von Wolfgang Schmieder vorgelegten 2. Ausgabe, hrsg. von Alfred Dürr und Yoshitake Kobayashi, unter Mitarbeit von Kirsten Beißwenger, Wiesbaden 1998 DDT = Denkmäler deutscher Tonkunst, hrsg. -

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach

Wilhelm Friedemann Bach COMPLETE ORGAN MUSIC Filippo Turri Wilhelm Friedemann Bach 1710-1784 The first son of Johann Sebastian and Maria Barbara Bach, Wilhelm Friedemann Complete Organ Music Bach (Weimar, 22 November 1710 – Berlin, 1 July 1784) lived a life that in many respects would fit in perfectly with the biography of a tormented artist of the Drei dreistimmigen Fugen Sieben Choralvorspiele F.38 romantic age. He studied under his father, showing early talent as an instrumentalist Three 3-part Fugues Seven Chorale Preludes F.38 (organist, harpsichordist, violinist) and composer, as well as considerable gifts as 1. Fugue in B flat F.34 2’56 15. I. Nun komm der a mathematician. Given his father’s Pythagorean passions, this latter aptitude is 2. Fugue in F F.33 5’22 Heiden Heiland 1’46 not really as surprising at it might at first seem, yet it is certainly true that Wilhelm 3. Fugue in C minor F.32 6’38 16. II. Christe, der du bist Tag Friedemann was versatile and his interests widespread. At the early age of 23 he was und Licht 2’15 appointed principal organist at the church of St. Sophia in Dresden, and in 1747 Acht dreistimmigen Fugen für Orgel 17. III. Jesu, meine Freude 3’59 became Musikdirektor and organist at the Church of Our Lady in Halle. On account oder Clavier F.31 18. IV. Durch Adams Fall is of his years in Halle, where he married Dorothea Elisabeth Georgi (1721-1791), he is Eight 3-part fugues for Organ ganz verderbt 3’35 often referred to as the “Halle” Bach. -

Benjamin Alard

THE COMPLETE WORK FOR KEYBOARD TOWARDS THE NORTH VERS LE NORD Benjamin Alard Organ & Claviorganum FRANZ LISZT JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685-1750) The C omplete W orks for Keyboard Intégrale de l’Œuvre pour Clavier / Das Klavierwerk Towards the North Vers le Nord | Nach Norden Lübeck Hambourg DIETRICH BUXTEHUDE (1637?-1707) JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH 1 | Choralfantasie “Nun freut euch, lieben Christen g’mein” BuxWV 210 14’31 1 | Toccata BWV 912a, D major / Ré majeur / D-Dur 12’20 Weimarer Orgeltabulatur 2 | Choral “Jesu, meines Lebens Leben” BWV 1107 1’44 JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH JOHANN PACHELBEL 2 | Choral “Herr Christ, der einig Gottes Sohn” BWV Anh. 55 2’22 3 | Choral “Kyrie Gott Vater in Ewigkeit” 2’44 3 | Choral “Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern” BWV 739 4’50 Weimarer Orgeltabulatur JOHANN PACHELBEL (1653-1706) JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH 4 | Fuge, B minor / si mineur / h-Moll 2’46 4 | Choral “Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier” BWV 754 3’22 Weimarer Orgeltabulatur 5 | Fantasia super “Valet will ich dir geben” BWV 735a 3’42 6 | Fuge BWV 578, G minor / sol mineur / g-Moll 3’35 JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH 7 | Fuge “Thema Legrenzianum” BWV 574b, C minor / ut mineur / c-Moll 6’17 5 | Choral “Ach Herr, mich armen Sünder” BWV 742 2’11 8 | Fuge BWV 575, C minor / ut mineur / c-Moll 4’16 6 | Fuge über ein Thema von A. Corelli BWV 579, B minor / si mineur / h-Moll 5’24 7 | Choral “Christ lag in Todesbanden” BWV 718 4’57 JOHANN ADAM REINKEN (1643?-1722) 8 | Fuge BWV 577, G major / Sol majeur / G-Dur 3’43 9 | Choralfantasie “An Wasserflüssen Babylon” 18’42 9 | Partite -

Im Auftrag Der Internationalen Heinrich-Schütz-Gesellschaft E.V. Herausgegeben Von Walter Werbeck in Verbindung Mit Werner Brei

Im Auftrag der Internationalen Heinrich-Schütz-Gesellschaft e.V. herausgegeben von Walter Werbeck in Verbindung mit Werner Breig, Friedhelm Krummacher, Eva Linfield 33. Jahrgang 2011 Bärenreiter Kassel . Basel . London . New York . Praha 2012_schuetz-JB_druck_120531.ind1 1 31.05.2012 10:03:13 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Internationalen Heinrich-Schütz-Gesellschaft e.V. und der Landgraf-Moritz-Stiftung Kassel © 2012 Bärenreiter-Verlag Karl Vötterle GmbH & Co. KG, Kassel Alle Rechte vorbehalten / Printed in Germany Layout: ConText, Carola Trabert – [email protected] ISBN 978-3-7618-1689-9 ISSN 0174-2345 2012_schuetz-JB_druck_120531.ind2 2 31.05.2012 10:03:13 Inhalt Vorträge des Schütz-Festes Kassel 2010 Heinrich Schütz und Europa 7 Silke Leopold Heinrich Schütz in Kassel 19 Werner Breig Europa in der ersten Hälfte des 17. Jahrhunderts 31 Georg Schmidt Music and Lutherian Devotion in the Schütz Era 41 Mary E. Frandsen »Mein Schall aufs Ewig weist«: Das Jenseits und die Kirchenmusik in der lutherischen Orthodoxie 75 Konrad Küster Medien sozialer Distinktion: Funeral- und Gedenkkompositionen des 17. Jahrhunderts im europäischen Vergleich 91 Peter Schmitz Echos in und um »Daphne« 105 Bettina Varwig Heinrich Schütz und Otto Gibel 119 Andreas Waczkat, Elisa Erbe, Timo Evers, Rhea Richter, Arne zur Nieden Heinrich Schütz as European cultural agent at the Danish courts 129 Bjarke Moe Freie Beiträge Eine unbekannte Trauermusik von Heinrich Schütz 143 Eberhard Möller Heinrich Schütz und seine Brüder: Neue Stammbucheinträge 151 Joshua Rifkin Die Verfasser der Beiträge 168 2012_schuetz-JB_druck_120531.ind3 3 31.05.2012 10:03:13 Abkürzungen ADB Allgemeine deutsche Biographie, München u. Leipzig 1876 – 1912 AfMw Archiv für Musikwissenschaft AmZ Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung Bd., Bde. -

Generalbaßlehre of 1738” by Thomas Braatz © 2012

The Problematical Origins of the “Generalbaßlehre of 1738” by Thomas Braatz © 2012 Near the end of 2011 a new volume of the NBA was released by Bärenreiter. It is called a supplement and includes notes and studies on thorough-bass, composition and counterpoint along with a section of Bach’s sketches and drafts and finally in the appendix the more recently discovered aria, BWV 1127. In addition to the well- researched and documented rules on thorough-bass found in the Anna Magdalena Bach’s notebooks, there is a presentation and critical discussion of the recently discovered (1999) counterpoint studies in the form of an exchange between Wilhelm Friedemann Bach and his father, all in autograph documents from the period 1736 to1739 when W. F. Bach was an organist in Dresden. Of great interest is the analysis and discussion of the Precepts and Principles for Playing the Thorough-Bass along with the complete text and musical examples. Below I will present the original German (Appendix 1) along with my English translation (Appendix 2) of the pertinent sections from the NBA editor’s introduction and the critical report covering this document. From this the reader will be able ascertain the spurious1 nature of its origin and claims of authenticity. The Precepts and Principles for Playing Four-Part Thorough-Bass or Accompaniment, or more commonly referred to in its short form as the “Generalbaßlehre of 1738”, has attained a false aura of authenticity since the appearance of Philipp Spitta’s monumental Bach biography in which Spitta printed the entire text of this document that he also analyzed and discussed in greater detail in a music journal in 1882.2 Spitta was the first Bach scholar to recognize the connection between this document and certain paragraphs contained in a treatise by Friedrich Erhard Niedt. -

Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach This article is about the Baroque composer. For his ently at his own initiative, Bach attended St. Michael’s grandson of the same name, see Johann Sebastian Bach School in Lüneburg for two years. After graduating he (painter). For other uses of Bach, see Bach (disambigua- held several musical posts across Germany: he served as tion). Kapellmeister (director of music) to Leopold, Prince of Anhalt-Köthen, Cantor of the Thomasschule in Leipzig, and Royal Court Composer to Augustus III.[4][5] Bach’s health and vision declined in 1749, and he died on 28 July 1750. Modern historians believe that his death was caused by a combination of stroke and pneumonia.[6][7][8] Bach’s abilities as an organist were respected throughout Europe during his lifetime, although he was not widely recognised as a great composer until a revival of inter- est and performances of his music in the first half of the 19th century. He is now generally regarded as one of the greatest composers of all time.[9] 1 Life 1.1 Childhood (1685–1703) See also: Bach family Johann Sebastian Bach was born in Eisenach, Saxe- Eisenach, on 21 March 1685 O.S. (31 March 1685 N.S.). He was the son of Johann Ambrosius Bach, the direc- tor of the town musicians, and Maria Elisabeth Läm- merhirt.[10] He was the eighth child of Johann Ambro- Portrait of Bach, aged 61, Haussmann, 1748 sius, (the eldest son in the family was 14 at the time of Bach’s birth)[11] who probably taught him violin and the basics of music theory.[12] His uncles were all professional Johann Sebastian Bach[1] (31 March [O.S. -

Baroque and Classical Style in Selected Organ Works of The

BAROQUE AND CLASSICAL STYLE IN SELECTED ORGAN WORKS OF THE BACHSCHULE by DEAN B. McINTYRE, B.A., M.M. A DISSERTATION IN FINE ARTS Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Chairperson of the Committee Accepted Dearri of the Graduate jSchool December, 1998 © Copyright 1998 Dean B. Mclntyre ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am grateful for the general guidance and specific suggestions offered by members of my dissertation advisory committee: Dr. Paul Cutter and Dr. Thomas Hughes (Music), Dr. John Stinespring (Art), and Dr. Daniel Nathan (Philosophy). Each offered assistance and insight from his own specific area as well as the general field of Fine Arts. I offer special thanks and appreciation to my committee chairperson Dr. Wayne Hobbs (Music), whose oversight and direction were invaluable. I must also acknowledge those individuals and publishers who have granted permission to include copyrighted musical materials in whole or in part: Concordia Publishing House, Lorenz Corporation, C. F. Peters Corporation, Oliver Ditson/Theodore Presser Company, Oxford University Press, Breitkopf & Hartel, and Dr. David Mulbury of the University of Cincinnati. A final offering of thanks goes to my wife, Karen, and our daughter, Noelle. Their unfailing patience and understanding were equalled by their continual spirit of encouragement. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ii ABSTRACT ix LIST OF TABLES xi LIST OF FIGURES xii LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES xiii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS xvi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 11. BAROQUE STYLE 12 Greneral Style Characteristics of the Late Baroque 13 Melody 15 Harmony 15 Rhythm 16 Form 17 Texture 18 Dynamics 19 J. -

The Keyboard Music of Wilhelm Friedemann Bach Updates and Corrections

The Keyboard Music of Wilhelm Friedemann Bach Updates and Corrections Chapter 1 “But any biography of these composers must remain incomplete in ways that is not the case for musicians whose inner life, emotional as well as musical, is better documented . .” (p. 5). Friedemann’s inner life has nevertheless been reconstructed fictionally in the novels, films, and operas mentioned on pages 12–13. To these must be added Lauren Belfer’s 2016 novel And After the Fire, which, although continuing the tradition begun by Brachvogel of making Friedemann a lover of certain wealthy young women, in other respects paints plausible pictures of both the aging composer and his youthful pupil Sara Levy. “One long-standing enigma . his fourth cousin” (p. 11) The exact relationship of Friedemann to J. C. Bach of Halle is less certain and probably more remote than is indicated here. The “Halle Clavier Bach” was descended from Lips (Philippus) Bach, who might have been a brother or son of Veit Bach (Friedemann’s great-great-great-grandfather). All that can be said assuredly is that the two probably were distantly related, with one or more common ancestors, but none within five generations as suggested here. J. C. Bach of Halle belonged to the same Meiningen branch of the family that also produced the composer Johann Ludwig (his uncle) and the painters Gottlieb Friedrich and Samuel Anton Bach (his cousins). Chapter 2 “I do not give instruction” (see p. 292n. 27) The claim that Friedemann did not teach during his Berlin years is based not only on Friedemann’s own declaration but on a 1779 letter of Kirnberger to Forkel (in Bitter, 2:323: “auch Lection geben mag er nicht”).