Evil in Urban Fantasy Literature Cassandra Ashton a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mythlore Index Plus

MYTHLORE INDEX PLUS MYTHLORE ISSUES 1–137 with Tolkien Journal Mythcon Conference Proceedings Mythopoeic Press Publications Compiled by Janet Brennan Croft and Edith Crowe 2020. This work, exclusive of the illustrations, is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA. Tim Kirk’s illustrations are reproduced from early issues of Mythlore with his kind permission. Sarah Beach’s illustrations are reproduced from early issues of Mythlore with her kind permission. Copyright Sarah L. Beach 2007. MYTHLORE INDEX PLUS An Index to Selected Publications of The Mythopoeic Society MYTHLORE, ISSUES 1–137 TOLKIEN JOURNAL, ISSUES 1–18 MYTHOPOEIC PRESS PUBLICATIONS AND MYTHCON CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS COMPILED BY JANET BRENNAN CROFT AND EDITH CROWE Mythlore, January 1969 through Fall/Winter 2020, Issues 1–137, Volume 1.1 through 39.1 Tolkien Journal, Spring 1965 through 1976, Issues 1–18, Volume 1.1 through 5.4 Chad Walsh Reviews C.S. Lewis, The Masques of Amen House, Sayers on Holmes, The Pedant and the Shuffly, Tolkien on Film, The Travelling Rug, Past Watchful Dragons, The Intersection of Fantasy and Native America, Perilous and Fair, and Baptism of Fire Narnia Conference; Mythcon I, II, III, XVI, XXIII, and XXIX Table of Contents INTRODUCTION Janet Brennan Croft .....................................................................................................................................1 -

Utah for 2019 Nasfic

Warren Buff Site Selection Administrator, Worldcon 76 NASFiC 2019 voting @ Worldcon 76, San Jose, California, 12/18/2017 Dear Mr. Buff, Please find attached the documents announcing the Utah Fandom Organization’s bid to hold NASFiC in Layton, Utah on July 4th - 7th, 2019. This is our formal request under Article 4 of the WSFS constitution. Our proposed facility is the Davis Conference Center with the attached Hilton Garden Inn, as well as courtesy room blocks in overflow hotels provided through our Davis County Tourism & Events Board; documents also attached. Please note Layton, Utah is more than 500 miles from San Jose, California, to fulfill the mileage radius required by the constitution. You can find our extra details and enthusiasm at http://www.utahfor2019.com . I have also attached a full list of our Bid Team, as well as our Westercon 72 committee who jumps in to help all across the globe. Attached includes our UFO bylaws and articles of incorporation. If selected, we will operate as part of the standing committee established by UFO to operate Westercon 72. The Chair of the committee is selected by the President of the corporation and ratified by the Board of Directors. The Chair can be removed by a vote of an majority of the entire membership of the Board of Directors. Thank you for your consideration. We hope to do the Worldcon & NASFiC fan community proud. Kate Hatcher President of U.F.O Chair of Westercon 72 & Co Bid Chair of NASFiC 2019 [email protected] [email protected] Utahfor2019.com 12/18/17 NASFiC Bid -

Reading List

Springwood Yr7; for the love of reading… Please find below a list of suggestions from many of our subjects on what you could read to improve your knowledge and understanding. If you find something better please tell Mr Scoles and I will update this page! In History we recommend students read the Horrible History series of books as these provide a fun and factual insight into many of the time periods they will study at Springwood. Further reading of novels like War Horse by Michael Morpurgo or the stories of King Arthur by local author Kevin Crossley-Holland are well worth a read. Geography recommends the Horrible Geography books as they are well written and popular with our current students, plus any travel guides you can find in local libraries. Learning a foreign language presents its own challenges when producing a reading list, but students can still do a lot for themselves to improve; Duolingo is a free language learning app, a basic phrasebooks with CD and websites like www.languagesonline.org.uk and Linguascope (please ask your German teacher for a username and password) are very helpful. Students can also subscribe to Mary Glasgow MFL reading magazines (in French, German or Spanish), these are full of fun quizzes and articles. www.maryglasgowplus.com/order_forms/1 Please look for the beginner magazines; Das Rad, Allons-y! or Que Tal? Websites are also useful for practical subjects like Food www.foodafactoflife.org or Design and Technology, www.technologystudent.com. Science recommend the Key Stage 3 revision guide that you can purchase from our school shop plus the following websites; http://www.bbc.co.uk/learningzone/clips/topics/secondary.shtml#science http://www.s-cool.co.uk/gcse http://www.science-active.co.uk/ http://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/ks3/ English as you would expect have a wide selection of titles that they have sent to all students via Show My Homework. -

THE 2016 DELL MAGAZINES AWARD This Year’S Trip to the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Was Spent in a Whirl of Activity

EDITORIAL Sheila Williams THE 2016 DELL MAGAZINES AWARD This year’s trip to the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts was spent in a whirl of activity. In addition to academic papers, author readings, banquets, and the awards ceremony, it was a celebration of major life events. Thursday night saw a surprise birthday party for well-known SF and fantasy critic Gary K. Wolfe and a compelling memorial for storied editor David G. Hartwell. Sunday morning brought us the beautiful wedding of Rebecca McNulty and Bernie Goodman. Rebecca met Bernie when she was a finalist for our annual Dell Magazines Award for Undergraduate Ex- cellence in Science Fiction and Fantasy Writing several years ago. Other past finalists were also in attendance at the conference. In addition to Re- becca, it was a joy to watch E. Lily Yu, Lara Donnelly, Rich Larson, and Seth Dickin- son welcome a brand new crop of young writers. The winner of this year’s award was Rani Banjarian, a senior at Vanderbilt University. Rani studied at an international school in Beirut, Lebanon, before coming to the U.S. to attend college. Fluent in Arabic and English, he’s also toying with adding French to his toolbox. Rani is graduating with a duel major in physics and writing. His award winning short story, “Lullabies in Arabic” incorporates his fascination with memoir writing along with a newfound interest in science fiction. My co-judge Rick Wilber and I were once again pleased that the International Association for the Fantastic in the Arts and Dell Magazines cosponsored Rani’s expense-paid trip to the conference in Orlando, Florida, and the five hundred dollar prize. -

Congratulations Susan & Joost Ueffing!

CONGRATULATIONS SUSAN & JOOST UEFFING! The Staff of the CQ would like to congratulate Jaguar CO Susan and STARFLEET Chief of Operations Joost Ueffi ng on their September wedding! 1 2 5 The beautiful ceremony was performed OCT/NOV in Kingsport, Tennessee on September 2004 18th, with many of the couple’s “extended Fleet family” in attendance! Left: The smiling faces of all the STARFLEET members celebrating the Fugate-Ueffi ng wedding. Photo submitted by Wade Olsen. Additional photos on back cover. R4 SUMMIT LIVES IT UP IN LAS VEGAS! Right: Saturday evening banquet highlight — commissioning the USS Gallant NCC 4890. (l-r): Jerry Tien (Chief, STARFLEET Shuttle Ops), Ed Nowlin (R4 RC), Chrissy Killian (Vice Chief, Fleet Ops), Larry Barnes (Gallant CO) and Joe Martin (Gallant XO). Photo submitted by Wendy Fillmore. - Story on p. 3 WHAT IS THE “RODDENBERRY EFFECT”? “Gene Roddenberry’s dream affects different people in different ways, and inspires different thoughts... that’s the Roddenberry Effect, and Eugene Roddenberry, Jr., Gene’s son and co-founder of Roddenberry Productions, wants to capture his father’s spirit — and how it has touched fans around the world — in a book of photographs.” - For more info, read Mark H. Anbinder’s VCS report on p. 7 USPS 017-671 125 125 Table Of Contents............................2 STARFLEET Communiqué After Action Report: R4 Conference..3 Volume I, No. 125 Spies By Night: a SF Novel.............4 A Letter to the Fleet........................4 Published by: Borg Assimilator Media Day..............5 STARFLEET, The International Mystic Realms Fantasy Festival.......6 Star Trek Fan Association, Inc. -

Award Winning Books (508) 531-1304

EDUCATIONAL RESOURCE CENTER Clement C. Maxwell Library 10 Shaw Road Bridgewater MA 02324 AWARD WINNING BOOKS (508) 531-1304 http://www.bridgew.edu/library/ Revised: May 2013 cml Table of Contents Caldecott Medal Winners………………………. 1 Newbery Medal Winners……………………….. 5 Coretta Scott King Award Winners…………. 9 Mildred Batchelder Award Winners……….. 11 Phoenix Award Winners………………………… 13 Theodor Seuss Geisel Award Winners…….. 14 CALDECOTT MEDAL WINNERS The Caldecott Medal was established in 1938 and named in honor of nineteenth-century English illustrator Randolph Caldecott. It is awarded annually to the illustrator of the most distinguished American picture book for children published in the previous year. Location Call # Award Year Pic K634t This is Not My Hat. John Klassen. (Candlewick Press) Grades K-2. A little fish thinks he 2013 can get away with stealing a hat. Pic R223b A Ball for Daisy. Chris Raschka. (Random House Children’s Books) Grades preschool-2. A 2012 gray and white puppy and her red ball are constant companions until a poodle inadvertently deflates the toy. Pic S7992s A Sick Day for Amos McGee. Philip C. Stead. (Roaring Brook Press) Grades preschool-1. 2011 The best sick day ever and the animals in the zoo feature in this striking picture book. Pic P655l The Lion and the Mouse. Jerry Pinkney. (Little, Brown and Company) Grades preschool- 2010 1. A wordless retelling of the Aesop fable set in the African Serengeti. Pic S9728h The House in the Night. Susan Marie Swanson. (Houghton Mifflin) Grades preschool-1. 2009 Illustrations and easy text explore what makes a house in the night a home filled with light. -

Reflections of the Bible in Shakespeare's Richard Iii

REFLECTIONS OF THE BIBLE IN SHAKESPEARE'S RICHARD III By. FLEUR.FULLER Bachelor of Arts Texas Technological College Lubbock, Texas 1960 Submitted to the faculty of the Graduate School of the. Oklahoma Stat.e University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August~ 1962 OKLAHOMA STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY NOV 8 1962 REFLECTIONS OF THE BIBLE IN SHAKESPEARE'S RICHARD III Thesis Approved: :V«Nid sThesis. B~J~ Adviser lJ(My:.a R~ 7i5eanorthe Graduate School 504442 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to Dro David So Berkeley for the idea which led to this study and for numerous contributions ·while the investigation was being made. I am also indebted to Dr" Daniel Kroll for several valuable suggestions, to Mro Joe Fo Watson for help in Biblical interpretation, and to Miss Helen Donart for assistance in procuring books through inter-library loano iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 Chapters: I. THEME 6 0 oll• • 411 • II IJ Ill e • ti O 11 II< Ii' • lJ, 'Ill II Ill Ill lb Iii • Ill • 0 .. Ill ljl 11' dt ,0, Ill O • (J• Ill O I! fl, 0 «. di• ,ft 6 II. CHARACTERIZATION 28 III. PLOTTING Ill O 41 0 Ill 11> Ill ,a, II II II fl, 'II- fl O II ti' II It 'II fl Cl> Ill .. 0 $ t, ell 41• • II fl O ,q, fl to Cl II ill Ill (t Cl II II 59 CONCLUSION 73 NOTES 76 BIBLIOGRAPHY 82 iv INTRODUCTION That Shak:espeare' s i,mrks are saturated with Biblical allusions is indisputableo Even the most casual reader of Shakespeare cannot fail to recognize many direct Scrip- tural references, and, through the years, Shakespearean scholars -

Arch : Northwestern University Institutional Repository

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Myth and the Modern Problem: Mythic Thinking in Twentieth-Century Britain A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of History By Matthew Kane Sterenberg EVANSTON, ILLINOIS December 2007 2 © Copyright by Matthew Kane Sterenberg 2007 All Rights Reserved 3 ABSTRACT Myth and the Modern Problem: Mythic Thinking in Twentieth-Century Britain Matthew Sterenberg This dissertation, “Myth and the Modern Problem: Mythic Thinking in Twentieth- Century Britain,” argues that a widespread phenomenon best described as “mythic thinking” emerged in the early twentieth century as way for a variety of thinkers and key cultural groups to frame and articulate their anxieties about, and their responses to, modernity. As such, can be understood in part as a response to what W.H. Auden described as “the modern problem”: a vacuum of meaning caused by the absence of inherited presuppositions and metanarratives that imposed coherence on the flow of experience. At the same time, the dissertation contends that— paradoxically—mythic thinkers’ response to, and critique of, modernity was itself a modern project insofar as it took place within, and depended upon, fundamental institutions, features, and tenets of modernity. Mythic thinking was defined by the belief that myths—timeless rather than time-bound explanatory narratives dealing with ultimate questions—were indispensable frameworks for interpreting experience, and essential tools for coping with and criticizing modernity. Throughout the period 1900 to 1980, it took the form of works of literature, art, philosophy, and theology designed to show that ancient myths had revelatory power for modern life, and that modernity sometimes required creation of new mythic narratives. -

Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: a Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Summer 8-7-2012 Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant James H. Shimkus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Shimkus, James H., "Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/95 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING SPECULATIVE FICTION IN COLLEGE: A PEDAGOGY FOR MAKING ENGLISH STUDIES RELEVANT by JAMES HAMMOND SHIMKUS Under the Direction of Dr. Elizabeth Burmester ABSTRACT Speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, and horror) has steadily gained popularity both in culture and as a subject for study in college. While many helpful resources on teaching a particular genre or teaching particular texts within a genre exist, college teachers who have not previously taught science fiction, fantasy, or horror will benefit from a broader pedagogical overview of speculative fiction, and that is what this resource provides. Teachers who have previously taught speculative fiction may also benefit from the selection of alternative texts presented here. This resource includes an argument for the consideration of more speculative fiction in college English classes, whether in composition, literature, or creative writing, as well as overviews of the main theoretical discussions and definitions of each genre. -

FANTASY SUPER LEAD Brandon Sanderson

TOR FANTASY JANUARY 2017 FANTASY SUPER LEAD Brandon Sanderson The Bands of Mourning #1 New York Times bestselling author continues the saga of Mistborn With The Alloy of Law and Shadows of Self, Brandon Sanderson surprised readers with a New York Times bestselling spinoff of his Mistborn books, set after the action of the trilogy, in a period corresponding to late 19th-century America. Now, with The Bands of Mourning, Sanderson continues the story. The Bands of Mourning are the mythical metalminds owned by the Lord Ruler, said to grant anyone who wears them the powers that the Lord Ruler had at his command. Hardly anyone thinks they really exist. A kandra researcher has returned to Elendel with images that seem to depict the Bands, as well as writings in a language that no one can read. Waxillium Ladrian is recruited ON-SALE DATE: 1/3/2017 to travel south to the city of New Seran to investigate. Along the way he ISBN-13: 9780765378583 discovers hints that point to the true goals of his uncle Edwarn and the EBOOK ISBN: 9781466862678 shadowy organization known as The Set. PRICE: $8.99 / $12.99 CAN. PAGES: 536 KEY SELLING POINTS: SPINE: 1.281 IN * LATEST INSTALLMENT OF THE MISTBORN SERIES: The Bands of CTN COUNT: 24 Mourning is the sequel to Shadows of Self and part of the Mistborn series, CPDA/CAT: 32/FANTASY but can be read as a stand-alone ORIGIN: TOR HC (1/16, * SANDERSON IS AN SF/F ROCK STAR: Sanderson is one of fantasy's 978-0-7653-7857-6) biggest stars and a constant fixture on the New York Times bestseller list, with a rapidly growing audience and dedicated fanbase AUTHOR HOME: UTAH For the Mistborn series and Brandon Sanderson MARKETING * Digital outreach through Twitter, Facebook, and the "Sanderson is an evil genius. -

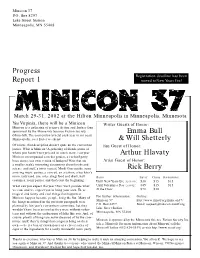

Progress Report 1 Emma Bull & Will Shetterly Arthur Hlavaty Rick

Minicon 37 P.O. Box 8297 Lake Street Station Minneapolis, MN 55408 Progress Re g i s t r ation deadline has been Report 1 mo ved toNew Years Eve! M a rch 29-31, 2002 at the Hilton Minneapolis in Minneapolis, Minnesota Yes Virginia, there will be a Minicon Writer Guests of Honor: Minicon is a gathering of science fiction and fantasy fans sponsored by the Minnesota Science Fiction Society Emma Bull (Minn-StF). The convention is held each year in (or near) Minneapolis, over Easter weekend. &Will Shetterly Of course, that description doesn't quite do the conven t i o n Fan Guest of Honor: justice. What is Minicon? A gathering of friends (some of whom you haven't met yet) and so much more. Last yea r Arthur Hlavaty Minicon encompassed a rocket garden, a cocktail party, bozo noses, our own version of Ju n k yard War s (but on Artist Guest of Honor: a smaller scale), interesting discussions about books and science and stuff, a trivia contest, Mardi Gras masks, some Rick Berry amazing music parties, a concert, an art show, a hucks t e r ' s room, tasty (and, um, interesting) food and drink, hall RATES: ADULT CHILD SUPPORTING costumes, room parties, and that's just the beginning. Until New Years Eve (1 2 / 3 1 / 0 1 ) : $3 0 $1 5 $1 5 What can you expect this year? Fun: we'll provide wha t Until Valentines Day (2 / 1 4 / 0 2 ) : $4 5 $1 5 $1 5 we can, and we expect you to bring your own. -

Troll's Eye View

Troll’s Eye View A Book of Villainous Tales Edited by Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling Available only from Teacher’s Junior Library Guild 7858 Industrial Parkway Edition Plain City, OH 43064 www.juniorlibraryguild.com Copyright © 2009 Junior Library Guild/Media Source, Inc. 0 About JLG Guides Junior Library Guild selects the best new hardcover children’s and YA books being published in the U.S. and makes them available to libraries and schools, often before the books are available from anyone else. Timeliness and value mark the mission of JLG: to be the librarian’s partner. But how can JLG help librarians be partners with classroom teachers? With JLG Guides. JLG Guides are activity and reading guides written by people with experience in both children’s and educational publishing—in fact, many of them are former librarians or teachers. The JLG Guides are made up of activity guides for younger readers (grades K–3) and reading guides for older readers (grades 4–12), with some overlap occurring in grades 3 and 4. All guides are written with national and state standards as guidelines. Activity guides focus on providing activities that support specific reading standards; reading guides support various standards (reading, language arts, social studies, science, etc.), depending on the genre and topic of the book itself. JLG Guides can be used both for whole class instruction and for individual students. Pages are reproducible for classroom use only, and a teacher’s edition accompanies most JLG Guides. Research indicates that using authentic literature in the classroom helps improve students’ interest level and reading skills.