Detection of New Emission Structures Around Planetary Nebulae?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planetary Nebulae

Planetary Nebulae A planetary nebula is a kind of emission nebula consisting of an expanding, glowing shell of ionized gas ejected from old red giant stars late in their lives. The term "planetary nebula" is a misnomer that originated in the 1780s with astronomer William Herschel because when viewed through his telescope, these objects appeared to him to resemble the rounded shapes of planets. Herschel's name for these objects was popularly adopted and has not been changed. They are a relatively short-lived phenomenon, lasting a few tens of thousands of years, compared to a typical stellar lifetime of several billion years. The mechanism for formation of most planetary nebulae is thought to be the following: at the end of the star's life, during the red giant phase, the outer layers of the star are expelled by strong stellar winds. Eventually, after most of the red giant's atmosphere is dissipated, the exposed hot, luminous core emits ultraviolet radiation to ionize the ejected outer layers of the star. Absorbed ultraviolet light energizes the shell of nebulous gas around the central star, appearing as a bright colored planetary nebula at several discrete visible wavelengths. Planetary nebulae may play a crucial role in the chemical evolution of the Milky Way, returning material to the interstellar medium from stars where elements, the products of nucleosynthesis (such as carbon, nitrogen, oxygen and neon), have been created. Planetary nebulae are also observed in more distant galaxies, yielding useful information about their chemical abundances. In recent years, Hubble Space Telescope images have revealed many planetary nebulae to have extremely complex and varied morphologies. -

SEPTEMBER 2014 OT H E D Ebn V E R S E R V ESEPTEMBERR 2014

THE DENVER OBSERVER SEPTEMBER 2014 OT h e D eBn v e r S E R V ESEPTEMBERR 2014 FROM THE INSIDE LOOKING OUT Calendar Taken on July 25th in San Luis State Park near the Great Sand Dunes in Colorado, Jeff made this image of the Milky Way during an overnight camping stop on the way to Santa Fe, NM. It was taken with a Canon 2............................. First quarter moon 60D camera, an EFS 15-85 lens, using an iOptron SkyTracker. It is a single frame, with no stacking or dark/ 8.......................................... Full moon bias frames, at ISO 1600 for two minutes. Visible in this south-facing photograph is Sagittarius, and the 14............ Aldebaran 1.4˚ south of moon Dark Horse Nebula inside of the Milky Way. He processed the image in Adobe Lightroom. Image © Jeff Tropeano 15............................ Last quarter moon 22........................... Autumnal Equinox 24........................................ New moon Inside the Observer SEPTEMBER SKIES by Dennis Cochran ygnus the Swan dives onto center stage this other famous deep-sky object is the Veil Nebula, President’s Message....................... 2 C month, almost overhead. Leading the descent also known as the Cygnus Loop, a supernova rem- is the nose of the swan, the star known as nant so large that its separate arcs were known Society Directory.......................... 2 Albireo, a beautiful multi-colored double. One and named before it was found to be one wide Schedule of Events......................... 2 wonders if Albireo has any planets from which to wisp that came out of a single star. The Veil is see the pair up-close. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

Catalogue of Excitation Classes P for 750 Galactic Planetary Nebulae

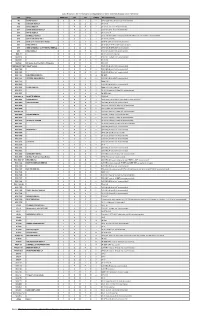

Catalogue of Excitation Classes p for 750 Galactic Planetary Nebulae Name p Name p Name p Name p NeC 40 1 Nee 6072 9 NeC 6881 10 IC 4663 11 NeC 246 12+ Nee 6153 3 NeC 6884 7 IC 4673 10 NeC 650-1 10 Nee 6210 4 NeC 6886 9 IC 4699 9 NeC 1360 12 Nee 6302 10 Nee 6891 4 IC 4732 5 NeC 1501 10 Nee 6309 10 NeC 6894 10 IC 4776 2 NeC 1514 8 NeC 6326 9 Nee 6905 11 IC 4846 3 NeC 1535 8 Nee 6337 11 Nee 7008 11 IC 4997 8 NeC 2022 12 Nee 6369 4 NeC 7009 7 IC 5117 6 NeC 2242 12+ NeC 6439 8 NeC 7026 9 IC 5148-50 6 NeC 2346 9 NeC 6445 10 Nee 7027 11 IC 5217 6 NeC 2371-2 12 Nee 6537 11 Nee 7048 11 Al 1 NeC 2392 10 NeC 6543 5 Nee 7094 12 A2 10 NeC 2438 10 NeC 6563 8 NeC 7139 9 A4 10 NeC 2440 10 NeC 6565 7 NeC 7293 7 A 12 4 NeC 2452 10 NeC 6567 4 Nee 7354 10 A 15 12+ NeC 2610 12 NeC 6572 7 NeC 7662 10 A 20 12+ NeC 2792 11 NeC 6578 2 Ie 289 12 A 21 1 NeC 2818 11 NeC 6620 8 IC 351 10 A 23 4 NeC 2867 9 NeC 6629 5 Ie 418 1 A 24 1 NeC 2899 10 Nee 6644 7 IC 972 10 A 30 12+ NeC 3132 9 NeC 6720 10 IC 1295 10 A 33 11 NeC 3195 9 NeC 6741 9 IC 1297 9 A 35 1 NeC 3211 10 NeC 6751 9 Ie 1454 10 A 36 12+ NeC 3242 9 Nee 6765 10 IC1747 9 A 40 2 NeC 3587 8 NeC 6772 9 IC 2003 10 A 41 1 NeC 3699 9 NeC 6778 9 IC 2149 2 A 43 2 NeC 3918 9 NeC 6781 8 IC 2165 10 A 46 2 NeC 4071 11 NeC 6790 4 IC 2448 9 A 49 4 NeC 4361 12+ NeC 6803 5 IC 2501 3 A 50 10 NeC 5189 10 NeC 6804 12 IC 2553 8 A 51 12 NeC 5307 9 NeC 6807 4 IC 2621 9 A 54 12 NeC 5315 2 NeC 6818 10 Ie 3568 3 A 55 4 NeC 5873 10 NeC 6826 11 Ie 4191 6 A 57 3 NeC 5882 6 NeC 6833 2 Ie 4406 4 A 60 2 NeC 5879 12 NeC 6842 2 IC 4593 6 A -

Planetary Nebulas

The History, Observation, and Science of Planetary Nebulas Plus: Mars Exploration Update (at end) Tuesday, February 5, 2013 What is a “Planetary” Nebula? Dark Nebula: We see it because of light it blocks. Emission Nebula: The cloud itself glows. Planetary Nebula Galaxies were once classed as nebulas, too. Supernova Remnant: Reflection Nebula: What’s left after a star goes “boom” Reflects light from a star. “nebula” is latin for mist, fog, or cloud. Tuesday, February 5, 2013 Origin of the Term ‘Planetary Nebula’ William Herschel: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 1785, Volume 75, Page 263 ff*: Planetary Nebulae “I shall conclude this paper with an account of a few heavenly bodies, that from their singular appearance leave me almost in doubt where to class them...being all over of an uniform brightness, which it differs from nebulae, it light seems however to be of the starry nature, which suffers not so much as the planetary disks are know to do, when much magnified. The planetary appearance of the first two is so remarkable that we can hardly suppose them to be nebulae; their light is so uniform, as well as vivid, the diameters so small and well defined as to make it almost improbable that they should belong to that species of bodies. On the other hand, the effect of different power seems to be much against their light’s being of a planetary nature, since it preserves its brightness nearly in the same manner as to the stars in similar trials.” He describes five planetaries (Six listed, 5 and 6 appear to be repeats): NGC 7293 (Helix), NGC 7662 (Blue Snowball), NGC 6369 (Little Ghost), NGC 6853 (Dumbbell), NGC 6894 (Diamond Ring) He makes two guesses in 1785 about what they are: Star clusters that can’t be resolved, or Dead or dying stars, possibly multiple stars falling into each other. -

September 2017

the vol. 44 no. 09 Skyscraper September 2017 AMATEUR ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY OF RHODE ISLAND 47 PEEPTOAD ROAD NORTH SCITUATE, RHODE ISLAND 02857 WWW.THESKYSCRAPERS.ORG In This Issue: Friday, September 8 2 Astronomy Nights at River Bend Farm at Seagrave Observatory 2 Cosmic Colors at the Special Report: Eclipse Day at Seagrave Observatory University of Rhode In addition, anyone interested in pre- Our guidelines for the 10 minute presen- Island Planetarium senting at this meeting must contact Ian tations will be emailed to you if you show Dell'Antonio (ian_dellantonio@brown. interest. 3 The Sun, Moon & edu) by Wednesday, September 6th by If you would like to bring some snacks, Planets in August email. Please include your name, where you please contact Kathy Siok (kathys5@cox. viewed the eclipse and any other informa- net) by Wednesday September 6th. Water 4 September Stargazing tion you wish. Last minute presentations and coffee will be provided. 5 A Farewell to Cassini may not be possible, so please plan ahead. 6 Planetary Nebula in Delphinus NGC 6905 7 August Reports 7 Solar Eclipse Reports & Gallery 13 AstroAssembly Information & Registration Skyscrapers Board Meetings Third Monday of the Month All Members Welcome Phases of the Moon Full Corn Moon September 6 07:03 Last Quarter Moon Seagrave Memorial September 13 06:25 Observatory New Moon September 20 05:30 Open Nights First Quarter Moon Saturdays st 8:00 pm September 28 02:54 weather permitting Astronomy Nights at River Bend Farm Joshua Bell is one of the rangers at Black- If we have poor weather an email will be weather, we'll just have to wait until the fol- stone River Valley National Historical Park sent out that day to let you know that the lowing month. -

Dave Knisely's Filter Performance Comparisons for Some Common Nebulae Quick Reference

Dave Knisely's Filter Performance Comparisons For Some Common Nebulae Quick Reference Ref Name DEEP-SKY UHC OIII H-BETA Recommendation M1 CRAB NEBULA 3 4 3 0 UHC/DEEP-SKY (H-beta *not* recommended) M8 LAGOON NEBULA 3 5 5 2 UHC/OIII M16 EAGLE NEBULA 2 4 4 2 UHC/OIII, but H-BETA hurts the view M17 SWAN (OMEGA) NEBULA 3 4 5 1 OIII/UHC (H-BETA not recommended) M20 TRIFID NEBULA 2 4 3 4 UHC/H-BETA M27 DUMBELL NEBULA 3 5 4 1 UHC (OIII also useful in showing some inner detail, but H-BETA is NOT recommended) M42 GREAT ORION NEBULA 3 5 4 3 UHC/OIII (near-tie) M43 North part of Great Orion Nebula 3 3 2 4 H-BETA (UHC and Deep-Sky also help) M57 RING NEBULA 2 4 4 0 UHC/OIII (H-BETA is NOT recommended!) M76 “MINI-DUMBELL” or BUTTERFLY NEBULA 2 4 3 0 UHC/OIII (H-BETA NOT recommended!) M97 OWL NEBULA 2 4 5 0 OIII/UHC (H-beta *not* recommended) NGC 40 3 3 2 2 DEEP-SKY/UHC (near tie) NGC 246 2 3 4 0 OIII/UHC. (H-Beta *not* recommended) NGC 281 3 4 4 2 UHC/OIII. NGC 604 HII region in galaxy M33 in Triangulum 2 3 4 2 OIII/UHC NGC 896/IC 1795 “Heart” nebula 3 4 4 1 UHC/OIII (H-beta *not* recommended) NGC 1360 2 4 4 0 OIII/UHC (H-beta *not* recommended) NGC 1491 3 5 4 0 UHC/OIII (H-Beta *not* recommended) NGC 1499 CALIFORNIA NEBULA 2 2 1 4 H-BETA NGC 1514 CRYSTAL-BALL NEBULA 2 4 4 0 OIII/UHC (H-Beta NOT recommended) NGC 1999 2 1 1 1 DEEP-SKY NGC 2022 3 4 5 0 OIII/UHC (H-Beta NOT recommended) NGC 2024 FLAME NEBULA 3 3 2 1 DEEP-SKY/UHC (near tie) NGC 2174 2 4 4 0 UHC/OIII (near tie) (H-Beta NOT recommended) NGC 2327 2 3 2 4 H-BETA/UHC NGC 2237-9 ROSETTE NEBULA 2 5 5 1 UHC/OIII NGC 2264 CONE NEBULA 2 3 2 1 UHC (other filters may be more useful in larger apertures) NGC 2359 THOR’S HELMET 2 4 5 0 OIII/UHC (H-Beta *not* recommended) NGC 2346 2 3 3 0 UHC/OIII (near tie) (H-beta *not* recommended) NGC 2438 2 3 4 0 OIII (H-Beta *not* recommended) NGC 2371-2 2 4 4 0 OIII/UHC (near tie) (H-Beta *not* recommended) NGC 2392 ESKIMO NEBULA 2 4 4 0 OIII/UHC. -

The Prairie Astronomer the Official Newsletter of the Prairie Astronomy Club

August, 2013 Volume 54, Issue #8 The Prairie Astronomer The Official Newsletter of the Prairie Astronomy Club August Program IN THIS Nebraska Star Party Report and Photos ISSUE: What to View in September NGC Objects Nebraska Star Party Featured Photo By Brett Boller: 5 Minute shot of the Sagittarius arm of the Milky Way. Taken at NSP, Merritt Reservoir. MSRAL The Prairie Astronomer is published monthly by the Prairie Astronomy Club, Inc. Membership expiration date is listed on the mailing label. Membership dues are: Regular $30/yr, Family $35/yr. Address all new memberships and renewals to: The Prairie Astronomy Club, Inc., PO Box 5585, Lincoln, NE 68505-0585. For other club information, please contact one of the club officers listed to the right. Newsletter comments and articles should be submitted to: Mark Dahmke, P. O. Box 5585, Lincoln, NE 68505 or [email protected], no less than ten days prior to the club meeting. The Prairie Astronomy Club meets the last Tuesday of each month at Hyde Memorial Observatory in Lincoln, NE. Meeting Minutes Jason Noelle called meeting to order at 7:30 PM Tuesday July 30, 2013. No official other business. Some informal conversation about Nebraska Star Party prizes. Last meeting was the annual BBQ and social. No business meeting was held in June. Observing report was presented by Jim Kvasnicka. 3 dates in June. June 28 (9 Next meeting is August 27th with Nebraska Star attended), July 5 (1 attendee), July 12 (6 Party (NSP) recap and slideshow. attended). Next star parties August 2 and August 9, concurrent with Nebraska Star Party. -

Popular Names of Deep Sky (Galaxies,Nebulae and Clusters) Viciana’S List

POPULAR NAMES OF DEEP SKY (GALAXIES,NEBULAE AND CLUSTERS) VICIANA’S LIST 2ª version August 2014 There isn’t any astronomical guide or star chart without a list of popular names of deep sky objects. Given the huge amount of celestial bodies labeled only with a number, the popular names given to them serve as a friendly anchor in a broad and complicated science such as Astronomy The origin of these names is varied. Some of them come from mythology (Pleiades); others from their discoverer; some describe their shape or singularities; (for instance, a rotten egg, because of its odor); and others belong to a constellation (Great Orion Nebula); etc. The real popular names of celestial bodies are those that for some special characteristic, have been inspired by the imagination of astronomers and amateurs. The most complete list is proposed by SEDS (Students for the Exploration and Development of Space). Other sources that have been used to produce this illustrated dictionary are AstroSurf, Wikipedia, Astronomy Picture of the Day, Skymap computer program, Cartes du ciel and a large bibliography of THE NAMES OF THE UNIVERSE. If you know other name of popular deep sky objects and you think it is important to include them in the popular names’ list, please send it to [email protected] with at least three references from different websites. If you have a good photo of some of the deep sky objects, please send it with standard technical specifications and an optional comment. It will be published in the names of the Universe blog. It could also be included in the ILLUSTRATED DICTIONARY OF POPULAR NAMES OF DEEP SKY. -

A Search for Cool Companions of Planetary Nebula Nuclei

A SEARCH FOR COOL COMPANIONS OF PLANETARY NEBULA NUCLEI A. F. Bentley Department of Physical Sciences Eastern Montana College Billings, Montana 59101 At present only a small number of planetary nebulae are known to possess binary nuclei. Since approximately 2/3 of main sequence stars are mem- bers of binary or multiple star systems, one might expect a large frac- tion of PN central stars to have gravitationally bound companions. Ad- ditionally, late-type stars are more numerous, and due to their low lu- minosities would be difficult to detect by visual observational methods at distances where PN are typically found (^1 kpc). (Only 5 known PN are thought to be nearer than 0.5 kpc). It is thus possible, and in our view probable, that a significant number of PN nuclei possess cool com- panions, hitherto undetected. Since Κ and M stars emit a considerable fraction of their energy in the infrared, we calculated the feasibility of detecting them with the Wyoming InSb photometer, and found that such detections might be possi- ble out to distances of ^2 kpc. To date 13 objects have been observed, including a sample of planetaries with known binary nuclei to test our hypothesis. The results are listed below. Object IR Excess Remark Object IR Excess Remark NGC 7293 no NGC 6905 no NGC 6853 no detection NGC 6543 yes known binary NGC 246 yes known binary NGC 6572 yes known binary NGC 7008 ? NGC 6790 yes NGC 40 ? NGC 6210 yes new binary? NGC 6826 yes new binary ? A 63 yes known binary NGC 7009 yes new binary ? The observations were made using standard infrared techniques in the J, H, K, and L bands. -

Angular Dimensions of Planetary Nebulae?

A&A 405, 627–637 (2003) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20030645 & c ESO 2003 Astrophysics Angular dimensions of planetary nebulae? R. Tylenda1,N.Si´odmiak1,S.K.G´orny1,R.L.M.Corradi2, and H. E. Schwarz3 1 N. Copernicus Astronomical Center, Department for Astrophysics, Rabia´nska 8, 87–100 Toru´n, Poland 2 Isaac Newton Group of Telescopes, Apartado de Correos 321, 38700 Sta. Cruz de La Palma, Spain 3 CTIO/NOAO, Casilla 603, La Serena, Chile Received 28 May 2002 / Accepted 23 April 2003 Abstract. We have measured angular dimensions of 312 planetary nebulae from their images obtained in Hα (or Hα + [NII]). We have applied three methods of measurements: direct measurements at the 10% level of the peak surface brightness, Gaussian deconvolution and second-moment deconvolution. The results from the three methods are compared and analysed. We propose a simple deconvolution of the 10% level measurements which significantly improves the reliability of these measurements for compact and partially resolved nebulae. Gaussian deconvolution gives consistent but somewhat underestimated diameters compared to the 10% measurements. Second-moment deconvolution gives results in poor agreement with those from the other two methods, especially for poorly resolved nebulae. From the results of measurements and using the conclusions of our analysis we derive the final nebular diameters which should be free from systematic differences between small (partially resolved) and extended (well resolved) objects in our sample. Key words. planetary nebulae: general 1. Introduction different results for many PNe. In the case of well resolved and fairly symmetric nebulae with a well defined outer rim the The angular dimensions belong to the most fundamental obser- problem is simple and different methods give consistent results. -

100 Brightest Planetary Nebulae

100 BRIGHTEST PLANETARY NEBULAE 100 BRIGHTEST PLANETARY NEBULAE 1 100 BRIGHTEST PLANETARY NEBULAE Visual Magnitude (brightest to least bright) Name Common Name Visual Magnitude Stellar Magnitude Angular Size Constellation NGC 7293 Helix Nebula 7 13.5 900 Aquarius NGC 6853 Dumbbell Nebula (M27) 7.5 13.9 330 Vulpecula NGC 3918 Blue Planetary 8 ? 16 Centaurus NGC 7009 Saturn Nebula 8 12.8 28 Aquarius NGC 3132 Eight‐Burst Planetary 8.5 10.1 45 Vela NGC 6543 Cat's Eye Nebula 8.5 11.1 20 Draco NGC 246 Skull Nebula 8.5 12 225 Cetus NGC 6572 Blue Raquetball Nebula 8.5 13.6 14 Ophiuchus NGC 6210 Turtle Nebula 9 12.7 16 Hercules NGC 6720 Ring Nebula (M57) 9 15.3 70 Lyra NGC 7027 Magic Carpet Nebula 9 16.3 14 Cygnus NGC 7662 Blue Snowball Nebula 9 13.2 20 Andromeda NGC 1360 Robin's Egg Nebula 9.5 11.4 380 Fornax NGC 1535 Cleopatra's Eye Nebula 9.5 12.2 18 Eridanus NGC 2392 Eskimo/Clown Face Nebula 9.5 10.5 45 Gemini NGC 2867 Royal Aqua Nebula 9.5 16.6 15 Carina NGC 3242 Ghost of Jupiter Nebula 9.5 12.3 40 Hydra NGC 6826 Blinking Planetary Nebula 9.5 10.4 25 Cygnus IC 418 Spirograph Nebula 10 10.2 12 Lepus NGC 5189 Spiral Planetary Nebula 10 14.9 140 Musca NGC 5882 Green Snowball Nebula 10 13.4 14 Lupus NGC 6818 Little Gem Nebula 10 16.9 18 Sagittarius NGC 40 Bow Tie Nebula 10.5 11.6 36 Cepheus NGC 1514 Crystal Ball Nebula 10.5 9.4 120 Taurus NGC 2346 Butterfly Nebula 10.5 11.5 55 Monoceros NGC 2438 Smoke Ring in M46 10.5 17.7 70 Puppis NGC 2440 Peanut Nebula 10.5 17.7 30 Puppis NGC 4361 Raven's Eye Nebula 10.5 13.2 100 Corvus IC 4406 Retina Nebula