The Intersectional Life and Times of Lutie A. Lytle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fair Treatment? African-American Presence at International Expositions in the South, 1884 – 1902

FAIR TREATMENT? AFRICAN-AMERICAN PRESENCE AT INTERNATIONAL EXPOSITIONS IN THE SOUTH, 1884 – 1902 BY SARA S. CROMWELL A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN LIBERAL STUDIES December 2010 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Anthony S. Parent, Ph.D., Advisor Jeanne M. Simonelli, Ph.D., Chair John Hayes, Ph.D. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many thanks to my friends, family, and coworkers for their support, encouragement, and patience as I worked on my thesis. A special thank you to the Interlibrary Loan Department of the Z. Smith Reynolds Library for their invaluable assistance in my research. And finally, thanks to Dr. Parent, Dr. Simonelli, and Dr. Hayes for their helpful advice throughout the process. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................... iv ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER ONE WORLD‘S INDUSTRIAL AND COTTON CENTENNIAL EXPOSITION AT NEW ORLEANS, 1884-85 .............................................................................. 17 CHAPTER TWO A DECADE OF CHANGES .................................................................................. 40 CHAPTER THREE COTTON STATES AND INTERNATIONAL EXPOSITION -

Africana Collection

Africana Collection SPECIAL COLLECTIONS RESEARCH CENTER Sunday School, St. Mary's Church, 1907. From the Foggy Bottom Collection. A Guide to Africana Resources in the Special Collections Research Center Special Collections Research Center Gelman Library, Suite 704 Phone: 202-994-7549 Email: [email protected] http://www.gelman.gwu.edu/collections/SCRC This and other bibliographies can be accessed online at http://www.gelman.gwu.edu/collections/SCRC/research-tools/bibliographies-1 AFRICANA 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AMERICAN COLONIZATION SOCIETY ............................................................. 3 ART & MUSIC ...................................................................................................... 4 BLACK ELITE ........................................................................................................ 5 CIVIL RIGHTS ...................................................................................................... 6 EDUCATION ....................................................................................................... 7 EMPLOYMENT .................................................................................................. 11 FEDERAL GOVERNMENT ................................................................................. 14 FOGGY BOTTOM /GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY ............................ 15 GENEALOGY .................................................................................................... 16 GENERAL HISTORY.......................................................................................... -

2009-2010, Issue Ii

WBA Newsletter Page 1 of 2 2009-2010, ISSUE II In This Issue WBA Kicks Off the Year President's with Stars of the Bar Column: Answering a Call Stars of the Bar By Kerri Castellini, Feeney & Kuwamura, P.A. to Share President's Column Stars of the Bar was once again a successful kick-off By Consuela Pinto, WBA President WBA Foundation for WBA’s year. The event bustled with over 200 attorneys, judges, law students, and other members of the metropolitan legal community. The Hogan & The WBA and the American Committee & Forum Highlights Hartson building at Columbia Square was a beautiful University Washington College of setting for a night of networking and honoring Law (WCL) came together on Member News community service leaders. Current and prospective October 29, for an annual celebration members alike shared in the complimentary hors of our shared history. The theme for Feature: Working Women and d'oeuvres and beverages while learning more about the evening, Domestic Violence and Delayed Child Bearing the upcoming WBA program year. Immigration, was a timely one— October is Domestic Violence Awareness Month. Working Women and Events Delayed Child Bearing: Technological Advances Support the WBA Now Offer Women More Wed., Dec. 16, 2009 Foundation's Communications Law Forum Options Founders Holiday Tea — SOLD OUT Fellowship By Mindy Berkson, Founder, Lotus Blossom Thurs., Jan. 28, 2010 Consulting, LLC WBA Foundation By Diana M. Savit, WBA Foundation President Value Vino: Finding Great Wines No doubt, infertility is on the rise. One in five for Less couples today will struggle with infertility—the biological inability to conceive or carry a pregnancy The WBA Foundation established its to full term. -

Pathfinderlegal00mattrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley This manuscript is made available for research purposes. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California at Berkeley. Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the Regional Oral History Office, 486 Library, and should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user. The Bancroft Library University of California/Berkeley Regional Oral History Office Suffragists Oral History Project Burnita Shelton Matthews PATHFINDER IN THE LEGAL ASPECTS OF WOMEN With an Introduction by Betty Poston Jones An Interview Conducted by Amelia R. Fry Copy No. (c) 1975 by The Regents of the University of California Judge Burnita Shelton Matthews Early 1950s THE YORK TIMES OBITUARIES THURSDAY, APRIL 28, 1988 Burnita 5. Matthews Dies at 93; First Woman on U.S. Trial Courts By STEVEN GREENHOUSE Special to The New York Times WASHINGTON, April 27 Burnita "The reason I always had women," Shelton Matthews, the first woman to she said, "was because so often, when a serve as a Federal district judge, died woman makes good at something they here Monday at the age of 93 after a always say that some man did it. So I stroke. just thought it would be better to have Judge Matthews was named to the women. I wanted to show my confi Federal District Court for the District dence in women." of Columbia President Truman in by Sent to Music School 1949. -

White Plague, White City: Landscape and the Racialization of Tuberculosis in Washington, D.C

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2019 White Plague, White City: Landscape and the Racialization of Tuberculosis in Washington, D.C. from 1846 to 1960 Ivie Orobaton Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the African American Studies Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Orobaton, Ivie, "White Plague, White City: Landscape and the Racialization of Tuberculosis in Washington, D.C. from 1846 to 1960" (2019). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1378. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1378 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction: Why Tuberculosis? Why Washington, D.C.?......................................................3-7 Chapter 1: The Landscape of Washington, D.C. and the Emergence of Tuberculosis in the City …………………………………………………………………………………………………8-21 Chapter 2: Practical Responses to the Tuberculosis Issue (1846-1910)…………………….22-37 Chapter 3: Ideological Debates Around the Practical Responses to Tuberculosis (1890-1930) …….………………………………………………………………………………………….38-56 Conclusion: The Passing of the Debate and the End of Tuberculosis in the City (1930-1960) ………………………………………….…………………………………………………….57-58 -

Frederick Douglass and Public Memories of the Haitian Revolution James Lincoln James Madison University

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2015 Memory as torchlight: Frederick Douglass and public memories of the Haitian Revolution James Lincoln James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the Cultural History Commons, Intellectual History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Lincoln, James, "Memory as torchlight: Frederick Douglass and public memories of the Haitian Revolution" (2015). Masters Theses. 23. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/23 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Memory as Torchlight: Frederick Douglass and Public Memories of the Haitian Revolution James Lincoln A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History May 2015 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………………......1 Chapter 1: The Antebellum Era………………………………………………………….22 Chapter 2: Secession and the Civil War…………………………………………………66 Chapter 3: Reconstruction and the Post-War Years……………………………………112 Epilogue………………………………………………………………………………...150 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………154 ii Abstract The following explores how Frederick Douglass used memoires of the Haitian Revolution in various public forums throughout the nineteenth century. Specifically, it analyzes both how Douglass articulated specific public memories of the Haitian Revolution and why his articulations changed over time. Additional context is added to the present analysis as Douglass’ various articulations are also compared to those of other individuals who were expressing their memories at the same time. -

Federal Surveillance of Afro-Americans (1917-1925)

Revised and Updated FEDERAL SURVEILLANCE OF AFRO-AMERICANS (1917-1925): The First World War, the Red Scare, and the Garvey Movement UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES: Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections August Meier and Elliott Rudwick General Editors FEDERAL SURVEILLANCE OF AFRO-AMERICANS (1917-1925): The First World War, the Red Scare, and the Garvey Movement FEDERAL SURVEILLANCE OF AFRO-AMERICANS (1917-1925): The First World War, the Red Scare, and the Garvey Movement Edited by Theodore Kornweibel, Jr. Associate Editors Randolph Boehm and R. Dale Grinder Guide Compiled by Martin Schipper A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA, INC. 44 North Market Street • Frederick, MD 21701 NOTE ON SOURCES Materials reproduced in this microfilm publication derive from the National Archives, Washington, D.C.; Washington Federal Records Center, Suitland, Maryland; Federal Records Centers in Ft. Worth, Texas and Bayonne, New Jersey; and from the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Freedom of Information Act Office. Materials from the National Archives include selections from: Record Group 28, U.S. Postal Service Record Group 32, U.S. Shipping Board Record Group 38, Office of Naval Intelligence Record Group 59, U.S. Department of State Record Group 60, U.S. Department of Justice Record Group 65, Federal Bureau of Investigation Record Group 165, War Department: General and Special Staffs- Military Intelligence Division Materials from the Washington Federal Records Center, Suitland, Maryland include selections from: Record Group 165, War Department: General and Special Staffs- Military Intelligence Division Record Group 185, U.S. Panama Canal Commission Materials from the Federal Records Centers in Ft. -

African American Postal Workers in the 19Th Century Slaves in General

African American Postal Workers in the 19th Century African Americans began the 19th century with a small role in postal operations and ended the century as Postmasters, letter carriers, and managers at postal headquarters. Although postal records did not list the race of employees, other sources, like newspaper accounts and federal census records, have made it possible to identify more than 800 African American postal workers. Included among them were 243 Postmasters, 323 letter carriers, and 113 Post Office clerks. For lists of known African American employees by position, see “List of Known African American Postmasters, 1800s,” “List of Known African American Letter Carriers, 1800s,” “List of Known African American Post Office Clerks, 1800s,” and “List of Other Known African American Postal Employees, 1800s.” Enslaved African Americans Carried Mail Prior to 1802 The earliest known African Americans employed in the United States mail service were slaves who worked for mail transportation contractors prior to 1802. In 1794, Postmaster General Timothy Pickering wrote to a Maryland resident, regarding the transportation of mail from Harford to Bel Air: If the Inhabitants . should deem their letters safe with a faithful black, I should not refuse him. … I suppose the planters entrust more valuable things to some of their blacks.1 In an apparent jab at the institution of slavery itself, Pickering added, “If you admitted a negro to be a man, the difficulty would cease.” Pickering hated slavery with a passion; it was in part due to his efforts that the Northwest Slaves in general are 2 Ordinance of 1787 forbade slavery in the territory north of the Ohio River. -

Guide to the Collection of Materials on the National Association of Negro Musicians (NANM)

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago CBMR Collection Guides / Finding Aids Center for Black Music Research 2020 Guide to the Collection of Materials on the National Association of Negro Musicians (NANM) Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cmbr_guides Part of the History Commons, and the Music Commons Columbia COLLEGE CHICAGO CENTER FOR BLACK MUSIC RESEARCH COLLECTION Collection of Materials on the National Association of Negro Musicians (NANM), 1919-2004 EXTENT 9 boxes, 5.7 linear feet COLLECTION SUMMARY The collection contains materials about the National Association of Negro Musicians and its history and activities, particularly the primary documents included in A Documentary History of the National Association of Negro Musicians, edited by Doris Evans McGinty (Chicago: Center for Black Music Research, 2004) plus correspondence concerning the compilation of the book, other NANM administrative correspondence and records, meeting programs, concert programs, photographs, and other materials. HISTORICAL NOTE The National Association of Negro Musicians (NANM) was founded in Chicago in 1919 by a group of African-American professional musicians and composers to advance the education and careers of African-American musicians. Among the founders of the organization were Nora Douglas Holt, Henry Lee Grant, Gregoria Fraser Goins, R. Nathaniel Dett, Clarence Cameron White, Carl Diton, and Kemper Harreld, among others. During its history, the NANM has sponsored a scholarship contest for performers since 1919 and administered the Wanamaker Prize for composition (offered between 1927 and 1932). There are local branches of NANM in many large cities, as well as student chapters and regional organizations. -

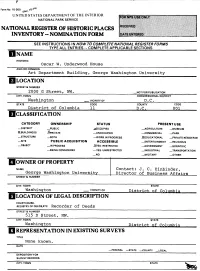

NOMINATION FORM Hi

Form No. 10-300 U m I tlJ a l A 1 ta UtrAK. l ivitFN i wr i nc, ii> i c,i\.iv^n. NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Hi NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES HI INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM mi SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Oscar W. Underwood House AND/OR COMMON Art Department Building, George Washington University LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 2000 G Street, NW. —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Washington __ VICINITY OF D.C. STATE CODE COUNTY CODE District of Columbia 11 D.C. 001 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC —JflDCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) .^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS ^EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —XYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Contact: J. C. Einbinder, George Washington University Director of Business Affairs STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Washington VICINITY OF District of Columbia LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Recorder of Deeds STREET & NUMBER 515 D Street, NW, CITY. TOWN STATE Washington District of Columbia REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE None known. DATE FEDERAL _STATE COUNTY LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED _3S3RIGINAL SITE —XGOOD —RUINS _>JALTERED —MOVED DATE_______ —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Senator Oscar W. Underwood resided in this north-facing 2^-story, mansard-roofed, 19th-century, brick rowhouse from 1914 to 1925. -

The Founding of the Washington College of Law: the First Law School Established by Women for Women

THE FOUNDING OF THE WASHINGTON COLLEGE OF LAW: THE FIRST LAW SCHOOL ESTABLISHED BY WOMEN FOR WOMEN MARY L. CLARK* TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................................................ 614 I. The Early Lives of Ellen Spencer Mussey and Emma Gillett and the Founding of the Woman's Law Class in 1896 ........... 616 A. Ellen Spencer Mussey ........................................................ 616 B. Em m a Gillett ...................................................................... 625 C. Mussey and Gillett as Prototypes of Early Women Lawyers ............................................................................... 629 II. The History of the Woman's Law Class and the Founding of the Washington College of Law in 1898 ............................. 633 A. Factors Shaping Mussey and Gillett's Decision to Found a Law School Primarily for Women ...................... 635 1. The expansion of women's higher education opportunities ................................................................ 635 2. The growth of women's voluntary associations .......... 639 3. The rise of the women's suffrage movement ............. 642 4. Mussey and Gillett's personal struggles to obtain legal instruction in Washington, D.C ......................... 644 Teaching Fellow and Adjunct Professor, Georgetown University Law Center. J.D., HaroardLaw School A.B., Bryn Mawr College The author wishes to thank Richard Chused, Dan- iel Ernst, Steven Goldblatt, Carrie Menkel-Meadow, Judith Resnik, Robin West, Wendy Wil- liams, and the participants in Georgetown's Summer 1997 Faculty Research Workshop for their thoughtful critiques of earlier drafts of this Article. Thanks also to Barbara Babcock and Vir- ginia Drachman for their helpful suggestions with regard to women's history. Any errors re- main my own, of course. 613 THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 47:613 B. Mussey and Gillett's Adoption of a Coeducational Form at ............................................................................... -

The Future of Women Law Professors

The Future of Women Law Professors Herma Hill Kay* . THE PAST: 1896-1945 Women began teaching law so that other women could learn law. The first women to instruct law students were practitioners who accepted women to study in their law offices. In 1896, Ellen Spencer Mussy and Emma Gillett offered a series of part-time courses to three women students in Mussy's law office in the District of Columbia.' At the time, only one of the five law schools operating in the District admitted women: Howard University.2 Mussy and Gillett must have been shocked to learn, two years later, that no law school would admit their three students so they could complete their training. Thereupon, the two women founded a law school of their own-Washington College of Law-in 1898. Ellen Spencer Mussy became the school's founding dean, a post she held until 1914. Five other women deans followed her in an unbroken line until 1947, when the school was accepted for membership in the Association of American Law Schools (AALS).3 All subsequent deans of Washington College have been men. In 4 1949, Washington became affiliated with American University. The first woman law professor appointed to a tenure-track position in an American Bar Association (ABA)-approved, AALS-member school was Barbara Nachtrieb Armstrong, who began her academic career in 1919 at the University of California, Berkeley.5 Professor Armstrong earned her Ph.D. in economics in 1921. Her initial appointment was a joint post as a *Richard R. Jennings, Professor of Law, University of California, Berkely, School of Law.