Travancore Tortoise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Struggle of the Linguistic Minorities and the Formation of Pattom Colony

ADVANCE RESEARCH JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCE A CASE STUDY Volume 9 | Issue 1 | June, 2018 | 130-135 e ISSN–2231–6418 DOI: 10.15740/HAS/ARJSS/9.1/130-135 Visit us : www.researchjournal.co.in Struggle of the linguistic minorities and the formation of Pattom Colony C.L. Vimal Kumar Department of History, K.N.M. Government Arts and Science College, Kanjiramkulam, Thiruvananthapuram (Kerala) India ARTICLE INFO : ABSTRACT Received : 07.03.2018 Land has many uses but its availability is limited. During the early 1940s extensive Accepted : 28.05.2018 food shortages occurred throughout Travancore. As a result, the government opened forestlands on an emergency basis for food cultivation and in 1941 granted exclusive cultivation rights known as ‘Kuthakapattam’ was given (cultivation on a short-term KEY WORDS : lease) in state forest areas. Soon after independence, India decided to re-organize Kuthakapattam, Annas, Prathidwani, state boundaries on a linguistic basis. The post Independence State reorganization Pattayam, Blocks, Pilot colony period witnessed Tamil-Malayali dispute for control of the High Ranges. The Government of Travancore-Cochin initiated settlement programmes in the High Range HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE : areas in order to alter the regional linguistic balance. Pattom colony, which was Vimal Kumar, C.L. (2018). Struggle of sponsored by Pattom Thanupillai ministry, as a part of High Range colonization scheme. the linguistic minorities and the formation It led to forest encroachment, deforestation, soil erosion, migration, conflict over control of Pattom Colony. Adv. Res. J. Soc. Sci., of land and labour struggle and identity crisis etc. 9 (1) : 130-135, DOI: 10.15740/HAS/ ARJSS/9.1/130-135. -

Travancore Engineering College, Oyoor, Kollam (Unaided College) - Shifting of 6 Th and 8 Th Semester Students- 2016-17- Sanctioned- Orders Issued

UNIVERSITY OF KERALA (Abstract) Travancore Engineering College, Oyoor, Kollam (Unaided College) - shifting of 6 th and 8 th semester students- 2016-17- sanctioned- orders issued. ACADEMIC ‘BI’ SECTION No. AcBI/12235/2017 Thiruvananthapuram, Dated: 17.03.2017 Read: 1.UO No.Ac.BI/13387/2002-03 dated 23.05.2003 2.Letter No. ASC(P)19/17/HO/TVPM/ENGG/TEC dated 15.02.2017 from the Admission Supervisory Committee for Professional Colleges. 3.Additional item No.2 of the minutes of the meeting of the Syndicate held on 10.02.2017. 4.Minutes of the meeting of the Standing Committee of the Syndicate on Affiliation of Colleges held on 27.02.2017 ORDER The University of Kerala vide paper read (1) above granted provisional affiliation to the Travancore Engineering College, Oyoor, Kollam to function on self financing basis from the academic year 2002-03. Various complaints had been received from the students of Travancore Engineering College, Oyoor, Kollam, their parents and teachers regarding the non conduct of classes and non payment of salary to teachers. In view of the above grave issues in the college, the Admission Supervisory Committee vide paper read as (2) above requested the University to take necessary steps to transfer the students of S6 and S8 to some other college/ colleges of Engineering. The Syndicate held on 10.02.2017 considered the representation submitted by the Students of Travancore Engineering College, Oyoor and resolved to entrust the Convenor, Standing Committee of the Syndicate on Examinations and Students Discipline and the Controller of Examinations to reallocate the students to neighboring college for the conduct of lab examinations for the 5 th Semester students and to work out the modalities for their registration to the 6 th Semester. -

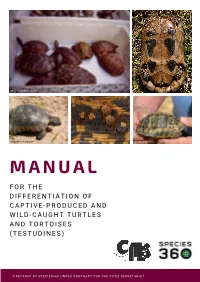

Manual for the Differentiation of Captive-Produced and Wild-Caught Turtles and Tortoises (Testudines)

Image: Peter Paul van Dijk Image:Henrik Bringsøe Image: Henrik Bringsøe Image: Andrei Daniel Mihalca Image: Beate Pfau MANUAL F O R T H E DIFFERENTIATION OF CAPTIVE-PRODUCED AND WILD-CAUGHT TURTLES AND TORTOISES (TESTUDINES) PREPARED BY SPECIES360 UNDER CONTRACT FOR THE CITES SECRETARIAT Manual for the differentiation of captive-produced and wild-caught turtles and tortoises (Testudines) This document was prepared by Species360 under contract for the CITES Secretariat. Principal Investigators: Prof. Dalia A. Conde, Ph.D. and Johanna Staerk, Ph.D., Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, https://www.species360.orG Authors: Johanna Staerk1,2, A. Rita da Silva1,2, Lionel Jouvet 1,2, Peter Paul van Dijk3,4,5, Beate Pfau5, Ioanna Alexiadou1,2 and Dalia A. Conde 1,2 Affiliations: 1 Species360 Conservation Science Alliance, www.species360.orG,2 Center on Population Dynamics (CPop), Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark, 3 The Turtle Conservancy, www.turtleconservancy.orG , 4 Global Wildlife Conservation, globalwildlife.orG , 5 IUCN SSC Tortoise & Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group, www.iucn-tftsG.org. 6 Deutsche Gesellschaft für HerpetoloGie und Terrarienkunde (DGHT) Images (title page): First row, left: Mixed species shipment (imaGe taken by Peter Paul van Dijk) First row, riGht: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with damaGe of the plastron (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, left: Wild Testudo marginata from Greece with minor damaGe of the carapace (imaGe taken by Henrik BrinGsøe) Second row, middle: Ticks on tortoise shell (Amblyomma sp. in Geochelone pardalis) (imaGe taken by Andrei Daniel Mihalca) Second row, riGht: Testudo graeca with doG bite marks (imaGe taken by Beate Pfau) Acknowledgements: The development of this manual would not have been possible without the help, support and guidance of many people. -

Supremacy of Dutch in Travancore (1700-1753)

http://www.epitomejournals.com Vol. 4, Issue 6, June 2018, ISSN: 2395-6968 SUPREMACY OF DUTCH IN TRAVANCORE (1700-1753) Dr. B. SHEEBA KUMARI, Assistant Professor, Department of History, S. T. Hindu College, Nagercoil - 629 002. ABSTRACT in Travancore especially the Dutch from 1700 to 1753 A.D. was noted worthy in Travancore, a premier princely state of the history of the state. In this context, this south India politically, occupied an paper high lights the part of the Dutch to important place in Travancore history. On attain the political supremacy in the eve of the eighteenth century the Travancore. erstwhile state Travancore was almost like KEYWORDS a political Kaleidoscope which was greatly Travancore, Kulachal, Dutch Army, disturbed by internal and external Ettuveettil Pillamar, Marthanda Varma, dissensions. The internal feuds coupled Elayadathu Swarupam with machinations of the European powers. Struggled for political supremacy RESEARCH PAPER Travancore the princely state became an attractive for the colonists of the west from seventeenth century onwards. The Portuguese, the Dutch and the English developed commercial relations with the state of Travancore1. Among the Europeans the Portuguese 70 BSK Impact Factor = 3.656 Dr. Pramod Ambadasrao Pawar, Editor-in-Chief ©EIJMR All rights reserved. http://www.epitomejournals.com Vol. 4, Issue 6, June 2018, ISSN: 2395-6968 were the first to develop commercial contacts with the princes, and establish and fortress in the regions2. Their possessions were taken over by the later adventurers, the Dutch3. The aim of the Dutch in the beginning of the seventeenth century was to take over the whole of the Portuguese trading empire in Asia. -

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises

The Conservation Biology of Tortoises Edited by Ian R. Swingland and Michael W. Klemens IUCN/SSC Tortoise and Freshwater Turtle Specialist Group and The Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) No. 5 IUCN—The World Conservation Union IUCN Species Survival Commission Role of the SSC 3. To cooperate with the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is IUCN's primary source of the in developing and evaluating a data base on the status of and trade in wild scientific and technical information required for the maintenance of biological flora and fauna, and to provide policy guidance to WCMC. diversity through the conservation of endangered and vulnerable species of 4. To provide advice, information, and expertise to the Secretariat of the fauna and flora, whilst recommending and promoting measures for their con- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna servation, and for the management of other species of conservation concern. and Flora (CITES) and other international agreements affecting conser- Its objective is to mobilize action to prevent the extinction of species, sub- vation of species or biological diversity. species, and discrete populations of fauna and flora, thereby not only maintain- 5. To carry out specific tasks on behalf of the Union, including: ing biological diversity but improving the status of endangered and vulnerable species. • coordination of a programme of activities for the conservation of biological diversity within the framework of the IUCN Conserva- tion Programme. Objectives of the SSC • promotion of the maintenance of biological diversity by monitor- 1. -

Factors Influencing the Occurrence and Vulnerability of the Travancore Tortoise Indotestudo Travancorica in Protected Areas in South India

Factors influencing the occurrence and vulnerability of the Travancore tortoise Indotestudo travancorica in protected areas in south India V. DEEPAK and K ARTHIKEYAN V ASUDEVAN Abstract Protected areas in developing tropical countries under pressure from high human population density are under pressure from local demand for resources, and (Cincotta et al., 2000), with enclaves inhabited by margin- therefore it is essential to monitor rare species and prevent alized communities that traditionally depend on forest overexploitation of resources. The Travancore tortoise resources for their livelihoods (Anand et al., 2010). Indotestudo travancorica is endemic to the Western Ghats The Travancore tortoise Indotestudo travancorica is in southern India, where it inhabits deciduous and evergreen endemic to the Western Ghats. It inhabits evergreen, semi- forests. We used multiple-season models to estimate site evergreen, moist deciduous and bamboo forests and rubber occupancy and detection probability for the tortoise in two and teak plantations (Deepaketal., 2011).The species occursin protected areas, and investigated factors influencing this. riparian patches and marshes and has a home range of 5.2–34 During 2006–2009 we surveyed 25 trails in four forest ha (Deepak et al., 2011). Its diet consists of grasses, herbs, fruits, types and estimated that the tortoise occupied 41–97%of crabs, insects and molluscs, with occasional scavenging on the habitat. Tortoise presence on the trails was confirmed by dead animals (Deepak & Vasudevan, 2012). It is categorized as sightings of 39 tortoises and 61 instances of indirect evidence Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List and listed in Appendix II of of tortoises. There was considerable interannual variation CITES (Asian Turtle Trade Working Group, 2000). -

The Ascent of 'Kerala Model' of Public Health

THE ASCENT OF ‘KERALA MODEL’ OF PUBLIC HEALTH CC. Kartha Kerala Institute of Medical Sciences, Trivandrum, Kerala [email protected] Kerala, a state on the southwestern Coast of India is the best performer in the health sector in the country according to the health index of NITI Aayog, a policy think-tank of the Government of India. Their index, based on 23 indicators such as health outcomes, governance and information, and key inputs and processes, with each domain assigned a weight based on its importance. Clearly, this outcome is the result of investments and strategies of successive governments, in public health care over more than two centuries. The state of Kerala was formed on 1 November 1956, by merging Malayalam-speaking regions of the former states of Travancore-Cochin and Madras. The remarkable progress made by Kerala, particularly in the field of education, health and social transformation is not a phenomenon exclusively post 1956. Even during the pre-independence period, the Travancore, Cochin and Malabar provinces, which merged to give birth to Kerala, have contributed substantially to the overall development of the state. However, these positive changes were mostly confined to the erstwhile princely states of Travancore and Cochin, which covered most of modern day central and southern Kerala. The colonial policies, which isolated British Malabar from Travancore and Cochin, as well as several social and cultural factors adversely affected the general and health care infrastructure developments in the colonial Malabar region. Compared to Madras Presidency, Travancore seems to have paid greater attention to the health of its people. Providing charity to its people through medical relief was regarded as one of the main functions of the state. -

Travancore-Cochin Integration; a Model to Native States of India

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology ISSN No : 1006-7930 Travancore-Cochin Integration; A model to Native states of India Dr Suresh J Assistant Professor, Department Of History University College, Thiruvanathapuram Kerala University Abstract The state of Kerala once remained as an integral part of erstwhile Tamizakaom. Towards the beginning of the modern age this political terrain gradually enrolled as three native kingdoms with clear cut boundaries. The three native states comprised kingdom of Travancore of kingdom of Cochin, kingdom of Calicut These territories never enjoyed a single political structure due to the internal and foreign interventions. Travancore and Cochin were neighboring states enjoyed cordial relations. The integration of both states is a unique event in the history of India as well as History of Kerala. The title of Rajapramukh and the administrative division of Dewaswam is unique aspect in the course of History. Keywords Rajapramukh , Dewaswam , Panjangam, Yogam, annas, oorala, Melkoima Introduction The erstwhile native state of Travancore and Cochin forms political unity of Indian sub- continent through discussions debates and various agreements. The states situating nearby maintained interstate reactions in various realms. At occasionally they maintained cordial relation on the other half hostile in every respect. In different epochs the diplomatic relations of both the state were unique interns of political economic, social and cultural aspects. This uniqueness ultimately enabled both the state to integrate them ultimate into the concept of the formation of the state of Kerala. The division of power in devaswams and assumed the title Rajapramukh is unique chapters in Kerala as well as Indian history Volume XII, Issue VII, 2020 Page No: 128 Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology ISSN No : 1006-7930 Scope and relevance of Study Travancore and Cochin the native states of southern kerala. -

Travancore Medical College

Travancore Medical College https://www.indiamart.com/company/9403426/ Travancore Medical College Hospital, functioning in Kollam Medi City is a unit under the Quilon Medical trust. TMCH is ISO 9001: 2008 certified and spread over 98 acres of land. The hospital is facilitated with 850 bedded and is a ... About Us Travancore Medical College Hospital, functioning in Kollam Medi City is a unit under the Quilon Medical trust. TMCH is ISO 9001: 2008 certified and spread over 98 acres of land. The hospital is facilitated with 850 bedded and is a multi-specialty hospital equipped with state-of-the-art equipment providing end-to-end treatment in the field of almost all branches of Medicine. The Medical College is provided with a most advanced level for all super-specialty units and colleges for medical and nursing courses. The campus is half a kilometer away from NH-47 (Kollam-Thiruvananthapuram portion). Kollam Medicity stands as the nerve center in medical field, located in midst of Kollam-Kerala with a lovely ambiance apart from the crowded city life. The best approach to patients with the best modern medical facilities at reasonable rate highlighted the hospital since its establishment in 2009. Our focus on professional excellence and community engagement draws an increasing number of patients, bright students and technicians to our campus.Travancore Medical College is a gang up of a diverse team of doctors, nursing staff, allied health professionals, teachers, researchers and administrators, from highly experienced to the young and enthusiastic, comprising of the finest healthcare professionals in the region. It is our belief that access to better and quality healthcare can deliver outstanding benefits to all stakeholders in the larger community we serve. -

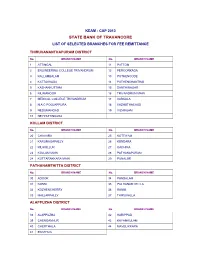

State Bank of Travancore List of Selected Branches for Fee Remittance

KEAM : CAP 2013 STATE BANK OF TRAVANCORE LIST OF SELECTED BRANCHES FOR FEE REMITTANCE THIRUVANANTHAPURAM DISTRICT No. BRANCH NAME No. BRANCH NAME 1 ATTINGAL 11 PATTOM 2 ENGINEERING COLLEGE TRIVANDRUM 12 PEROORKADA 3 KALLAMBALAM 13 POTHENCODE 4 KATTAKKADA 14 PUTHENCHANTHAI 5 KAZHAKKUTTAM 15 SANTHINAGAR 6 KILIMANOOR 16 TRIVANDRUM MAIN 7 MEDICAL COLLEGE TRIVANDRUM 17 VARKALA 8 N A C POOJAPPURA 18 VAZHUTHACAUD 9 NEDUMANGAD 19 VIZHINJAM 10 NEYYATTINKARA KOLLAM DISTRICT No. BRANCH NAME No. BRANCH NAME 20 CHAVARA 25 KOTTIYAM 21 KARUNAGAPALLY 26 KUNDARA 22 KILIKOLLUR 27 OACHIRA 23 KOLLAM MAIN 28 PATHANAPURAM 24 KOTTARAKKARA MAIN 29 PUNALUR PATHANAMTHITTA DISTRICT No. BRANCH NAME No. BRANCH NAME 30 ADOOR 34 PANDALAM 31 KONNI 35 PATHANAMTHITTA 32 KOZHENCHERRY 36 RANNI 33 MALLAPPALLY 37 THIRUVALLA ALAPPUZHA DISTRICT No. BRANCH NAME No. BRANCH NAME 38 ALAPPUZHA 42 HARIPPAD 39 CHENGANNUR 43 KAYAMKULAM 40 CHERTHALA 44 MAVELIKKARA 41 EDATHUA KOTTAYAM DISTRICT No. BRANCH NAME No. BRANCH NAME 45 ANTHINAD 54 MANIMALA 46 CHANGANASSERRY MAIN 55 MEDICAL COLLEGE KOTTAYAM 47 CHINGAVANAM 56 PALA 48 C M S COLLEGE KOTTAYAM 57 PAMPADY 49 ETTUMANOOR 58 PUTHUPALLY 50 KADUTHURUTHY 59 THALAYOLAPARAMBU 51 KANJIKUZHY 60 UZHAVOOR 52 KANJIRAPALLY 61 VAIKOM 53 KOTTAYAM MAIN 62 VAKATHANAM IDUKKI DISTRICT No. BRANCH NAME No. BRANCH NAME 63 IDUKKI 67 NEDUMKANDAM 64 KATTAPPANA 68 PEERUMEDU 65 KUMILY 69 THODUPUZHA 66 MUNNAR 70 VANDIPERIYAR ERNAKULAM DISTRICT No. BRANCH NAME No. BRANCH NAME 71 ALUVA 78 KOTHAMANGALAM 72 ANGAMALI 79 MG ROAD ERNAKULAM 73 EDAPPALLY 80 MUVATTUPUZHA 74 KAKKANAD CIVIL STATION 81 PANAMPALLY NAGAR 75 KALAMASSERRY MAIN 82 PERUMBAVOOR 76 KOCHI 83 TRIPPUNITHURA 77 KOOTHATTUKULAM THRISSUR DISTRICT No. -

Hunting of Endemic and Threatened Forest-Dwelling Chelonians in the Western Ghats, India

Asian Journal of Conservation Biology, December 2013. Vol. 2 No. 2, pp. 172–177 AJCB: SC0012 ISSN 2278-7666 ©TCRP 2013 Hunting of endemic and threatened forest-dwelling chelonians in the Western Ghats, India a,* a Arun Kanagavel and Rajeev Raghavan aConservation Research Group (CRG), St. Albert’s College, Kochi, 682 018, Kerala, India. (Accepted November 25, 2013) ABSTRACT This study investigates the hunting of two endemic and threatened terrestrial chelonians, the Cochin forest cane turtle (Vijayachelys silvatica) and Travancore tortoise (Indotestudo travancorica) in the Western Ghats region of India. Informal interviews were conducted with indigenous and non-indigenous communities and Forest De- partment officials to understand the dynamics of chelonian hunting and the existent rationale and beliefs that supported it. Chelonian consumption was existent among both indigenous and non-indigenous communities, but was higher among the former. Indotestudo travancorica was exploited to a larger extent than Vijayachelys silvatica. Both the species were used as a cure for piles and asthma, to increase body strength and were largely captured during collection of non-timber forest produce and fire management activities. These chelonians were also sold to local hotels and served to customers known on a personal basis with minimal transfer to urban ar- eas. Conservation action needs to be prioritised towards I. travancorica, by upgrading its IUCN Red List status, and also through increased interaction between the Forest Department and local communities to improve che- lonian conservation in the landscape. Key words: Indotestudo travancorica, Kerala, Vijayachelys silvatica; Wild meat INTRODUCTION comprises numerous forest-dwelling communities, po- tentially means that wild species are being used at a Hunting is a primary threat to biodiversity worldwide that large scale. -

Nature Watch a Tale of Two Turtles

FEATURE ARTICLE Nature Watch A Tale of Two Turtles V Deepak Turtles are one of the oldest groups of reptiles in the world and India has a large and diverse assemblage of extant turtles. While the North and Northeast parts of India are higher in turtle diversity, peninsular India has all the three endemic turtles. The Cane turtle and the Travancore tortoise are two endemic forest dwelling turtles. Until recently, very little was known about the ecology of these two turtles. I spent five years V Deepak is a postdoctoral during my PhD studying their behaviour and ecology in the fellow at the Centre for Ecological Sciences, IISc. Western Ghats. In this article, I share general information on He is interested in ecology, evolution of turtles and some of my findings on the behaviour systematics and biogeogra- and ecology of these two endemic turtles of India. phy of amphibians and reptiles in India. His Introduction current research focuses on systematics and Turtles have existed on Earth since the rise of Dinosaurs. The phylogeography of fan- oldest known turtle fossil with a complete shell is of the throated lizards (Sitana) in the Indian subcontinent. Proganochelys species dating from the late Triassic (220 Ma). He uses morphological and The shell of a turtle is a unique and successful body plan which molecular data to has enabled them to survive over 200 million years despite understand evolutionary fluctuating climates and diverse forms of vertebrate predators. relationships and distribution patterns of 1 Many living tortoises are slow growing and attain sexual matu- different groups of rity quite late.