An African Alternative : Nordic Migration to South Africa, 1815-1914

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selskapskontroll Av Renovasjonsselskapet for Farsund Og Lyngdal AS

KRISTIANSAND REVISJONSDISTRIKT IKS 9 Kristiansand Søgne Songdalen Vennesla Selskapskontroll av Renovasjonsselskapet for Farsund og Lyngdal AS Kristiansand februar 2011 Postadr.: Postboks 417, Lund Hovedkontor Kristiansand Søgne Songdalen Vennesla 4604 Kristiansand Telefon: 38 07 27 00 Tlf 38 05 55 43 Tlf 38 18 33 33 Tlf 38 13 72 18 Kontoradr.: Tollbodgt 6 Telefaks: 38 07 27 20 Org.nr.: NO 987 183 918 e-post: [email protected] Kristiansand Revisjonsdistrikt IKS Selskapskontroll i RFL AS Innhold 0 Sammendrag........................................................................................................4 1 Innledning ............................................................................................................5 1.1 Bakgrunn for selskapskontrollen ....................................................................5 1.2 Formålet med selskapskontrollen...................................................................5 1.3 Problemstillinger, metode og gjennomføring ..................................................7 1.4 Kriterier...........................................................................................................8 1.5 Rapportering ..................................................................................................8 2 Fakta om selskapet .............................................................................................9 3 Kommunens eierskapspolitikk og eierstrategi ...............................................10 3.1 Eierskapspolitikken.......................................................................................10 -

01 Agder Kommunesammenslåing

Veien til færre og større Agder-kommuner Her er oversikt over status på prosessene SIRDAL: Ønsker primært å stå alene. Er også involvert i VEST-AGDER rundt kommunesammenslåing i alle mulighetsstudiet «Langfjella» (Sirdal, Valle, Bykle, Vinje, og Bygland), men har satt det på vent. 180 877 innbyggere AUST-AGDER kommunene i Agder-fylkene. ÅSERAL: Kommunestyret vedtok 25. juni med 9 mot 8 stemmer å stå alene. Alternativene er 114 767 innbyggere «Midtre Agder» og «Indre Agder» (Åseral, Bygland, Evje og Hornnes) Saken skal opp 1838 BYKLE 933 ÅMLI: SIRDAL Kommunestyret takket igjen 3. september, og det skal holdes BYKLE: rådgivende folkeavstemning 14. september. Kommunestyret vedtok 25. juni å 18. juni ja til videre UTSNITT utrede «nullalternativet». De vil sonderinger med også utrede sammenslåing med Froland. Takket også ja KVINESDAL: til sonderinger med ÅSERAL 925 Valle og Bygland i «Setesdal»- Foreløpig uklar situasjon, sak framlegges for alternativet, og ønsker drøftinger Nissedal i Telemark. formannskapet 1. september. Opprinnelig om aktuelle samarbeidsområder med i «Lister 5» som har strandet, «Lister 3» med Vinje og Sirdal. vil muligens bli vurdert. Men ønsker også VEGÅRSHEI: GJERSTAD: RISØR: 5948 Sirdal med på laget. KVINESDAL VALLE 1251 Kommunestyret vedtok Ønsker å gå videre med Bystyret oppfordret 28. mai de 16. juni at de er best «Østregionen» (Gjerstad, fire kommunene i «Østregionen» VALLE: tjent med å stå alene, Vegårdshei, Tvedestrand å utrede sammenslåing. HÆGEBOSTAD: Formannskapet vedtok 24. juni å Kommunestyret sa 18. juni ja til å forhandle både men vil også vurdere og Risør). Vurderer også Arbeidet med Østre Agder går utrede «nullaltenativet», altså å stå «Østre Agder» og om Åmli bør være med, parallelt, og kommunestyret om «Midtre Agder» (Marnardal, Audnedal, alene. -

SVR Brosjyre Kart

VERNEOMRÅDA I Setesdal vesthei, Ryfylkeheiane og Frafjordheiane (SVR) E 134 / Rv 13 Røldal Odda / Hardanger Odda / Hardanger Simlebu E 134 13 Røldal Haukeliseter HORDALAND Sandvasshytta E 134 Utåker Åkra ROGALAND Øvre Sand- HORDALAND Haukeli vatnbrakka TELEMARK Vågslid 520 13 Blomstølen Skånevik Breifonn Haukeligrend E 134 Kvanndalen Oslo SAUDA Holmevatn 9 Kvanndalen Storavassbu Holmevassåno VERNEOMRÅDET Fitjarnuten Etne Sauda Roaldkvam Sandvatnet Sæsvatn Løkjelsvatnhytta Saudasjøen Skaulen Nesflaten Varig verna Sloaros Breivatn Bjåen Mindre verneområdeVinje Svandalen n e VERNEOMRÅDAVERNEOVERNEOMRÅDADA I d forvalta av SVR r o Bleskestadmoen E 134 j Dyrskarnuten f a Ferdselsrestriksjonar: d Maldal Hustveitsåta u Lislevatn NR Bråtveit ROGALAND Vidmyr NR Haugesund Sa Suldalsvatnet Olalihytta AUST-AGDER Lundane Heile året Hovden LVO Hylen Jonstøl Hovden Kalving VINDAFJORD (25. april–31. mai) Sandeid 520 Dyrskarnuten Snønuten Hartevatn 1604 TjørnbrotbuTjø b tb Trekk Hylsfjorden (15. april–20. mai) 46 Vinjarnuten 13 Kvilldal Vikedal Steinkilen Ropeid Suldalsosen Sand Saurdal Dyraheio Holmavatnet Urdevasskilen Turisthytter i SVR SULDAL Krossvatn Vindafjorden Vatnedalsvatnet Berdalen Statsskoghytter Grjotdalsneset Stranddalen Berdalsbu Fjellstyrehytter Breiavad Store Urvatn TOKKE 46 Sandsfjorden Sandsa Napen Blåbergåskilen Reinsvatnet Andre hytter Sandsavatnet 9 Marvik Øvre Moen Krokevasskvæven Vindafjorden Vatlandsvåg Lovraeid Oddatjørn- Vassdalstjørn Gullingen dammen Krokevasshytta BYKLE Førrevass- Godebu 13 dammen Byklestøylane Haugesund Hebnes -

Audnedal Kommune Teknisk/Næring

Audnedal kommune Teknisk/Næring Olje og Energi Departementet Vår Ref: Ordningsverdi: Saksbehandler: Deres Ref: Dato: 2019/154 - 25 S41 Terje Ågedal 27.09.2019 INNSPILL TIL HØRING OM NASJONAL RAMME FOR VINDKRAFTUTBYGGING Kommunens høringssvar er sendt departementet tidligere. Der Audnedal kommunestyre sier nei til utbygging av landbasert vindkraft i vår kommune. Vedlagte innspill fra grunneiere på Flottorp, med dokumentasjon av artsmangfold er mottatt av Audnedal kommune, og videresendes departementet. Vi ber om at det tas hensyn til dette ved vurdering av eventuell vindkraftutbygging. Med hilsen Terje Ågedal Saksbehandler Vedlegg 1 Artsmangfold - Hægebostad - Audnedal 2 Artsmangfold Dagfinn Flottorp 3 Artsmangfold Kvinesdal - Audnedal 4 Uttalelse fra Grindheim Helselag 5 Innsigelse fra grunneiere Postadresse: Besøksadresse: Telefon: 38 28 20 00 Internett: www.audnedal.kommune.no Rådhuset Rådhuset, 4525 Telefaks: 38 28 20 99 E-post: [email protected] Konsmogarden 6 KonsmoRådhuset Bank kto.: 3129 20 09804 Org.nr.: 964 966 753 4525 Konsmo Konsmogarden 6 4525 Konsmo Til Hægebostad kommune Hægebostad,19.08.19 Innspill ifm den nasjonale rammen for vindkraft på land. I forbindelse med overnevnte ønsker vi å videreformidle viktig info som berører Hægebostad kommune. Ønsker å videreformidle feltbefaringer og kartlegging som har pågått gjennom flere år. Jeg, Svein Hovden har ferdes i disse områdene omkring 35 år som aktiv friluftsmann med interesse for jakt og fiske. I de senere år har det vært mer som ornitolog. Spesielt de siste 10 – 15 årene har det blitt mye registering av fugler, dyr og dyretråkk. Jeg har en spesiell forkjærlighet til orrfugl leiker og har kartlagt leiker over flere år. Har utallige netter ute i det fri. -

Copyright © and Moral Rights for This Thesis Are Retained by the Author And/Or Other Copyright Owners

McDonald, Jared. (2015) Subjects of the Crown: Khoesan identity and assimilation in the Cape Colony, c. 1795- 1858. PhD thesis. SOAS University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/22831/ Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Subjects of the Crown: Khoesan Identity and Assimilation in the Cape Colony, c.1795-1858 Jared McDonald Department of History School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) University of London A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in History 2015 Declaration for PhD Thesis I declare that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the thesis which I present for examination. -

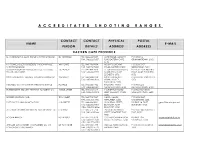

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714 -

Supplement to the London Gazette, 22 August, 1918. 9797

SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 22 AUGUST, 1918. 9797 Maj. Donald David Coghill Murray, 5th Mtd. 17th Mounted Rifles (Western Province Rifles)^ Bde. (Supernumerary List). Lt.-Col. Petrus Benjamin Van Der West- Maj. Wilfred Joah Nussey, 4th Mtd. Bde. huizen. * (Supernumerary List). Capt. (T./Maj.) Robert Boss Pcrrott (Railway 20th Mounted Rifles (Graaf Reinet Ruiters}^ Regt.). Lt.-Col. Jan Stephanus Van Zyl. Col. Comdt. Schalk Willem Pijper, 5th Mtd. Bde. COMMANDOS. Maj. Nicholas Kingswell Prettejohn (Super- numerary List). Botha's Hogeveld Ruiters. Maj. Hendrik Stephanus Pretorius, 4th Mtd. Lt.-Col. Ivan Victor .Swemmer. Bde. (Supernumerary List). Maj. Richard Morrison Tanner, 7th Mtd. Bde. Botha's Natal Horse. (1st Mtd. Rifles). Lt.-Col. Theunis Botha. Col. Dirk Jacob Carl Bekker Van De Venter, 4th Mtd. Bde. (10th Dismtd. Rif.). Bethel Commando. Lt.-Col. (T./Col.) James Scott Wylie, M.V.O., Lt.-Col. Jacobus De Villiers. V.D., 4th Infy. Bde. (1st Infy.). Bloemhof Commando. ARTILLERY. Lt.-Col. Johannes Jacobus Bezuidenhout. &th Permanent Battery (S.A.M.R.). Capt. (T./Maj.) Jan Francois Wolmarans. Brit'stown Commando. Maj. Johannes Marthinus Nicolas Breedt. 6th Citizen Battery. Maj. Charles Henry Fineran Divine, V.D. Calvinia-Kenhardt Commando. Maj. Johannes Gerhardus Stephanus Bronk- 12th Citizen Battery. horst. Maj. George Richard Owen Edwards. Maj. Pieter Arnoldus Vermaa&. (The award of a Bar to the D.S.O. is substi- Carnarvon Commando. tuted for the award of a D.S.O. to this Officer published on page 23 of the London Gazette Maj. Carl Johannes Van Zyl. dated 1st January, 1917.) Carolina Commando. Heavy Artillery. Lt.-Col. -

Mum's Diaries Copy

The War Diaries of Lensgrevinde Lucie-Marie Ludovika Anastasia Adelheid Karola Hedevig Reventlow 1940- 1945 Family Tree A Christian-Einar Agnes M. Moltke F.L.E. Reventlow Divorced First Marriage Curt l.H.G.M.E.E.Haugwitz-Hardenberg-Reventlow ___ Anna-Ermegård Abela Reventlow John Patrick Boswell ____ Lucie C.C.J. Haugwitz-Hardenberg-Reventlow Annabella (called Be) First marriage John James Patrick Curt l.H.G.M.E.E.Haugwitz-Hardenberg-Reventlow is brother to Lucie-Marie L.A.A.K.H. Haugwitz-Hardenberg-Reventlow B Christian-Einar Lucie-Marie L.A.A.K.H. F.L.E. Reventlow Haugwitz-Hardenberg- Second Marriage Reventlow First marriage Patrick H. Grinling ___ Benedicte C.H.S.E.M.M.A. Reventlow called Benika Christian Gavin Rupert (Gorm) Christian D.E.P.F. Reventlow Anastasia (Anafia) Erik Mourier ___ Naka Reventlow called Besa Ove Alli Steen Suzanne C Bertram Walker Lucie-Marie L.A.A.K.H. called Bertie Haugwitz-Hardenberg- Reventlow, called Mum Second marriage Christian-Einar died in 1929 and Lucie-Marie married Bertram in 1940 The journey from Brahetrolleborg, Fyn, Denmark, to England. Isaiah: 35 As birds Alying so will the Lord of Hosts defend Jerusalem; defending also he will deliver it; and passing over he will preserve it. England Brahetrolleborg I am homesick for you – I see you in the night, peaceful and calm with dark spires standing clearly against the moonlit sky and the Great Bear just over the church with the North Star over the bell tower, and I see you in daytime, now in these October days when the chestnut avenue is golden and a smell of moist leaves hangs all around now when the leaves are falling all over the lawn. -

Årsrapport 2016 for Slots- Og Kulturstyrelsen

Årsrapport 2016 for Slots- og Kulturstyrelsen Side 2 Oversigt over tabeller, noter og bilag ........................................................................3 1. Påtegning af det samlede regnskab……………….………………………..…………...4 2. Beretning………………………………………………….…………………………….…….…6 2.1. Præsentation af Slots- og Kulturstyrelsen………………………………………..…….…6 2.2. Årets resultater………………………………………….……………………………….….…7 2.3.1 Årets faglige resultater……………………………….………………………………….….7 2.3.2 Årets økonomiske resultat………………………….……………………………………..10 2.3. Slots- og Kulturstyrelsens hovedkonti…………………………………………..……..…13 2.4. Kerneopgaver og ressourcer……………………………………………………..……….…15 2.4.1. Opgaver og ressourcer: Skematisk oversigt…….……………………………………...15 2.5. Målrapportering………………………………………………………………………………17 2.5.1. Målrapporteringens første del: Oversigt over årets resultatopfyldelse……………17 2.5.2. Målrapporteringens anden del: Uddybende analyser og vurderinger…………….18 2.6. Forventninger til kommende år……………………………………………………………31 3. Regnskab……………………………………………………………………………………….33 3.1. Anvendt regnskabspraksis……………………………….…………………………………33 3.2. Resultatopgørelse…………………………………………………………………………….34 3.3. Resultatdisponering……………………………………….…………………………………36 3.4. Balancen…………………………………………………….…………………………………37 3.5. Egenkapitalforklaring…………………………………….…………………………………38 3.6. Likviditet og låneramme…………………………………………………………….………39 3.7. Opfølgning på lønsumsloft…………………………………………………………………..39 3.8. Bevillingsregnskabet……………………………………….………………………………..39 3.9. Udgiftsbaserede hovedkonti…………………….…………………………………….…….40 -

Streets, Seals Or Seeds As Early Manifestations of Urban Life in Turku, Finland

Streets, seals or seeds as early manifestations of urban life in Turku, Finland Liisa Seppänen In the 2000s, the studies concerning the early phases of urbanization in Finland have re-actualized after many decades. The studies have focused on Turku, which is the oldest town of the present-day Finland and has been a target for many excavations. The focus of this paper is in the beginnings of the urbanization of Turku with the questions when and why the town was founded. The questions are old and discussed in many studies since the early 20th century. In this article, these questions are reflected on the basis recent archaeo- logical findings and the circumstantial evidence from historical sources. I am presenting my interpretation about the course of events, which led to the establishment of Turku. The town was not founded on a virgin land, but it was preceded by human activities like farming and possibly gatherings of religious or commercial nature. The political circum- stances activated the planning of the town in the late 13th century, which were realized in the turn of the 13th and 14th century. It seems, that the urbanization process took several decades and probably it was not until the mid 14th century when Turku met all the bench- marks set for the medieval town. Tracing the earliest evidence red to a more appropriate place. The document is dated in Perugia on the The origins of Turku (fig. 1) have fas- 29th of January in 1229, but it does cinated Finnish historians and archa- not, however, reveal the location of eologists for more than a century. -

Action Study for Etelä-Pohjanmaan Osakesäästäjät

Tuomas Seilo Action study for Etelä-Pohjanmaan Osakesäästäjät Thesis Spring 2021 School of Business and Culture Master’s Degree Programme in International Business Management 2 (103) SEINÄJOKI UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED SCIENCES Thesis abstract Faculty: School of Business and Culture Degree programme: Master’s Degree Programme in International Business Management Specialisation: International marketing Author/s: Tuomas Seilo Title of thesis: Action study for Etelä-Pohjanmaan Osakesäästäjät Supervisor(s): Anne-Maria Aho Year: 2021 Number of pages: 79 Number of appendices: 24 The purpose of this master’s thesis is to study the activities of Etelä-Pohjanmaan Osakesäästäjät (EPOS), their development needs and prepare a development plan. The theoretical part composes of five sections: business planning, customer segmentation, service design, content marketing and leadership. Each of these sections carry out their irreplaceable roles in development and leadership of EPOS as well as other organizations in the world of digitalization and increasingly competitive operational environment. A member satisfaction survey was carried out electronically to explore the views of EPOS’ members concerning the current performance of EPOS and their critical areas of improvement. Additionally, key members of EPOS have been interviewed by phone. Benchmarking analysis was conducted by interviewing Vaasan arvopaperisijoittajat ry. which together with EPOS belongs to Finnish Shareholders’ Association. Survey results and data received by individual interviews were finally -

It Is Hoped the Necessity of Efficient Libraries As a Support To;*

DOCUMENT ED 071 ,31 LI 004 135 TITLE Advaittms in Library and Information Sciencein Finland. INSTITUTION Finnish Government, Helsinki.: PUB DATE 72 NOTE 27p.;(0 References) AVAILABLE FROMSumas larjastoseura (Finnish LibraryAssoc.); Nuseokatu 18 A, -00100 -Helsinki 10 Finland(No charge) EDPS PRICE 111-$0.65 RC Not -Available fromEDRS. DESCRIPTORS ForeignCountries; *InformationScience;Information Systems;Librarians;:Library :Collections; Library Planning;*LibraryScience; *Public -Libraries; *Research _Libraries- IDENTIFIERS *Finland; NORDDOIC; :Nordic CommitteeOn DocuMentation and infOrmition; Sciehtifidwand.Technical Information -ABSTRACT --* The reseatch,Llibitries in Finland-are inthe majOrity ofcase-libraries of universities=-and other institutionsforhigher education.:Librariect tesearch_.institutes-and=_Soms other=special libraries account for -some 20-30% of-the-total _OperatiOnalcapacity. Itishopedthe necessity of efficientlibraries as a Support to;* teaching _and research willbe_expressed:in ,a concrete way -in the revised legislation concerning. thedevelopmentof the university system. .The-developMent of publiclibraries from 1964: through 1972 is briefly traced and the develOpment ofScientific and technical information- from _1964=through 1970 is recounted..(MithortigH) -PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS COPY- U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. RIGHTED MATERIAL SY MICROFICHE ONLY EDUCATION & WELFARE HAS,REEN GRANTED fly_ . 4 ,OFFICE OF EDUCATION 3 (Jom; IICI f S JOS &Ara. TIIS DOCUMENT, HAS BEEN REPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM 1,iraty