The Edinburgh Edition of Sidney's "Arcadia."

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edward De Vere and the Two Shrew Plays

The Playwright’s Progress: Edward de Vere and the Two Shrew Plays Ramon Jiménez or more than 400 years the two Shrew plays—The Tayminge of a Shrowe (1594) and The Taming of the Shrew (1623)—have been entangled with each other in scholarly disagreements about who wrote them, which was F written first, and how they relate to each other. Even today, there is consensus on only one of these questions—that it was Shakespeare alone who wrote The Shrew that appeared in the Folio . It is, as J. Dover Wilson wrote, “one of the most diffi- cult cruxes in the Shakespearian canon” (vii). An objective review of the evidence, however, supplies a solution to the puz- zle. It confirms that the two plays were written in the order in which they appear in the record, The Shrew being a major revision of the earlier play, A Shrew . They were by the same author—Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, whose poetry and plays appeared under the pseudonym “William Shakespeare” during the last decade of his life. Events in Oxford’s sixteenth year and his travels in the 1570s support composition dates before 1580 for both plays. These conclusions also reveal a unique and hitherto unremarked example of the playwright’s progress and development from a teenager learning to write for the stage to a journeyman dramatist in his twenties. De Vere’s exposure to the in- tricacies and language of the law, and his extended tour of France and Italy, as well as his maturation as a poet, caused him to rewrite his earlier effort and pro- duce a comedy that continues to entertain centuries later. -

Hier Finden Sie Vielerlei Fabelwesen, Die Frühe Drucker in Ihren Bücherzeichen Verwendeten

Hier finden Sie vielerlei Fabelwesen, die frühe Drucker in ihren Bücherzeichen verwendeten. B40b, 12.2015 Über Fabelwesen Einhörner Kentauren oder Zentauren Uroboros Nixen oder Meerjungfrauen Pegasus Wyvern Drachen Phoenix Kerberos Hippokampen Satyrn Sphinx Hippogryph Die Sibylle gleicht einer Harpyie Skylla Hydra Seeschlangen Chimaira Basilisken Über den Greif liegt eine eigene Datei vor – wie es dem Wappentier der Buchdrucker gebührt. Hier sind folgende Drucker mit ihren Fabelwesen vertreten Accademia degli Insensati Guillaume de Bret Peter Drach d.Ä. Familie Gourmont Daniel Adam William Bretton Cristoforo Draconi Richard Grafton Giorgio Angelieri Antonio Bulifon Compagnia del Drago Astolfo Grandi Thomas Anshelm Cuthbert Burby Heinrich Eckert Heinrich Gran Balthasar Arnoullet Vincenzo Busdraghi Guillaume Eustace Jean Granjon Henry Bynneman und Robert Granjon Conrad Bade Bartolomeo Faletti Johannes Gravius Nicolaus de Balaguer Girolamo Calepino Richard Fawkes Cristoforo Griffio Vittorio Baldini Prigent Calvarin Juan Ferrer Johannes Gymnich d.Ä. Robert Ballard d.Ä. Jean Calvet Sigmund Feyerabend Tommaso Ballarino Abraham Jansz Canin Miles Fletcher Hendrick Lodewycxsz Richard Bankes Juan de Canova François Fradin genannt Poitevin, van Haestens Barezzo Barezzi Giovanni Giacomo Carlino Constantin Fradin Joachim Heller Christopher Barker Giovanni Francesco Carrara und Pierre Fradin Pierre L’Huillier Girolami Bartoli Girolamo Cartolari Augustin Fries Guillaume Huyon Giovanni Bazachi Guillaume Cavellat Michael Furter Franz Behem Simon de Colines William und Isaac Jaggard Giovanni Francesco Besozzi Michael Colyn Andreas Geßner d.J. Juan Joffre Girolamo Biondo Comin da Trino und Hans Jakob Geßner Juan de Junta d.J Franz Birckmann Girolamo Concordia Johannes Friedrich Gleditsch Francoys Jansz Boels Vincenzo Conti Anselmo Giaccarelli Thielman Kerver d.Ä. Pellegrino Bonardi Domenico, Girolamo Johannes Kinck William Bonham John Danter und Luigi Giglio Johannes Knoblouch Hirolami Giberti Henry Denham Jacques Giunta d.Ä. -

A Rare Quarto Edition of Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet

A rare quarto edition of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet. London: Cuthbert Burby, 1599. 6 5/8 inches x 4 3/4 inches (168 mm x 121 mm), [92] pages, A–L4 M2. The | most ex= | cellent and lamentable | Tragedie, of Romeo | and Iuliet. | Newly corrected, augmented, and | amended: As it hath bene sundry times publiquely acted, by the | right Honourable the Lord Chamberlaine | his Seruants. | [Creede’s device] | London | Printed by Thomas Creede, for Cuthbert Burby, and are to | be sold at his shop neare the Exchange. | 1599. Shakespeare’s quartos, so named because of their format (a single sheet folded twice, creating four leaves or eight pages), are the first printed representations of his plays and, as none of the plays survives in manuscript, of great importance to Shakespeare scholarship. Only twenty-one of Shakespeare’s plays were published in quarto before the closure of the theaters and outbreak of civil war in 1642. These quartos were printed from either Shakespeare’s “foul papers” (a draft with notations and changes that was given in sections to actors for their respective roles); from “fair copies” created from foul papers that presented the entire action of the play; from promptbooks, essentially fair copies annotated and expanded by the author and acting company to clarify stage directions, sound effects, etc.; or from a previously published quarto edition. The quartos were inexpensive to produce and were published for various reasons, including to secure the acting company’s rights to the material and to bring in money during the plague years in London when the theaters were closed. -

Det. 1.2.2 Quartos 1594-1609.Pdf

author registered year of title printer stationer value editions edition Anon. 6 February 1594 to John 1594 The most lamentable Romaine tragedie of Titus Iohn Danter Edward White & "rather good" 1600, 1611 Danter Andronicus as it was plaide by the Right Honourable Thomas Millington the Earle of Darbie, Earle of Pembrooke, and Earle of Sussex their seruants Anon. 2 May 1594 1594 A Pleasant Conceited Historie, Called the Taming of Peter Short Cuthbert Burby bad a Shrew. As it was sundry times acted by the Right honorable the Earle of Pembrook his seruants. Anon. 12 March 1594 to Thomas 1594 The First Part of the Contention Betwixt the Two Thomas Creede Thomas Millington bad 1600 Millington Famous Houses of Yorke and Lancaster . [Henry VI Part 2] Anon. 1595 The true tragedie of Richard Duke of York , and P. S. [Peter Short] Thomas Millington bad 1600 the death of good King Henrie the Sixt, with the whole contention betweene the two houses Lancaster and Yorke, as it was sundrie times acted by the Right Honourable the Earle of Pembrooke his seruants [Henry VI Part 3] Anon. 1597 An excellent conceited tragedie of Romeo and Iuliet. Iohn Danter [and bad As it hath been often (with great applause) plaid Edward Allde] publiquely, by the Right Honourable the L. of Hunsdon his seruants Anon. 29 August 1597 to Andrew 1597 The tragedie of King Richard the second. As it hath Valentine Simmes Andrew Wise "rather good" Wise been publikely acted by the Right Honourable the Lorde Chamberlaine his seruants. William Shake-speare [29 Aug 1597] 1598 The tragedie of King Richard the second. -

Authorial Rights, Part II

AUT H O R I A L RIG H T S, PAR T II Early Shakespeare Critics and the Authorship Question Robert Detobel ❦ It had been a thing, we confess, worthy to have been wished, that the author himself had lived to have set forth and overseen his own writings, but since it hath been ordained otherwise and he by death departed from that right, we pray you do not envy his friends the office of their care and pain to have collected and published them, and so to have published them, as where (before) you were abused with diverse stolen and surrepti- tious copies, maimed and deformed by the frauds and stealths of injurious imposters that exposed them, even those are now offered to your view, cured and perfect of their limbs and all the rest absolute in their numbers, as he conceived them. John Heminge and Henry Condell From the preface to the First Folio, 1623 ULY 22, 1598 , the printer, James Roberts, entered The Merchant of Venice in the Stationers’ Register as follows: Iames Robertes Entred for his copie under the handes of bothe the wardens, a booke of the Marchaunt of Venyce or otherwise called the Iewe of Venyce./ Provided that yt bee not printed by the said Iames Robertes; or anye other whatsoever without lycence first had from the Right honorable the lord Chamberlen. Orthodox scholarship can offer no satisfactory explanation for the final clause, which states that the play could not be printed by Roberts, the legal holder of the copyright, nor by any other stationer, without the permission of the Lord Chamberlain. -

Article Reference

Article Shakespeare and the Publication of His Plays ERNE, Lukas Christian Abstract Challenging the accepted view that Shakespeare was indifferent to the publication of his plays by focusing on the economics of the booktrade, examines the evidence that the playing companies resisted publishing their plays, reviews "the publication history of Shakespeare's plays, which suggests that the Lord Chamberlain's Men has a coherent strategy to try to get their playwright's plays into print," and "inquire[s] into what can or cannot be inferred from Shakespeare's alleged involvement (as with the narrative poems) or noninvolvement (as with the plays) in the publication of his writings." Concluding that publishers had little economic incentive to publish drama, calls for renewed attention to Shakespeare's attitude to his plays and their publication. Reference ERNE, Lukas Christian. Shakespeare and the Publication of His Plays. Shakespeare Quarterly, 2002, vol. 53, p. 1-20 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:14491 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 Shakespeare and the Publication of His Plays LUKAS ERNE N WHAT S. SCHOENBAUM HAS CALLED Pope's "most influential contribution to IShakespearian biography;' the eighteenth-century poet and critic wrote: Shakespear, (whom you and ev'ry Play-house bill Style the divine, the matchless, what you will) For gain, not glory, wing'd his roving flight, And grew Immortal in his own despight. 1 Pope's lines were no doubt instrumental in reinforcing the opinion, soon to be frozen into dogma, that Shakespeare cared only for that form of publication—the stage which promised an immediate payoff, while being indifferent to the one that even- tually guaranteed his immortality—the printed page. -

04 Woudhuysen 1226 7/12/04 12:01 Pm Page 69

04 Woudhuysen 1226 7/12/04 12:01 pm Page 69 SHAKESPEARE LECTURE The Foundations of Shakespeare’s Text H. R. WOUDHUYSEN University College London EIGHTY YEARS AGO TODAY my great-grandfather, Alfred W. Pollard, delivered this Annual Shakespeare Lecture on ‘The Foundations of Shakespeare’s Text’, the lecture coinciding with the tercentenary of the publication of the First Folio. To compare great things to small, this year all we can celebrate is the quatercentenary of the first quarto of Hamlet— a so-called ‘bad’ quarto. Surveying current knowledge about the quarto and Folio editions of Shakespeare’s plays, Pollard argued that, compared to the fate of Dr Faustus (‘a few fine speeches overladen with much alien buffoonery’) or the texts of the plays of Greene and Peele (‘scanty and mangled’), Shakespeare’s plays ‘have come down to us in so much better condition’, the texts presenting ‘to the sympathetic reader, and still more to the sympathetic listener . very few obstacles’. No wonder he called himself ‘an incurable optimist’—a characteristic I have not fully inherited from him.1 That general optimism about the state of Shakespeare’s texts was largely shared by Pollard’s friends and followers R. B. McKerrow and W. W. Greg, the proponents of what became known as the ‘New Bibliography’. The three of them elaborated an essential model of textual transmission, involving two sorts of lost manuscript—autograph drafts (called in con- temporary documents ‘foul papers’) and the theatrical ‘promptbook’— and two types of quarto. There were ‘bad’ quartos, containing shorter, Read at the Academy 23 April 2003. -

View Fast Facts

FAST FACTS Author's Works and Themes: Hamlet “Author's Works and Themes: Hamlet.” Gale, 2019, www.gale.com. Writings by William Shakespeare Play Productions • Henry VI, part 1, London, unknown theater (perhaps by a branch of the Queen's Men), circa 1589-1592. • Henry VI, part 2, London, unknown theater (perhaps by a branch of the Queen's Men), circa 1590-1592. • Henry VI, part 3, London, unknown theater (perhaps by a branch of the Queen's Men), circa 1590-1592. • Richard III, London, unknown theater (perhaps by a branch of the Queen's Men), circa 1591-1592. • The Comedy of Errors, London, unknown theater (probably by Lord Strange's Men), circa 1592-1594; London, Gray's Inn, 28 December 1594. • Titus Andronicus, London, Rose or Newington Butts theater, 24 January 1594. • The Taming of the Shrew, London, Newington Butts theater, 11 June 1594. • The Two Gentlemen of Verona, London, Newington Butts theater or the Theatre, 1594. • Love's Labor's Lost, perhaps at the country house of a great lord, such as the Earl of Southampton, circa 1594-1595; London, at Court, Christmas 1597. • Sir Thomas More, probably by Anthony Munday, revised by Thomas Dekker, Henry Chettle, Shakespeare, and possibly Thomas Heywood, evidently never produced, circa 1594-1595. • King John, London, the Theatre, circa 1594-1596. • Richard II, London, the Theatre, circa 1595. • Romeo and Juliet, London, the Theatre, circa 1595-1596. • A Midsummer Night's Dream, London, the Theatre, circa 1595-1596. • The Merchant of Venice, London, the Theatre, circa 1596-1597. • Henry IV, part 1, London, the Theatre, circa 1596-1597. -

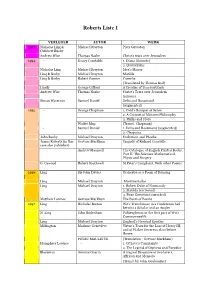

Roberts Liste 1

Roberts Liste 1 VERLEGER AUTOR WERK 1593 Nicholas Ling & Michael Drayton Piers Gaveston Cuthbert Busby Andrew Wise Thomas Nashe Christ’s tears over Jerusalem 1594 - Henry Constable 1. Diana (Sonnets) 2. Quatorzains Nicholas Ling Michael Drayton Idea’s Mirror Ling & Busby Michael Drayton Matilda Ling & Busby Robert Garnier Cornelia (Translated by Thomas Kyd) Hardy George Gifford A Treatise of True Fortitude Andrew Wise Thomas Nashe Christ’s Tears over Jerusalem (reissue) Simon Waterson Samuel Daniel Delia and Rosamond (augmented) 1595 - George Chapman 1. Ovid’s Banquet of Sense 2. A Coronet of Mistress Philosophy 3. Phillis and Flora Walter Map. (Transl. Chapman) - Samuel Daniel 1. Delia and Rosamond (augmented) 2. Cleopatra John Busby Michael Drayton Endymion and Phoebe James Roberts (in this Gervase Markham Tragedy of Richard Grenville case also publisher) Andrew Maunsell The Catalogue of English Printed Books, Part II. The Sciences Mathematical, Physic and Surgery G. Cawood Robert Southwell St Peter’s Complaint. With other Poems 1596 Ling Sir John Davies Orchestra or a Poem of Dancing Ling Michael Drayton Mortimeriados Ling Michael Drayton 1. Robert Duke of Normandy 2. Matilda (corrected) 3. Piers Gaveston (corrected) Matthew Lownes Gervase Markham The Poem of Poems 1597 Ling Nicholas Breton Wit’s Trenchmour in a Conference had betwixt a Scholar and an Angler N. Ling John Bodenham Politeupheuia or the first part of Wit’s Commonwealth Ling Michael Drayton England’s Heroical Epistles Millington Madame Geneviève Virtue’s Tears for the Loss of Henry III; and of Walter Devereux slain before Rouen PETAU MAULETTE (Translation : Gervase Markham) Humphrey Lownes - 1. -

Cuthbert Burby, 1599

A rare early quarto edition of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet. London: Cuthbert Burby, 1599. 7 1/16 inches x 4 13/16 inches (179 mm x 123 mm), [92] pages, A–L4 M2. The | most ex= | cellent and lamentable | Tragedie, of Romeo | and Iuliet. | Newly corrected, augmented, and | amended: As it hath bene sundry times publiquely acted, by the | right Honourable the Lord Chamberlaine | his Seruants. | [Creede’s device] | London | Printed by Thomas Creede, for Cuthbert Burby, and are to | be sold at his shop neare the Exchange. | 1599. Shakespeare’s quartos, so named because of their format (a single sheet folded twice, creating four leaves or eight pages), are the first printed representations of his plays and, as none of the plays survives in manuscript, of great importance to Shakespeare scholarship. Only twenty-one of Shakespeare’s plays were published in quarto before the closure of the theaters and outbreak of civil war in 1642. These quartos were printed from either Shakespeare’s “foul papers” (a draft with notations and changes that was given in sections to actors for their respective roles); from “fair copies” created from foul papers that presented the entire action of the play; from promptbooks, essentially fair copies annotated and expanded by the author and acting company to clarify stage directions, sound effects, etc.; or from a previously published quarto edition. The quartos were inexpensive to produce and were published for various reasons, including to secure the acting company’s rights to the material and to bring in money during the plague years in London when the theaters were closed. -

A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare: 1599

A Year in the Life of WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE 1599 JAMES SHAPIRO For Mary and Luke CONTENTS Preface Prologue – WINTER – 1. A Battle of Wills 2. A Great Blow in Ireland 3. Burial at Westminster 4. A Sermon at Richmond 5. Band of Brothers – SPRING – 6. The Globe Rises 7. Book Burning 8. Is This a Holiday? – SUMMER – 9. The Invisible Armada 10. The Passionate Pilgrim 11. Simple Truth Suppressed 12. The Forest of Arden – AUTUMN – 13. Things Dying, Things Newborn 14. Essays and Soliloquies 15. Second Thoughts Epilogue Bibliographical Essay Acknowledgments Searchable Terms About the Author Also by James Shapiro Credits Copyright About the Publisher PREFACE In 1599, Elizabethans sent off an army to crush an Irish rebellion, weathered an armada threat from Spain, gambled on a fledgling East India Company, and waited to see who would succeed their aging and childless queen. They also flocked to London’s playhouses, including the newly built Globe. It was at the theater, noted Thomas Platter, a Swiss tourist who visited England and saw plays there in 1599, that “the English pass their time, learning at the play what is happening abroad.” England’s dramatists did not disappoint, especially Shakespeare, part owner of the Globe, whose writing this year rose to a new and extraordinary level. In the course of 1599 Shakespeare completed Henry the Fifth, wrote Julius Caesar and As You Like It in quick succession, then drafted Hamlet. This book is both about what Shakespeare achieved and what Elizabethans experienced this year. The two are nearly inextricable: it’s no more possible to talk about Shakespeare’s plays independent of his age than it is to grasp what his society went through without the benefit of Shakespeare’s insights. -

Rebecca Hasler, '“Tossing and Turning Your Booke Upside Downe”

This is the accepted version of the following article: Rebecca Hasler, ‘“Tossing and turning your booke upside downe”: The Trimming of Thomas Nashe, Cambridge, and Scholarly Reading’, Renaissance Studies, DOI 10.1111/rest.12504, Copyright © 2018, Wiley. The article has been published in final form at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/14774658. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with the wiley self- archiving policy [https://authorservices.wiley.com/author-resources/journal- authors/licensing-open-access/open-access/self-archiving.html]. 1 ‘TOSSING AND TURNING YOUR BOOKE UPSIDE DOWNE’: THE TRIMMING OF THOMAS NASHE, CAMBRIDGE, AND SCHOLARLY READING REBECCA HASLER The 1597 pamphlet The Trimming of Thomas Nashe launches a powerful attack on Thomas Nashe’s style and persona. Presenting himself as ‘tossing and turning [Nashe’s] booke upside downe’, the pamphlet’s author draws upon his close reading of Nashe’s Have With You to Saffron-Walden (1596).1 Throughout The Trimming, the physical processes of reading — the ‘tossing and turning’ of pages — are aligned with a skilful critical analysis that deconstructs Nashe’s text in order to condemn and parody it. The central discursive function of reading in The Trimming is linked to the pamphlet’s Cambridge origins. As this article will demonstrate, The Trimming was published by a Cambridge bookseller for an audience of Cambridge scholars. Within this scholarly community, there was a fashion for critical reading; throughout the Harvey-Nashe Quarrel, and in dramatic works like the Parnassus plays, Cambridge scholars used close reading as a means of expressing their superiority to London’s professional theatres and print market.