Li. LID. a REPORT of the CIRCUMSTANCES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OCPS Students Bring Home GOLD from National FFA Convention Colonial High School FFA Chapter Earns Gold Emblem Award

OCPS students bring home GOLD from National FFA Convention Colonial High School FFA Chapter earns Gold Emblem Award Nov. 9, 2017 – Orange County Public Schools FFA students from multiple schools bring back national awards from the 90th National FFA Convention held in Indianapolis, IN. With over 67,000 attendees, FFA members from across the country came together attending leadership workshops, motivational presentations, business sessions, career expo and awards ceremony. The Colonial High School FFA Chapter won the Gold Emblem Award and placed second in the nation. This is the highest award that an Orange County FFA Chapter has received in a national FFA career development event. The team members (pictured in the top left photo) are: Ashton Santos, Jenna Ausburger, Sara Humphrey and Cameron Ramola. They are joined by the event coordinator (on left) and Orlando-Colonial HS FFA Teacher/Advisor, Ms. Caela Paioff (on right). Colonial’s FFA Chapter first earned the state championship in the Environmental Science CDE (Career Development Event) last January, earning the opportunity to represent Florida at the national level. The purpose of the FFA Environmental Science Career Development Event is to stimulate student interest and to promote environmental and natural resource instruction in the agricultural education curriculum and to provide recognition for those who have demonstrated skills and competencies as a result of environmental and natural resource instruction. Orange County FFA was well represented and received additional notable awards: -

Community Meeting Colonial High School Capital Projects November 8, 2017

Orange County Public Schools Welcome! Please sign in on your mobile device: http://communitymeeting.ocps.net/ Community Meeting Colonial High School Capital Projects November 8, 2017 Colonial High School 1 Orange County Public Schools Colonial High School Community Meeting Meeting Agenda November 8, 2017 6:00 PM •Welcome – School Board Member: Daryl Flynn •Introductions – Lauren Roth/ Facilities Communications •Project Update – Architect: Contractor: TBD •Questions and Answers •Adjournment Colonial High School 2 Orange County Public Schools 17 Portables 36 Practice Bus 33 02 03 OLEANDER DR. 01 32 Good 06 Sheperd 04 Catholic Church SEMORAN BLVD. SEMORAN 21 Practice 05 Parent 27 Baseball LAKE Softball WADE Retention RANDIA RD. Football Field & Track north Campus Overview Colonial High School 3 Colonial High School Master Plan Phase 1 17 • Demolish Portables Existing Auditorium • Demolish Existing Auditorium Practice Existing 02 Music • Existing Music Remains in Operation 03 01 32 06 04 • Renovate Bldgs. 01, 02, 03, 04, 05, 06, 21 08, 17, 27, and 32 05 Baseball 27 Softball • eReplac 3 Chillers • Replace Track New Track north 0’ 200’ 2018 2019 MAY JUNE JULY AUG. SEPT. OCT. NOV. DEC. JAN. FEB. MAR. APR. MAY JUNE JULY AUG. SEPT. OCT. NOV. SUMMER 4 Colonial High School Master Plan Phase 2 17 New Music • Construct New Auditorium & Music New Building Auditorium Open Field / Practice Field Existing 02 Music • Existing Music Remains in Operation 03 01 New 32 Ag-Lab 06 04 21 • Renovate Building 21 05 Baseball 27 north Softball 0’ 100’ 2018 2019 MAY JUNE JULY AUG. SEPT. OCT. NOV. DEC. JAN. FEB. MAR. APR. -

Directions Are from Espn's Wide World of Sports

DIRECTIONS TO OFF-SITE VENUE Page 1 ESPN’s Wide World of Sports Complex HP Fieldhouse (COURTS 1-6) Jostens Center (COURTS 7-12) 700 South Victory Way Kissimmee, FL 34747 (407) 828-3267 • Traveling Westbound on I-4 Take I-4 to exit 65/old 26 D (Osceola Parkway West) Take a left onto Victory Way • Traveling Eastbound on I-4 Take I-4 to exit 65/old 26 C (Osceola Parkway West) Take a left onto Victory Way DIRECTIONS ARE FROM ESPN’S WIDE WORLD OF SPORTSTM COMPLEX Orlando Sports Complex (COURTS 13 thru 18) 6700 Kingspointe Parkway Orlando, FL 32819 • From Victory Way turn right onto Osceola Parkway (1.0 mile) • Merge onto I-4 E ramp on left toward ORLANDO (8.5 miles) • Take Exit 74A for Sand Lake RD/SR-482 (toward International Drive) • Turn RIGHT onto Sand Lake RD (2.2 miles) • While driving East on Sand Lake Road, if you get to John Young Parkway turn around, you’ve gone too far! • Turn LEFT onto KINGSPOINTE PKWY (0.5 mile) • OSC is on the right DIRECTIONS TO OFF-SITE VENUE Page 2 The Foundation Academy (COURT 19-20) 15304 Tilden Road Winter Garden, FL 34787 • From Victory Way turn left onto Osceola Parkway • Take ramp toward Disney/Magic Kingdom and merge onto World Dr • Take ramp towards Epcot Resorts/Downtown Disney • Take ramp towards Blizzard Beach/Animal Kingdom • Turn left onto E. Buena Vista Dr • Turn slight right on Western Way • Take the SR-429 Toll N ramp and merge onto FL-429 Toll Dan Webster Beltway • Take Seidel Rd exit, Exit 11. -

OCPS Commencement Ceremonies Run May 20-28

ORANGE COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS OCPS commencement ceremonies run May 20-28 May 20, 2019 – Orange County Public Schools started commencement ceremonies for our 20 traditional high schools. They run through May 28. We interviewed one graduating senior at each high school for our #OCPSGrads series of videos on Facebook and Twitter. These students are a sample of the talent, intellect and tenacity of our 14,000 graduates. Each has an amazing story. Those already published are hyperlinked below, listed alphabetically by school. (Those without hyperlinks will be published in the coming days.) Members of the news media are welcome to attend any OCPS graduation, but must make arrangements for entrance directly with the venue hosting the event (Amway Center or UCF Addition Arena). After making arrangements, please let us know which one(s) you will attend. Apopka High School (May 20, Amway Center, 2 p.m.) Hurricane Maria forced Carlos Rivera Colon and his family to leave their home and rebuild their lives in Central Florida. Carlos quickly immersed himself in the school culture by joining the Archery Club, and will be heading to the Marines after graduation. Boone High School (May 21, Addition Arena, 7:30 p.m.) Enrolling in the criminal justice magnet pushed Marlon Allen out of his comfort zone, and provided him a culturally diverse and academically rigorous education. This four-year varsity basketball letterman plans to major in business and journalism. Plays Basketball Colonial High School (May 20, Amway Center, 8:30 a.m.) Instead of coasting through senior year, Yohanna Torres Sanchez continued to reach for the highest level of academic excellence, taking 10 academic courses. -

OCPS District Directory

OCPS District Directory Florida Relay 7-1-1 Florida Telecommunications Relay, Inc., referred to as Florida Relay 7-1-1, is a communications link for people who are deaf, hard of hearing, deaf/blind, or speech impaired. For example, this service can be used when school staff members need to talk to a deaf parent or when the parent calls the school. Here is how it works: Hearing callers trying to reach deaf or hard-of-hearing callers dial 7-1-1 and give the operator the 10-digit telephone number of the person they are trying to reach. The operator will ask them if they have used the relay service before and give a short narrative if not. They will then ask the person to hold while the call is connected. The operator will type everything said by the hearing person and read back the responses from the D/HH caller. Once connected, the hearing person should speak at a slow-moderate rate and say “go ahead” when it is the caller’s turn to talk. This process is similar to two-way radios needing to say “over” as the conversation proceeds back and forth. The OCPS Telephone Directory is produced by the District Information Office. Please notify Wanda Cocco at 407-317-3237 or [email protected] of any changes or corrections. To order additional copies of the OCPS Telephone Directory, contact Printing Services at 407.850.5110, or e-mail your request to: [email protected]. OCPS EEO Non-Discrimination Statement The School Board of Orange County, Florida, does not discriminate in admission or access to, or treatment or employment in its programs and activities, on the basis of race, color, religion, age, sex, national origin, marital status, disability, genetic information, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, or any other reason prohibited by law. -

2018 Hoop Exchange Player Showdown Newsletter

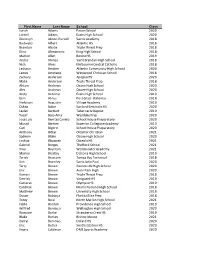

First Name Last Name School Class Isaiah Adams Paxon School 2020 Latrell Aikens Evans High School 2020 Donovyn Akoon-Purcell Saints Academy 2018 Rodwens Albert Atlantic HS 2018 Brandon Alcide Triple Threat Prep 2018 Dino Alimanovic King High School 2018 Marlon Allen Boone HS 2019 Andre Alonzo Saint Brendan High School 2018 Nick Alves Melbourne Central Catholic 2018 Jashaun Amaker Atlantic Community High School 2020 James Ametepe Westwood Christian School 2018 Zachary Anderson Apopka HS 2020 Malik Anderson Triple Threat Prep 2018 Alston Andrews Ocoee High School 2020 Alex Andrews Ocoee High School 2020 Andy Antoine Evans High School 2019 Gim Atilus Post Grad - Bahamas 2018 Herbison Augustin Village Academy 2019 Oshea Baker Sanford Seminole HS 2020 Jaelen Bartlett Tabernacle Baptist 2019 Yussif Basa-Ama Westlake Prep 2020 Jose Luis Benitez Canelo School House Preparatory 2020 Murad Berrien Superior Collegiate Academy 2019 Carl Bigord School House Preparatory 2020 Anthony Bittar Oldsmar Christian 2021 Sadeem Blake Ocoee High School 2020 Joshua Blazquez Osceola HS 2021 Gabriel Borges The Rock School 2021 Troy Boynton Westminster Academy 2021 Marlon Bradley Deltona High School 2019 Tyrick Brascom Tampa Bay Technical 2018 Kirt Bromley Saint John Paul 2020 Terry Brown Gainesville High School 2020 Eric Brown Avon Park High 2020 Kamari Brown Triple Threat Prep 2018 Derrick Brown Vanguard HS 2019 Camaren Brown Olympia HS 2019 Cardinal Brown Miami Norland High School 2018 Matthew Brown University High School 2018 Dusan Bubanja Florida Elite Prep -

Community Meeting Title

August 12, 2020 40% Construction Community Meeting High School Site 80-H-SW-4 Welcome! This meeting will begin shortly. 1 High School Site 80-H-SW-4 Meeting Agenda August 12, 2020, 5:00 PM • Welcome – School Board Member: Linda Kobert • Introductions – Lauren Roth/ Facilities Communications • School Naming: Principal Guy Swenson • Project Update – David Torbert, AIA, NCARB Freddy Torres, PM • Questions and Answers • Adjournment 3 Welcome Message from District 3 Board Member Linda Kobert Site 80-H-SW-4 4 Introductions by Senior manager, Facilities Communications Lauren Roth Site 80-H-SW-4 5 Rezoning Process School Board Policy JC Step 1 - Superintendent commences rezoning Step 2 - Calendar (Timeline) developed Step 3 - Calendar shared Step 4 - Research, data collection and meetings with internal stakeholders Step 5 - Community Meeting(s) September 2020 Step 6 - Rule Development Workshop September 2020 Step 7 - Public Hearing October 2020 Step 8 - Storage of materials6 Site 80-6H-SW-4 6 School Naming Principal Guy Swenson • Introduction • Site 80-H-SW-4 web site: https://tinyurl.com/Site80HS • School naming survey: https://forms.gle/tFbKABCxjoxyXAGx8 • Mascot,Colors 7 Site 80-H-SW-4 Site Location 80-H-SW-4 DR. PHILLIPS HS Parkside Hilton Sand Grand Vacations Lake ORANGE COUNTY CONVENTION CENTER BEACHLINE FREEDOM HS Dr. Phillips Community SEAWORLD SITE 80 Park NEW HIGH SCHOOL Villas of ROAD VINELAND APOPKA S. Grand Cypress Jewish Community WINTER GARDEN VINELAND ROAD GARDEN VINELAND WINTER Center Lake north Willis 441 ROAD STATE New Lake Connector Ruby Road S. JOHN YOUNG PARKWAY (By County) 8 Site Aerial 80-H-SW-4 Dr. -

Accredited Secondary Schools in the United States. Bulletin 1928, No. 26

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF EDUCATION BULLETIN, 1928, No. 26 ACCREDITED SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN THE UNITED STATES PREPARED IN THE DIVISION OF STATISTICS FRANK M. PHILLIPS CHIEF W ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION MAY BE PROCURED FROM THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS U.S.GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON, D. C. AT 20 CENTS PER COPY i L 111 .A6 1928 no.26-29 Bulletin (United States. Bureau of Education) Bulletin CONTENTS Page Letter of transmittal_ v Accredited secondary school defined_ 2 Unit defined_ 2 Variations in requirements of accrediting agencies_ 3 Methods of accrediting___ 4 Divisions of the bulletin_x 7 Part I.—State lists_ 8 Part II.—Lists of schools accredited by various associations-__ 110 Commission of the Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools of the Southern States_ 110 Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools of the Middle States and Maryland___ 117 New England College Entrance Certificate Board_ 121 North Central Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools_ 127 Northwest Association of Secondary and Higher Schools_ 141 in • -Hi ■: ' .= LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL Department of the Interior, Bureau of Education, Washington, D. C., October 26, 1928. Sir: Secondary education continues to grow and expand. The number of high-school graduates increases from year to year, and the percentage of these graduates who go to higher institutions is still on the increase. It is imperative that a list of those secondary schools that do a standard quantity and quality of work be accessible to students who wish to do secondary school work and to those insti¬ tutions to whom secondary school graduates apply for admission. -

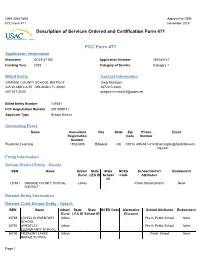

Description of Services Ordered and Certification Form 471 FCC Form

OMB 3060-0806 Approval by OMB FCC Form 471 November 2015 Description of Services Ordered and Certification Form 471 FCC Form 471 Application Information Nickname OC18-47103 Application Number 181042141 Funding Year 2018 Category of Service Category 1 Billed Entity Contact Information ORANGE COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT Greg McIntosh 445 W AMELIA ST ORLANDO FL 32801 407-317-3200 407-317-3200 [email protected] Billed Entity Number 127681 FCC Registration Number 0011598141 Applicant Type School District Consulting Firms Name Consultant City State Zip Phone Email Registration Code Number Number Funds for Learning 16024808 Edmond OK 73013 405-341-4140 jharrington@fundsforlearn ing.com Entity Information School District Entity - Details BEN Name Urban/ State State NCES School District Endowment Rural LEA ID School Code Attributes ID 127681 ORANGE COUNTY SCHOOL Urban Public School District None DISTRICT Related Entity Information Related Child School Entity - Details BEN Name Urban/ State State NCES Code Alternative School Attributes Endowment Rural LEA ID School ID Discount 35788 LOVELL ELEMENTARY Urban Pre-K; Public School None SCHOOL 35794 WHEATLEY Urban Pre-K; Public School None ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 35795 PIEDMONT LAKES Urban Public School None MIDDLE SCHOOL Page 1 BEN Name Urban/ State State NCES Code Alternative School Attributes Endowment Rural LEA ID School ID Discount 35796 PRAIRIE LAKE Urban None Pre-K; Public School None ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 35809 APOPKA ELEMENTARY Urban None Pre-K; Public School None SCHOOL 35811 DREAM LAKE Urban None -

High School Theatre Teachers

High School Theatre Teachers FIRST NAME LAST NAME SCHOOL ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP Pamela Vallon-Jackson AGAWAM HIGH SCHOOL 760 Cooper St Agawam MA 01001 John Bechtold AMHERST PELHAM REGIONAL HIGH SCHOOL 21 Matoon St Amherst MA 01002 Susan Comstock BELCHERTOWN HIGH SCHOOL 142 Springfield Rd Belchertown MA 01007 Denise Freisberg CHICOPEE COMPREHENSIVE HIGH SCHOOL 617 Montgomery St Chicopee MA 01020 Rebecca Fennessey CHICOPEE COMPREHENSIVE HIGH SCHOOL 617 Montgomery St Chicopee MA 01020 Deborah Sali CHICOPEE HIGH SCHOOL 820 Front St Chicopee MA 01020 Amy Davis EASTHAMPTON HIGH SCHOOL 70 Williston Ave Easthampton MA 01027 Margaret Huba EAST LONGMEADOW HIGH SCHOOL 180 Maple St East Longmeadow MA 01028 Keith Boylan GATEWAY REGIONAL HIGH SCHOOL 12 Littleville Rd Huntington MA 01050 Eric Johnson LUDLOW HIGH SCHOOL 500 Chapin St Ludlow MA 01056 Stephen Eldredge NORTHAMPTON HIGH SCHOOL 380 Elm St Northampton MA 01060 Ann Blake PATHFINDER REGIONAL VO-TECH SCHOOL 240 Sykes St Palmer MA 01069 Blaisdell SOUTH HADLEY HIGH SCHOOL 153 Newton St South Hadley MA 01075 Sean Gillane WEST SPRINGFIELD HIGH SCHOOL 425 Piper Rd West Springfield MA 01089 Rachel Buhner WEST SPRINGFIELD HIGH SCHOOL 425 Piper Rd West Springfield MA 01089 Jessica Passetto TACONIC HIGH SCHOOL 96 Valentine Rd Pittsfield MA 01201 Jolyn Unruh MONUMENT MOUNTAIN REGIONAL HIGH SCHOOL 600 Stockbridge Rd Great Barrington MA 01230 Kathy Caton DRURY HIGH SCHOOL 1130 S Church St North Adams MA 01247 Jesse Howard BERKSHIRE SCHOOL 245 N Undermountain Rd Sheffield MA 01257 Robinson ATHOL HIGH SCHOOL -

High School Site 80-H-SW-4

September 12, 2019 100% Design /Construction kick off Community Meeting High School Site 80-H-SW-4 Please sign in on your mobile device: http://communitymeeting.ocps.net/ 1 High School Site 80-H-SW-4 Meeting Agenda September 12, 2019, 6:00 PM • Welcome – School Board Member: Pam Gould • Introductions – Lauren Roth/ Facilities Communications • Project Update – David Torbert, AIA, NCARB Richard Rodriguez- • Questions and Answers • Adjournment 1 Site Location 80-H-SW-4 DR. PHILLIPS HS Parkside Hilton Sand Grand Vacations Lake ORANGE COUNTY CONVENTION CENTER BEACHLINE FREEDOM HS Dr. Phillips Community SEAWORLD SITE 80 Park NEW HIGH SCHOOL Villas of S.ROAD VINELAND APOPKA Grand Cypress Jewish Community WINTER GARDEN VINELAND ROAD GARDEN VINELAND WINTER Center Lake north Willis 441 ROAD STATE New Lake Connector Ruby Road S. JOHN YOUNGPARKWAY (By County) 2 Site Aerial 80-H-SW-4 Dr. Phillips Sand Lake Community Park FENTON ROAD Jewish Community Center High School Site 80-H-W-4 (+/-50 Acres) S.ROAD VINELAND APOPKA New Connector Road (By County) Park Soleil Lake Willis north Lake Ruby 3 Site Plan 80-H-SW-4 Baseball Retention Softball Practice Practice Field Field Stadium Track Tennis Basketball & Field Shadehouse & Greenhouse Service Field Future Expansion House Fencing Bike Racks Cafeteria 3-Story Academics Bus Loop & Staff Parking Courtyard Student Bus DropBus Parking Admin. Auditorium Music Media Gym FRONT DOOR Parent Drop Visitor Retention Parking Full Median Student Stations = 2,776 Daryl Carter Parkway north Opening 0’ 200’ Parking = 777 -

Frequently Asked Questions Digital Learning Devices for Digital Learning

Digital Learning Program Laptop Stand Tent Tablet Digital Learning has LaunchED at Orange County Public Schools Frequently Asked Questions Digital Learning Devices for Digital Learning What is digital learning? Where will my student their device. Teachers will How will my child get Digital learning is a combination access their textbooks? work with students on technical support if they of technology, digital content and Student textbooks are available in responsible use and safekeeping encounter issues? instruction used to strengthen both online and offline formats. of their device. Additionally, Students will receive technical a student’s learning experience. Online textbooks are accessible each device is equipped with support from the school Library It helps out students meet the through launch.ocps.net. the CompuTrace system, so Media Specialist and Technology Florida State Standards in order stolen devices can be disabled Service Representative during to prepare them for the 21st Where will my student and recovered. If loss or theft school hours. century workplace. produce and store work? is suspected, parents should Students will produce and store immediately notify OCPS by How long does the device What is the difference all work in a cloud-based platform calling 407.317.3290. Additionally, battery last? What if a between one-to-one such as Google Apps for Education, students should immediately student’s device battery runs and BYOD? which offers applications for report a lost or stolen device to out during the day? One-to-one is an initiative to word processing, presentations, their teacher. Damaged devices Students are advised to plug in equip every student with a device spreadsheets, and more.