FIELD BULLETIN Perspectives on Chhetri Identity and How These Relate to Federalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Berkeley Room One Thousand

UC Berkeley Room One Thousand Title Kingship, Buddhism and the Forging of a Region Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8vn4g2jd Journal Room One Thousand, 3(3) ISSN 2328-4161 Author Hawkes, Jason Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Jason Hawkes Kingship, Buddhism and the MedievalForging Pilgrimage of a inRegion West Nepal West Nepal provides a unique space to think about pilgrimage in the past. For many centuries, this central Himalayan region lay at the fringes of neighboring states. During the 13th century CE, the Khasa Malla dynasty established a kingdom here with seasonal capitals at Sinja and Dullu, which soon grew to encompass the entire region as well as parts of India and Tibet (Adhikary 1997; Pandey 1997) (Figure 1). With these developments, the region became a key zone of interaction. Capitalizing on pre-existing routes and connections, it connected India to the Silk Road, and provided a conduit for the spread and survival of Indian Buddhism. Pilgrimage would have been an important component of the movement of people and ideas within and across the region— interactions that shaped the socio-cultural and economic dynamics of the area. However, due to its liminal position, the study of West Nepal has been neglected in favor of more ‘important’ neighboring regions. As such, we have only n outline understanding of pilgrimage and the societal framework within which it took place. The monuments built during the reign of the Khasa Malla provide tantalizing clues that can be used to study pilgrimage and the movement Figure 1 243 Jason Hawkes of people and ideas in the Himalaya. -

Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-Kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L

Western Washington University Western CEDAR A Collection of Open Access Books and Books and Monographs Monographs 2008 Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L. Curley Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks Part of the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Curley, David L., "Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal" (2008). A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs. 5. https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Books and Monographs at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents Acknowledgements. 1. A Historian’s Introduction to Reading Mangal-Kabya. 2. Kings and Commerce on an Agrarian Frontier: Kalketu’s Story in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 3. Marriage, Honor, Agency, and Trials by Ordeal: Women’s Gender Roles in Candimangal. 4. ‘Tribute Exchange’ and the Liminality of Foreign Merchants in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 5. ‘Voluntary’ Relationships and Royal Gifts of Pan in Mughal Bengal. 6. Maharaja Krsnacandra, Hinduism and Kingship in the Contact Zone of Bengal. 7. Lost Meanings and New Stories: Candimangal after British Dominance. Index. Acknowledgements This collection of essays was made possible by the wonderful, multidisciplinary education in history and literature which I received at the University of Chicago. It is a pleasure to thank my living teachers, Herman Sinaiko, Ronald B. -

THE DEVADASI SYSTEM: Temple Prostitution in India

UCLA UCLA Women's Law Journal Title THE DEVADASI SYSTEM: Temple Prostitution in India Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/37z853br Journal UCLA Women's Law Journal, 22(1) Author Shingal, Ankur Publication Date 2015 DOI 10.5070/L3221026367 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California THE DEVADASI SYSTEM: Temple Prostitution in India Ankur Shingal* Introduction Sexual exploitation, especially of children, is an internation- al epidemic.1 While it is difficult, given how underreported such crimes are, to arrive at accurate statistics regarding the problem, “it is estimated that approximately one million children (mainly girls) enter the multi-billion dollar commercial sex trade every year.”2 Although child exploitation continues to persist, and in many in- stances thrive, the international community has, in recent decades, become increasingly aware of and reactive to the issue.3 Thanks in large part to that increased focus, the root causes of sexual exploita- tion, especially of children, have become better understood.4 While the issue is certainly an international one, spanning nearly every country on the globe5 and is one that transcends “cul- tures, geography, and time,” sexual exploitation of minors is perhaps * J.D., Class of 2014, University of Chicago Law School; B.A. in Political Science with minor in South Asian Studies, Class of 2011, University of Califor- nia, Los Angeles. Currently an Associate at Quinn Emanuel Urquhart and Sul- livan, LLP. I would like to thank Misoo Moon, J.D. 2014, University of Chicago Law School, for her editing and support. 1 Press Release, UNICEF, UNICEF calls for eradication of commercial sexual exploitation of children (Dec. -

LCSH Section K

K., Rupert (Fictitious character) Motion of K stars in line of sight Ka-đai language USE Rupert (Fictitious character : Laporte) Radial velocity of K stars USE Kadai languages K-4 PRR 1361 (Steam locomotive) — Orbits Ka’do Herdé language USE 1361 K4 (Steam locomotive) UF Galactic orbits of K stars USE Herdé language K-9 (Fictitious character) (Not Subd Geog) K stars—Galactic orbits Ka’do Pévé language UF K-Nine (Fictitious character) BT Orbits USE Pévé language K9 (Fictitious character) — Radial velocity Ka Dwo (Asian people) K 37 (Military aircraft) USE K stars—Motion in line of sight USE Kadu (Asian people) USE Junkers K 37 (Military aircraft) — Spectra Ka-Ga-Nga script (May Subd Geog) K 98 k (Rifle) K Street (Sacramento, Calif.) UF Script, Ka-Ga-Nga USE Mauser K98k rifle This heading is not valid for use as a geographic BT Inscriptions, Malayan K.A.L. Flight 007 Incident, 1983 subdivision. Ka-houk (Wash.) USE Korean Air Lines Incident, 1983 BT Streets—California USE Ozette Lake (Wash.) K.A. Lind Honorary Award K-T boundary Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary UF Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) K.A. Linds hederspris K-T Extinction Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction BT National parks and reserves—Hawaii K-ABC (Intelligence test) K-T Mass Extinction Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) USE Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-B Bridge (Palau) K-TEA (Achievement test) Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Koro-Babeldaod Bridge (Palau) USE Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-BIT (Intelligence test) K-theory Ka-ju-ken-bo USE Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test [QA612.33] USE Kajukenbo K. -

Mise En Page 1

ASIA PACIFIC NEPAL FEDERAL COUNTRY BASIC SOCIO-ECONOMIC INDICATORS INCOME GROUP: LOW INCOME LOCAL CURRENCY: NEPALESE RUPEE (NPR) POPULATION AND GEOGRAPHY ECONOMIC DATA Area: 147 180 km 2 GDP: 79 billion (current PPP international dollars), 2 697 dollars per inhabitant (2017) Population: 29.305 million inhabitants (2017), an increase of 1.2% Real GDP growth: 7.5 % (2017 vs 2016) per year (2010-2015) Unemployment rate: 2.7 % (2017) Density: 199 inhabitants / km 2 Foreign direct investment, net inflows (FDI): 196 (BoP, current USD millions, 2017) Urban population: 19.3 % of national population Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF): 34% of GDP (2017) Urban population growth: 3.2 % (2017 vs 2016) HDI: 0.574 (medium), ranking 149 (2017) Capital city: Kathmandu (4.5 % of national population) Poverty rate: 15% (2010) MAIN FEATURES OF THE MULTI-LEVEL GOVERNANCE FRAMEWORK Following the end in 2006 of a decade-long civil war, Nepal’s governance framework is currently in the transition from being a Monarchy to a multiparty democratic republic. With the promulgation of the new Constitution in 2015, Nepal moved from a unitary form of government to a federal one with a strong focus on decentralization based on “cooperative federalism”. The new federation has three tiers of government, namely federal, state and local, whereby powers shall be exercised pursuant to the Constitution and the state laws. The Constitution has assigned both exclusive and concurrent powers, to be jointly exercised by the federal and the state levels or jointly by all three tiers of government. The jurisdiction of the local governments is outlined under Schedule 8 of the Constitution, which establishes that local governments are responsible for development activities and for mobilizing the necessary resources to carry out such activities. -

Cultural Crisis of Caste Renouncer: a Study of Dasnami Sanyasi Identity in Nepal

Molung Educational Frontier 91 Cultural Crisis of Caste Renouncer: A Study of Dasnami Sanyasi Identity in Nepal Madhu Giri* Abstract Jat NasodhanuJogikois a famous mocking proverb to denote the caste status of Sanyasi because the renouncer has given up traditional caste rituals set by socio-cultural institutions. In other cultural terms, being Sanyasi means having dissociation himself/herself with whatever caste career or caste-based social rank one might imagine. To explore the philosophical foundation of Sanyasi, they sacrificed caste rituals and fire (symbol of power, desire, and creation). By the virtues of sacrifice, Sanyasi set images of universalism, higher than caste order, and otherworldly being. Therefore, one should not ask the renouncer caste identity. Traditionally, Sanyasi lived in Akhada or Matha,and leadership, including ownership of the Matha transformed from Guru to Chela. On the contrary, DasnamiMahanta started marital and private life, which is paradoxical to the philosophy of Sanyasi.Very few of them are living in Matha,but the ownership of the property of Mathatransformed from father to son. The land and property of many Mathas transformed from religious Guthi to private property. In terms of cultural practices, DasnamiSanyasi adopted high caste culture and rituals in their everyday life. Old Muluki Ain 1854 ranked them under Tagadhari, although they did notassert twice-born caste in Nepal. Central Bureau of Statistics, including other government institutions of Nepal, listed Dasnamiunder the line ofChhetri and Thakuri. The main objective of the paper is to explore the transformation of Dasnami institutional characteristics and status from caste renunciation identity to caste rejoinder and from images of monasticism, celibacy, universalism, otherworldly orientation to marital, individualistic lay life. -

Country Poverty Analysis (Detailed) Nepal

Country Poverty Analysis (Detailed) Nepal Country Partnership Strategy: Nepal, 2013–20172013-2017 COUNTRY POVERTY ANALYSIS: NEPAL A. Background 1. This country poverty analysis draws mainly on the National Living Standards Surveys (NLSS), which was first conducted in 1996, and carried out again in 2004 and 2011. 1 The NLSS estimates the national poverty line following the cost of basic needs approach, which is the expenditure value in local currency required to fulfill both food and non food basic needs. The NLSS III findings can be disaggregated into fourteen analytical domains (mountains, urban- Kathmandu, urban-hill, urban-terai, eastern rural hills, rural central hills, rural western hills, rural mid- and far-western hills, rural eastern terai, rural central terai, rural western terai, and rural mid- and far-western terai. This analysis also draws from the Nepal Demographic Health Survey (2011) and the Census (2011) for information on health and access to basic services. B. Income Poverty and its Distribution 2. Using the national poverty line, poverty incidence has been falling at an accelerated pace from 41.8% to 30.9% between 1996 and 2004 and further to 25.2% of the overall population in 2011. This remarkable decline occurred in the backdrop of a significant increase in the national poverty line from NRs7,696 per capita per year in 2004 to NRs19,261 per capita per year in 2011 to account for a higher quality consumption pattern . 3. Using international poverty line of $1.25 per day, the incidence of poverty has declined steadily from 68.0% in 1996 to 53.1% in 2004 and 24.8% in 2011. -

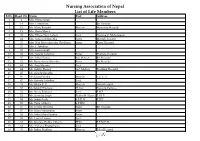

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No

Nursing Association of Nepal List of Life Members S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 1 2 Mrs. Prema Singh 2 14 Mrs. I. Mathema Bir Hospital 3 15 Ms. Manu Bangdel Matron Maternity Hospital 4 19 Mrs. Geeta Murch 5 20 Mrs. Dhana Nani Lohani Lect. Nursing C. Maharajgunj 6 24 Mrs. Saraswati Shrestha Sister Mental Hospital 7 25 Mrs. Nati Maya Shrestha (Pradhan) Sister Kanti Hospital 8 26 Mrs. I. Tuladhar 9 32 Mrs. Laxmi Singh 10 33 Mrs. Sarada Tuladhar Sister Pokhara Hospital 11 37 Mrs. Mita Thakur Ad. Matron Bir Hospital 12 42 Ms. Rameshwori Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 13 43 Ms. Anju Sharma Lect. 14 44 Ms. Sabitry Basnet Ast. Matron Teaching Hospital 15 45 Ms. Sarada Shrestha 16 46 Ms. Geeta Pandey Matron T.U.T. H 17 47 Ms. Kamala Tuladhar Lect. 18 49 Ms. Bijaya K. C. Matron Teku Hospital 19 50 Ms.Sabitry Bhattarai D. Inst Nursing Campus 20 52 Ms. Neeta Pokharel Lect. F.H.P. 21 53 Ms. Sarmista Singh Publin H. Nurse F. H. P. 22 54 Ms. Sabitri Joshi S.P.H.N F.H.P. 23 55 Ms. Tuka Chhetry S.P.HN 24 56 Ms. Urmila Shrestha Sister Bir Hospital 25 57 Ms. Maya Manandhar Sister 26 58 Ms. Indra Maya Pandey Sister 27 62 Ms. Laxmi Thakur Lect. 28 63 Ms. Krishna Prabha Chhetri PHN F.P.M.C.H. 29 64 Ms. Archana Bhattacharya Lect. 30 65 Ms. Indira Pradhan Matron Teku Hospital S.No. Regd. No. Name Post Address 31 67 Ms. -

Nepal, November 2005

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Nepal, November 2005 COUNTRY PROFILE: NEPAL November 2005 COUNTRY Formal Name: Kingdom of Nepal (“Nepal Adhirajya” in Nepali). Short Form: Nepal. Term for Citizen(s): Nepalese. Click to Enlarge Image Capital: Kathmandu. Major Cities: According to the 2001 census, only Kathmandu had a population of more than 500,000. The only other cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants were Biratnagar, Birgunj, Lalitpur, and Pokhara. Independence: In 1768 Prithvi Narayan Shah unified a number of states in the Kathmandu Valley under the Kingdom of Gorkha. Nepal recognizes National Unity Day (January 11) to commemorate this achievement. Public Holidays: Numerous holidays and religious festivals are observed in particular regions and by particular religions. Holiday dates also may vary by year and locality as a result of the multiple calendars in use—including two solar and three lunar calendars—and different astrological calculations by religious authorities. In fact, holidays may not be observed if religious authorities deem the date to be inauspicious for a specific year. The following holidays are observed nationwide: Sahid Diwash (Martyrs’ Day; movable date in January); National Unity Day and birthday of Prithvi Narayan Shah (January 11); Maha Shiva Ratri (Great Shiva’s Night, movable date in February or March); Rashtriya Prajatantra Diwash (National Democracy Day, movable date in February); Falgu Purnima, or Holi (movable date in February or March); Ram Nawami (Rama’s Birthday, movable date in March or April); Nepali New Year (movable date in April); Buddha’s Birthday (movable date in April or May); King Gyanendra’s Birthday (July 7); Janai Purnima (Sacred Thread Ceremony, movable date in August); Children’s Day (movable date in August); Dashain (Durga Puja Festival, movable set of five days over a 15-day period in September or October); Diwali/Tihar (Festival of Lights and Laxmi Puja, movable set of five days in October); and Sambhidhan Diwash (Constitution Day, movable date in November). -

Some Notes on Nepali Castes and Sub-Castes—Jat and Thar

SOME NOTES ON NEPALI CASTES AND SUB-CASTES- JAT AND THAR. - Suresh Singh This paper attempts to make a re-presentation of evolution and construction of Jat and Thar system among the Parbatya or hill people of Nepal. It seeks to expose the reality behind the myth that the large number of Aryans migrated from Indian plains due to Muslim invasion and conquered to become the rulers in Nepal, and the Mongoloids were the indigenous people. It also seeks to show the construction and reconstruction of identity of the different castes (Jats) and subcastes (Thars). The Nepalese history is lost in legends and fables. Archaeological data, which might shed light on the early years, are practically nonexistent or largely unexplored, because the Nepalese Government has not encouraged such research within its borders. However, there seem to be a number of sites that might yield valuable find, once proper excavation take place. Another problem seems to be that history writing is closely connected with the traditional conception of Nepali historiography, constructed and intervened by the efforts of the ruling elite. Many of the written documents have been re-presented to legitimatize the ruling elite’s claim to power. As it is well known from political history, the social history, too, becomes an interpretation from the view of the Kathmandu valley, and from the Indian or alleged Indian immigrants and priestly class. It is difficult to imagine, that Aryans came to Nepal in greater numbers about 600 years ago, and because of their mental superiority and their noble character, they were asked by the people to become the rulers of their small states. -

In Nepal : Citizens’ Perspectives on the Rule of Law and the Role of the Nepal Police

Calling for Security and Justice in Nepal : Citizens’ Perspectives on the Rule of Law and the Role of the Nepal Police Author Karon Cochran-Budhathoki Editors Shobhakar Budhathoki Nigel Quinney Colette Rausch With Contributions from Dr. Devendra Bahadur Chettry Professor Kapil Shrestha Sushil Pyakurel IGP Ramesh Chand Thakuri DIG Surendra Bahadur Shah DIG Bigyan Raj Sharma DIG Sushil Bar Singh Thapa Printed at SHABDAGHAR OFFSET PRESS Kathmandu, Nepal United States Institute of Peace National Mall at Constitution Avenue 23rd Street NW, Washington, DC www.usip.org Strengthening Security and Rule of Law Project in Nepal 29 Narayan Gopal Marg, Battisputali Kathmandu, Nepal tel/fax: 977 1 4110126 e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] © 2011 United States Institute of Peace All rights reserved. © 2011 All photographs in this report are by Shobhakar Budhathoki All rights reserved. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily refl ect the views of the United States Institute of Peace. CONTENTS Foreword by Ambassador Richard H. Solomon, President of the United States Institute of Peace VII Acknowledgments IX List of Abbreviations XI Chapter 1 Summary 1.1 Purpose and Scope of the Survey 3 1.2 Survey Results 4 1.2.1 A Public Worried by Multiple Challenges to the Rule of Law, but Willing to Help Tackle Those Challenges 4 1.2.2 The Vital Role of the NP in Creating a Sense of Personal Safety 4 1.2.3 A Mixed Assessment of Access to Security 5 1.2.4 Flaws in the NP’s Investigative Capacity Encourage “Alternative -

The Caste System

Name ______________________________ Mod ____ Global Studies Ms. Pojer HGHS The caste system In ancient India, society was organized so that each specialized job was performed by a specific group, or caste. The interdependence of all of the various castes was recognized, and each one was considered necessary to the society as a whole. In the earliest known mention of caste, perhaps dating from about 1000 B.C.E., the metaphor (symbol) of the human body was used to describe Indian society. This metaphor stresses the idea of hierarchy as well as that of interdependence. The brahman, or priestly, caste represents society's head; the kshatriya, or warrior, caste are its arms; the vaishya caste—traders and landowners—are the legs; and the sudra caste—the servants of the other three—are the feet. These four castes—brahman, kshatriya, vaishya, and sudra—are the classical four divisions of Hindu society. In practice, however, there have always been many subdivisions (J'atis) of these castes. 1. THE FOUR VARNA: The word caste comes from the Portuguese word castas, meaning "pure." This Portuguese word expresses one of the most central values of Indian society: the idea of ritual purity. In India, however, the word varna, or "color," denotes the fourfold division of Indian society. The word varna may have been used because each of the four castes was assigned a specific color as its emblem. In Hindu religious texts, the dharma—the law, or duty—of each varna is described. It was thought that this dharma was an inherited, or inborn, quality. Consequently, people thought that if intermarriages took place, there would be much confusion as to the dharma of the next generation of children.