YCAR Acpv5no3.Pdf (649.4Ko)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dignity of Santana Mondal

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 The Dignity of Santana Mondal VIJAY PRASHAD Vol. 49, Issue No. 20, 17 May, 2014 Vijay Prashad ([email protected]) is the Edward Said Chair at the American University of Beirut, Lebanon. Santana Mondal, a dalit woman supporter of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), was attacked by Trinamool Congress men for defying their diktat and exercising her franchise. This incident illustrates the nature of the large-scale violence which has marred the 2014 Lok Sabha elections in West Bengal. Serious allegations of booth capturing and voter intimidation have been levelled against the ruling TMC. Santana Mondal, a 35 year old woman, belongs to the Arambagh Lok Sabha parliamentary constituency in Hooghly district, West Bengal. She lives in Naskarpur with her two daughters and her sister Laxmima. The sisters work as agricultural labourers. Mondal and Laxmima are supporters of the Communist Party of India-Marxist [CPI(M)], whose candidate Sakti Mohan Malik is a sitting Member of Parliament (MP). Before voting took place in the Arambagh constituency on 30 April, political activists from the ruling Trinamool Congress (TMC) had reportedly threatened everyone in the area against voting for the Left Front, of which the CPI(M) is an integral part. Mondal ignored the threats. Her nephew Pradip also disregarded the intimidation and became a polling agent for the CPI(M) at one of the booths. After voting had taken place, three political activists of the TMC visited Mondal’s home. They wanted her nephew Pradip but could not find him there. On 6 May, two days later, the men returned. -

Red Bengal's Rise and Fall

kheya bag RED BENGAL’S RISE AND FALL he ouster of West Bengal’s Communist government after 34 years in power is no less of a watershed for having been widely predicted. For more than a generation the Party had shaped the culture, economy and society of one of the most Tpopulous provinces in India—91 million strong—and won massive majorities in the state assembly in seven consecutive elections. West Bengal had also provided the bulk of the Communist Party of India– Marxist (cpm) deputies to India’s parliament, the Lok Sabha; in the mid-90s its Chief Minister, Jyoti Basu, had been spoken of as the pos- sible Prime Minister of a centre-left coalition. The cpm’s fall from power also therefore suggests a change in the equation of Indian politics at the national level. But this cannot simply be read as a shift to the right. West Bengal has seen a high degree of popular mobilization against the cpm’s Beijing-style land grabs over the past decade. Though her origins lie in the state’s deeply conservative Congress Party, the challenger Mamata Banerjee based her campaign on an appeal to those dispossessed and alienated by the cpm’s breakneck capitalist-development policies, not least the party’s notoriously brutal treatment of poor peasants at Singur and Nandigram, and was herself accused by the Communists of being soft on the Maoists. The changing of the guard at Writers’ Building, the seat of the state gov- ernment in Calcutta, therefore raises a series of questions. First, why West Bengal? That is, how is it that the cpm succeeded in establishing -

03404349.Pdf

UA MIGRATION AND DEVELOPMENT STUDY GROUP Jagdish M. Bhagwati Nazli Choucri Wayne A. Cornelius John R. Harris Michael J. Piore Rosemarie S. Rogers Myron Weiner a ........ .................. ..... .......... C/77-5 INTERNAL MIGRATION POLICIES IN AN INDIAN STATE: A CASE STUDY OF THE MULKI RULES IN HYDERABAD AND ANDHRA K.V. Narayana Rao Migration and Development Study Group Center for International Studies Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 August 1977 Preface by Myron Weiner This study by Dr. K.V. Narayana Rao, a political scientist and Deputy Director of the National Institute of Community Development in Hyderabad who has specialized in the study of Andhra Pradesh politics, examines one of the earliest and most enduring attempts by a state government in India to influence the patterns of internal migration. The policy of intervention began in 1868 when the traditional ruler of Hyderabad State initiated steps to ensure that local people (or as they are called in Urdu, mulkis) would be given preferences in employment in the administrative services, a policy that continues, in a more complex form, to the present day. A high rate of population growth for the past two decades, a rapid expansion in education, and a low rate of industrial growth have combined to create a major problem of scarce employment opportunities in Andhra Pradesh as in most of India and, indeed, in many countries in the third world. It is not surprising therefore that there should be political pressures for controlling the labor market by those social classes in the urban areas that are best equipped to exercise political power. -

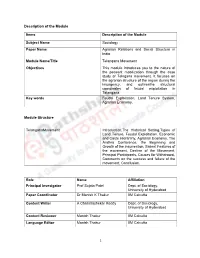

1 Description of the Module Items Description of the Module Subject

Description of the Module Items Description of the Module Subject Name Sociology Paper Name Agrarian Relations and Social Structure in India Module Name/Title Telangana Movement Objectives This module introduces you to the nature of the peasant mobilization through the case study of Telngana movement. It focuses on the agrarian structure of the region during the insurgency, and oulinesthe structural coordinates of feudal exploitation in Telangana. Key words Feudal Exploitation, Land Tenure System, Agrarian Economy. Module Structure TelanganaMovement Introduction,The Historical Setting,Types of Land Tenure, Feudal Exploitation, Economic and Caste Hierarchy, Agrarian Economy, The Andhra Conference, the Beginning and Growth of the insurrection, Salient Features of the movement, Decline of the Movement, Principal Participants, Causes for Withdrawal, Comments on the success and failure of the movement, Conclusion. Role Name Affiliation Principal Invesigator Prof Sujata Patel Dept. of Sociology, University of Hyderabad Paper Coordinator Dr Manish K Thakur IIM Calcutta Content Writer A Chandrashekar Reddy Dept. of Sociology, University of Hyderabad Content Reviewer Manish Thakur IIM Calcutta Language Editor Manish Thakur IIM Calcutta 1 Introduction: Social movements have always been an inseparable part of social progress. Through collective action, organizedprotests and resisting the structures of domination,peasant movements have historically paved the way for new thoughts and actions that revitalizes the process of social change (Singha Roy, 2004). TelanganaMovement was one such movement in the 20th century India which had ended the feudalistic oppression of landlords and the autocratic Nizam rule in the Telangana.The Telangana movement of the mid-1940s and the early 1950s was unparalleled in the 20th century history of India for its intensity, participants’ militancy and the height of revolutionism they ascended. -

India Freedom Fighters' Organisation

A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of Political Pamphlets from the Indian Subcontinent Part 5: Political Parties, Special Interest Groups, and Indian Internal Politics UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of POLITICAL PAMPHLETS FROM THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT PART 5: POLITICAL PARTIES, SPECIAL INTEREST GROUPS, AND INDIAN INTERNAL POLITICS Editorial Adviser Granville Austin Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfiche project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Indian political pamphlets [microform] microfiche Accompanied by printed guide. Includes bibliographical references. Content: pt. 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups—pt. 2. Indian Internal Politics—[etc.]—pt. 5. Political Parties, Special Interest Groups, and Indian Internal Politics ISBN 1-55655-829-5 (microfiche) 1. Political parties—India. I. UPA Academic Editions (Firm) JQ298.A1 I527 2000 <MicRR> 324.254—dc20 89-70560 CIP Copyright © 2000 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-829-5. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................. vii Source Note ............................................................................................................................. xi Reference Bibliography Series 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups Organization Accession # -

![South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 22 | 2019, “Student Politics in South Asia” [Online], Online Since 15 December 2019, Connection on 24 March 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0491/south-asia-multidisciplinary-academic-journal-22-2019-student-politics-in-south-asia-online-online-since-15-december-2019-connection-on-24-march-2021-510491.webp)

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 22 | 2019, “Student Politics in South Asia” [Online], Online Since 15 December 2019, Connection on 24 March 2021

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal 22 | 2019 Student Politics in South Asia Jean-Thomas Martelli and Kristina Garalyté (dir.) Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/5852 DOI: 10.4000/samaj.5852 ISSN: 1960-6060 Publisher Association pour la recherche sur l'Asie du Sud (ARAS) Electronic reference Jean-Thomas Martelli and Kristina Garalyté (dir.), South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 22 | 2019, “Student Politics in South Asia” [Online], Online since 15 December 2019, connection on 24 March 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/5852; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/samaj. 5852 This text was automatically generated on 24 March 2021. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Generational Communities: Student Activism and the Politics of Becoming in South Asia Jean-Thomas Martelli and Kristina Garalytė Student Politics in British India and Beyond: The Rise and Fragmentation of the All India Student Federation (AISF), 1936–1950 Tom Wilkinson A Campus in Context: East Pakistan’s “Mass Upsurge” at Local, Regional, and International Scales Samantha Christiansen Crisis of the “Nehruvian Consensus” or Pluralization of Indian Politics? Aligarh Muslim University and the Demand for Minority Status Laurence Gautier Patronage, Populism, and Protest: Student Politics in Pakistani Punjab Hassan Javid The Spillovers of Competition: Value-based Activism and Political Cross-fertilization in an Indian Campus Jean-Thomas Martelli Regional Charisma: The Making of a Student Leader in a Himalayan Hill Town Leah Koskimaki Performing the Party. National Holiday Events and Politics at a Public University Campus in Bangladesh Mascha Schulz Symbolic Boundaries and Moral Demands of Dalit Student Activism Kristina Garalytė How Campuses Mediate a Nationwide Upsurge against India’s Communalization. -

Telangana Issue After Holding Consultations with Leaders from Telangana, Rayalaseema and Coastal Andhra Regions for Over Two Months

Telangana What is Telangana? Telangana refers broadly to the parts of the state that formed the erstwhile Hyderabad state. Telangana is a region in the present state of Andhra Pradesh, India and formerly was part of Hyderabad state which was ruled by Nizam. It is bordered with the states of Maharashtra on the north and north-west, Karnataka on the west, Chattisgarh on the north-east and Orissa to the east. Andhra Pradesh State has three main cultural regions of which Telengana is one part and others include Coastal Andhra region on the east and Rayalaseema region on the south. The Telangana region has an area of 114,840 square kilometres (44,340 sq mi), and a population of 35,286,757 (2011 census) which is 41.6% of Andhra Pradesh state population. The Telangana region comprise of 10 districts: Adilabad, Hyderabad, Khammam, Karimnagar, Mahbubnagar, Medak, Nalgonda, Nizamabad, Rangareddy, and Warangal. The Musi River, Krishna and Godavari rivers flow through the region from west to east. Historical Perspective The ruler of India’s largest princely state, Mir Osman Ali Khan, the seventh Nizam of Hyderabad, was not willing to acede either to India or Pakistan in 1947. Then the Telangana Rebellion started, which was a peasant revolt which was later supported by the Communists. It took place in the former princely state of Hyderabad between 1946 and 1951. This was led by the Communist Party of India. The revolt began in the Nalgonda district and quickly spread to the Warangal and Bidar districts. Peasant farmers and labourers revolted against the local feudal landlords (jagirdars and deshmukhs) and later against the Osman Ali Khan, Asif Jah VII. -

The State, Democracy and Social Movements

The Dynamics of Conflict and Peace in Contemporary South Asia This book engages with the concept, true value, and function of democracy in South Asia against the background of real social conditions for the promotion of peaceful development in the region. In the book, the issue of peaceful social development is defined as the con- ditions under which the maintenance of social order and social development is achieved – not by violent compulsion but through the negotiation of intentions or interests among members of society. The book assesses the issue of peaceful social development and demonstrates that the maintenance of such conditions for long periods is a necessary requirement for the political, economic, and cultural development of a society and state. Chapters argue that, through the post-colo- nial historical trajectory of South Asia, it has become commonly understood that democracy is the better, if not the best, political system and value for that purpose. Additionally, the book claims that, while democratization and the deepening of democracy have been broadly discussed in the region, the peace that democracy is supposed to promote has been in serious danger, especially in the 21st century. A timely survey and re-evaluation of democracy and peaceful development in South Asia, this book will be of interest to academics in the field of South Asian Studies, Peace and Conflict Studies and Asian Politics and Security. Minoru Mio is a professor and the director of the Department of Globalization and Humanities at the National Museum of Ethnology, Japan. He is one of the series editors of the Routledge New Horizons in South Asian Studies and has co-edited Cities in South Asia (with Crispin Bates, 2015), Human and International Security in India (with Crispin Bates and Akio Tanabe, 2015) and Rethinking Social Exclusion in India (with Abhijit Dasgupta, 2017), also pub- lished by Routledge. -

Operation Polo - Hyderabad's Accession to India

Operation Polo - Hyderabad's accession to India Description: History, as we know, is told by the winning side, in the way they'd choose to. During Indian independence, the military action Operation Polo annexed the princely state of Hyderabad to India, against the communists and the Nizam rule. This part of history is often not spoken about as much as we speak of the freedom movement or the partition. Yunus Lasania, in his two-part episode on Operation Polo, tells the story of the Hyderabad rebellion through the people who lived through that time. In this episode, Burgula Narsing Rao, the nephew of the first chief minister of Hyderabad state before the creation of Joint Andhra Pradesh Burgula Ramakrishna Rao shares his memories and view of the Hyderabad rebellion during the last phase of Nizam's rule. Hello everyone! This episode is going to be very special. All the episodes that we will release this month will be important, as they relate with one part of Hyderabad’s history, which is suppressed since independence. In 2017, India celebrated 70 years of its independence. Funnily, the independence day back in 1947 didn’t mean anything to Hyderabad. Hyderabad was a princely state until 1948. It comprised parts of Maharashtra, Karnataka and Telangana, had 16 districts ( 8 in Telangana and 8 in Maharashtra). The present-day Andhra and Rayalaseema areas were with the British. During/after 15 August 1947, most princely states Joined the Indian union, but, Hyderabad was one among the handful that refused to join. The state of Hyderabad was ruled by the last Nizam- Mir Osman Ali Khan. -

Left Front Government in West Bengal (1971-1982) (PP93)

People, Politics and Protests VIII LEFT FRONT GOVERNMENT IN WEST BENGAL (1971-1982) Considerations on “Passive Revolution” & the Question of Caste in Bengal Politics Atig Ghosh 2017 LEFT FRONT GOVERNMENT IN WEST BENGAL (1971-1982) Considerations on “Passive Revolution” & the Question of Caste in Bengal Politics ∗ Atig Ghosh The Left Front was set up as the repressive climate of the Emergency was relaxed in January 1977. The six founding parties of the Left Front, i.e. the Communist Party of India (Marxist) or the CPI(M), the All India Forward Bloc (AIFB), the Revolutionary Socialist Party (RSP), the Marxist Forward Bloc (MFB), the Revolutionary Communist Party of India (RCPI) and the Biplabi Bangla Congress (BBC), articulated a common programme. This Left Front contested the Lok Sabha election in an electoral understanding together with the Janata Party and won most of the seats it contested. Ahead of the subsequent June 1977 West Bengal Legislative Assembly elections, seat- sharing talks between the Left Front and the Janata Party broke down. The Left Front had offered the Janata Party 56 per cent of the seats and the post as Chief Minister to JP leader Prafulla Chandra Sen, but JP insisted on 70 per cent of the seats. The Left Front thus opted to contest the elections on its own. The seat-sharing within the Left Front was based on the “Promode Formula”, named after the CPI(M) State Committee Secretary Promode Das Gupta. Under the Promode Formula the party with the highest share of votes in a constituency would continue to field candidates there, under its own election symbol and manifesto. -

A Perspective on Bhimireddy Narsimha Reddy's

Vol.2 No. 3 April 2018 E-ISSN: 2456-5571 A PERSPECTIVE ON BHIMIREDDY NARSIMHA REDDY’S ROLE IN TELANGANA ARMED STRUGGLE (1946-51) Dr. Gugulothu Ravi Lecturer, Department of History, Acharya Degree College, Warangal, Telangana, India Abstract Comrade Bhimireddy Narsimha Reddy was a freedom fighter and a leader of the Telangana Rebellion, fighting for the liberation of the Telangana region of Hyderabad State from the oppressive rule of the Nizam. He belonged to Suryapet district of today's Telangana. B.N.Reddy, as he was known, fought the Razakars during the Nizam’s rule for six years by being underground. He escaped 10 attempts on his life, prominent among them being an attack against him, his wife and infant son by the Razakars near Mahbubabad in Warangal district. Narsimha Reddy broke the army cordon while exchanging fire and escaped. He also carried out struggles against feudal oppression and bonded labour. Renowned across Telangana with his simple name of BN, he is none other than Bhimireddy Narsimha Reddy. Those were the days during which the poor people of Telangana suffered inexplicable exploitation at the hand of the Landlords and toiled as slaves without an iota of freedom He thought that socialism was the ultimate system for the safety of mankind. With the entry into armed struggle he fought against the Nizam’s rule and in a free society he aspired to provide food, shelter, employment for the poor people of Telangana. Keywords: Bhimireddy Narsimha Reddy’s role in Telangana Armed Struggle Introduction atrocities of the Nizam and need for a struggle against his Telangana Armed Struggle was a historical and a tyranny. -

Swap an Das' Gupta Local Politics

SWAP AN DAS' GUPTA LOCAL POLITICS IN BENGAL; MIDNAPUR DISTRICT 1907-1934 Theses submitted in fulfillment of the Doctor of Philosophy degree, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 1980, ProQuest Number: 11015890 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11015890 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This thesis studies the development and social character of Indian nationalism in the Midnapur district of Bengal* It begins by showing the Government of Bengal in 1907 in a deepening political crisis. The structural imbalances caused by the policy of active intervention in the localities could not be offset by the ’paternalistic* and personalised district administration. In Midnapur, the situation was compounded by the inability of government to secure its traditional political base based on zamindars. Real power in the countryside lay in the hands of petty landlords and intermediaries who consolidated their hold in the economic environment of growing commercialisation in agriculture. This was reinforced by a caste movement of the Mahishyas which injected the district with its own version of 'peasant-pride'.