Portuguese Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inside Africa

INSIDE AFRICA 17 February 2017 Now is the time to invest in Africa BRIEFS Africa • G20 foreign ministers to tackle fight against poverty in Africa • West African CFA franc zone to see strong growth, increased CONTENTS risks: IMF • Ecobank CEO wants 100 mln customers by 2020 In-Depth: Angola - Africa can become a global economic powerhouse. This is • Angola's economy contracted 4.3 percent in Q3, 2016 - stats how .......................................................................................... 2 agency • - Making Renewable Energy More Accessible in Sub-Saharan Angola inflation slows to 40.4 percent year/year in January • Non-resident investors will be able to invest in Angola Stock Africa ................................................................................. 3 Exchange • IMF, WORLD BANK& AFDB ................................................... 5 Eni starts production of East Pole field in Angola - state oil firm • INVESTMENTS ........................................................................... 8 Angola’s Endiama negotiates financing for another diamond project BANKING Egypt • Banks ....................................................................................................... 10 Italy's Eni to start production in Egypt by end of year Ivory Coast Markets 11 .................................................................................................... • Ivory Coast consumer inflation rises to 1.1 pct yr/yr in January ENERGY .................................................................................... -

GIPE-011123-Contents.Pdf (1.391Mb)

THE PROBLEM OF INTERNATIONAL INVESTMENT The .Riiyal I ...tiIIute oj Intemalional Affairs i8 _ ..""jftcial tJnrl """.po!ilicaZ body,Joon.dtd ... 1920 to .....",..,.ag. tJnrl Jat>iZital. Ike 8cientific 8ttu% oj intemalionaZ qu<8t1of18. The 11l81i1ut., ... BUCh, i8 precluded by;u rvlu from upruring an opinion 011 any CUlpect oJ...,.,.• ....eionaZ "ffaVr8; opinionB upru.ed ... 1MB book or.. /hereJor., pur'11I indWiduoZ. THE PROBLEM OF INTERNATIONAL • INVESTMENT . A Report by a Study Group of Members of the Royal Institute of International Mairs OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON NEW YORK TORONTO 1 __ -urIM .....,.;_ ~IM R'¥IlI"- ~I-.. ..... -'~ 1937 ODORD UNIVERSITY PRBSS AMBN ROUBH, B.C. 4 London Bdlnbmgb Glalgow New York 'l'OlOIlto Melbourne Capetown Bomb., Calcutta Madru HUIIPHREY IIILII'ORD PVBLIBBBB W nm VIn'D8lfl' XbSZ;-. \.N3t &7 /1 ( 2.. J FOREWORD TIm Council of the Royal Institute of International Affairs believe that this a.ddition to the series of Study Group Reports will fill an important gap in the literature of international economics. It is an attempt, in the first ple.ce, to e.na.lyse objectively the conditions under which long-term oapital may move between countries and to consider oe.refully the speoie.l fe.otors in the world economy of to-day which tend to limit the extent to which such movements e.re possible or desirable. Secondly, the book contains a careful study of the post war history of international investments which brings together facts and figures whioh e.re ine.ocessible to most students and business men. The Council is indebted to the following group of members of the Institute for the preparation of the Report: Mr. -

Ceramics in Portuguese Architecture (16Th-20Th Centuries)

CASTELLÓN (SPAIN) CERAMICS IN PORTUGUESE ARCHITECTURE (16TH-20TH CENTURIES) A. M. Portela, F. Queiroz Art Historians - Portugal [email protected] ABSTRACT The purpose of this paper is to present a synoptic view of the evolution of Portuguese architectural ceramics, particularly focusing on the 19th and 20th centuries, because the origins of current uses of ceramic tiles in Portuguese architecture stem from those periods. Thus, the paper begins with the background to the use of ceramics in Portuguese architecture, between the 16th and 18th centuries, through some duly illustrated paradigmatic examples. The study then presents examples of the 19th century, in a period of transition between art and industry, demonstrating the diversity and excellence of Portuguese production, as well as the identifying character of the phenomenon of façade tiling in the Portuguese urban image. The study concludes with a section on the causes of the decline in the use of ceramic materials in Portuguese architecture in the first decades of the 20th century, and the appropriation of ceramic tiling by the popular classes in their vernacular architecture. Parallel to this, the paper shows how the most erudite route for ceramic tilings lay in author works, often in public buildings and at the service of the nationalistic propaganda of the dictatorial regime. This section also explains how an industrial upgrading occurred that led to the closing of many of the most important Portuguese industrial units of ceramic products for architecture, foreshadowing the current ceramic tiling scenario in Portugal. 1 CASTELLÓN (SPAIN) 1. INTRODUCTION In Portugal, ornamental ceramics used in architecture are generally - and almost automatically - associated only with tiles, even though, depending on the historical period, one can enlarge considerably the approach, beyond this specific form of ceramic art. -

The World Bank

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Ca- ZC~ / 3 7 Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. 7630-BO STAFF APPRAISALREPORT Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLICOF BOLIVIA MINING SECTORREHABILITATION PROJECT APRIL 17, 1989 Public Disclosure Authorized Industry,Trade and FinanceOperations Division Country DepartmentIII Public Disclosure Authorized Latin America and the CaribbeanRegion This document hasa resticted dsibuto0vand may be used by oenpienlsoly In the perdonnanoe of their official duties. Its contents may - A otherwise be disclosed wt World Bank authorizatin CURRENCYEQUIVALENTS Currency Name - Boliviano US$1.00 - Bolivianos 2.47 Bolivianos 1.00 - US$0.405 FISCAL YEAR January 1 to December 31 WEIGHTS AND MEASURES 1 meter (m) G 3.281 feet (ft) 1 kilometer (km) = 0.622 miles (mi) 1 kilogram (kg) 2.205 pounds (lb) 1 troy ounce (troy oz) - 31.: grams 1 gram (g) - .032 troy ox 1 metric tonne (mt) - S2,151 troy oz | 2.205 lbs 1 short ton (T) - 2,000 lbs PRINCIPAL ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS BAMIN - Banco Minero BCB - Banco Central de Bolivia SA - Banco Industrial SA . - Centro de Investigacion Minero Metalurgica IMITBOL - Corporacion Hinera de Bolivia -'D - Development Credit Department (Central Bank) ,TAW - Empresa Nacional de Fundiciones FCNEM - Fondo Nacional de Exploracion Minera FSE - Fondo Social de Emergencia FSTMN - Federacion Sindical de Trabajadores Mineros de Bolivia GEOBOL - Servicio Geologico de Bolivia IDB - Interamerican Developi*ent Bank IDM - Instituto de Desarrollo Minero INK - Instituto de Investigacion Minero Metalurgica MMK - Ministry of Mining and Metallurgy STCM - Servicio Tecnico del Cadastro Minero FOR OMFCIL USE ONLY STAFF APPRAISAL REPORT BOLIVIA MINING SECTOR REHABILITATION PROJECT TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. -

Sponsored by the Department of Science and Technology Volume

Volume 26 Number 3 • August 2015 Sponsored by the Department of Science and Technology Volume 26 Number 3 • August 2015 CONTENTS 2 Reliability benefit of smart grid technologies: A case for South Africa Angela Masembe 10 Low-income resident’s preferences for the location of wind turbine farms in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa Jessica Hosking, Mario du Preez and Gary Sharp 19 Identification and characterisation of performance limiting defects and cell mismatch in photovoltaic modules Jacqui L Crozier, Ernest E van Dyk and Frederick J Vorster 27 A perspective on South African coal fired power station emissions Ilze Pretorius, Stuart Piketh, Roelof Burger and Hein Neomagus 41 Modelling energy supply options for electricity generations in Tanzania Baraka Kichonge, Geoffrey R John and Iddi S N Mkilaha 58 Options for the supply of electricity to rural homes in South Africa Noor Jamal 66 Determinants of energy poverty in South Africa Zaakirah Ismail and Patrick Khembo 79 An overview of refrigeration and its impact on the development in the Democratic Republic of Congo Jean Fulbert Ituna-Yudonago, J M Belman-Flores and V Pérez-García 90 Comparative bioelectricity generation from waste citrus fruit using a galvanic cell, fuel cell and microbial fuel cell Abdul Majeed Khan and Muhammad Obaid 100 The effect of an angle on the impact and flow quantity on output power of an impulse water wheel model Ram K Tyagi CONFERENCE PAPERS 105 Harnessing Nigeria’s abundant solar energy potential using the DESERTEC model Udochukwu B Akuru, Ogbonnaya -

Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro, a Portuguese Art Nouveau Artist Rita Nobre Peralta, Leonor Da Costa Pereira Loureiro, Alice Nogueira Alves

Strand 2. Art Nouveau and Politics in the Dawn of Globalisation Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro, a portuguese Art Nouveau artist Rita Nobre Peralta, Leonor da Costa Pereira Loureiro, Alice Nogueira Alves Abstract The Art Nouveau gradual appearance in the Portuguese context it’s marked by the multidimensional artist Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro, and by his audacious affirmation as an avant- garde figure focused upon the industrial modernity, that is able to highlight some of the most original artistic solutions of his time. He manages to include in his production a touch of Portuguese Identity alongside with the new European trends of the late 19th century, combining traditional production techniques, themes and typologies, which are extended to artistic areas as varied as the press, the decorative arts and the decoration of cultural events. In this article, we pretend to analyse some of his proposals within Lisbon's civil architecture interior design and his participation in the Columbian Exhibition, held in Madrid in 1892, where he was a member of the Portuguese Legation, co-responsible for the selection and composition of the exhibition contents. Keywords: Art Nouveau, Cultural heritage, Portuguese identity, 19 th Century, interior and exterior design, Decorative arts, ceramics, tiles, furniture, Colombian Exposition of Madrid 1892 1 THE FIRST YEARS - PRESS, HUMOR AND AVANT-GARDE Rafael Augusto Prostes Bordalo Pinheiro (1846-1905) was born on March 21, 1846, in Lisbon, Portugal. His taste for art has always been boosted up by his father, Manuel Maria Bordalo Pinheiro who, together with his occupation as a civil servant, was also known as a painter and an external student of the Academy of Fine Arts of Lisbon. -

2017 the 2017 Paris Biennial

THE 2017 PARIS BIENNIAL THE GRAND PALAIS FROM MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 11 THROUGH SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 17 2017 THE PROGRAM PRESS RELEASE — PARIS, MAY 15, 2017 THE BIENNALE PARIS PRESS RELEASE — PARIS, MAY 15, 2017 2 THE 2017 PARIS BIENNIAL NEW DATES TO ADAPT TO THE ANNUALIZATION OF THE PARIS BIENNIAL The Paris Biennial will be held from Monday, September 11 to Sunday, September 17, 2017 Vernissage: Sunday, September 10, 2017 With the announcement of its annualization, The Paris Biennial confirms its commitment to renewal and development, adopting a shorter, more dynamic format, while offering two potential weekends to French and international collectors and professionals. A CULTURAL AND ARTISTIC BACK-TO-SCHOOL WEEK IN 2017 The Paris Biennial also wishes to support and encourage the development of a more compelling cultural and artistic program to accompany Back-to-School Week. Ultimately, it is the idea of a week of artistic excellence that is sought by collectors and professionals, thus making Paris, in mid-September of every year, the principal cultural destination on an international scale. Organized in conjunction with The 2017 Paris Biennial, there will be two major exhibitions initiated by the Marmottan Monet and the Jacquemart André Museums, the former presenting a first-of-its-kind exhibition on « Monet, Collector » and the second exhibiting a tribute to Impressionism With «The Impressionist Treasures of the Ordrupgaard Collection - Sisley, Cézanne, Monet, Renoir, Gauguin.» THE BIENNALE PARIS PRESS RELEASE — PARIS, MAY 15, 2017 3 THE PARIS BIENNIAL AND « CHANTILLY ARTS AND ELEGANCE: RICHARD MILLE » In this spirit, The 2017 Paris Biennial has initiated a partnership with « Chantilly Arts and Elegance Richard Mille » which will, on September 10, 2017, present the most world’s most beautiful historical and collectors’ cars, along with couturiers’ creations, automobile clubs and the French Art of Living, at the Domaine de Chantilly. -

Financial Panics and Scandals

Wintonbury Risk Management Investment Strategy Discussions www.wintonbury.com Financial Panics, Scandals and Failures And Major Events 1. 1343: the Peruzzi Bank of Florence fails after Edward III of England defaults. 2. 1621-1622: Ferdinand II of the Holy Roman Empire debases coinage during the Thirty Years War 3. 1634-1637: Tulip bulb bubble and crash in Holland 4. 1711-1720: South Sea Bubble 5. 1716-1720: Mississippi Bubble, John Law 6. 1754-1763: French & Indian War (European Seven Years War) 7. 1763: North Europe Panic after the Seven Years War 8. 1764: British Currency Act of 1764 9. 1765-1769: Post war depression, with farm and business foreclosures in the colonies 10. 1775-1783: Revolutionary War 11. 1785-1787: Post Revolutionary War Depression, Shays Rebellion over farm foreclosures. 12. Bank of the United States, 1791-1811, Alexander Hamilton 13. 1792: William Duer Panic in New York 14. 1794: Whiskey Rebellion in Western Pennsylvania (Gallatin mediates) 15. British currency crisis of 1797, suspension of gold payments 16. 1808: Napoleon Overthrows Spanish Monarchy; Shipping Marques 17. 1813: Danish State Default 18. 1813: Suffolk Banking System established in Boston and eventually all of New England to clear bank notes for members at par. 19. Second Bank of the United States, 1816-1836, Nicholas Biddle 20. Panic of 1819, Agricultural Prices, Bank Currency, and Western Lands 21. 1821: British restoration of gold payments 22. Republic of Poyais fraud, London & Paris, 1820-1826, Gregor MacGregor. 23. British Banking Crisis, 1825-1826, failed Latin American investments, etc., six London banks including Henry Thornton’s Bank and sixty country banks failed. -

Une Bibliographie Commentée En Temps Réel : L'art De La Performance

Une bibliographie commentée en temps réel : l’art de la performance au Québec et au Canada An Annotated Bibliography in Real Time : Performance Art in Quebec and Canada 2019 3e édition | 3rd Edition Barbara Clausen, Jade Boivin, Emmanuelle Choquette Éditions Artexte Dépôt légal, novembre 2019 Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec Bibliothèque et Archives du Canada. ISBN : 978-2-923045-36-8 i Résumé | Abstract 2017 I. UNE BIBLIOGraPHIE COMMENTÉE 351 Volet III 1.11– 15.12. 2017 I. AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGraPHY Lire la performance. Une exposition (1914-2019) de recherche et une série de discussions et de projections A B C D E F G H I Part III 1.11– 15.12. 2017 Reading Performance. A Research J K L M N O P Q R Exhibition and a Series of Discussions and Screenings S T U V W X Y Z Artexte, Montréal 321 Sites Web | Websites Geneviève Marcil 368 Des écrits sur la performance à la II. DOCUMENTATION 2015 | 2017 | 2019 performativité de l’écrit 369 From Writings on Performance to 2015 Writing as Performance Barbara Clausen. Emmanuelle Choquette 325 Discours en mouvement 370 Lieux et espaces de la recherche 328 Discourse in Motion 371 Research: Sites and Spaces 331 Volet I 30.4. – 20.6.2015 | Volet II 3.9 – Jade Boivin 24.10.201 372 La vidéo comme lieu Une bibliographie commentée en d’une mise en récit de soi temps réel : l’art de la performance au 374 Narrative of the Self in Video Art Québec et au Canada. Une exposition et une série de 2019 conférences Part I 30.4. -

The Unicode Standard, Version 6.3

Currency Symbols Range: 20A0–20CF This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 6.3 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See http://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See http://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See http://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-6.3/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 6.3. See http://www.unicode.org/Public/6.3.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 6.3. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 6.3 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 6.3, online at http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode6.3.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, and #45, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See http://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and http://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

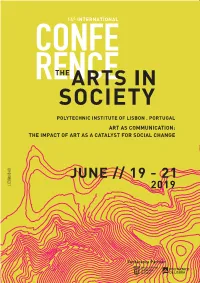

Art As Communication: Y the Impact of Art As a Catalyst for Social Change Cm

capa e contra capa.pdf 1 03/06/2019 10:57:34 POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE OF LISBON . PORTUGAL C M ART AS COMMUNICATION: Y THE IMPACT OF ART AS A CATALYST FOR SOCIAL CHANGE CM MY CY CMY K Fifteenth International Conference on The Arts in Society Against the Grain: Arts and the Crisis of Democracy NUI Galway Galway, Ireland 24–26 June 2020 Call for Papers We invite proposals for paper presentations, workshops/interactive sessions, posters/exhibits, colloquia, creative practice showcases, virtual posters, or virtual lightning talks. Returning Member Registration We are pleased to oer a Returning Member Registration Discount to delegates who have attended The Arts in Society Conference in the past. Returning research network members receive a discount o the full conference registration rate. ArtsInSociety.com/2020-Conference Conference Partner Fourteenth International Conference on The Arts in Society “Art as Communication: The Impact of Art as a Catalyst for Social Change” 19–21 June 2019 | Polytechnic Institute of Lisbon | Lisbon, Portugal www.artsinsociety.com www.facebook.com/ArtsInSociety @artsinsociety | #ICAIS19 Fourteenth International Conference on the Arts in Society www.artsinsociety.com First published in 2019 in Champaign, Illinois, USA by Common Ground Research Networks, NFP www.cgnetworks.org © 2019 Common Ground Research Networks All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the applicable copyright legislation, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. For permissions and other inquiries, please visit the CGScholar Knowledge Base (https://cgscholar.com/cg_support/en). -

North Dakota Mill Executive Session

Minutes of a Meeting of the Industrial Commission of North Dakota Held on October 22, 2020 beginning at 12:30 p.m. Ft. Union Room - State Capitol Present: Governor Doug Burgum, Chairman Attorney General Wayne Stenehjem Agriculture Commissioner Doug Goehring Also Present: Some attendees are listed on the attendance sheet available in the Commission files This meeting was open through a call-in number so not all attendees are known Members of the Press Governor Doug Burgum called the Industrial Commission meeting to order at approximately 12:30 p.m. and the Commission took up Mill business. NORTH DAKOTA MILL (“Mill”) It was moved by Attorney General Stenehjem and seconded by Commissioner Goehring that under the provisions of N.D.C.C. § 44-04-18.4 the Industrial Commission proceed into executive session to discuss commercial information including the North Dakota Mill’s marketing strategies and sales plans. On a roll call vote, Governor Burgum, Attorney General Stenehjem, and Commissioner Goehring voted aye. The motion carried unanimously. Governor Burgum noted that the executive session would be recorded. He reminded the Commission members and those present to limit their discussion to the announced topic during the executive session, which was anticipated to last 15 minutes. It was noted that upon conclusion of the executive session the Commission would reconvene in open session. Commission members, their staff, and employees of the North Dakota Mill were instructed to participate using the directions they had been given. The executive session began at 12:35 p.m. NORTH DAKOTA MILL EXECUTIVE SESSION Members Present: Governor Doug Burgum Attorney General Wayne Stenehjem Commissioner Doug Goehring Others in Attendance: Leslie Bakken Oliver Governor’s Office Reice Haase Governor’s Office John Schneider Department of Agriculture Vance Taylor State Mill (Phone) Cathy Dub State Mill (Phone) Karlene Fine Industrial Commission Office Andrea Pfennig Industrial Commission Office The North Dakota Mill executive session ended at 1:01 p.m.