Introduction Langland As an Early Modern Author 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religious Forms and Institutions in Piers Plowman

This essay appeared in The Cambridge Companion to Piers Plowman, edited by Andrew Cole and Andy Galloway (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 97-116 Religious Forms and Institutions in Piers Plowman James Simpson KEY WORDS: William Langland, Piers Plowman, selfhood and institutions; late medieval religious institutions ABSTRACT Which comes first: institutions or selves? Liberal democracies operate as if selves preceded institutions. By and large, pre-Reformation culture places the institution before the self. The self, and particularly the conscience as the source of deepest ethical and spiritual counsel, is intimately shaped, by the institution of the Church. This shaping is both ethical and spiritual; by no means least, it ensures the soul’s salvation, though administering the sacraments especially of baptism, penance, and the Eucharist. The conscience is not a lonely entity in such an institutional culture. It is, rather, the portable voice of accumulated, communal history and wisdom: it is, as the word itself suggests, a ‘con-scientia’, a ‘knowing with’. These tensions generate the extraordinary and conflicted account of self and institution in Langland’s Piers Plowman. 1 Religious Forms and Institutions in Piers Plowman Which comes first: institutions or selves? Liberal democracies operate as if selves preceded institutions, since electors choose their institutional representatives, who themselves vote to shape institutions. Liberal ideology, indeed, traces its genealogy back to heroic moments of the lonely, fully-formed conscience standing up against the might of institutions; those heroes (Luther is the most obvious example) are lionized precisely because they are said to have established the grounds of choice: every individual will be able to choose, in freedom, his or her institutional affiliation for him or herself. -

DISSERTATION-Submission Reformatted

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5tv2w736 Author Harkins, Robert Lee Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 By Robert Lee Harkins A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan Professor David Bates Fall 2013 © Robert Lee Harkins 2013 All Rights Reserved 1 Abstract The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 by Robert Lee Harkins Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair This study examines the problem of religious and political obedience in early modern England. Drawing upon extensive manuscript research, it focuses on the reign of Mary I (1553-1558), when the official return to Roman Catholicism was accompanied by the prosecution of Protestants for heresy, and the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603), when the state religion again shifted to Protestantism. I argue that the cognitive dissonance created by these seesaw changes of official doctrine necessitated a society in which religious mutability became standard operating procedure. For most early modern men and women it was impossible to navigate between the competing and contradictory dictates of Tudor religion and politics without conforming, dissimulating, or changing important points of conscience and belief. -

2 the Seven Deadly Sins</Em>

Early Theatre 10.1 (2007) ROBERT HORNBACK The Reasons of Misrule Revisited: Evangelical Appropriations of Carnival in Tudor Revels Undoubtedly the most arresting Tudor likeness in the National Portrait Gallery, London, is William Scrots’s anamorphosis (NPG1299). As if mod- eled after a funhouse mirror reflection, this colorful oil on panel painting depicts within a stretched oblong, framed within a thin horizontal rectangle, the profile of a child with red hair and a head far wider than it is tall; measur- ing 63 inches x 16 ¾ inches, the portrait itself is, the Gallery website reports, its ‘squattest’ (‘nearly 4 times wider than it is high’). Its short-lived sitter’s nose juts out, Pinocchio-like, under a low bump of overhanging brow, as the chin recedes cartoonishly under a marked overbite. The subject thus seems to prefigure the whimsical grotesques of Inigo Jones’s antimasques decades later rather than to depict, as it does, the heir apparent of Henry VIII. Such is underrated Flemish master Scrots’s tour de force portrait of a nine-year-old Prince Edward in 1546, a year before his accession. As the NPG website ex- plains, ‘[Edward] is shown in distorted perspective (anamorphosis) …. When viewed from the right,’ however, ie, from a small cut-out in that side of the frame, he can be ‘seen in correct perspective’.1 I want to suggest that this de- lightful anamorphic image, coupled with the Gallery’s dry commentary, pro- vides an ironic but apt metaphor for the critical tradition addressing Edward’s reign and its theatrical spectacle: only when viewed from a one-sided point of view – in hindsight, from the anachronistic vantage point of an Anglo-Amer- ican tradition inflected by subsequent protestantism – can the boy king, his often riotous court spectacle, and mid-Tudor evangelicals in general be made to resemble a ‘correct’ portrait of the protestant sobriety, indeed the dour puritanism, of later generations. -

DISSERTATION-Submission Reformatted

The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 By Robert Lee Harkins A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan Professor David Bates Fall 2013 © Robert Lee Harkins 2013 All Rights Reserved 1 Abstract The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 by Robert Lee Harkins Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair This study examines the problem of religious and political obedience in early modern England. Drawing upon extensive manuscript research, it focuses on the reign of Mary I (1553-1558), when the official return to Roman Catholicism was accompanied by the prosecution of Protestants for heresy, and the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603), when the state religion again shifted to Protestantism. I argue that the cognitive dissonance created by these seesaw changes of official doctrine necessitated a society in which religious mutability became standard operating procedure. For most early modern men and women it was impossible to navigate between the competing and contradictory dictates of Tudor religion and politics without conforming, dissimulating, or changing important points of conscience and belief. Although early modern theologians and polemicists widely declared religious conformists to be shameless apostates, when we examine specific cases in context it becomes apparent that most individuals found ways to positively rationalize and justify their respective actions. This fraught history continued to have long-term effects on England’s religious, political, and intellectual culture. -

John Bale's <I>Kynge Johan</I> As English Nationalist Propaganda

Quidditas Volume 35 Article 10 2014 John Bale’s Kynge Johan as English Nationalist Propaganda G. D. George Prince George's County Public Schools, Prince George's Community College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Renaissance Studies Commons Recommended Citation George, G. D. (2014) "John Bale’s Kynge Johan as English Nationalist Propaganda," Quidditas: Vol. 35 , Article 10. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol35/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quidditas by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Quidditas 35 (2014) 177 John Bale’s Kynge Johan as English Nationalist Propaganda G. D. George Prince George’s County Public Schools Prince George’s Community College John Bale is generally associated with the English Reformation rather than the Tudor government. It may be that Bale’s well-know protestant polemics tend to overshadow his place in Thomas Cromwell’s propaganda machine, and that Bale’s Kynge Johan is more a propaganda piece for the Tudor monarchy than it is just another of his Protestant dramas.. Introduction On 2 January, 1539, a “petie and nawghtely don enterlude,” that “put down the Pope and Saincte Thomas” was presented at Canterbury.1 Beyond the fact that a four hundred sixty-one year old play from Tudor England remains extant in any form, this particular “enterlude,” John Bale’s play Kynge Johan,2 remains of particular interest to scholars for some see Johan as meriting “a particular place in the history of the theatre. -

Easter 2016 Tel: 01394 270187

BETHESDA BAPTIST CHURCH, CAVENDISH ROAD, FELIXSTOWE, IP11 2AR EASTER 2016 TEL: 01394 270187. WEB: bethesdafelixstowe.com frustration, all show us that things are not right with the world – or with us. What hope is there? WHAT IS LIFE? The end pages of the Bible promise “a new heaven and a new earth”, a “holy city” shining with the glory of God, where “God will dwell with his people Have you ever asked … ? and be their God; He will wipe every tear from their eyes; there will be no more death or mourning or What can I get out of life? Isn’t there more to life crying or pain.” (Revelation ch 21 v 3). Nothing than this? What’s the point of it all? Why am I which could ruin it will ever enter it. (verse 27) here? What happens at the end of it all? How will this be possible, when “We all, like sheep, Some of you may know the little Suffolk village of have gone astray, each of us has turned to his own Dunwich, about 30 miles up the coast from way”? Because, at the cross (which we remember at Felixstowe. But did you know that it was once a Easter), “The Lord has laid on Him [Jesus] the thriving port and one of the ten most important iniquity of us all.” (Isaiah 53:6). “Iniquity” means cities in England? Sadly, all that’s left above water our disobedience against God. Jesus suffered in our now is a tiny village steadily falling into the sea. place, so that He could promise, “I tell you the truth, Like Dunwich, we – mankind, all of us – have fallen he who believes has everlasting life.” (John 6:47) from splendour to ruin. -

Editorial. Sports Geography : an Overview

Belgeo Revue belge de géographie 2 | 2008 Sports geography Editorial. Sports Geography : an overview John Bale and Trudo Dejonghe Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/belgeo/10253 DOI: 10.4000/belgeo.10253 ISSN: 2294-9135 Publisher: National Committee of Geography of Belgium, Société Royale Belge de Géographie Printed version Date of publication: 30 June 2008 Number of pages: 157-166 ISSN: 1377-2368 Electronic reference John Bale and Trudo Dejonghe, “Editorial. Sports Geography : an overview”, Belgeo [Online], 2 | 2008, Online since 20 October 2013, connection on 21 September 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/belgeo/10253 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/belgeo.10253 This text was automatically generated on 21 September 2021. Belgeo est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International. Editorial. Sports Geography : an overview 1 Editorial. Sports Geography : an overview John Bale and Trudo Dejonghe 1 Geographical studies of sports are not new. The first time that sport was mentioned in a geographical publication was in 1879 when Elisée Réclus said something about cricket in his Géographie Universelle. In 1919 Hilderbrand published in the National Geographic Magazine The Geography of Games. A few years later in 1927, the German geographer Hettner (quoted in Elkins, 1989) suggested that among other things, the variations in health, hygiene, recreation and education could be “apprehended as manifestations of the nature of the land”. This comment by Hettner, and earlier work by the American geographers Huntington and Semple, could also be included among environmental determinists for whom body-cultural practices were seen as perfectly legitimate fields of study (Bale, 2002). -

Style: Figuring Subjectivity in 'Piers Plowman C' and 'The Parson's Tale' and 'Retraction': Authorial Insertion and Identity Poetics 04/05/2006 09:03 AM

Style: Figuring subjectivity in 'Piers Plowman C' and 'The Parson's Tale' and 'Retraction': authorial insertion and identity poetics 04/05/2006 09:03 AM FindArticles > Style > Fall, 1997 > Article > Print friendly Figuring subjectivity in 'Piers Plowman C' and 'The Parson's Tale' and 'Retraction': authorial insertion and identity poetics Daniel F. Pigg For some time, scholars and readers of Chaucer have pondered his knowledge about one of the major poets of his day: William Langland. Readers may typically find statements in scholarly discourse such as "We can now scarcely avoid considering the probability of Chaucer's having actually seen a copy of Piers Plowman in the interval between its first publication (c. 1370) and the beginnings of the Tales at least ten years later" (Bennett 321). Given internal evidence in the fifth passus of the C text - if we are willing to accept any connection between Langland's "autobiographical" confession/apologia and the writer - and documentary evidence of the historical Chaucer, we must assume that each poet was in London for at least a short time. Hypotheses about Chaucer's reading have always been at the forefront of scholarly debate. No one, however, has been about to demonstrate absolutely that Chaucer had knowledge of Piers Plowman. In her closing remarks at the 1994 New Chaucer Society meeting in Dublin, Ireland, Anne Middleton challenged those present to "trouble Chaucer's silences." The present attempt to "trouble the silence" relates to the growth and development of major poetic projects: the C text of Piers Plowman (likely written in the 1380s) and the "final" shape of the Canterbury Tales. -

Thomas Churchyard: a Study of His Prose and Poetry

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 67-6366 ST. ONGE, Henry Orion, 1927- THOMAS CHURCHYARD: A STUDY OF HIS PROSE AND POETRY. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1966 Language and Literature, general University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan © Copyright by Henry Orion St. Onge 1967 THOMAS CHURCHYARD: A STUDY OF HIS PROSE AND POETRY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Henry Orion St. Onge, A.E., M.A. ******* The Ohio State University 1966 Approved by Adviser Department of English ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Although it is perhaps in the natural order of things that a doctoral candidate acknowledges the aid and guidance of his adviser, in my case I feel that the circumstances are somewhat out of the ordinary. Therefore, I wish to make a special acknowledgment of the great debt I owe to my adviser. Professor Ruth W. Hughey. The debt is due not only to her expenditure of scholarship but is owed as well to the demands I have made on her kindness and generosity and patience. I would like also to acknowledge the understanding treatment I received from the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of The Ohio State University. It goes without saying that I thank the professors of the English Department of The Ohio State University who have taught me and encouraged me. Finally, I must express my gratitude to the staffs of - the libraries at The Ohio State University, Cornell Univer sity, St. Lawrence University, and the State University of New York. -

The Account Book of a Marian Bookseller, 1553-4

THE ACCOUNT BOOK OF A MARIAN BOOKSELLER, 1553-4 JOHN N. KING MS. EGERTON 2974, fois. 67-8, preserves in fragmentary form accounts from the day-book of a London stationer who was active during the brief interval between the death on 6 July 1553 of Edward VI, whose regents allowed unprecedented liberty to Protestant authors, printers, publishers, and booksellers, and the reimposition of statutory restraints on publication by the government of Queen Mary. The entries for dates, titles, quantities, paper, and prices make it clear that the leaves come from a bookseller's ledger book. Their record of the articles sold each day at the stationer's shop provides a unique view of the London book trade at an unusually turbulent point in the history of English publishing. Before they came into the holdings of the British Museum, the two paper leaves (fig. i) were removed from a copy of William Alley's The poore mans librarie (1565) that belonged to Thomas Sharpe of Coventry. They are described as having been pasted at the end ofthe volume *as a fly leaf, and after their removal, William Hamper enclosed them as a gift in a letter of 17 March 1810 to the Revd Thomas Frognall Dibdin (MS. Egerton 2974, fois. 62, 64). The leaves are unevenly trimmed, but each measures approximately 376 x 145 mm overall. Because of their format they are now bound separately, but they formed part of a group of letters to Dibdin purchased loose and later bound in the Museum, so they belong together with MS. -

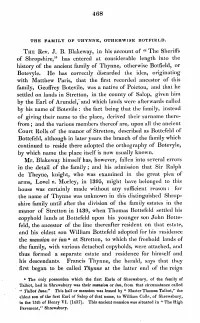

The Sheriffs of Shropshire," Has Entered at Considerable Length Into the History of the Ancient Family of Thynne, Otherwise Botfield, Or Botevyle

468 THE FAMILY OF 'l'HYNNE, OTHERWISE BO'l'FIELD. THE Rev. J. B. Blakeway, in his account of "The Sheriffs of Shropshire," has entered at considerable length into the history of the ancient family of Thynne, otherwise Botfield, or Botevyle. He has correctly discarded the idea, originating with Matthew Paris, that the first recorded ancestor of this family, Geoffrey Botevile, was a native of Poictou, and that he settled on lands in Stretton, in the county of Salop, given him by the Earl of Arundel,' .and which lands were afterwards called by his name of Botevile: the fact being that the family, instead of giving their name to the place, derived their surname there• from; and the various members thereof are, upon all the ancient Court Rolls of the manor of Stretton, described as Bottefeld of Bottefeld, although in later years the branch of the family which continued to reside there adopted the orthography of Botevyle, by which name the place itself is now usually known. Mr. Blakeway himself has, however, fallen into several errors in the detail of the family; and his admission that Sir Ralph de Theyne, knight, who was examined in the great plea of arms, Lovel v. Morley, in 1395, might have belonged to this house was certainly made without any sufficient reason : for the name of Thynne was unknown in this distinguished Shrop• shire family until after the division of the family estates in the manor of Stretton in 1439, when Thomas Bottefeld settled his copyhold lands at Bottefeld upon his younger son John Botte• feld, the ancestor of the line thereafter resident on that estate, and his eldest son William Bottefeld adopted for his residence the mansion or inn a at Stretton, to which the freehold lands of the family, with various detached copyholds, were attached, and thus formed a separate estate and residence for himself and his descendants. -

Packaging Thomas Speght's Chaucer for Renaissance Readers

Article “In his old dress”: Packaging Thomas Speght's Chaucer for Renaissance Readers SINGH, Devani Mandira Abstract This article subjects Thomas Speght's Chaucer editions (1598; 1602) to a consideration of how these books conceive, invite, and influence their readership. Studying the highly wrought forms of the dedicatory epistle to Sir Robert Cecil, the prefatory letter by Francis Beaumont, and the address “To the Readers,” it argues that these paratexts warrant closer attention for their treatment of the entangled relationships between editor, patron, and reader. Where prior work has suggested that Speght’s audience for the editions was a socially horizontal group and that he only haltingly sought wider publication, this article suggests that the preliminaries perform a multivocal role, poised to readily receive a diffuse readership of both familiar and newer consumers. Reference SINGH, Devani Mandira. “In his old dress”: Packaging Thomas Speght’s Chaucer for Renaissance Readers. Chaucer Review, 2016, vol. 51, no. 4, p. 478-502 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:88361 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 Pre-copyedited version of the article published in The Chaucer Review 51.4 (2016): 478-502. “In his old dress”: Packaging Thomas Speght’s Chaucer for Renaissance Readers Devani Singh Abstract: This article subjects Thomas Speght's Chaucer editions (1598; 1602) to a consideration of how these books conceive, invite, and influence their readership. Studying the highly wrought forms of the dedicatory epistle to Sir Robert Cecil, the prefatory letter by Francis Beaumont, and the address “To the Readers,” it argues that these paratexts warrant closer attention for their treatment of the entangled relationships between editor, patron, and reader.