2004 CREMP Executive Summary, May 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Dry Tortugas National Park

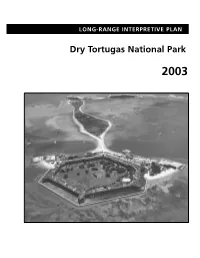

LONG-RANGE INTERPRETIVE PLAN Dry Tortugas National Park 2003 Cover Photograph: Aerial view of Fort Jefferson on Garden Key (fore- ground) and Bush Key (background). COMPREHENSIVE INTERPRETIVE PLAN Dry Tortugas National Park 2003 LONG-RANGE INTERPRETIVE PLAN Dry Tortugas National Park 2003 Prepared by: Department of Interpretive Planning Harpers Ferry Design Center and the Interpretive Staff of Dry Tortugas National Park and Everglades National Park INTRODUCTION About 70 miles west of Key West, Florida, lies a string of seven islands called the Dry Tortugas. These sand and coral reef islands, or keys, along with 100 square miles of shallow waters and shoals that surround them, make up Dry Tortugas National Park. Here, clear views of water and sky extend to the horizon, broken only by an occasional island. Below and above the horizon line are natural and historical treasures that continue to beckon and amaze those visitors who venture here. Warm, clear, shallow, and well-lit waters around these tropical islands provide ideal conditions for coral reefs. Tiny, primitive animals called polyps live in colonies under these waters and form skeletons from cal- cium carbonate which, over centuries, create coral reefs. These reef ecosystems support a wealth of marine life such as sea anemones, sea fans, lobsters, and many other animal and plant species. Throughout these fragile habitats, colorful fishes swim, feed, court, and thrive. Sea turtles−−once so numerous they inspired Spanish explorer Ponce de León to name these islands “Las Tortugas” in 1513−−still live in these waters. Loggerhead and Green sea turtles crawl onto sand beaches here to lay hundreds of eggs. -

Ecological Indicators for Assessing and Communicating Seagrass Status and Trends in Florida Bay§ Christopher J

Ecological Indicators 9S (2009) S68–S82 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ecological Indicators journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ecolind Ecological indicators for assessing and communicating seagrass status and trends in Florida Bay§ Christopher J. Madden a,*, David T. Rudnick a, Amanda A. McDonald a, Kevin M. Cunniff b, James W. Fourqurean c a Everglades Division, South Florida Water Management District, 8894 Belvedere Rd., West Palm Beach, FL 33411, USA b R.C.T. Engineering, Inc., 701 Northpoint Parkway, West Palm Beach, FL 33407, USA c Dept. of Biological Sciences and Southeast Environmental Research Center, Florida International University, Miami, FL 33199, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: A suite of seagrass indicator metrics is developed to evaluate four essential measures of seagrass Received 23 April 2008 community status for Florida Bay. The measures are based on several years of monitoring data using the Received in revised form 20 January 2009 Braun-Blanquet Cover Abundance (BBCA) scale to derive information about seagrass spatial extent, Accepted 11 February 2009 abundance, species diversity and presence of target species. As ecosystem restoration proceeds in south Florida, additional freshwater will be discharged to Florida Bay as a means to restore the bay’s hydrology Keywords: and salinity regime. Primary hypotheses about restoring ecological function of the keystone seagrass Florida Bay community are based on the premise that hydrologic restoration will increase environmental variability Seagrass and reduce hypersalinity. This will create greater niche space and permit multiple seagrass species to co- Status Indicators exist while maintaining good environmental conditions for Thalassia testudinum, the dominant climax Thalassia seagrass species. -

Bookletchart™ Intracoastal Waterway – Bahia Honda Key to Sugarloaf Key NOAA Chart 11445

BookletChart™ Intracoastal Waterway – Bahia Honda Key to Sugarloaf Key NOAA Chart 11445 A reduced-scale NOAA nautical chart for small boaters When possible, use the full-size NOAA chart for navigation. Published by the The tidal current at the bridge has a velocity of about 1.4 to 1.8 knots. Wind effects modify the current velocity considerably at times; easterly National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration winds tend to increase the northward flow and westerly winds the National Ocean Service southward flow. Overfalls that may swamp a small boat are said to occur Office of Coast Survey near the bridge at times of large tides. (For predictions, see the Tidal Current Tables.) www.NauticalCharts.NOAA.gov Route.–A route with a reported controlling depth of 8 feet, in July 1975, 888-990-NOAA from the Straits of Florida via the Moser Channel to the Gulf of Mexico is as follows: From a point 0.5 mile 336° from the center of the bridge, What are Nautical Charts? pass 200 yards west of the light on Red Bay Bank, thence 0.4 mile east of the light on Bullard Bank, thence to a position 3 miles west of Northwest Nautical charts are a fundamental tool of marine navigation. They show Cape of Cape Sable (chart 11431), thence to destination. water depths, obstructions, buoys, other aids to navigation, and much Bahia Honda Channel (Bahia Honda), 10 miles northwestward of more. The information is shown in a way that promotes safe and Sombrero Key and between Bahia Honda Key on the east and Scout efficient navigation. -

Federal Register/Vol. 63, No. 158/Monday, August 17, 1998

43870 Federal Register / Vol. 63, No. 158 / Monday, August 17, 1998 / Rules and Regulations U.S.C. 553) because: (1) The 1998±99 SUMMARY: The National Oceanic and effective July 1, 1997, and codified at 15 fiscal year began on July 1, 1998, and Atmospheric Administration amends CFR Part 922, Subpart P. the marketing order requires that the the regulations for the Florida Keys In September 1997, NOAA became rate of assessment for each fiscal year National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS or aware that significant injury to, and apply to all assessable papayas handled Sanctuary) to reinstate and make destruction of, living coral on the during such fiscal year; (2) the permanent the temporary prohibition on Tortugas Bank, west of the Dry Tortugas Committee needs to have sufficient anchoring by vessels 50 meters or National Park, was being caused by the funds to pay its expenses which are greater in registered length on Tortugas anchoring of vessels 50 meters or greater incurred on a continuous basis; and (3) Bank. The preamble to this rule contains in registered length. handlers are aware of this action which an environmental assessment for this Section 922.165 of the Sanctuary was recommended by the Committee at action. The intent of this rule is to regulations provides that, where a public meeting and is similar to other protect the coral reef at Tortugas Bank. necessary to prevent or minimize the assessment rate actions issued in past The proposed rule was published on destruction of, loss of, or injury to a years. February 11, 1998 and the comment Sanctuary resources, any and all List of Subjects in 7 CFR Part 928 period ended on March 13, 1998. -

Keys Sanctuary 25 Years of Marine Preservation National Parks Turn 100 Offbeat Keys Names Florida Keys Sunsets

Keys TravelerThe Magazine Keys Sanctuary 25 Years of Marine Preservation National Parks Turn 100 Offbeat Keys Names Florida Keys Sunsets fla-keys.com Decompresssing at Bahia Honda State Park near Big Pine Key in the Lower Florida Keys. ANDY NEWMAN MARIA NEWMAN Keys Traveler 12 The Magazine Editor Andy Newman Managing Editor 8 4 Carol Shaughnessy ROB O’NEAL ROB Copy Editor Buck Banks Writers Julie Botteri We do! Briana Ciraulo Chloe Lykes TIM GROLLIMUND “Keys Traveler” is published by the Monroe County Tourist Development Contents Council, the official visitor marketing agency for the Florida Keys & Key West. 4 Sanctuary Protects Keys Marine Resources Director 8 Outdoor Art Enriches the Florida Keys Harold Wheeler 9 Epic Keys: Kiteboarding and Wakeboarding Director of Sales Stacey Mitchell 10 That Florida Keys Sunset! Florida Keys & Key West 12 Keys National Parks Join Centennial Celebration Visitor Information www.fla-keys.com 14 Florida Bay is a Must-Do Angling Experience www.fla-keys.co.uk 16 Race Over Water During Key Largo Bridge Run www.fla-keys.de www.fla-keys.it 17 What’s in a Name? In Marathon, Plenty! www.fla-keys.ie 18 Visit Indian and Lignumvitae Keys Splash or Relax at Keys Beaches www.fla-keys.fr New Arts District Enlivens Key West ach of the Florida Keys’ regions, from Key Largo Bahia Honda State Park, located in the Lower Keys www.fla-keys.nl www.fla-keys.be Stroll Back in Time at Crane Point to Key West, features sandy beaches for relaxing, between MMs 36 and 37. The beaches of Bahia Honda Toll-Free in the U.S. -

Dry Tortugas National Park Monroe County, Florida

APPENDIX A: ERRATA 1. Page 63, Commercial Services, second paragraph. Replace the second sentence with the following text: “The number of vessels used in the operation, and arrival and departure patterns at Fort Jefferson, will be determined in the concession contracting process.” Explanation: The number of vessels to be used by the ferry concessionaire, and appropriate arrival and departure patterns, will be determined during the concessions contracting process that will occur during implementation of the Final GMPA/EIS. 2. Page 64, Commercial Services, third paragraph. Change the last word of the fourth sentence from “six” to “twelve.” Explanation: Group size for snorkeling and diving with commercial guides in the research natural area zone will be limited to 12 passengers, rather than 6 passengers. 3. Page 64, Commercial Services, sixth paragraph. Change the fourth sentence to read: “CUA permits will be issued to boat operators for 12-passenger multi-day diving trips.” Explanation: Group size for guided multi-day diving trips by operators with Commercial Use Authorizations will be 12 passengers, rather than 6 passengers. 4. Page 40, Table 1. Ranges of Visitor Use At Specific Locations. Change the last sentence in the box on page 40 to read: “Group size for snorkeling and diving with commercial guides in waters in the research natural area shall be a maximum of 12 passengers, excluding the guide.” Explanation: Clarifies that maximum group size for guided multi-day diving trips in the RNA by operators with Commercial Use Authorizations will be 12 passengers, rather than six passengers. 5. Page 84, Table 4: Summary of Alternative Actions. -

Climate Change and Florida's National Parks

Climate Change and Florida’s National Parks Florida is among the most climate change-threatened states in the United States. Florida’s treasured national parks—spanning the Greater Everglades ecosystem northward into Gulf Islands National Seashore and beyond—are being impacted by our changing climate. Climate change is the greatest threat science-based policies that enhance the Florida’s economy. NPCA’s Sun Coast America’s national parks have ever faced. resilience of our incredible system of region is systematically assessing, through Nearly everything we know and love about national parks. With Florida’s low elevation, research and analysis, the most serious the parks—their plants and animals, rivers national park sites in the state are especially climate impacts threatening national and lakes, beaches, historic structures, susceptible to the threats associated with park landscapes. This regional climate and more—is already under stress from climate change. Sea level rise, changing dispatch thus serves a twofold purpose: to our changing climate. As America’s ocean conditions, and shifting weather shine a light on climate case studies across leading voice for our national parks, patterns are impacting our landscapes. iconic Floridian places, and to share what National Parks Conservation Association All of these climate impacts converge to NPCA’s Sun Coast team is doing to help (NPCA) is at the forefront of efforts to present unprecedented challenges to park address and adapt to climate threats to address climate impacts and promote management, preservation, tourism, and our treasured national park ecosystems. Above: Florida Bay in Everglades National Park ©South Florida Water Management District NATIONAL PARK Rising Sea Levels Threaten THREAT Biodiversity & Cultural Resources While all national park units in Florida Importance, Everglades National Park are threatened by sea level rise, some protects an abundance of biodiversity parks are more vulnerable than others. -

• the Seven Mile Bridge (Knight Key Bridge HAER FL-2 Moser Channel

The Seven Mile Bridge (Knight Key Bridge HAER FL-2 Moser Channel Bridge Pacet Channel Viaduct) Linking Several Florida Keys Monroe County }-|/ -i c,.^ • Florida '■ L. f'H PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Engineering Record National Park Service Department of the Interior Washington D.C. 20240 • THE SEVEN MILE BRIDGE FL-2 MA e^ Ft. A HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD THE SEVEN MILE BRIDGE (Knight Key Bridge-Pigeon Key Bridge-Moser Channel Bridge- Pacet Channel Viaduct) Location: Spanning several Florida Keys and many miles of water this bridge is approximately 110 miles from Miami. It begins at Knight Key at the northeast end and terminates at Pacet Key at the southwest end. UTM 487,364E 476.848E 2,732,303N 2,729,606N # Date of Construction 1909-1912 as a railway bridge. Adapted as a concrete vehicular bridge on U.S. I in 1937-1938. Present Owner: Florida Department of Transpor- tation Hayden Burns Building Tallahassee, Florida 32304 Present Use: Since its conversion as a bridge for vehicles it has been in con- tinually heavy use as U.S. I linking Miami with Key West. There is one through draw span riAcis. rLi— z. \r. z.) at Moser Channel, the connecting channel between the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico. It is presently scheduled to be replaced by the State with con- struction already underway in 1980. Significance At the time the Florida East Coast Railway constructed this bridge it was acclaimed as the longest bridge in the world, an engineering marvel. It we.s the most costly of all Flagler's bridges in the Key West Exten- sion. -

Mississippi Canyon 252 Incident Baseline Sediment and Water Collection and Analyses for NRDA Purposes in Florida Keys APPROVED

Mississippi Canyon 252 Incident Baseline Sediment and Water Collection and Analyses for NRDA Purposes in Florida Keys Approval of this work plan is for the purposes of obtaining data for the Natural Resource Damage Assessment. Parties each reserve its right to produce its own independent interpretation and analysis of any data collected pursuant to this work plan APPROVED: . ZOVO BP Representative! 7 Date: m/jfo 'AA/Trustee Representative: 1 060410 Final DWH-AR0013591 Florida Keys Baseline Sampling Plan for Water and Sediment BACKGROUND The Florida Keys extend approximately 220 nautical miles from the southern tip of the Florida peninsula, southwest to the Dry Tortugas. The Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, which surrounds the Keys, covers 2,900 square nautical miles of coastal waters, overlaps four national wildlife refuges, six state parks, and three state aquatic preserves. In addition, three national parks share boundaries with the Sanctuary. The Florida Keys marine ecosystem supports over 6,000 species of plants, fishes, and invertebrates, including the nation’s only living coral reef that lies adjacent to the continent. The area also includes extensive seagrass communities, mangrove islands and fringes, and some of the most significant maritime heritage and historical resources of any coastal community in the nation. In addition, the region’s natural resources provide livelihoods for many of the nearly 80,000 residents, and provide recreation for visitors totaling approximately thirteen million visitor-days each year. In order to proactively begin the steps of the Natural Resource Damage Assessment (NRDA) process, planning was initiated to determine the protocols and sampling sites that would be used for the collection of baseline water and sediment samples. -

South Florida National Park Sites

National Park Service National Parks and Preserves U.S. Department of the Interior of South Florida Ranger Station Interpretive Trail Bear Island Alligator Alley (Toll Road) Campground Primitive Camping Rest Area, F 75 75 foot access only l o ri Gasoline Lodging and Meals da to Naples N a No Access to/from t i o Alligator Alley n Restrooms Park Area Boundary a 839 l S c Picnic Area e Public Boat Ramp n i SR 29 c T r Marina a il to Naples 837 Big Cypress 837 National Preserve 1 Birdon Road Turner River Road River Turner 41 841 Big Cypress Visitor Center EVERGLADES 41 821 CITY Gulf Coast Visitor Center Tree Snail Hammock Nature Trail Tamiami Trail Krome Ave. MIAMI 41 Loop Road Shark Valley Visitor Center Florida's Turnpike Florida's 1 SW 168th St. Chekika Everglades Biscayne SR 997 National Park National Park HOMESTEAD Boca Chita Key Exit 6 Dante Fascell Pinelands Visitor Center Pa-hay-okee Coe Gulf of Mexico Overlook N. Canal Dr. Visitor (SW 328 St.) Center Elliott Key 9336 Long Pine Key (Palm Dr.) Mahogany 1 Hammock Royal Palm Visitor Center Anhinga Trail Gumbo Limbo Trail West Lake Atlantic Ocean Flamingo Visitor Center Key Largo Fort Jefferson Florida Bay 1 North Dry Tortugas 0 5 10 Kilometers National Park 05 10 Miles 0 2 4 70 miles west of Key West, Note: This map is not a substitute for an Miles by plane or boat only. up-to-date nautical chart or hiking map. Big Cypress, Biscayne, Dry Tortugas, and Everglades Phone Numbers Portions of Biscayne and 95 826 Everglades National Parks National Park Service Website: http://www.nps.gov 95 Florida Turnpike Florida Tamiami Trail Miami Important Phone Numbers 41 41 Shark Valley 826 Visitor Center 1 Below is a list of phone numbers you may need to help plan your trip to the 874 south Florida national parks and preserves. -

Tortugas Ecological Reserve

Strategy for Stewardship Tortugas Ecological Reserve U.S. Department of Commerce DraftSupplemental National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Environmental National Ocean Service ImpactStatement/ Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management DraftSupplemental Marine Sanctuaries Division ManagementPlan EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS), working in cooperation with the State of Florida, the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council, and the National Marine Fisheries Service, proposes to establish a 151 square nautical mile “no- take” ecological reserve to protect the critical coral reef ecosystem of the Tortugas, a remote area in the western part of the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. The reserve would consist of two sections, Tortugas North and Tortugas South, and would require an expansion of Sanctuary boundaries to protect important coral reef resources in the areas of Sherwood Forest and Riley’s Hump. An ecological reserve in the Tortugas will preserve the richness of species and health of fish stocks in the Tortugas and throughout the Florida Keys, helping to ensure the stability of commercial and recreational fisheries. The reserve will protect important spawning areas for snapper and grouper, as well as valuable deepwater habitat for other commercial species. Restrictions on vessel discharge and anchoring will protect water quality and habitat complexity. The proposed reserve’s geographical isolation will help scientists distinguish between natural and human-caused changes to the coral reef environment. Protecting Ocean Wilderness Creating an ecological reserve in the Tortugas will protect some of the most productive and unique marine resources of the Sanctuary. Because of its remote location 70 miles west of Key West and more than 140 miles from mainland Florida, the Tortugas region has the best water quality in the Sanctuary. -

Biscayne National Park, Florida

National Park Service Biscayne U.S. Department of the Interior Camping Guide to Biscayne National Park Boca Chita Key Tent camping is permitted in designated areas on Elliott and Boca Chita Keys. These islands are accessible by boat only. Camping is limited to fourteen (14) consecutive days or no more than thirty (30) days within a calendar year. Reservations are not accepted. The sites are available on a first-come, first-served basis. No services are available on the islands. Facilities Elliott Key: Freshwater toilets, cold water showers, and drinking water are available. Boca Chita Key: Saltwater toilets are available. Sinks, showers and drinking water are NOT available. Fees There is a $15 per night per campsite camping fee. The fee includes a standard campsite (up to 6 people and 2 tents). If docking a boat overnight, there is a $20 fee that includes one night camping. Group campsites (30 people and 5 tents) are $30 per night on Elliott Key. Group campsite is available by reservation only (305) 230-1144 x 008. Holders of the Interagency Senior or Access passes receive a 50% discount on camping and marina use fees. The fee is paid at the self- service fee station on each island. It is your responsibility to make sure that your fees are paid. NPS rangers will verify payment compliance. Camping/marina use fees must be paid PRIOR to 5 p.m. daily. Anyone who arrives after 5 p.m. must pay camping/ marina use fees immediately upon arrival. Any vessel in the harbor after 5 p.m.