Introduction to the Great Polish Map of Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

15 Station Road Eddleston, Peeblesshire 15 Station Road Eddleston Peeblesshire

15 STATION ROAD EDDLESTON, PEEBLESSHIRE 15 STATION ROAD EDDLESTON PEEBLESSHIRE Peebles about 4 miles Edinburgh about 18 miles A charming ‘B’ listed mid-terraced house located in the conservation area of the quiet picturesque village of Eddleston. Accommodation comprises: 2 double bedrooms, single guest bedroom/study, 2 reception rooms, kitchen, shower room, family bathroom. • Peaceful rural location • Excellent location for commuting to Edinburgh • Regular bus links to Edinburgh, Peebles and beyond and within 200 yards of the bus stop • Local primary school • Mature secluded rear garden CKD Galbraith 59 George Street Edinburgh EH2 2JG 0131 240 6960 [email protected] OFFICES ACROSS SCOTLAND GENERAL 15 Station Road is situated about 4 miles north of the county town of Peebles at Eddleston off the A703. Eddleston is a small picturesque village with its own primary school, church, hotel and village hall. There is a regular bus service to Edinburgh/Peebles and neighbouring towns. Peebles is the county town set within an area of outstanding beauty. It offers its own unique blend of entertainment, sports and leisure. There is a good choice of restaurants and bars and the town has its own swimming pool, fitness centre, tennis courts and golf course. The Tweed Cycleway, the Southern Upland Way and Glentress Forest nearby provide superb opportunities for walking and mountain biking. Peebles has a High School, a choice of primary schools, a varied selection of shops and a popular library. DESCRIPTION 15 Station Road is a ‘B’ Listed mid-terraced stone house that was built in approximately 1750. The property has been extended and offers very comfortable and well laid out accommodation. -

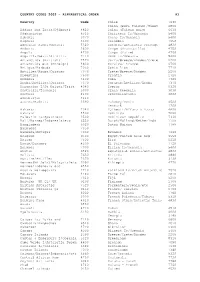

Country Codes 2002 – Alphabetical Order A1

COUNTRY CODES 2002 – ALPHABETICAL ORDER A1 Country Code Chile 7640 China (excl Taiwan)/Tibet 6800 Affars and Issas/Djibouti 4820 China (Taiwan only) 6630 Afghanistan 6510 Christmas Is/Oceania 5400 Albania 3070 Cocos Is/Oceania 5400 Algeria 3500 Colombia 7650 American Samoa/Oceania 5320 Comoros/Antarctic Foreign 4830 Andorra 2800 Congo (Brazzaville) 4750 Angola 4700 Congo (Zaire) 4760 Anguilla/Nevis/St Kitts 7110 Cook Is/Oceania 5400 Antarctica (British) 7520 Corfu/Greece/Rhodes/Crete 2200 Antarctica etc (Foreign) 4830 Corsica/ France 0700 Antigua/Barbuda 7030 Costa Rica 7710 Antilles/Aruba/Curacao 7370 Crete/Greece/Rhodes 2200 Argentina 7600 Croatia 2720 Armenia 3100 Cuba 7320 Aruba/Antilles/Curacao 7370 Curacao/Antilles/Aruba 7370 Ascension I/St Helena/Trist 4040 Cyprus 0320 Australia/Tasmania 5000 Czech Republic 3030 Austria 2100 Czechoslovakia 3020 Azerbaijan 3110 Azores/Madeira 2390 Dahomey/Benin 4500 Denmark 1200 Bahamas 7040 Djibouti/Affars & Issas 4820 Bahrain 5500 Dominica 7080 Balearic Is/Spain/etc 2500 Dominican Republic 7330 Bali/Borneo/Indonesia/etc 6550 Dutch/Holland/Netherlnds 1100 Bangladesh 6020 Dutch Guiana 7780 Barbados 7050 Barbuda/Antigua 7030 Ecuador 7660 Belgium 0500 Egypt/United Arab Rep 3550 Belize 7500 Eire 0210 Benin/Dahomey 4500 El Salvador 7720 Bermuda 7000 Ellice Is/Oceania 5400 Bhutan 6520 Equatorial Guinea/Antarctic 4830 Bolivia 7630 Eritrea 4840 Bonaire/Antilles 7370 Estonia 3130 Borneo(NE Soln)/Malaysia/etc 6050 Ethiopia 4770 Borneo/Indonesia etc 6550 Bosnia Herzegovina 2710 Falkland Is/Brtsh Antarctic -

PLANTS of PEEBLESSHIRE (Vice-County 78)

PLANTS OF PEEBLESSHIRE (Vice-county 78) A CHECKLIST OF FLOWERING PLANTS AND FERNS David J McCosh 2012 Cover photograph: Sedum villosum, FJ Roberts Cover design: L Cranmer Copyright DJ McCosh Privately published DJ McCosh Holt Norfolk 2012 2 Neidpath Castle Its rocks and grassland are home to scarce plants 3 4 Contents Introduction 1 History of Plant Recording 1 Geographical Scope and Physical Features 2 Characteristics of the Flora 3 Sources referred to 5 Conventions, Initials and Abbreviations 6 Plant List 9 Index of Genera 101 5 Peeblesshire (v-c 78), showing main geographical features 6 Introduction This book summarises current knowledge about the distribution of wild flowers in Peeblesshire. It is largely the fruit of many pleasant hours of botanising by the author and a few others and as such reflects their particular interests. History of Plant Recording Peeblesshire is thinly populated and has had few resident botanists to record its flora. Also its upland terrain held little in the way of dramatic features or geology to attract outside botanists. Consequently the first list of the county’s flora with any pretension to completeness only became available in 1925 with the publication of the History of Peeblesshire (Eds, JW Buchan and H Paton). For this FRS Balfour and AB Jackson provided a chapter on the county’s flora which included a list of all the species known to occur. The first records were made by Dr A Pennecuik in 1715. He gave localities for 30 species and listed 8 others, most of which are still to be found. Thereafter for some 140 years the only evidence of interest is a few specimens in the national herbaria and scattered records in Lightfoot (1778), Watson (1837) and The New Statistical Account (1834-45). -

Elaborated Business Case Eddleston Water Deliverable of Work Package 5 - Upscaling Date: 20-08-2020 Status: Final

Elaborated business case Eddleston Water Deliverable of Work Package 5 - Upscaling Date: 20-08-2020 Status: Final Photo by C. Spray. Colophon Building with Nature – Elaborated business case Eddleston Water Deliverable of Work Package 5 – Upscaling Part of the INTERREG Building with Nature project https://northsearegion.eu/building-with-nature/ Authors University of Dundee – Prof. Christopher Spray Royal HaskoningDHV – Jasper Fiselier Royal HaskoningDHV – Simeon Moons WP5 Project Leader EcoShape – Erik van Eekelen 20-08-2020 Contents Contents ................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Summary ................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Case description ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 Stakeholder and voluntary participation .............................................................................................................. 11 Ecosystem service benefits ................................................................................................................................... 13 Lessons learned ................................................................................................................................................... -

I General Area of South Quee

Organisation Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Address Line3 City / town County DUNDAS PARKS GOLFGENERAL CLUB- AREA IN CLUBHOUSE OF AT MAIN RECEPTION SOUTH QUEENSFERRYWest Lothian ON PAVILLION WALL,KING 100M EDWARD FROM PARK 3G PITCH LOCKERBIE Dumfriesshire ROBERTSON CONSTRUCTION-NINEWELLS DRIVE NINEWELLS HOSPITAL*** DUNDEE Angus CCL HOUSE- ON WALLBURNSIDE BETWEEN PLACE AG PETERS & MACKAY BROS GARAGE TROON Ayrshire ON BUS SHELTERBATTERY BESIDE THE ROAD ALBERT HOTEL NORTH QUEENSFERRYFife INVERKEITHIN ADJACENT TO #5959 PEEL PEEL ROAD ROAD . NORTH OF ENT TO TRAIN STATION THORNTONHALL GLASGOW AT MAIN RECEPTION1-3 STATION ROAD STRATHAVEN Lanarkshire INSIDE RED TELEPHONEPERTH ROADBOX GILMERTON CRIEFFPerthshire LADYBANK YOUTHBEECHES CLUB- ON OUTSIDE WALL LADYBANK CUPARFife ATR EQUIPMENTUNNAMED SOLUTIONS ROAD (TAMALA)- IN WORKSHOP OFFICE WHITECAIRNS ABERDEENAberdeenshire OUTSIDE DREGHORNDREGHORN LOAN HALL LOAN Edinburgh METAFLAKE LTD UNITSTATION 2- ON ROAD WALL AT ENTRANCE GATE ANSTRUTHER Fife Premier Store 2, New Road Kennoway Leven Fife REDGATES HOLIDAYKIRKOSWALD PARK- TO LHSROAD OF RECEPTION DOOR MAIDENS GIRVANAyrshire COUNCIL OFFICES-4 NEWTOWN ON EXT WALL STREET BETWEEN TWO ENTRANCE DOORS DUNS Berwickshire AT MAIN RECEPTIONQUEENS OF AYRSHIRE DRIVE ATHLETICS ARENA KILMARNOCK Ayrshire FIFE CONSTABULARY68 PIPELAND ST ANDREWS ROAD POLICE STATION- AT RECEPTION St Andrews Fife W J & W LANG LTD-1 SEEDHILL IN 1ST AID ROOM Paisley Renfrewshire MONTRAVE HALL-58 TO LEVEN RHS OFROAD BUILDING LUNDIN LINKS LEVENFife MIGDALE SMOLTDORNOCH LTD- ON WALL ROAD AT -

Eddleston Water Restoration Project Macroinvertebrate Responses 2012-2019 Tweed Forum APEM Ref: P00002209 June 2020

Eddleston Water Restoration Project Macroinvertebrate responses 2012-2019 Tweed Forum APEM Ref: P00002209 June 2020 Client: Tweed Forum Address: South Court Drygrange Steading Melrose Roxburghshire TD6 9DJ Project reference: P00002209 Date of issue: 27 June 2020 ________________________ Project Director: Dr David Bradley Project Manager: Dr Andrew Davey Laboratory Manager: Sally Donaldson ________________________ APEM Ltd Riverview A17 Embankment Business Park Heaton Mersey Stockport SK4 3GN Tel: 0161 442 8938 Fax: 0161 432 6083 Registered in England No. 02530851 Report should be cited as: “APEM (2020). Eddleston Water Restoration Project: Macroinvertebrate responses 2012- 2019. APEM Scientific Report P00002009. Tweed Foundation, June 2020, v3.0 Final Report, 32 pp.” Registered in England No. 2530851, Registered Address Riverview A17 Embankment Business Park, Heaton Mersey, Stockport, SK4 3GN Registered in England No. 2530851, Registered Address Riverview A17 Embankment Business Park, Heaton Mersey, Stockport, SK4 3GN Revision and Amendment Register Version Date Sections Pages Summary of Changes Approved by Number 1.0 09/04/2020 1 25 Interim report with D. Bradley summary of main findings 2.0 11/06/2020 4 28 Draft final report D. Bradley 3.0 30/06/2020 4 32 Final report addressing D. Bradley comments from J. Dodd. Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ 1 1. Introduction and Methods ................................................................................................ -

Tweeddale Community Directory Is Produced by the Bridge Tweeddale

This Tweeddale Community Directory is produced by The Bridge Tweeddale. Information was collected during 2016/17. New editions are printed approximately every two years. A copy of the Directory is also published on The Bridge Website – www.the-bridge.uk.net – under publications. This will be regularly updated and any updated information will also be available in The Volunteer Resource Centre in Peebles. Please use the sheet at the back of the Directory to inform us of any changes or omissions. The Bridge is part of a national network of Councils for Voluntary Service. We aim to represent and support the voluntary sector and to assist local organisations to get together for common purposes. We look to enable local people to gain access to decision-making processes which affect their lives and their communities. The Bridge Tweeddale manages and provides the following services through our Volunteer Resource Centre: - Tweed Wheels project, with an accessible community minibus for local groups and a disabled passenger community car for hire by local residents - Tweeddale Thrift Shop, Innerleithen, selling and recycling clothes and other goods to support Tweed Wheels and our other services - Meeting rooms - shared office accommodation - cost-price clerical services, such as publicity production, photocopying, typing, laminating and spiral binding - loan of equipment, including digital projector, overhead projector, flip chart, display boards, tables and sandwich board We can provide information and advice on writing constitutions and management structures, where to go for funding and how to write a grant application. We organise training events on a variety of issues. Through our quarterly newsletter, we provide opportunities to share information about and for local community and voluntary organisations. -

Eddleston Water Appraisal Report

Peebles Flood Study - Eddleston Water Appraisal Report Final Report January 2019 Council Headquarters Newtown St Boswells Melrose Scottish Borders TD6 0SA JBA Project Manager Angus Pettit Unit 2.1 Quantum Court Research Avenue South Heriot Watt Research Park Riccarton Edinburgh EH14 4AP UK Revision History Revision Ref / Date Issued Amendments Issued to S0-P01.03 / October 2018 - Angus Pettit S0-P01 Minor amendments S4-P01 / October 2018 - Scottish Borders Council S4-P02 / January 2019 - Scottish Borders Council / SEPA Contract This report describes work commissioned by Duncan Morrison, on behalf of Scottish Borders Council, by a letter dated 16 January 2017. Scottish Borders Council's representative for the contract was Duncan Morrison). Tasmin Fletcher, Barney Bedford, Hannah Otton and Christina Kampanou of JBA Consulting carried out this work. Prepared by .................................................. Barney Bedford BSc MSc Analyst Reviewed by ................................................. Angus Pettit BSc MSc CEnv CSci MCIWEM C.WEM Technical Director Purpose This document has been prepared as a Final Report for Scottish Borders Council. JBA Consulting accepts no responsibility or liability for any use that is made of this document other than by the Client for the purposes for which it was originally commissioned and prepared. JBA Consulting has no liability regarding the use of this report except to Scottish Borders Council. Our work has followed accepted procedure in providing the services but given the residual risk associated with any prediction and the variability which can be experienced in flood conditions, we can take no liability for the consequences of flooding in relation to items outside our control or agreed scope of service. -

Notes on the Early History of the Kidston Family in Scotland

NOTES ON THE EARLY HISTORY OF THE KIDSTON FAMILY IN SCOTLAND By: Robert D. Davic, Ph.D.; [email protected]. Pittsburgh, PA, USA; (March 17, 2015 revision) ===================================================================================== INTRODUCTION This document is a summary of notes my wife and I have gathered about the early history of her Kidston family ancestry from Scotland. My wife, Elizabeth Kidston Davic (b. 1951, m. 1974) was born in the U.S.A. in western Pennsylvania, second child of Richard Kidston and Gladys Thomas. She always knew that both of her father’s grandparents came from Scotland, but had few details. After retirement, and with more time to get involved with her Kidston ancestry, she obtained information about her grandfather’s family and made a visit to his home town of Glasglow. She became aware of a remarkable document written by a distant cousin, John Kidston Tait (b. 1924, d. 2013), that gave a detailed record of her Scottish ancestry back to her 12th great grandfather, John Kydstoun of Logie parish, Sterlingshire (Tait, 1995: The Kidstons’ of Logie; 1995 edition, 20 Chapters, 4 Addendum). Information provided by Mr. Tait revealed that the Kidston family name had a much older presence at the town of Peebles located in the lowland county of Peeblesshire. Seen today on road maps of Peebles are the place locations Upper Kidston, Nether Kidston, Kidston Mill, Kidston Burn (a stream), and Kidston Bank Woods. Expecting to find some Kidston relatives living at Peebles to contact for information about family history, you can imagine our surprise when we learned that no Kidstons’ have lived at Peebles for more than 700 years. -

Eddleston Water: Environment Agency

Eddleston Water Project: introduction to research aims & monitoring Partnership project, begun in 2009 Eddleston Water: Environment Agency • Eddleston Water scoping study • Eddleston Water restoration Phase II HNS NFU(S) • Eddleston Water restoration Phase III Tweed Foundation Forest Research Cbec Ltd Chris Spray, Alan Werritty, Tom Ball, Andrew Black, Michael Bonell, Nicole Archer & students Eddleston Water catchment – 69 sq km • Main river flows c 17 kms North-South in to the Tweed at Peebles • Largely rural with two settlements – Eddleston and Peebles • Long history of river and flood plain management – for agriculture mainly – and of flooding (1723, 1777, 1792, 1831, 1846, 1865, 1881, 1891, 1897, 1908, 1914, 1926, 1948, 1956, 1977, 1986, 1988, 1991, 1997, 2000, 2005) • EU Conservation status as SAC for Ranunculus type river, and Atlantic Salmon, Lampreys and Otters. SSSI interest also on beetles of riverine gravels • Fails WFD status for Morphology (bad) and for aquatic macrophytes (moderate) Policy drivers for river restoration: Eddleston Water Two main policy drivers: • EC Water Framework Directive => Water Environment and Water Services (Scotland) Act 2003: Eddleston Water characterised as having “poor” ecological status • EC Directive on the Assessment and Management of Floods => Flood Risk Management (Scotland) Act 2009: section 20 requires SEPA to assess whether the “alteration ... or restoration of natural features and characteristics ... could contribute to management of flood risk” often referred to as natural flood management -

KILRUBIE a Survey Project Undertaken by Peeblesshire

KILRUBIE A Survey Project undertaken by Peeblesshire Archaeological Society in conjunction with Scotland's Rural Past Jack Boughey March 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To the SRP (Scotland's Rural Past) Team of... Dr Tertia Barnett, Danny Dutton, Kirsty MacDonald, Ishbel MacKinnon and Brian Wilkinson for their assistance with on the ground training, excellently structured formal training days, loan of equipment, and best of all their help and advice delivered with patience and unfailing good humour. To Peeblesshire Archaeology Team Members... Gillian Brown, Peter Barclay, Jeff Carter, Trevor Cowie, Piers Dixon, David Drurie, Joyce Durham, Maureen Erasmusson, Bill Glass, Kathy Henry, Strat Halliday, Alan Herd, Peter Jack, Michael Jones, Bob Knox and Gordon Stephen for braving the elements, and whether teaching or learning, contributing to both the survey and the research strands which build to this report, with special thanks to Joyce Durham for the excellent drawings in this report, and Trevor Cowie for reviewing and editing the Report. Finally, we are grateful to Archie Smellie, Hattonknowe Farm, for permitting us access to his land for this survey. Table of Contents 1. Introduction and Objectives 2. The Archaeological Objective 2.1 Summary 2.2 Location 2.3 Survey 2.4 Overview of Farmstead 2.4.i Old Trackway 2.4.ii Farm Buildings 2.4.iii Lazy Beds 2.4.iv Garden Plot 2.4.v Enclosures 2.4.vi March Dyke 2. 5 Research Strands 2.5.i Historical Mapping 2.5.ii Census Returns 2.5.iii Hearth Tax 2.5.iv Horse Tax 2.5.v Name Derivation 2.5.vi Artefacts 2.5.vii Other Research 3. -

The Eddleston Waterproject

The Eddleston Water The Eddleston Water is a small tributary of the River Tweed, flowing 20 km north to south before reaching the main river in the town of Peebles. Over time, the course of the river has been extensively altered and long sections were straightened in the early 19th century to improve agricultural production. Other changes in land The Eddleston management, both in the river valley and on the surrounding hill slopes, have also altered how the land drains. Together, these changes have resulted in an increased risk of flooding to Eddleston and Peebles, as rainfall and flood waters travel ever more quickly and directly from the hill slopes and along the river channels towards Water project these communities. At the same time, these changes have also damaged the river Restoring natural habitats environment itself, leading to reduced water course length and habitat loss for and reducing flood risk plants and animals, including salmon and trout, as well as rare and protected species such as otters and lampreys. Project aims The three main aims are to: • investigate the possibility of reducing flood risk to the communities of Eddleston and Peebles by restoring some of the original natural features of the river, its floodplain and surrounding hill slopes; • examine the potential to improve the river habitat for wildlife and fisheries; • work with landowners and communities in the Eddleston valley to maximise the benefits they would gain from such work, while maintaining the profitability of local farms. Who is involved? The project is a partnership initiative led by the Tweed Forum, with contributions from the University of Dundee and supported by Scottish Borders Council, the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA), the Scottish Government and British Geological Survey.