Michael Winer, Cape York Institute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT Contents AIEF Annual Report 2009 1 Messages from our Patrons 2 2 Chairman’s Overview – Ray Martin AM 4 3 Chief Executive’s Report – Andrew Penfold 6 4 AIEF Scholarship Programme 8 5 AIEF 2009 Partner Schools: Kincoppal – Rose Bay School 12 Presbyterian Ladies’ College, Sydney 14 St Catherine’s School, Waverley 16 St Scholastica’s College, Glebe 18 St Vincent’s College, Potts Point 20 Other Partnerships and Scholarships 22 6 Student Overviews – Current and Past Students at 2009 Partner Schools 24 7 Financial Summary 34 APPENDIX A Governance and People 38 B Contact and Donation Details 40 1 Messages from our Patrons Her Excellency Professor Marie Bashir AC CVO Governor of New South Wales Patron-in-Chief It is an honour to be the Patron-in-Chief of the Australian Indigenous Education Foundation and to be able to follow the growth and development of the organisation over the past 12 months in its resolve and drive to create opportunities for a quality education for more Indigenous children across the nation. AIEF is an excellent example of how individuals and corporate organisations can make a difference to the lives of Indigenous children by facilitating access to educational opportunities that would not otherwise be available to them, and to do so in an efficient framework that provides clear, transparent and regular reporting. This initiative also benefits non-Indigenous children in our schools by providing the opportunity for our non-Indigenous students to form bonds of friendship with, and cultural understanding of, their Indigenous classmates. In this way, we are together working towards a brighter future for all Australians and empowering Indigenous children to have real choices in life. -

The Task Cards

HEROES HEROES TASK CARD 1 TASK CARD 2 HERO RECEIVES PURPLE CROSS YOUNG AUSTRALIAN OF THE YEAR The Young Australian of the Year has been awarded since 1979. It Read the story about Sarbi and answer these questions. recognises the outstanding achievement of young Australians aged 16 to 30 and the contributions they have made to our communities. 1. What colour is associated with the Australian Special Forces? YEAR Name of Recipient Field of Achievement 2011 Jessica Watson 2. What breed of dog is Sarbi? 2010 Trooper Mark Donaldson VC 2009 Jonty Bush 3. What is Sarbi trained to do? 2008 Casey Stoner 2007 Tania Major 4. What type of animal has also received 2006 Trisha Broadbridge the Purple Cross for wartime service? 2005 Khoa Do 2004 Hugh Evans 5. In which country was Sarbi working 2003 Lleyton Hewitt when she went missing? 2002 Scott Hocknull 2001 James Fitzpatrick 6. How was Sarbi identified when she was found? 2000 Ian Thorpe OAM 1999 Dr Bryan Gaensler 7. What does MIA stand for? 1998 Tan Le 1997 Nova Peris OAM 8. Which word in the text means ‘to attack by surprise’? 1996 Rebecca Chambers 1995 Poppy King 9. How many days was Sarbi missing for? Find out what each of these people received their Young Australian 10. Why did Sarbi receive the Purple cross? Award for. Use this list of achievements to help you. Concert pianist; Astronomer; Champion Tennis Player; Sailor; Palaeontologist; MotoGP World Champion; Business Woman; World Champion Swimmer; Youth Leader & Tsunami Survivor; Anti-poverty Campaigner; Olympic Gold Medallist Athlete; Victim -

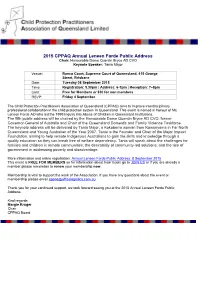

2015 CPPAQ Annual Leneen Forde Public Address Chair: Honourable Dame Quentin Bryce AD CVO Keynote Speaker: Tania Major

2015 CPPAQ Annual Leneen Forde Public Address Chair: Honourable Dame Quentin Bryce AD CVO Keynote Speaker: Tania Major Venue: Banco Court, Supreme Court of Queensland, 415 George Street, Brisbane Date: Tuesday 08 September 2015 Time: Registration: 5.30pm | Address: 6-7pm | Reception: 7–8pm Cost: Free for Members or $30 for non members RSVP: Friday 4 September The Child Protection Practitioners Association of Queensland (CPPAQ) aims to improve interdisciplinary professional collaboration in the child protection system in Queensland. This event is named in honour of Ms Leneen Forde AO who led the 1999 Inquiry into Abuse of Children in Queensland Institutions. The fifth public address will be chaired by the Honourable Dame Quentin Bryce AD CVO, former Governor-General of Australia and Chair of the Queensland Domestic and Family Violence Taskforce. The keynote address will be delivered by Tania Major, a Kokoberra woman from Kowanyama in Far North Queensland and Young Australian of the Year 2007. Tania is the Founder and Chair of the Major Impact Foundation, aiming to help remote Indigenous Australians to gain the skills and knowledge through a quality education so they can break free of welfare dependency. Tania will speak about the challenges for families and children in remote communities; the desirability of community-led solutions; and the role of government in addressing poverty and disadvantage. More information and online registration: Annual Leneen Forde Public Address: 8 September 2015 This event is FREE FOR MEMBERS so for information about how to join go to JOIN US or if you are already a member please remember to renew your membership now. -

The Northern Territory 'Emergency Response'

Chapter 3 197 The Northern Territory ‘Emergency Response’ intervention – A human rights analysis On 21 June 2007, the Australian Government announced a ‘national emergency response to protect Aboriginal children in the Northern Territory’ from sexual abuse and family violence.1 This has become known as the ‘NT intervention’ or the ‘Emergency Response’. The catalyst for the measures was the release of Report of the Northern Territory Board of Inquiry into the Protection of Aboriginal Children from Sexual Abuse, titled Ampe Akelyernemane Meke Mekarle: ‘Little Children are Sacred’. In the following months the emergency announcements were developed and formalised into a package of Commonwealth legislation which was passed by the federal Parliament and received Royal Assent on the 17 August 2007. The Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission welcomed the Australian Government’s announcements to act to protect the rights of Indigenous women and children in the Northern Territory. In doing so, the Commission urged the government and Parliament to adopt an approach that is consistent with Australia’s international human rights obligations and particularly with the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth).2 This chapter provides an overview of the NT emergency intervention legislation and approach more generally. It considers the human rights implications of the approach adopted by the government. Many details of how the intervention will work remain to be seen, and so the analysis here is preliminary. It seeks to foreshadow significant human rights concerns that are raised by the particular approach adopted by the government, and proposes ways forward to ensure that the intervention is consistent with Australia’s human rights obligations as embodied in legislation such as the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth). -

Index of Indigenous Health Articles in the Sydney Morning Herald

The Media and Indigenous Policy Project Index of Indigenous Health Articles in the Sydney Morning Herald 1988-89, 1994-95, 2002-03 & 2006-07 Compiled by Monica Andrew University of Canberra The articles in this index were collected from the Factiva database. Further information on the methodology for collecting newspaper articles for this project is available at http://www.canberra.edu.au/faculties/arts-design/research/research- centres/news-and-media-research-centre/events/the-media-and-indigenous-policy/the- media-and-indigenous-policy-database © Monica Andrew, 2013 Andrew, Monica (2013), Index of Indigenous Health Articles in the Sydney Morning Herald, 1988-89, 1994-95, 2002-03 & 2006-07, Media and Indigenous Policy Project, University of Canberra. http://www.canberra.edu.au/faculties/arts-design/research/research-centres/news-and-media- research-centre/events/the-media-and-indigenous-policy/the-media-and-indigenous-policy- database Further information about the Media and Indigenous Policy project is available at http://www.canberra.edu.au/faculties/arts-design/research/research-centres/news-and-media- research-centre/events/the-media-and-indigenous-policy The Media and Indigenous Policy project was supported under the Australian Research Council’s Discovery Projects funding scheme (DP0987457), with additional funding supplied by the Faculty of Arts and Design, University of Canberra. Sydney Morning Herald 1988 Title: The year of black protest Publication: Sydney Morning Herald Publication date: Monday, 4 January 1988 Writer(s): News genre: Editorial Page number: 8 Word length: 554 News source: Opinion First spokesperson: Unknown Second spokesperson: Synopsis: Discussion of Aboriginal protests during the Bicentenary year. -

Each Year the Australian of the Year Awards Provide an Opportunity to Recognise Someone Who Inspires Us and Makes Us Proud. Whet

Each year the Australian of the Year Awards provide an opportunity to recognise someone who inspires us and makes us proud. Whether you call it Australia Day, Invasion Day or Survival Day, the 26th of January provides an opportunity to acknowledge successful and inspiring Australians and what they add to this nation—acts of recognition such as these are building blocks for reconciliation. Did you know…? In 1968, the world champion bantamweight boxer Lionel Rose became the first Aboriginal Australian to receive the Australian of the Year Award. Evonne Goolagong was named Australian of the Year in 1971, on the day that the Aboriginal Tent Embassy was erected in front of Parliament House. Neville Bonner became Australia’s first Aboriginal Senator. He was Australian of the Year in 1979. Brothers Galarrwuy and Mandawuy Yunupingu have both won Australian of the Year awards. Galarrwuy in 1978 for his advocacy of Aboriginal land rights and Mandawuy in 1992 for his work as principal of the Yirrkala School and as founder of Yothu Yindi. Some quick stats 12 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians were state and territory finalists for the 2013 Australia Day Awards. Evonne Goolagong won 7 Grand Slam tennis titles. 244 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians were nominated in 2013 (over 10 per cent of total nominees) for their contribution to Australia1. Neville Bonner served in the Commonwealth Parliament for years as Senator. 12 1 Note: This number only reflects nominations received after 1 July 2012 as the application form for nominations made before this time did not have a tickable box to identify Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander nominees. -

Reporting Back: the Northern Territory Intervention One Year On

Reporting Back: The Northern Territory Intervention One Year On Address to Aboriginal Support Group, Manly Warringah Pittwater JEFF McMULLEN “The road to emancipation is a very long one,” Charles Perkins ANU academic, Professor Helen Hughes, Dr Gary Johns of the once told me. “Be patient,” he said. Bennelong Society and others, who want Aboriginal people to As I travel often through the heartland of Australia I think of give up their right to Cultural autonomy. his words and of how we are going to lift our nation to the unity The resort to social engineering and pressuring Aboriginal of purpose that will make us a truly great society. people off their traditional lands and towards the suburban Equality right now is a hope, not a reality. housing estates is the kind of intervention that comes when The Governor-General, Major General Michael Jeffery, who our nation fails to live up to its responsibility to create equal recently left office after five years, was on the front pages of opportunity for Australians wherever they live. the newspapers suggesting that Indigenous disadvantage is When you have failed to deliver to some Australian confined mainly to about 100,000 Aborigines mostly living in communities what all of us need to bring up our children in the remote north. safety and good health, you have the pre-conditions for a It is a careless choice of words by a well-intentioned man radical intervention. who has travelled remote Australia with his wife and has a very I choose these words now, very carefully. good idea of the distressing conditions so many Aboriginal The Northern Territory Intervention was conceived as a families endure in remote communities. -

Alcohol & Drugs

The Media and Indigenous Policy Project Index of Indigenous Health Articles Alcohol & Drugs The Australian, Courier-Mail & Sydney Morning Herald 1988-89, 1994-95, 2002-03 & 2006-07 Compiled by Monica Andrew University of Canberra The articles in this index from The Australian and the Courier-Mail from 1988-89 and 1994- 95 were collected from newspaper clipping files held at the Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Study (AIATSIS) library. The researchers are grateful to AIATSIS for allowing access to their facilities. All articles from the Sydney Morning Herald and articles from 2002-03 and 2006-07 from The Australian and the Courier-Mail were collected from the Factiva database. Further information on the methodology for collecting newspaper articles for this project is available at http://www.canberra.edu.au/faculties/arts-design/research/research- centres/news-and-media-research-centre/events/the-media-and-indigenous-policy/the- media-and-indigenous-policy-database © Monica Andrew, 2013 Andrew, Monica (2013), Index of Indigenous Health Articles, Alcohol & Drugs in The Australian, 1988-89, 1994-95, 2002-03 & 2006-07, Media and Indigenous Policy Project, University of Canberra. http://www.canberra.edu.au/faculties/arts-design/research/research-centres/news-and-media- research-centre/events/the-media-and-indigenous-policy/the-media-and-indigenous-policy-database Further information about the Media and Indigenous Policy project is available at http://www.canberra.edu.au/faculties/arts-design/research/research-centres/news-and-media- research-centre/events/the-media-and-indigenous-policy The Media and Indigenous Policy project was supported under the Australian Research Council’s Discovery Projects funding scheme (DP0987457), with additional funding supplied by the Faculty of Arts and Design, University of Canberra. -

Keyword: Indigenous Health Standards

The Media and Indigenous Policy Project Index of Indigenous Health Articles Indigenous Health Standards The Australian, Courier-Mail & Sydney Morning Herald 1988-89, 1994-95, 2002-03 & 2006-07 Compiled by Monica Andrew University of Canberra The articles in this index from The Australian and the Courier-Mail from 1988-89 and 1994- 95 were collected from newspaper clipping files held at the Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Study (AIATSIS) library. The researchers are grateful to AIATSIS for allowing access to their facilities. All articles from the Sydney Morning Herald and articles from 2002-03 and 2006-07 from The Australian and the Courier-Mail were collected from the Factiva database. Further information on the methodology for collecting newspaper articles for this project is available at http://www.canberra.edu.au/faculties/arts-design/research/research- centres/news-and-media-research-centre/events/the-media-and-indigenous-policy/the- media-and-indigenous-policy-database © Monica Andrew, 2013 Andrew, Monica (2013), Index of Indigenous Health Articles, Indigenous Health Standards, in The Australian, 1988-89, 1994-95, 2002-03 & 2006-07, Media and Indigenous Policy Project, University of Canberra. http://www.canberra.edu.au/faculties/arts-design/research/research-centres/news-and- media-research-centre/events/the-media-and-indigenous-policy/the-media-and-indigenous-policy- database Further information about the Media and Indigenous Policy project is available at http://www.canberra.edu.au/faculties/arts-design/research/research-centres/news-and-media- research-centre/events/the-media-and-indigenous-policy The Media and Indigenous Policy project was supported under the Australian Research Council’s Discovery Projects funding scheme (DP0987457), with additional funding supplied by the Faculty of Arts and Design, University of Canberra. -

Woolworths Proud to Support Great Young Australians

MEDIA RELEASE 22 JANUARY 2016 WOOLWORTHS PROUD TO SUPPORT GREAT YOUNG AUSTRALIANS The National Australia Day Council is proud to announce Woolworths as a sponsor of the Young Australian of the Year category in the Australian of the Year Awards. The Young Australian of the Year category recognises the achievements and contributions of Australians aged 16 to 30 years. Introduced to the Australian of the Year Awards in 1979, the Young Australian of the Year Award has recognised a diverse range of young leaders and achievers from areas such as medicine, advocacy, arts, business, Indigenous affairs, community relations and sport. Among the roll call of great Young Australians are Olympic legends Cathy Freeman and Ian Thorpe, anti-poverty campaigner Hugh Evans, entrepreneur Poppy King, round the world sailor Jessica Watson, conductor Simone Young, Indigenous youth advocate Tania Major, palaeontologist Scott Hucknull and anti-violence campaigner Jonty Bush. National Australia Day Council Chairman, Mr Ben Roberts-Smith VC MG, welcomed the new partnership with Woolworths. “Woolworths has a long and proud history in Australia and is respected as a corporation which supports innovation, diversity and our youth – values reflected in the Young Australian of the Year Award recipients and finalists each year,” said Mr Roberts-Smith. “Woolworths has a long track record of supporting young people who go on to play leadership roles at a senior management level within its own organisation and at a national level. There’s a great culture of supporting the potential in people.” Woolworths Director Corporate and Public Affairs, Peter McConnell, said the sponsorship of the Young Australian of the Year Award is a great way for an iconic Australian company to give back to the community. -

A Grounded Theory of Empowerment

This file is part of the following reference: Bainbridge, Roxanne (2009) Cast all imaginations: Umbi speak. PhD thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/8235 Cast All Imaginations: Umbi Speak Thesis submitted by Roxanne BAINBRIDGE BSocSc (Hons) in June 2009 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Indigenous Australian Studies James Cook University Statement of Access I, the undersigned, author of this work, understand that James Cook University will make this thesis available for use within the University Library and, via the Australian Digital Theses network, for use elsewhere. I understand that, as an unpublished work, a thesis has significant protection under the Copyright Act and; I do not wish to place any further restriction on access to this work. Or I wish this work to be embargoed until : Or I wish the following restrictions to be placed on this work : _________________________ ______________ Signature Date ii Statement of Sources Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at any university or other institution of tertiary education. Information derived from the published or unpublished work of others has been acknowledged in the text and a list of references is given. ____________________ ____________________ Signature Date iii Statement of Contribution of Others Including Financial and Editorial Help The Faculty of Arts, Education and Social Sciences at James Cook University provided a Postgraduate Research Scholarship over the course of my candidature. A professional administration service, Al Rinn Admin Specialists, was engaged to prepare the thesis for submission. -

Child Health

The Media and Indigenous Policy Project Index of Indigenous Health Articles Child Health The Australian, Courier-Mail & Sydney Morning Herald 1988-89, 1994-95, 2002-03 & 2006-07 Compiled by Monica Andrew University of Canberra The articles in this index from The Australian and the Courier-Mail from 1988-89 and 1994- 95 were collected from newspaper clipping files held at the Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Study (AIATSIS) library. The researchers are grateful to AIATSIS for allowing access to their facilities. All articles from the Sydney Morning Herald and articles from 2002-03 and 2006-07 from The Australian and the Courier-Mail were collected from the Factiva database. Further information on the methodology for collecting newspaper articles for this project is available at http://www.canberra.edu.au/faculties/arts-design/research/research- centres/news-and-media-research-centre/events/the-media-and-indigenous-policy/the- media-and-indigenous-policy-database © Monica Andrew, 2013 Andrew, Monica (2013), Index of Indigenous Health Articles, Child Health, in The Australian, 1988-89, 1994-95, 2002-03 & 2006-07, Media and Indigenous Policy Project, University of Canberra. http://www.canberra.edu.au/faculties/arts-design/research/research-centres/news-and-media- research-centre/events/the-media-and-indigenous-policy/the-media-and-indigenous-policy- database Further information about the Media and Indigenous Policy project is available at http://www.canberra.edu.au/faculties/arts-design/research/research-centres/news-and-media- research-centre/events/the-media-and-indigenous-policy The Media and Indigenous Policy project was supported under the Australian Research Council’s Discovery Projects funding scheme (DP0987457), with additional funding supplied by the Faculty of Arts and Design, University of Canberra.